Part 1

Popular recreations are part and parcel of the social fabric of communities through history. Harrier running stems in part from this culture. What follows is the context which delivers us to the mid to late 1880s when sport, in all its forms, became organised and codified. The new Harriers clubs of 1885-86 (only occasionally known as ‘Athletic Clubs’) are part of this sporting boom.

There has always been some form of running ‘culture’ both as part of popular recreation as well as a more functional form of societal service. One of the earliest descriptions we have is of a race between the running footmen of feudal lords and also of a race in the early years of the nineteenth century at Carnwath (The Red Hose Race) which has its roots of existence going back to 1456. With Fairs and Festivals as part of rural life of Scotland, many of the festivities were the only sources of release from everyday life and recreations of various sorts including foot races featured. There were however various ‘gatekeepers’ to enjoyment, from feudal lords to the Church. Thus, the journey of leisure time activities was often regulated and defined over many centuries as to what was acceptable and what was not. By the time we get to the nineteenth century influences were changing yet again. The context from which modern day Harrier club and athletic activity emerged was subject to a number of important factors which shaped the way the clubs emerging in the mid 1880s conducted their affairs. In amongst what follows may be some mongrel myths but bear with it and you’ll emerge with an insight into these new clubs.

The social and political changes of the nineteenth century played significant roles on popular recreations. There were of course some sports that we would recognise such as golf, the beginnings of cricket, horse racing, hunting ‘sports’ and the games and activities associated with village celebrations around the natural rhythm of countryside life. However, with rapid urbanisation and industrialisation, recreation also adjusted to the new and emergent stratifications in society. A ‘romantic view’ of the countryside was emerging as part of a longing for a way of life changed, thus shifting the way in which we not only viewed the countryside, but also engaged with it. Thus, going out into the countryside was an important antidote to the new, challenging city conditions and new forms of engagement in countryside activities emerged. The ‘view’ of the countryside changed considerably by the mid nineteenth century with organisations such as the church actively taking children out to the countryside and seaside from cities.

By the early nineteenth century betting and wagering on sporting activities became immensely and overtly popular as were the new and often inventive activities on which one could wager and place a bet. Pedestrianism was part of this as a new form of physical ‘challenge’ and from the mid to late eighteenth century into the nineteenth century, ‘Peds’ (most famously perhaps Capt. Barclay Allardyce) became household names bringing physical recreations such as running into the popular sphere. At the same time, ideas of nationhood and ‘patriotic’ games were much to the fore mainly as a popular narrative by such as Sir Walter Scott whose involvement in the visit of King George IV to Edinburgh in 1822 set loose a new notion of traditional Scottish sports and pastimes and was especially important in reinventing a new narrative of the countryside and engagement with it. Scott was one of the Edinburgh Six Foot Club whose aim it was to celebrate ancient sports and pastimes, and their activities in the 1820s and 30s listed ‘steeplechasing’ which, in essence, was a cross country race. The St Ronans Border Games of 1829 also listed a ‘steeplechase’ as did a number of other local Games. Cross border influences may also be at work here as the north of England had a rich heritage of local Games not least in the Lake District.

However, not all agencies saw popular recreations as a ‘good thing’. As cities grew at ever faster rates, the great fear of city fathers and the great and good of society was that the devil may make work for the idle hands of the ordinary workers and so recreation was made ‘rational’ with the intention of ‘improving’ the life of the ordinary (mainly) man. This idea of ‘Rational Recreation’ was to strongly influence the new Harriers clubs of the mid 1880s. Popular sports and pastimes were rationalised with an ideology of usefulness while new forms emerged and became popular. The new interest in physical forms of popular and acceptable recreations saw a burgeoning of various tracts on health, fitness and new gymnasiums became popular as did swimming baths. The press also started reporting on physical recreation activities thus bringing them to a larger audience (eg. the Scottish Athletic Journal had a circulation of 15,000 plus at its height).

By the mid 1880s the need to promote recreation as ‘rational’ had changed to the need to organise it. Railways were beginning to open up opportunities for movement, and within cities transport was becoming organised, thus meetings, matches and contests between others was opened up.

As is so often the case however, some of what developed was accidental. In 1850 students at Exeter College, Oxford despairing of the horses available to them to ride over the adjacent countryside hit upon the idea of replicating the idea of a ‘chase but on foot (called a College Grind). Preceding this was the Crick run of Rugby School and the various runs of other Public Schools. Thus modern cross country running comes from various forms and influences and by the mid 1880s these young men were firmly in the grip of the new ethos of the muscular Christian that ‘manliness was next to godliness’ and so physical recreation had become a necessary marker of this manliness. Not only athletic contests but other sports emerged and by the 1860s national organisations had been formed (The Football Association, 1863; Amateur Swimming Association, 1869; Amateur Athletic Club, 1866 became the Amateur Athletic Association in 1880 and The Amateur Rowing Association in 1882 from the Metropolitan Rowing Club 1879).

Scotland was part and parcel of this new vogue for rational and acceptable physical activities. The diffusion of these activities was partly (although not exclusively) through the universities and public schools. Early athletic contests existed between the universities of Edinburgh and Dublin and as many students became school masters, sporting forms were diffused and popularised. By the early 1880s swimming, rowing, gymnastics, cycling, rugby, cricket and football were all firmly established as acceptable forms of manly physical activity (Queens Park FC the earliest club formed in 1867). The formation of the new Harriers clubs emerging from 1885 onwards owe much if not all their existence to the men involved in those other sports forming not only Harriers sections, but new Harriers Clubs. These new clubs in character and conduct epitomised the idea of the gentlemen’s sporting club as part and parcel of a marker of respectability. To ‘belong’ was much valued and set you apart in society generally and was part of ‘getting on’ which was an emerging hallmark of Scottish civil society.

This notion of the Victorian men’s club is an important factor in the emergence of the new Harriers Clubs. This period epitomised the nature of belonging to a club as a marker of getting on and belonging in civil society. Numerous male clubs were already in existence from the earlier part of the century and new ones were always springing up, some with dubious and obscure provenance. Just some examples of the, at times, highly improbable contexts in which clubs were formed are: The Hodge Podge Club (Tobacco lords), Pig Club (Sugar), What you Please Club (Theatrical) and the wonderfully named The Wet Radical Wednesday of the West Club (Waterloo Radical Movement). Sports clubs were relatively late into this framework of male homosocial activity but as will be seen in Part 2 of this article, they became no less important not only for members but also in recruiting patrons. The new Harriers clubs also embraced the norms and functions of other male clubs with the acquisition of ‘Rooms’ and associated male club activities (developed in a further article). One of the reasons that Harriers clubs were later in their formation was perhaps to do with the fact that by their very nature they visited various parts of the country for their activity thus one central place of ‘home’ such as other sports was more difficult to reconcile. They did however overcome this factor by adopting hotels and key venues in which to change in various parts of the country that they visited for runs as well as (usually) a hotel for main meetings.

By the 1880s, the scene was set for the emergence of Harriers clubs as both sporting and male social clubs in their own right.

Part 2

Being the ‘oldest’ or being the ‘first’ in anything always brings with it a status. Being the first Harriers club is no different. However, the sporting landscape of Scotland had been changing rapidly in the 20 years preceding the first Harriers clubs. It is important to keep in mind not only the ‘new’ clubs in gymnastics, swimming, cycling and the team sports but also Scotland’s rich tradition of local Games such as the various Highland Games. Influences from abroad were also part and parcel of the formation of the Harrier clubs. In 1883 the USA held its first NYAC cross country Championships and Ireland had also held its first cross-country championship by 1881 with the inaugural French cross country championship in 1889 (Canada had a governing body by 1884 and also New Zealand by 1888). This diffusion was undoubtably led by emigration. Our next door neighbours in England were ahead by about a decade. Influences therefore were many and varied including changing societal attitudes and values in relation to acceptable activities.

The prevailing view that Clydesdale Harriers was the first Harriers club (formed in 1885) is widely accepted. However, this may not be the case. We know of the presence of a club preceding this called Towerhill AC (AC at this time denoted a club that had a broad involvement in more than one sporting form). We also know of ‘sections’ of existing sports clubs in 1885 devoted to Harrier running such as that of the Lanarkshire Bicycle Club and Langside Bicycle Club. It is probably accurate to accord Clydesdale Harriers the position of being the first bespoke Harriers Club that also managed to stay in existence (others came and went). Clydesdale’s club history records the club being formed of men from football, rowing, cycling and cricket clubs (indeed the history records Clydesdale beating Celtic FC in a cup tie in 1889).

Prior to 1885 the central athletic activity recorded is mainly around other sporting clubs holding athletic sports in the summer months as a means of making money. These were given the nomenclature of ‘Sports holding clubs’ and they often vied with each other in attracting the leading athletes of the day which subsequently boosted gate money. While most were football clubs some gymnastic, rugby, cricket and cycling clubs also held sports days. Some of the better known sports days were that of Queens Park FC, Abercorn FC, Vale of Leven FC and Rangers FC. In the face of creeping professionalism, some clubs in the east of Scotland made a move to set up a governing body to establish rules and in February 1883, the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association was formed.

The new SAAAs however was almost exclusively run by men from other sports, mainly rugby, football and the universities and the setting up of the governing body met with almost instant disapproval from sports clubs in the west of Scotland. It was clear that there was an emerging sporting ‘aristocracy’ vying with themselves for control of a sporting activity that gave influence and not a little financial support for other sports clubs through Sports Days. Athletics (in the sense of both track and field and cross-country running) became a battleground of control and resistance for some years to come. The story of this is worth developing as a separate piece. It is in part therefore, due to a number of catalysts, that we find ourselves by 1885 with the formation of new clubs. Three clubs now take centre stage. Clydesdale Harriers, Edinburgh Harriers and The West of Scotland Harriers. Clydesdale Harriers were formed on Monday 4th May, 1885; Edinburgh Harriers on 30th September, 1885 and the West of Scotland Harriers on 14th September, 1886. These clubs almost certainly recruited men who had experience of Harrier running as it would be unlikely to join a club without such prior knowledge and experience of the activity. This suggests that many of the clubs that these men were already in membership of, either had Harriers sections or had put on runs perhaps as part of training or in place of activities in winter months

Clydesdale Harriers

At its meeting on 4th May, 1885 Allan Kirkwood was elected President, A.M. Campbell as Treasurer and Alex McNab as secretary. Given that it was now the summer months they set about organising a track meeting on the south side of Glasgow. The club were formed by the partial influence of the McNeill brothers of Glasgow Rangers FC and their choice of name may in some way be connected with an area of Lanarkshire where one of the McNeill brothers lived for a period of time. The club also had connections with Partick Thistle FC. Members of Linside Rowing Club were also members as well as members of the Victoria and Caledonian Bicycle Club of Paisley and the club developed extensive links with other football clubs around the west of Scotland. Clydesdale Harriers carried the flag for Harrier activity and athletics generally for the next year which saw the sport develop its own marque mainly through cross-country running, as this form of activity was sufficiently set apart from those members of the SAAAs such that it was relatively non-threatening. Clydesdale was therefore able to set about establishing the boundaries of the sport and its social structures. It also had to deal with betting rings such as the ‘Co-partnery’ but the club in some respects was also a function of the inactivity of the new SAAAs.

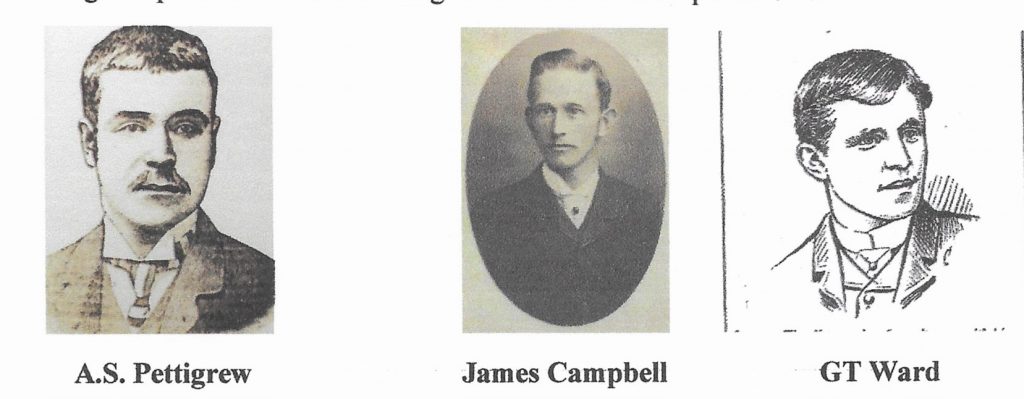

Clydesdale’s membership initially was wide and varied and perhaps just three examples serves the purpose of illustrating the draw Clydesdale had in attracting members from other sports wishing to ‘specialise’ or add running to their list of accomplishments.

A former pupil of Glasgow High School, Pettigrew played football while at school. He also sailed lugsail boats and swam (member of Queen’s Amateur Swimming Club). An initial member of Clydesdale Harriers he was also a member of Clyde Amateur Rowing Club and excelled both as a sculler and single oarsman. James ‘Teuch’ Campbell won the second Scottish cross-country championship in 1887 and had a successful career as a doctor in Helensburgh. George T Ward is best known as an excellent sprinter. A founder member of the club in 1885, he took part in Clydesdale’s first track meeting in May 1885. He and Tom Blair of Queens Park FC were, more famously, involved in 1887 in challenge matches over 220 and 440 yards.

Clydesdale duly set about arranging track events for the summer while preparing for a winter of cross-country running and successfully put on a number of meetings, which not only attracted attention, but also new members. It also sent the first signal to the new SAAAs that there was now a club whose central focus was both track and field as well as cross-country. However, from the start there was to be controversy in relation to the influence of betting from book makers at meetings, arising in part not just as a threat to the amateur ideal, but also linked to the handicapping of athletes. This was a problem that was to affect clubs and the sport for some years to come.

Edinburgh Harriers

This club was a distinct mix of interested parties. Formed on 30th September, 1885 at the Richmond Hotel in Edinburgh, the meeting was conceived by St George’s Football Club who wished to form a harriers section of the club. However, one David Scott Duncan (later to be thought of as the ‘Father of Scottish Athletics’) had convened a meeting the evening before between friends and colleagues from the university in Edinburgh where he had been a student (law) and from Edinburgh schools. He wished to form not a section but a separate club in Edinburgh given over to Harrier running. While no decision was taken at the meeting of the 29th, he attended the meeting on the 30th and spoke eloquently about the need to ‘form one (club) on a more liberal basis’ rather than as a section of another club. The motion was carried and Edinburgh Harriers was formed. They wasted little time.

Their first run was from the Harp Hotel in Corstorphine on 17th October, 1885 over 6 miles and is the first run of any Harrier club of the ‘modern era’. Walter Gabriel a well known Edinburgh University member was pace along with David Scott Duncan as whip, and a further 14 runners completed the course including JN Bow who was to become President after Walter Gabriel. They subsequently used a number of venues around Edinburgh as bases for running such as the Volunteer Arms, Morningside; Mrs Crosbie’s Inn, Levenhall; Sheephead Inn, Duddingston and Justinlees Inn, Eskbank. By 1887 the club had a membership of just over 300 in a matter of two years.

The initial membership of the club spanning the inaugural meeting and their first run included RH Morrison, TED Ritchie, DS Duncan, W Rodger, J Caw, J Heron, WA McLaren, JH Allen, WH Wilson, WP Grant, JG Grant, G Beattie, Webster Brown, R Paton, WP Arnot and JC Clarkson, JN Bow, JHA Laing, J Luke, Walter Gabriel, AM Luke, J Meek, EJ Keith, FW White, J Macrae, G Weir, JWL Beck, W Williamson and J Menzies.

The influence of David Scott Duncan would have been significant. He was a singularly well connected man. He was appointed secretary of the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association just the year before in 1885 while still in his mid twenties. By this time he had also made his mark as a scholar at Royal High School (winning the India Prize) and at the University of Edinburgh studying law. He would go on to initiate an athletic contest with Ireland; become a scratch golfer (Captain of the Royal Musselburgh Club); run in over 300 races winning over 150 prizes and also become editor of the Golfing Annual and also become the correspondent for ‘The Field’ in Scotland. He was a man of both influence and charm who had the abilty to ‘take people with him’ in discussions and arguments, a skill that would become much needed of the next few years as the cross-country running wrestled with various assaults on its path to an autonomous sport.

The occupational status of other Edinburgh Harriers was interesting. The limited amount of research so far indicates that initial membership included 2 Writers to the Signet (Bow and Duncan) with significant numbers drawn from former pupils of Royal High School, Edinburgh and the University. However by 1887 with membership at some 300, it is clear that the membership of Edinburgh attracted men of some social position. The issue of the social status of members of Harriers clubs is the subject of another article.

Edinburgh Harriers and Clydesdale Harriers held the first inter-club run in February 1886 at Govan with the first Cross-country Championships being held shortly after in March (AP Findlay of Clydesdale Harriers won from DS Duncan of Edinburgh Harriers but Edinburgh winning the team race).

There then followed a brief pause in the formation of clubs. In reviewing the sources the issue of ‘local politics’, control, suspect handicapping at sports meetings and social mobility all played their part. One of the first inklings that all was not well with athletics more broadly in the first year comes from an observation in the Scottish Athletic Journal of August 5th, 1885 some 3 months after the formation of Clydesdale Harriers. The author, signing himself as ‘Utilitarian’ observes that ‘Clydesdale harriers will soon tire of private runs. Why should not the Queens Park form a harrier section to the club for non-football playing members?’ He then goes on to state that ‘The men of the Clydesdale burn to meet foemen worthy of their steel, and none are to be found. It is a capital sport, and will soon become popular. Moreover, it is splendid winter training.’ It is clear that the two main sporting newspapers of the day took opposing sides. The ‘Scottish Umpire’ was strongly supportive of Clydesdale Harriers while the ‘Scottish Athletic Journal’ promoted the idea of setting up of more harriers clubs. Why these relative positions should have been adopted is not clear except that over the next few weeks and months a war of words broke out in relation to a new club culminating in the summer on 1886, when it became clear that there had been many approaches and discussions in relation to setting up another club. This was duly announced in the Scottish Athletic Journal in August and September of 1886.

In September 1886, the West of Scotland Harriers were formed. However, other events were shaping the landscape of track athletics which in part led to the formation of the new club. There was a growing number of Sports Days put on by clubs of other sports by 1885 and handicapping became a source of contention and at times outright hostility. There existed a group known as the ‘Co-Partnery Ring’ which although shadowy is thought to have been an unholy alliance between handicappers of the day and those involved in betting and gambling thus leading to races being ‘fixed’. There were numerous attempts to solve this, but due to the often obscure membership of the Co Partnery, little progress was made. Accusation followed counter accusation and the SAAAs also appeared powerless to deal with it. The result was that a number of individuals took matters into their own hands. Unfortunately for Clydesdale Harriers, being the only ‘athletics’ club many of their members were at the sharp end of the ensuing civil war. Some officials (of which a Mr Tait was one) tried to ensure the status quo held.

The athletes themselves tired of the unfair handicapping system they were forced to endure and in the period of the winter cross-country season of October 1885 and March 1886 there was clearly a move to break the hold that some viewed the existing clubs and organisations to have on the sport. Part of this early debate also centred around the objective of Clydesdale Harriers to support the growth of ‘sections’ of the club around the west of Scotland. By 1886 they were successful in promoting the sport through these means although in the first year of its existence it had only managed to take its club runs to a small number of limited venues as well of course as hosting the first inter-club with Edinburgh Harriers. However it was clear that Clydesdale Harriers had aspirations and viewed the growing discontent and the prospect of new clubs with some concern. Newspaper sources then pick up what was to become a recurrent theme as to the motives and background of individuals who were, by summer 1886, openly talking of starting a new harriers club. Those involved in the early discussions to set up this new club were seen as ‘elite’ and snobbish. The gauntlet was laid down on September 7th, 1886 with a circular reprinted in the Scottish Athletic Journal of an invitation to all athletic and football clubs in the west of Scotland to form a Harriers club in Glasgow. The response in the The Scottish Umpire was immediate. It condemned the circular as ‘conspicuous for its ignorance or disregard for contemporary history’ It went on to say that the reason for promoting another Harriers club in Glasgow would not be accepted by the general body of western athletes. They viewed the new club as ‘opposition’ and as an ‘unfriendly rival’. With gloves off, the new harriers club was formed a week later.

The West of Scotland Harriers

At a meeting at the Langholm Hotel on 14th September, 1886 the West of Scotland Harriers was formed. From the outset, the signatories to the original circular and those present at the meeting included some big hitters on the sporting landscape. The original circular was signed by AS Pettigew clearly disaffected by Clydesdale Harriers and wishing to move clubs; footballer AD Finlayson of Queens Park FC, cyclist CC Calder of Royal Scottish Bicycle Club, cricketer AJ Young of Dennistoun Cricket Club and rower WM Walker of Clydesdale Amateur Rowing Club.

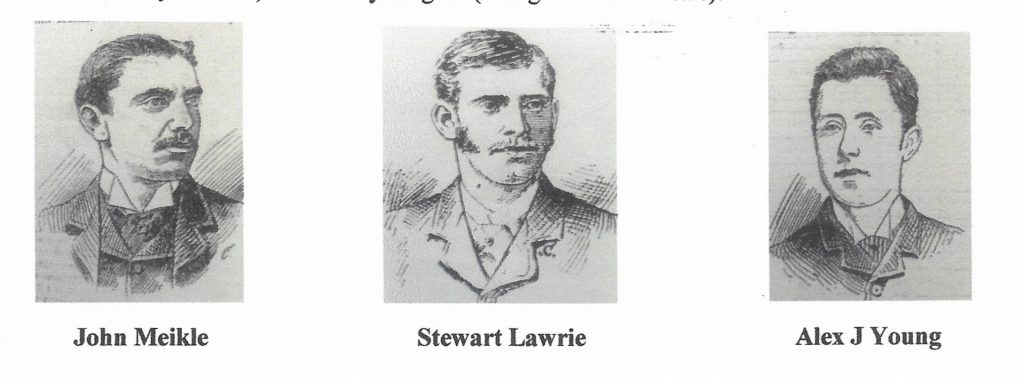

At the meeting of 14th there were reputedly 50 gentlemen present. Although MP Fraser of Glasgow University Athletic Club had been asked to chair, it was CC Calder from the Royal Scottish Bicycle Club that took the chair. Both MP Fraser and DS Duncan had sent letters of support which were read out. Also present was a Mr Lawson from Clydesdale Harriers but withdrew from the meeting at the early stages. The meeting went well. John Meikle of Bellahouston Bicycle Club proposed the motion to form a Harriers club for the west of Scotland; WH Walker of Clydesdale Rowing club seconded the motion and it was carried by acclamation. The West of Scotland Harriers became the third club to be formed. T Skinner proposed the name the West of Scotland Harriers Club.

The office bearers make interesting reading. Elected to President of the club was Stewart Lawrie of Queens Park FC and one of the dynasty of Lawrie brothers who played for the club. Stewart Lawrie was to become one the key figures in Scottish sport also becoming president of Queens Park FC (having joined in August, 1880 aged 21) as well as president of the Scottish Gymnastic Association, Scottish Cross Country Association and the SAAAs. Lawrie had been a member of Langside Bicycle Club and may well have been a member of their ‘Harriers section’ prior to the formation of any bespoke Harrier club. T Skinner (Western Bicycle Club) was elected as Vice President, treasurer was AJ Young (Dennistoun Cricket Club), John Meikle (Bellahouston Bicycle club) as Secretary and WM Walker (Clydesdale Amateur Rowing Club) was elected club captain. Vice-Captain was JD Finlayson (Queens Park FC) and the committee consisted of DC Brown (Queens Park FC), GW Brown (SGBC), AS Pettigrew (Clyde Amateur Rowing Club), CC Calder (Royal Scottish Bicycle Club) and AC Symington (Glasgow Academicals).

Support was received from cycling clubs, rowing clubs, the 1st Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer Athletic Club and Glasgow University Athletic Club as well as various rugby clubs such as Glasgow Academicals, West of Scotland, Kelvinside AC, Queens Park FC and Battlefield FC. Membership was drawn from a wide range of social groupings and interests including not only the above but also former pupil clubs of Glasgow schools such as Glasgow High School and even one member from Airedale Harriers in Yorkshire, WH Higgins.

West of Scotland Harriers 1886

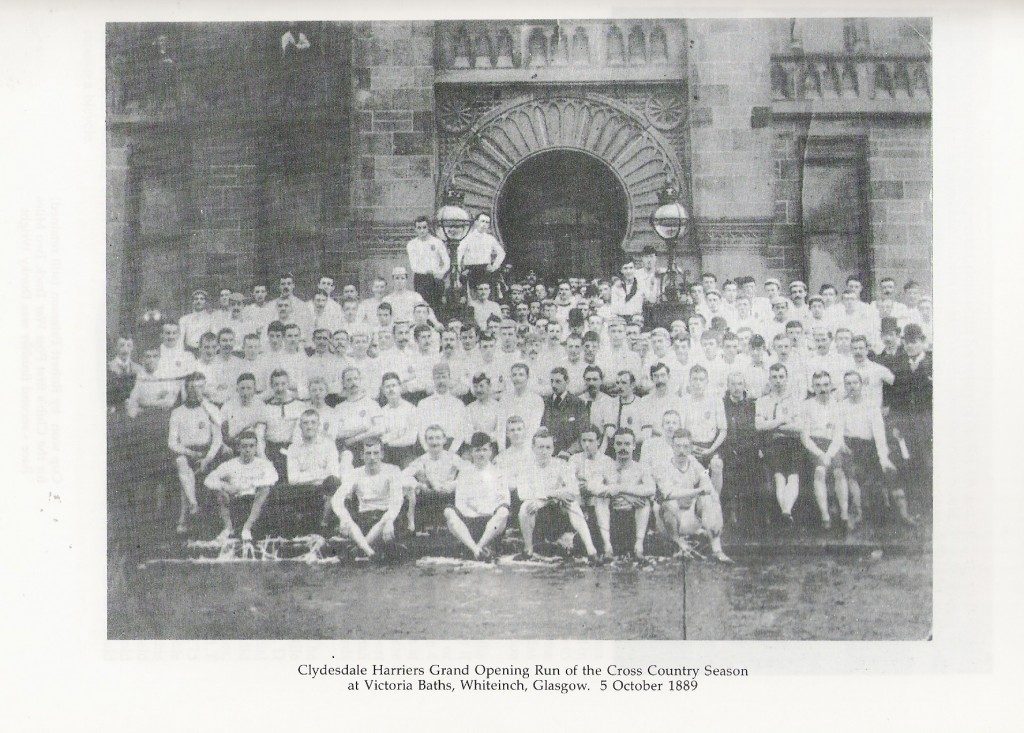

This is believed to be the oldest club photograph of any of the three clubs. Long sleeved jerseys were obligatory (wool) and clearly visible are the trail makers. The footwear is varied but of course they would be wearing what they would normally wear for the previous main sport. Clearly visible is Stewart Lawrie (5th from the left back row) and DC Brown (3rd from the left back row). Also clearly visible are the horizontal black and white stripes of a Queens Park FC strip. It is not known what function the dog went on to serve!

The scene was now set for a fuller cross country season for 1886/87.

Conclusion

It is always difficult to infer from sources that are scarce but the job of anybody recounting history is to deal with the facts when they are clear and to ‘suggest’ when they are less clear. Nearly all of the above has been gleaned from club histories where they exist and from contemporary newspaper sources who have their own camps that they support and indeed contributors who may be partial. Further work is needed on those years that preceded 1885 in order to establish just how young men came to enthuse about Harrier or cross-country running. It clearly was a sport that had been sampled but with whom and when and how often? A deeper understanding of both Edinburgh Harriers and the West of Scotland Harriers is also needed since neither have been researched properly unlike Clydesdale Harriers whose club history was undertaken by Brian McAusland. Biographies are also needed of those ‘movers and shakers’ who guided, cajoled and drove the sport in the various directions they thought appropriate. While some attempt has been made to fill in some biographical information in this short initial history, the real understanding of what happened and why often lies with the personal ambitions and trajectories of key individuals.

This short history of the beginning of Scottish Athletics and their clubs also needs to be understood in the context of governance and the ensuing battle for control. Over the following years from 1885 there was some 7 attempts to exercise governance over organisations, clubs and individuals and this will be the subject of a further piece. However, no history of the initial days of the sport would be complete without the more human and ‘ordinary’ face of the sport. There is ample evidence to suggest that these new Harriers clubs were havens for the personal and social aspirations of their members. Gentlemen’s clubs were still part of social mobility for aspiring young men. The enthusiasm that the original clubs also set about in gathering Patrons, is testament to the way they viewed themselves and their position in Scottish sport as well as setting down a marker as to the type of member it wished to attract. ‘Belonging’ was everything in Victorian male civil society! This will be subject of a further piece of work showing the homosocial, liminal and at times disgraceful behaviour of club members.

Further contributions and corrections to this article are more than welcome.