Ralph Erskine

Ralph Erskine is not a name well-known to athletics supporters whether the casual observer or to the aficionado. The few who do know have only a scanty knowledge of the man and his career. He was a member of Clydesdale Harriers and won medals in Scottish championships as well as running in the Triangular International against Ireland and England. He was also part of a family which hadmore than its share of tragedy linked to the 1914-18 war. He is just one of the hundreds of young sportsmen who died during the First Great War, just one of dozens of Clydesdale Harriers who were sacrificed. The club had two joint secretaries when the war started, his brother Tom and Harold Servant, neither survived the conflict, nor did most of the club committee of the time. This is Ralph’s story.

Ralph Erskine was born on 10th March 1893 in Camlachie, Glasgow, the younger son of Captain James Erskine, Gordon Highlanders, and Janet (Jenny) Penman Barrie. His brother (Thomas Barrie Erskine) was three years older, his two sisters (Margaret and Agnes, known as Nancy) were respectively two and four years younger than Ralph. Margaret died of tubercular meningitis at eighteen months, when Ralph was three. When Ralph was just eight years old, in 1901, his mother Jenny died of consumption. That year the census return shows James and his two sons (11 and 8) living at Tollcross, Glasgow. The little sister was being looked after by an aunt, and she spent most of her childhood with an aunt and uncle in Wales. His father had been a founder member of Clydesdale Harriers when it was formed in 1885 and both boys would become very active members of the club in their turn. This was however only part of his sporting achievements and possibly not the greatest.

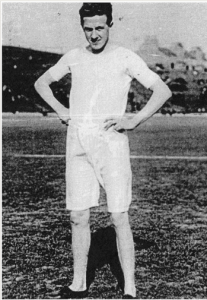

Ralph was educated at Allan Glen’s school, Glasgow, as was his brother. He was a gifted athlete and boxer, featherweight boxing champion of the world at age 17. Sporting success reported at the time included the Public Schools’ Boxing Championship of England in 1911, and the Feather-weight Amateur Championship of Scotland in 1912. Anent the former, the ‘Glasgow Herald’ of 5th June 1911 contained the following paragraph in its ‘Sports Miscellany’ column: “Professor G Ramsey, on hearing of Ralph Erskine’s success in the Public Schools’ boxing championships, sent the following congratulatory letter to Dr Kerr:- ‘I cannot tell you how pleased I am to see the old school in an important contest taking first place among the great public schools of England. I congratulate you with all my heart, knowing how you have cared for the physical as well as the intellectual side.”

He also won the European championship at Paris. In May 1911 Ralph sailed to New York for a fight for the (unofficial) Amateur World Featherweight Title. He fought at the famous National Sporting Club on 27th May 1911 and the following day the New York Times reported: “The star of the lot was Ralph Erskine, the 17 year old boy who fights in the 125 pound class. He fought Alfred Roffe, the Canadian champion, and simply toyed with his opponent all through the three rounds. He had all the actions of an experienced performer and the speed of a Jem Driscoll”. He easily outpointed Roffe.” * (A famous featherweight champion from Cardiff who fought his way from poverty to the British Championship before dying of consumption at the age of 44.) The Harriers yearbook for 1911-12 reported “One of our youngest members, Ralph Erskine, has achieved great success in the Boxing World during the past season. Amongst his numerous victories may be mentioned those in the English Public Schools Championship, the Scottish Championship, the World’s Amateur Featherweight Championship at New York and the defeat of the French Champion in Paris.” Ralph returned from New York to Liverpool in 1911 on the SS Lusitania.

Once back home he gave several exhibition bouts – one being at the Rangers FC Sports on 5th August 1911 against his cousin, George Barrie. “It was much appreciated and proved an interesting variation to the proceedings.”

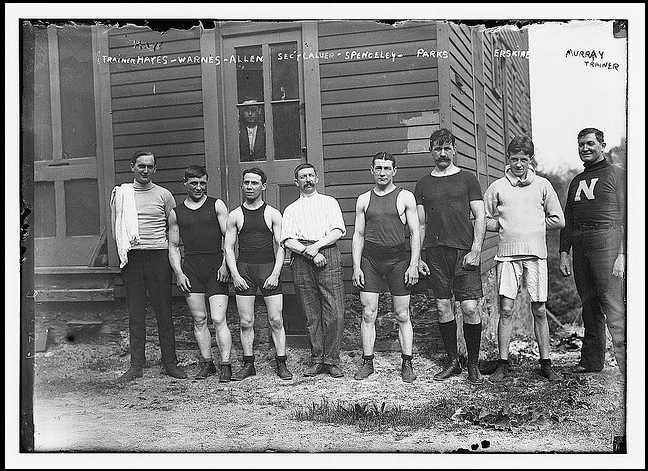

British boxers including R Erskine (2nd from right) with E T Calver, Secretary of the Amateur Boxing Association (ca.1910)

Back at home, he was a committee member in season 1911-12 but while brother Tom became joint secretary and member of the finance committee, Ralph left after only one season. While his brother won several prizes at club level and took part in open meetings, Ralph seemed to race less frequently but with more success. Slighter of build than his brother, he had been a more ‘natural’ athlete and distance runner at Allan Glen’s.

If we look at his preparations for the championships where he won his first SAAA medal, 1913, he does not seem to have raced much. In the Clydesdale Harriers Sports on 31st May at Ibrox, he ran in the second heat of the 880 yards and, although beaten by George Dallas of Maryhill, qualified for the final where he was unplaced. On 21st June 1913 the Inter University Sports were held at Aberdeen and Erskine was out in the quarter- and half-mile races. He finished second in both – in the 440 yards to N Gibson who won in 53.4 secs and in the 880 yards to R Thorp whose time was 2:04.5. Then it was the championship where he was second to DF McNicol at Celtic Park on 28th June. There were two heats for the championship and twelve men taking part with McNicol only taking the lead off the last bend and winning by about 10 yards in 2:04.8. The international was held in Ireland on 19th July and Erskine was unplaced..

His lead in to the Scottish championships in 1914 was an interesting progression – and featured more races and a different pattern from the previous year. Not noted as a long distance runner, nevertheless he turned out in a two miles team race at the Greenock Morton Sports on 23rd May at Cappielow. Then as he neared the championship he came down via the mile to his favoured distance of 880 yards. At the start of June he ran 2:12.2 in Glasgow University colours at Anniesland. Then the University Championships were held the week before the SAAA event – on 20th June 1914 – and Erskine was out in the half mile and mile. The preview of the event reported that he had run inside 2 minutes 12 1-5th. The report read: “Both the mile and half-mile were won by R Thorp (Edinburgh University). In the longer race, Ralph Erskine of Glasgow led for half distance, when JA Young, Edinburgh, went forward. At the bell Erskine was overtaken by the winner, who ran neck-and-neck with Young for 50 yards when the holder shot out and won by ten yards, the Glasgow man being a bad third. Erskine was seen to greater advantage in the half-mile, in which he was hardly a couple of yards behind Thorp at the tape.”

In the national championships, Erskine was second again, this time to clubmate Duncan McPhee in 1914 at Powderhall. He was only two yards behind the winner at the finish who won in 2:05.2 with George Dallas of Maryhill Harriers third. This of course earned him selection for the triangular international to be held at Hampden Park on 11th July. Erskine led this one early on but was soon overtaken and, the pace was clearly too much for him with the winning time being 2:00.2 and he was again out of the first three.

When war broke out in 1914 Erskine, a medical student at Glasgow University, was an athletics blue and had served as sports secretary and secretary of the athletics section. On a hiking holiday in Arran with his friend Charles Higgins when war broke out and they immediately headed back to Glasgow to join up. Ralph was given a Commission in the Royal Scots Fusiliers, and, having landed at Boulogne on 9th July 1915, he was promoted to Captain and after some heavy fighting in France, fought in the Battle of Loos (25 September – 18 October 1915).

In July 1915, not long after Ralph had landed on the continent, his brother, Captain T Barrie Erskine MC, Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, was killed in Flanders. Serving in the 1st Gordon Highlanders he was killed at Hooge.

In December 1915 Ralph relinquished the temporary rank of Captain, and joined the Royal Flying Corps, forerunner of the RAF (first spending some time with the Australian Forces Royal Flying Corps, probably for training). Given the nature of warfare on the Western Front, it is not difficult to imagine why men would seek to transfer into the Flying Corps. Many had experienced the misery and squalor of the trenches. Those who knew they would face danger as long as they were on the ground, preferred to face it in a corps which offered the promise of independence and glamour, as well as a degree of comfort unknown to the men in the trenches. Men who had already served in the ground forces reasoned that if they survived the day’s flying they would at least have the chance to sleep in a comfortable bed. Posters like the one below would have proved attractive to the young men.

Many of those who joined the squadrons on the Western Front had prior service. Many were recommended for admission by their commanding officers on no other ground than their good record as soldiers in the line. Many pilots were killed in accidents long before they could join a line squadron. Pilots who survived training were posted to operational squadrons where the thought of meeting the enemy in the sky was enough to give even the bravest men pause for thought. There was eight-months’ training before being sent to the front. The days when enemy airmen waved to each other on reconnaissance flights were long gone. Aircraft now carried machine-guns as standard equipment, and interrupter gears, developed in 1915, enabled pilots in single-seat fighters to fire straight ahead through their propellers.

By 1918 aircraft were being used in a variety of roles: some as fighters, others for reconnaissance or artillery spotting, and others for bombing operations inside enemy territory. The famous Sopwith Camel could reach 12,000 feet in 12 minutes, fully loaded with weapons and ammunition. Pilots and observers sat exposed to the elements in noisy open cockpits. Ralph Erskine served for a considerable time as an observer in France, where he was wounded, and mentioned in despatches.

On 9th March 1917, Captain Ralph Erskine RFC was married at St Columba’s Church of Scotland, Pont Street, by the Rev. J. C. Higgins, B.D., minister of Tarbolton, uncle of the bride, to Jane Lennox, only daughter of Mr and Mrs William Higgins, Glenafton, Church Road, Wimbledon.

Ralph and Lennie on their wedding day, March 1917

with James Erskine (left)

After getting his “wings” Ralph returned to France with 66 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps from 22nd September 1917 as a pilot. He was flying a Sopwith Camel, B6414.

Ralph was killed at the age of 25 when his aircraft was shot down in Northern Italy – the first British airman to fall there. “Force-landed in front line trenches near Flers. Aircraft destroyed by artillery fire.” According to information in a later family letter, he didn’t have a parachute. He was wounded in the leg, but died in captivity on 1 January 1918 and was buried at the British military cemetery in Tezze, near Venice. His former headmaster at Allan Glen’s spoke of Ralph as “a modest, kindly, courteous gentleman as finest quality as student, athlete and soldier, and probably the brightest spirit the school had ever known”.

Just two weeks after he was killed, on 16th January 1918, Ralph and Lennie’s son was born. He was baptised Ralph Barrie Erskine on 4th May at Trinity Presbyterian Church, Wimbledon by the minister, Dr Macgregor. Ralph junior was also killed at the age of 25 during WW2 at the battle of Longstop Hill, Tunisia.

Sopwith Camel

An obituary was printed Presbyterian Messenger (Local Supplement April 1918) as follows

Missing since the 1st January, 1918, now unofficially reported killed in air battle on that date, Ralph Erskine, captain, R.F.C., younger son of Captain James Erskine, Gordon Highlanders, and beloved husband of Lennie Higgins, Glenafton, Wimbledon. Captain Erskine, who was married to Miss Higgins little more than a year ago, had been for some weeks on the Italian front, and had highly distinguished himself on several occasions. After an engagement on New Year’s Day he was reported missing, and some weeks later news was received, through a neutral country, of his death. Captain Erskine was a man of splendid physique, one of the finest athletes perhaps in the whole Army, a complete master of aircraft, extraordinarily cool, resourceful, and courageous. His Major – himself killed since – bore the strongest testimony to his brilliant services. We can but think of him as true and faithful to duty to the last. The deepest sympathy is felt with his young widow and her little boy, with Mr and Mrs Higgins, and with Captain James Erskine, Gordon Highlanders, the fallen officer’s father, who has now lost both his sons and his son-in-law in the war.

Tezze British Cemetery, Italy (Ack. CWGC) Plot 6. Row C. Grave 16

Back in Glasgow, the Clydesdale Harriers had suspended their activities for the duration of the War and held their first post war meeting on 31st January, 1919, and present at the meeting and among the Honorary Presidents elected was Captain James Erskine.

That seems an appropriate place to stop. The information for the above came from

The Clydesdale Harriers Archive,

The Glasgow Herald’,

The University of Glasgow Story ( http://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk/ww1-browse/?start=20&max=20&o=&l=e )

the ‘Trinity Remembers’ website ( https://trinityremembers.wordpress.com/2014/06/23/ralph-erskine-1893-1918/ ),

Allan Glen’s Club Newsletter ( http://www.allanglens.com/images/newsletters/Mar2011.pdf )

the Erskine family/Lee family history ( https://leefamilyhistoryarchive.wordpress.com/category/erskine-family/

Clydesdale Harriers October 1913 – how many fought/died in the War?