CHAPTER XVII

WHAT IS THE BEST ATHLETIC AGE ?

YOU can be pretty safe when you say that this is one of those problems that defy a hard and fast solution. But in spite of that you can get as near to it as no matter if you take a careful survey of the principal factors.

On the surface it would appear that when a man is in the first flush of full physical development he must necessarily be at his best, so far as muscles, suppleness and energy go. In one sense that’s right enough, and it will explain why sprinters are undoubtedly at their prime in the earlier twenties. But having got so far you come to a point where there’s more in it than mere muscles and suppleness : mental equipment has to be taken into account as well, and with its aid some years can be added to the apparent summit period.

You see it’s like this : we must have been just physical animals for thousands of centuries before we developed brains to such an extent that they could be trusted to take entire command and oven over-rule instinct. Now that we’ve reached that stage we’ve lost most of our instinctive action, and intellect has to rule the roost instead. It does this to such purpose that we have already learnt how our minds can direct and enhance physical action ; can develop abilities to an even greater extent than any ” born athlete ” who fails to use his head to advantage. That will explain why, in athletics, the white man has always beaten the coloured man whose brains are not so advanced, except when he has taken his coloured rival in hand and trained him as he trains other whites. That gives you a. sound reason as to why the blacks should, at any

51

rate temporarily, beat the whites at sprinting, for they’re much less removed from atavism and savagery, and consequently have less (ground to make up. But they don’t make it up until the white has taught them just how to do it.

During an actual sprint intellect doesn’t get much of an innings because there isn’t time ; a fellow just lets out for all he is worth and his energies are momentarily devoted to that and nothing else ; all the headwork is done beforehand in cultivating correct action and quick response. But from sprinting distance onwards more time is available for mental supervision during the actual event, with the result that its advantages become more and more significant. Have you ever heard of a coloured man who had any chance against a well-trained white at long distances ? All the same, when we start seriously to train blacks for this kind of event we shall probably get the same results as we’ve already done in sprinting and boxing.

Again, sprinting probably requires less actual thinking than any other form of exercise except casual walking. Oh no ! I’m not suggesting that those who go in for it are in any way less brainy, for that is not the case ; they merely take naturally to a form of sport for which they are physically and mentally suited, knowing instinctively that they can obtain results more quickly in that way, and very wisely they make the most of such temperamental urge. We already know that a sprinter’s finest period is the shortest of all in duration—just a few years around the early twenties and no more.

Once beyond sprinting, however, most forms of athletics depend for their success on brain work during their performance ; more time is involved not only in training but in the competition itself, for experience and judgment come increasingly into the picture. Correct judgment of your own abilities becomes the supreme test, and that can be obtained only by persistent experiment. This is the snag that holds up the majority of athletes because, and only because, they have not been long enough at the game to assess their ability correctly and adjust their action accordingly.

Why do fellows fall out of a race or fail to finish anywhere near where they know they ought to ? Why do boxers take an unmerciful hammering and still try to carry on ? Simply because they haven’t adequately judged what they were up against and have not therefore devoted a, good deal more time and trouble to prepare for their contest. It is nearly always the same, and the lesser lights retire temporarily defeated yet knowing that they could most certainly do far and away better if they punished themselves with more intensive preparation.

No matter what the event, whether cycling, boxing, rowing, running or anything else where more than a few seconds are required for its achievement, success can always be realised by weighing up the conditions and thereafter undergoing adequate training to meet them. Anyone can put in a furious burst to start with, but unless he is pretty certain of immediate success—

53

and be almost certainly isn’t—he is making a free gift of the event to his rival or competitors. Admitted you can’t always do the ri”ht/thins, but reasonable caution has won more contests than it IrTs lost while taking a chance more often brings about the reverse. “you can look at it this way. Physical growth is already well on its wav even before the time”of birth ; whereas reason on account .fits being a later stage in development, doesn’t make a start until a child begins to speak, and its development period long outlasts that of mere physical expansion. So far as the mind only is concerned an athlete would probably be at his best for prolonged exertion when he was between thirty-five and fifty, but by that time his muscles and whatnots have become set and have lost so much elasticity that mental direction, however efficient, may not he sufficient to outbalance the physical superiority of men considerably younger.

It is evident, then, that a man’s best time for protracted competition must be assessed from a combination of physical and mental maxima, and this leaves us with a range of from about twenty-five to forty-five years. Of course you are bound to strike an exception here and there. Ballington, the South African, beat world’s track record by a very wide margin in his 100-miles race at the age of twenty, and another man of more than twice that age did the same thing though not so well at an earlier date. Yet that actually doesn’t mean so much, for Ballington could very certainly have done even better had he been able to continue training, just as the older man would almost surely have made a hotter show had he taken to the game when younger.

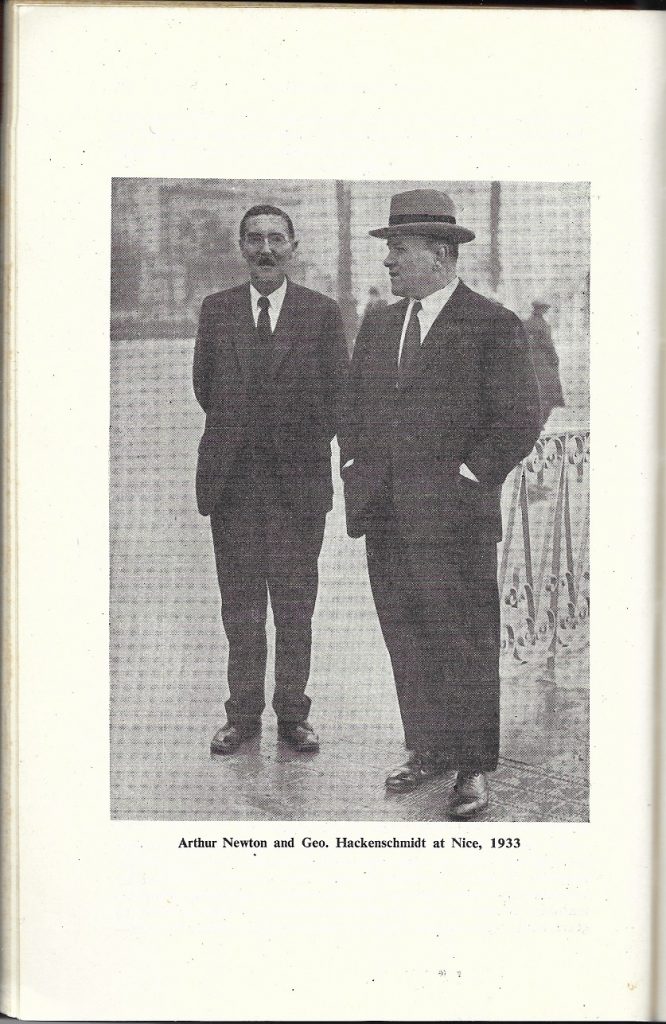

That may all sound straightforward enough but there’s still another point which is no less so ; and that is at the age of, say, twenty-five, a man’s physical capabilities are certainly at their peak. The mere fact that a sprinter begins to lose a trifle of his speed after that age shows that all his muscles must be similarly affected. Not only that, but if he is at his physical peak he must also be at his recovery peak at the same time. And as stamina is assuredly a physical attribute he can be at his stamina peak then too. Actually “of course we don’t all go in for training to bring us to our ” peak ” at that age ; and consequently where stamina and speed are wanting, they can be very considerably improved at a later date by conscientious work. But it seems to me to be unlikely that a man well over twenty-five could ever get quite to the standard of speed, strength and recovery which might have been his at that aero—which would have been his had he been perfectly trained from childhood. But then none of us is anything like perfectly trained throughout all the years of bodily growth, though probably the ” born athlete ” gets nearer to it than the rest of us. Hackenschmidt, for instance, who was admittedly the finest physical specimen of the modern world, spent almost every moment he could spare during his childhood and youth at speed- and body-building exercises and, having been born a ” strong man “—like Bach was a ” born musician ” or Sir Oliver Lodge a ” born thinker “—was

54

able to outpoint any and every man he ever came up against. To my mind it is only in a case of this sort that the man-in-the-street meets his master ; so many ” born athletes ” fail to attain their real status for want of continuous and intensive training, that the man who really does tackle the job thoroughly stands more than a good chance of beating the best of them. That he does stand such a chance is proved over and over again. The ” born ” runner recognises his ability without having to look for it and. like born musicians or born mathematicians, shows up at an early age. Yet neither Ballington nor I were ever particularly attracted in this way ; both of us took up running with the idea of learning something we were unused to, something which would improve health and keep us reasonably fit. It was only after (in my ease nearly twenty years after) we had got to that stage, that top class performances began to appear on the horizon as possibilities, and then we had to get stuck into work more strenuously than we had formerly considered possible.

Don’t lose heart, then, if you’ve not reached the standard you’ve had in mind. Think it over carefully ; decide what is necessary in the way of training ; then set to again, and finally do even a bit more preliminary work than you decided. It CAN be done !