CHAPTER IV

MAN VERSUS HORSE

TWO of us had trundled a tested Government machine at a fast walking pace from the City Hall at Maritzburg (South Africa) to Durban Town Hall in order to measure the exact distance, which turned out to be 54 miles 1,100 yards. This was the Comrade’s Marathon Course, and in the next month or so we should be racing over it competing against other runners and, for a novelty, against a man on a horse.

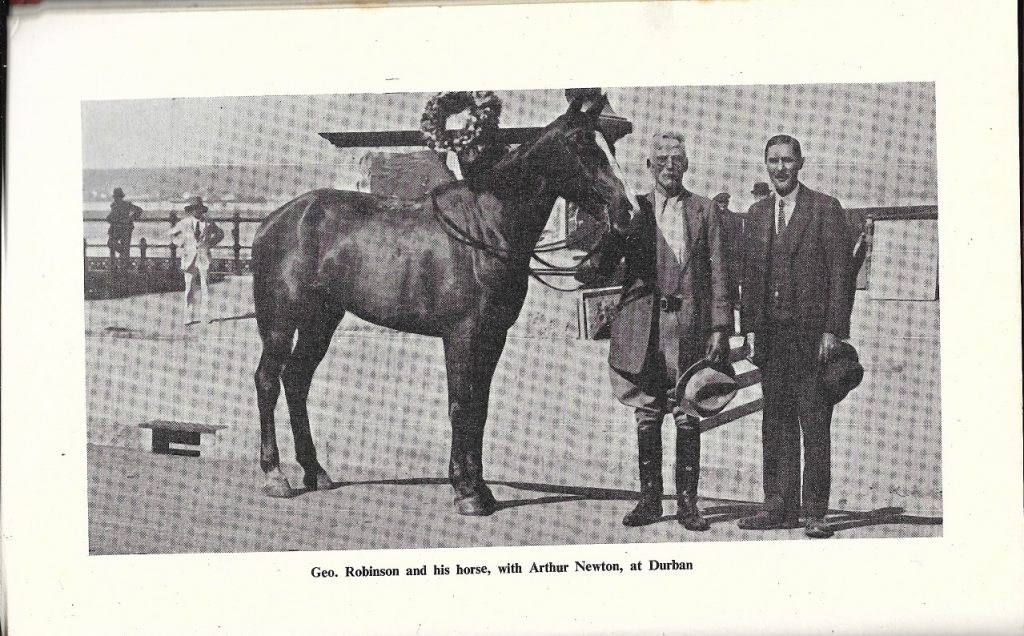

Mr. George Robinson was a well-known Natal farmer and Mr. Vie Clapham, the promoter of the race, had induced him to train a horse and try his luck against us. He took to the job seriously and, having picked his mount, went out daily for long journeys on the road. He wasn’t going to take any chances ; he saw to it that both horse and rider were in top form for the ordeal. Mr. Robinson himself was the jockey.

Personally I considered that the men were likely to turn out winners, but the general public, according to the press, favoured horse and rider. Anyway, we should soon know.

May 24th came along—Empire Day, always the day of the race —and the Mayor of Maritzburg sent us off on our long journey afoot, the horseman starting three minutes later so as not to get in the way of the competitors while they were all bunched up.

15

This promised to be interesting and I found my mind always speculating about it. For three miles I trotted along at about nine miles per hour and then came the first big hill. They are big hills in Natal, very much stiffer than anything I’ve since seen in the South of England over which I have travelled considerably. We had something like 800 feet to climb here, and I was less than halfway up when I heard a horse approaching from behind. Of course it might be ” the ” mount, but I wasn’t going to look back, because other riders were using the road. Trotting quite easily at between eight and nine miles per hour he caught me up presently, and I found it was Mr. Robinson after all, though I had hardly expected to see him so early in the day. We ” cheerio’d ” each other and before long I lost sight of him.

I didn’t feel a bit downhearted at this, rather the other way round in fact, for I knew that pace in the early stages of such a race was fatal to a man and thought it might have the same effect on a horse. There was plenty of time ahead and I confidently looked forward to turning the tables later on. In the meantime H. J. Phillips, my chief rival, who was a quarter of a mile ahead when the horse passed me, was constantly increasing his lead— ten miles further on he was a mile and a quarter in front—so I had plenty to think about.

I carried on, generally travelling at about nine miles per hour, less uphill of course and rather more on the downgrades and felt I was getting along quite well. When I passed the hotel at Drummond, halfway to Durban, I enquired about the position and was told that Phillips was then only half a mile away and was slowing down ; also that the horse, after a rest of five minutes, was still going well and was all of a couple of miles ahead.

The thirty-mile mark arrived and I caught up with Phillips at last and, being now in the lead, proceeded to widen the gap so far as the running was concerned, but never did I get a sight of that horse. Forty miles, and except that I was leading by a greater margin, the position was just the same. Where on earth was that jockey, I wondered ?

By now I was getting a bit tired, of course, but that didn’t worry me because I knew that the last fourteen miles to Durban were nearly all downhill, dropping from over 2,000 ft. to sea level. As there was no sign at any time of the rider I thought he must have stopped at some wayside hotel to feed and water his mount, and that I must have passed him while he was at it.

But now I had other things to occupy me ; there was a continual stream of motor traffic along the road, which was mostly macadamised but not tarred, and there were times when I couldn’t see twenty feet in any direction on account of the dust. But the never-ending down-gradient made running comparatively easy and I got along so well that I was always increasing my lead over the rest of the field.

Ah ! Durban at last ! I came to the tram tracks at the top of the Berea and from there on felt I was being closely inspected by

16

crowds of people—one tram even kept pace with me for a couple of hundred yards—both in vehicles and alongside the road, and I’ve always been one of those who dislike publicity. Anyway, if I was tired I couldn’t show it while these thousands were looking on, and no doubt the crowd and their encouragment helped to spur me on.

A final mile on the flat to the Town Hall and in a few minutes it was all over. I soon discovered why I hadn’t seen the horse— Mr. Robinson had arrived more than an hour before ! His time was 5 hrs. 11 min., altogether better than anything I had imagined possible ; mine, 6 hrs. 24 m. 45 sec. and Phillips’ 7 hrs. 5 min. seemed very mediocre by comparison, and I was keen indeed to meet Mr. Robinson and discuss things.

He told me he had chosen a mount that was exceptionally good at that sort of thing, and that with the three months of training he had given it he was pretty confident of the result. He had, he said, almost run it to the reasonable limit, though it could have managed perhaps another eight or ten miles ; had the distance been much further however he would have stopped rather than risk any serious damage, for the horse was always his first consideration. It was a bit stiff after its long journey, but with a day or two’s rest would be as good as ever.

This outstanding triumph was, of course, due to the rider himself, and was all the more impressive when you realise that he was close to the ” three score years and ten ” stage ! I lift my hat mentally to him every time I think of our contest.