ABERDEEN AAC

W.Hunter Watson August 2015

(This account of Aberdeen AAC gives some background information in order to emphasise that, although this club was founded in 1952, its roots extend back to much earlier years.)

Aberdeen AAC was formed in 1952 following a public meeting which was attended by J. A. Cavanagh, the father of Ian Cavanagh who later that year won the S.A.A.A. youths’ long jump title with a clearance of 6.39m. (J.A. Cavanagh became Vice President of Aberdeen A.A.C. He remained in that post until 1955.) The newly formed club managed to arrange at least one match in the summer of 1952, one against RAF Dyce. (The team representing RAF Dyce consisted of young men who were based at the Dyce aerodrome while doing their National Service.) Ian Cavanagh failed to win his speciality, the long jump, but did win both sprints and hence helped Aberdeen AAC to win the match.

The President of the newly formed Aberdeen AAC was Jimmy Adams who had been actively involved in athletics in Aberdeen for over 30 years as an athlete and an administrator. He seems to have been an enthusiast and to have been highly regarded by the young people who had been attracted into athletics by the formation of the new club. One of those young people was Steve Taylor who went on to win the S.A.A.A 3 mile championship in 1961 and 1962 and the 10 mile championship in 1970. Steve has stated that, in the early days, he regarded Jimmy Adams as a “father-figure”.

Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War there were several athletic clubs in Aberdeen and much competition was organised for athletes within the city. Jimmy Adams had been the Vice President of the North Eastern Harriers Association which played a major part in organising that competition. One of the events which it helped to organise in conjunction with Aberdeen Football Club was the annual Athletic Sports Meeting at Pittodrie Park, as Aberdeen FC’s ground was then called. A study of the 1931 programme for that meeting reveals that there were then seven open athletic clubs in Aberdeen, four for men and three for women, though only two of those open clubs could be regarded as significant as far as inter-club competition was concerned, namely Aberdeenshire Harriers (the Shire Harriers), founded 1888, and the Aberdeen YMCA Harriers (Aberdeen YM), founded in 1912. In addition, there was the Aberdeen University Athletic Club which at that time was active as a separate entity to a greater extent than it is now.

Jimmy Adams had competed with great success in the high jump. He claimed that in the course of over 100 competitions within the UK, including two internationals, he never failed to make the top three. One of those internationals was the Triangular International which involved England (including Wales), Ireland and Scotland and which Scotland won in 1923. The Official Centenary History of the S.A.A.A. notes that this success was in no small measure due to the magnificent performance of Eric Liddell in winning the 100 yards, the 220 yards and the 440 yards. That performance was perhaps more remarkable than is generally realised: according to Jimmy Adams, Eric Liddell ran those races in an outsize pair of borrowed spikes with cotton wool stuffed in the toes: he had left his own spikes at the White City where he had been competing prior to the International at Stoke.

The President of the Shire Harriers had been Fred Glegg, who was also President of the S.A.A.A. during the war years. Unfortunately, Fred died in October 1946. Had it been otherwise, the Shire Harriers might still be in existence and have been one of Scotland’s oldest Harrier clubs, the first Harrier Clubs, Clydesdale Harriers and Edinburgh Harriers, having been formed in 1885, only three years before the Shire. The Shire Harriers did function until at least 25 April 1950 when there was an Annual General Meeting held. The minutes reveal that all of the places on the Committee were filled except that of secretary. The previous secretary, Ralph Dutch, had completed his university degree and was, required to do his National Service and hence give up his post as the Shire secretary. With no-one being willing to take on the duties, the club ceased to operate.

Keeping the Shire Harriers going after the end of the 1939-45 War had posed considerable difficulties in part because of a lack of competition. Whereas in Edinburgh and Glasgow the pre-war open clubs largely survived, the Shire Harriers was the only open club to do so in Aberdeen. This meant that there was no longer a North Eastern Harrier Association to organise local competition. The competition provided by the Shire Harriers in the post-war period seems to have been largely handicap competition involving only club members. That would not have been particularly motivating. Another problem that the Shire Harriers had was finding a suitable training venue. They used the rugby pitch at Hazlehead. That was satisfactory in the summer, but not in the winter.

According to Arthur Lobban, the last secretary of the Aberdeen YM Harriers, the last AGM of that club was in August 1939. At that AGM it was agreed that the club should go into abeyance until the war situation was clear. War was declared on 3 September 1939 and those members of the YM who survived the war did not seek to resurrect the club when the war ended. However, it may have been significant that when a public meeting was held in 1952 with a view to forming a new club, there were reportedly eight former members of Aberdeen YM present. There are grounds for arguing that Aberdeen AAC is actually a successor to the Aberdeen YM Harriers Club:

the first president of Aberdeen AAC, Jimmy Adams, had been a Vice President of the Aberdeen YM Harriers club;

the first secretary of Aberdeen AAC, Robert Miles, had also been member of the Aberdeen YM Harriers club;

the first constitution of Aberdeen AAC made reference to the “Y.M.C.A. Section”;

Annual General Meetings of Aberdeen AAC were held in YMCA premises until at least 1966.

Obviously Aberdeen AAC had more success than the Shire Harriers in maintaining the interest of its members and there are several possible reasons for this:

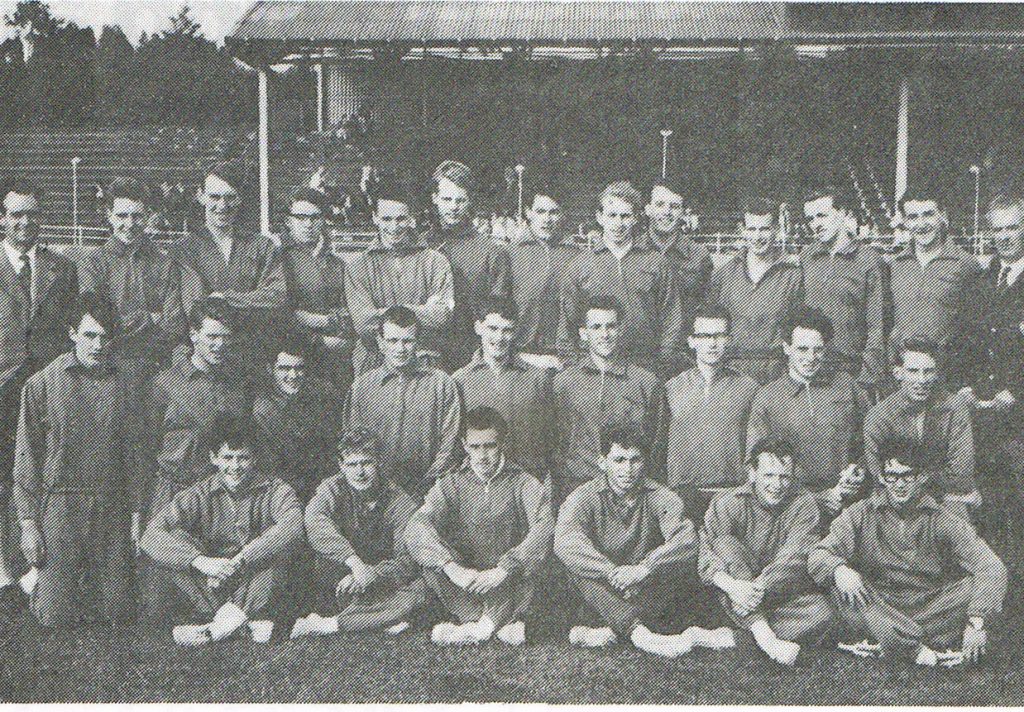

Jimmy Adams was successful in persuading the Aberdeen Council to permit Aberdeen AAC to train at Linksfield Stadium, a football stadium with an excellent running track;

club members were encouraged to raise their sights and compete in major championship events; in both 1955 and 1956 an Aberdeen youth won the Eastern District Youth Cross Country Championship (and in 1955 an Aberdeen AAC youth team, which included Steve Taylor, was second in the team race) while in 1956 Pat Bellamy and Alice Robertson (both Committee members) won three S.W.A.A.A. titles between them (high jump, 100 yards and 220 yards);

Aberdeen Corporation began to put on a major sports meeting each summer. (Athletics Weekly printed the results of the meeting held in 1954. I had my expenses paid to travel from Edinburgh to compete in the meeting held in 1956.)

Beginning with the match against RAF Dyce, the new club generated sufficient publicity to make people in and around Aberdeen aware of Aberdeen AAC, something that increased the probability that it would attract new members.

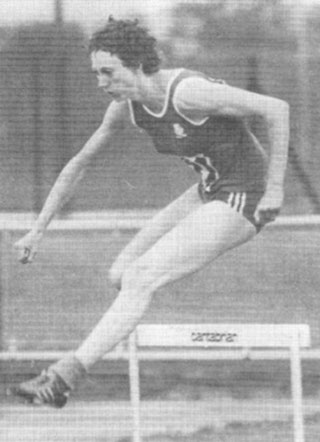

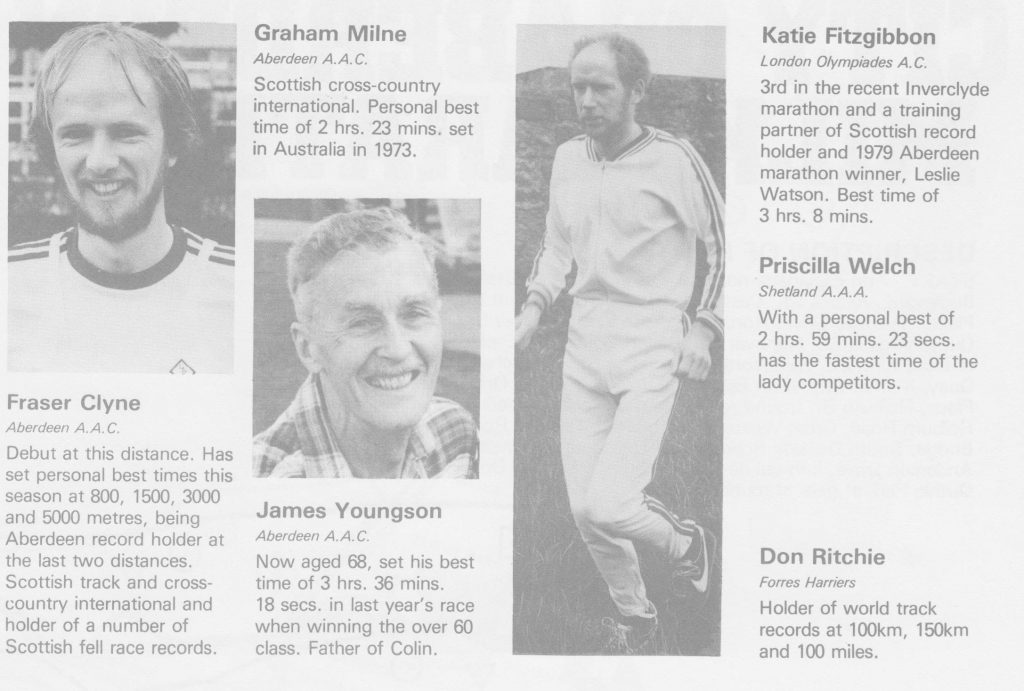

One new member who joined Aberdeen AAC in 1961 was Alastair Wood, who had won the S.A.A.A. 6 mile championship in 1958, 1959, 1960 and 1961. In 1962, after becoming a club member, he decided to attempt the marathon and discovered that he had a talent for this and, indeed, greater distances. In 1962, after being second in the A.A.A. marathon, he was selected to compete in the marathon in the European Championships. He finished fourth in that event. He continued to compete with great distinction in distance and ultra-distance events for many years and, directly or indirectly, inspired many Aberdeen AAC athletes to undertake the training that helped them to run fast marathons. Between 1966 and 1990 there were twelve members of Aberdeen AAC who ran a marathon in a time less than 2hr 20 min, a statistic that few clubs in the UK could better. Aberdeen AAC, encouraged by Steve Taylor, played its part in promoting the marathon: in 1979 it organised the first of the city marathons in the UK. The winner was Aberdeen AAC athlete Graham Laing. Graham went on to win the S.A.A.A. marathon in 1980 and in 1981 he finished fifth in the first of the London marathons. The following year he represented Scotland in the marathon in the Commonwealth Games, something that his clubmate, Fraser Clyne did four years later.

Unsurprisingly, the group of Aberdeen AAC athletes who were doing the hard distance training at that time did well in the Edinburgh to Glasgow road relay: in the ten races between 1980 and 1989 Aberdeen won three and were placed third in four of them.

Although from the time that Alastair Wood joined the club until the time that the road runners broke away to form the Metro running club (around 1989) there was a great interest in road running in Aberdeen AAC, track and field was not neglected. Evidence of this was the decision of Aberdeen AAC to be one of the eight clubs to form the Scottish Athletics League in 1972. This gave Aberdeen AAC athletes the opportunity to compete against the best athletes in Scotland on the best track in Scotland. At that time and for a few years thereafter each of the four annual meetings of that league was held at Meadowbank on the track that had been laid for the 1970 Commonwealth Games. (In 1995 and again in 2015 Aberdeen AAC won the Scottish Athletics League title.)

By 1974 it became obvious that there were some talented young athletes who wished to join Aberdeen AAC but for whom the club was unable to offer sufficient competition to keep them motivated. As a consequence a decision was made to join the Scottish Young Athletes League, something that it did in 1975. (Aberdeen AAC has won the Scottish Young Athletes League title only once. That was in 1981.)

A major campaign to attract youngsters into the club was successful in more ways than had been anticipated. Not only did many youngsters join the club but a significant number had parents who were willing to become involved by joining the club committee, by coaching or by officiating. Aberdeen AAC became a club which developed expertise in organising events, so much so that when televised international road races came to Aberdeen the club had no difficulty providing a sufficient number of qualified judges and timekeepers to cope. The club’s proven ability to do this may have been one factor which led to the Scottish senior championships coming to Aberdeen in 2015. That is the first time that these championships have been held outside the central belt of Scotland since 1892 when they were held in Dundee.

The publicity given to the club in 1975 in order to attract a sufficient number of boys for it to be able to compete in the Scottish Young Athletes League, at that time a purely boys league, also attracted girls, but not sufficient for the club to be confident that it could field a team in the Scottish Women’s Athletic League. However, it eventually became evident that this was possible and Aberdeen AAC joined the Scottish Women’s Athletics League in 1976. (Aberdeen AAC has never won this league title but regularly finishes in the top three.) Unlike the Scottish Athletics League, the Women’s League caters for the younger age groups so, as far as track and field was concerned, the club could offer competition to all who wished to join it. (During the winter some members choose to take part in indoor competition but others compete in cross country events. Some local events are organised by the club, but most in which members compete are championship or league events which take place at some distance from Aberdeen and to which buses are sent.)

When Aberdeen AAC was expanding rapidly there was no question of having a waiting list. Partly as a consequence, Aberdeen AAC became one of the biggest athletic clubs in the UK. In 1988 when the club’s numbers peaked: subscriptions had been received from 606 members of whom 517 were aged 11 or over. In 1994, around five years after several road runners had left the club to form Metro, the S.A.A.A. released data which revealed that Aberdeen AAC had then 494 members aged 11 or over. According to that data, Aberdeen was almost 50% larger at that time than Scotland’s second largest club, Pitreavie AAC.

For a time there was pressure from the S.A.A.A. on clubs not to admit athletes in the 9-11 age group, a pressure that was resisted by Aberdeen AAC for good reason. For example, among the boys who began competing for Aberdeen AAC in that age group were Mark Davidson and Duncan Mathieson. Both went on to represent Scotland at the Commonwealth Games, to set Scottish records and to win Scottish titles.

One feature of Aberdeen AAC is the number of members who continue to compete as Veterans, or Masters, as they are now called. At the Scottish Masters Championships, the club whose members have the greatest number of successes is awarded a trophy. According to Stan Walker, the club Vice President, Aberdeen AAC has been awarded that trophy for the ten years up to and including 2015. Stan was a member of the UK 4 x 200m relay team that won at the 2015 European Masters Championships. Another club member, Fiona Davidson, won the triple jump title for her age group at the same championships.

At present Aberdeen AAC seems to be in good health and, judging from the dedication of those responsible for the club, it is likely to be so for some time to come. Hopefully, some of the young people currently in the club as competitive athletes will continue in athletics by filling the other roles necessary for athletics to continue to flourish in Aberdeen, i.e. roles such as administrators, officials, coaches, team managers, conveners, etc. Given that organised athletics in Aberdeen has existed for well over 100 years and given the worldwide popularity of the sport, it is difficult to imagine that there will come a time when no-one in the city will be available to do the needful. It is to be hoped, though, that Aberdeen AAC will not have to cope with a world war as clubs had to do twice in the twentieth century!

ABERDEEN ATHLETICS MEMORABILIA

- Hunter Watson January 2016

Introduction

Soon after becoming secretary of Aberdeen AAC in 1975 I began to make enquiries about the history of athletics in Aberdeen. As a consequence I was put in touch with a number of people able to supply me with information. A few, who seemed appreciative of my interest in the subject, were good enough to give me some of the items in their possession which related to athletics in Aberdeen. These included Ralph Dutch, the last secretary of Aberdeen’s first athletics club, the Aberdeenshire Harriers, which was founded in 1888. He gave me the minutes book of that club and in this paper I have written at some length about what is contained in that book which covers the period from June 1923 to April 1950.

At the age of eighty I have decided that the time has come for me, in my turn, to pass on my athletics memorabilia. I am grateful to Aberdeen University for agreeing to place it in its Special Collection.

With the agreement of the Committee of Aberdeen AAC, I have included within the material which I am donating some old minutes of Aberdeen AAC. Obviously much information can be derived by studying those minutes. However, there are easier ways to obtain information about Aberdeen AAC from the material donated. For example, I have also donated to the Special Collection my scrapbooks containing press cuttings relating to the club and also club newsletters, club yearbooks and club membership cards.

Ralph Dutch

Ralph Dutch was a colleague of mine at the Aberdeen College of Education. He was the last secretary of the Aberdeenshire Harriers Club (the Shire Harriers). That was Aberdeen’s first Harriers Club and survived for 62 years from 1888 until 1950 when Ralph Dutch was due to be called up to do National Service after his graduation from Aberdeen University and no one else was prepared to fill the post of club secretary which he, of necessity, had to vacate. Ralph gave me a number of items that had been in his possession as secretary: a few items of correspondence, the secretary’s cash float, a number of Shire Harriers lapel badges, a Shire Harriers medal and, of greatest historical interest, the Shire Harriers minutes book that had remained in his possession. In this section I have written at some length about information that can be gleaned about the Shire Harriers by studying that book.

When the minutes book was started the address of the club was given as King’s Crescent: following the end of the First World War the club succeeded in having a clubroom erected there. Some use might have been made of that clubroom by members who took up boxing(!) though boxing competitions seem to have been held in the Music Hall. According to Jim Ronaldson, who was narrowly beaten by Dunky Wright in the 1923 full marathon from Fyvie, “The boxing section destroyed the club; young men joined the boxing section instead of the athletics section.” Colin ***Youngson’s history of the Shire Harriers’ marathon speculates that the reason that there were no marathons or other long road races in the period 1926 1928 was that the “athletes had been overshadowed by the boxing fraternity”. It appears from the Shire Harriers’ minutes book that there might be considerable truth in the views expressed by Jim Ronaldson and Colin Youngson. The minutes reveal that there was an AGM on 17 September 1926 and at that AGM the secretary stated that to make up a report for this meeting used to be a serious matter for him but that this year there had really been nothing done by the club in the way of races, etc. to report on! Office bearers were appointed but seem to have achieved very little because there was no further entry in the minutes book until 2 February, 1928 when another General Meeting was held. According to the minutes of that meeting, the chairman stated that “this was the first meeting held of the club since it had again been instituted (sic)”. At that meeting not only were office bearers appointed but dates of various distance races were agreed to. At a later General Meeting on 12 June 1928, dates were agreed for 100 yard, 220 yard, ¼ mile, ½ mile and 1 mile races. These were to be held on Riverside Road! (No doubt that was the road now known as Riverside Drive.) There was also reference to participation in a 1 mile relay race and also in a I mile team race organised by the North Eastern Harriers Association of which the Shire Harriers was a member. The Shire Harriers Club was again providing competition for its members and the “boxing section” of the club seemed no longer to exist.

At AGMs there was regularly expressed concern about club funds and ideas were put forward about fund raising. These concerns were to disappear following the AGM held on 6 September 1928 when members were introduced to Mr F. J. Glegg (Fred Glegg). According to the Minutes, Mr Glegg stated that he would wipe out the £2 – 2 – 0 ½ deficit which the club had incurred during its first season (after being reconstituted). Further, since he considered that the club still had an uphill fight he would be very pleased to make up any deficiency that might occur as a result of unforeseen circumstances in the future. (It seems that this was never necessary apart, perhaps, during the Second World War when Fred Glegg seemed to keep the club in existence unaided by a committee.)

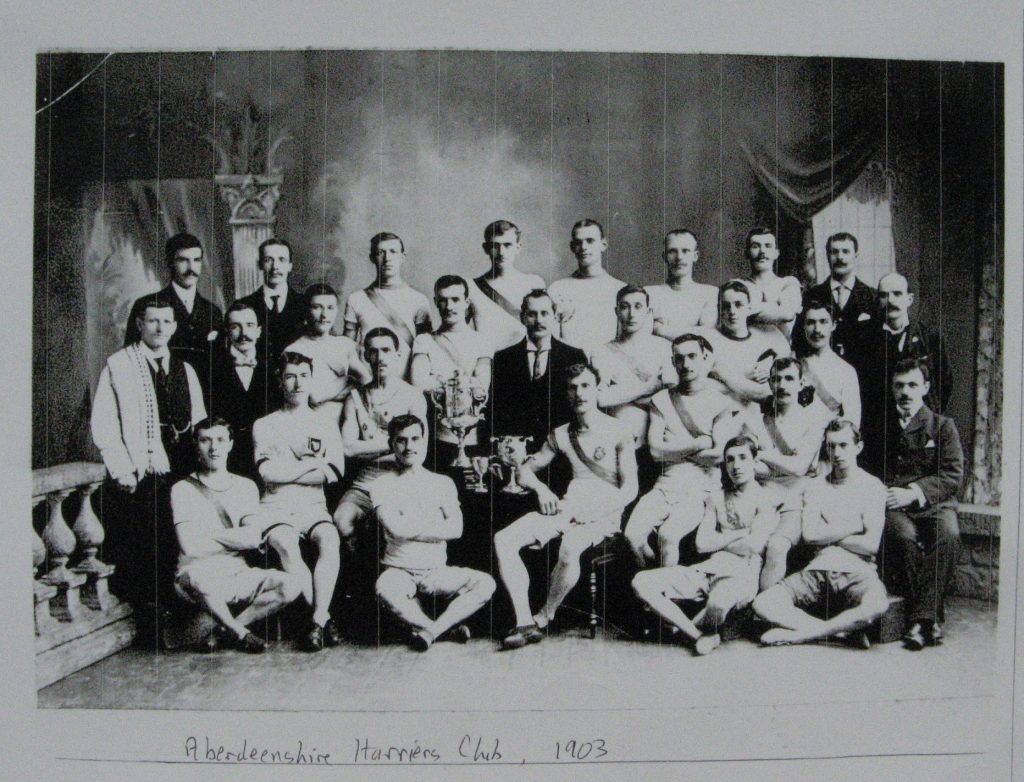

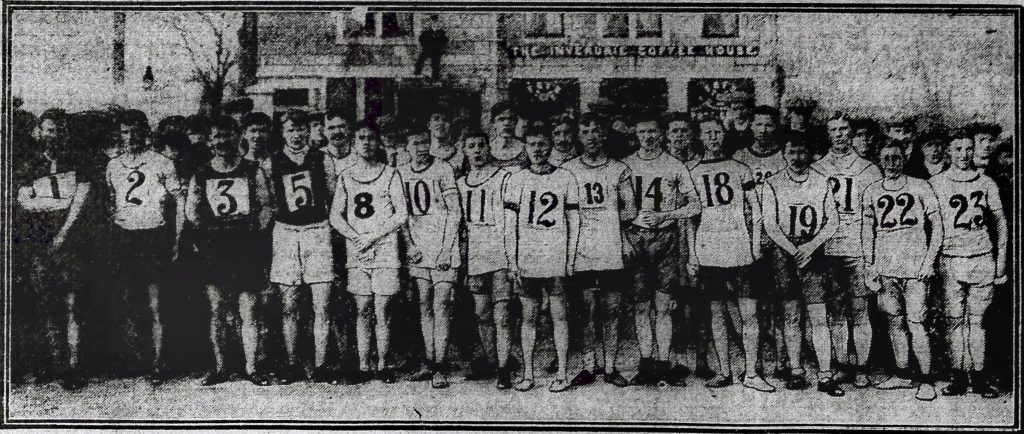

In 1929 a photograph was taken of the Shire Harriers with the athletes in their strips, the officials in their suits and the trainer (who was paid for his services) with a towel over his shoulder. I have no doubt that Fred Glegg is the man second from the left in the second row. Both he and the man second from the right in that row are wearing lapel badges which seem to be identical to the lapel badges which Ralph Dutch gave me. In the foreground of that club photograph are seven impressive looking club trophies.

According to John Keddie’s Centenary History of the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association, F. J. Glegg was President of the Association during the War (1939 – 1946) and in his will bequeathed £50 for a Challenge Trophy. Unfortunately Fred Glegg died in October 1946. It is the opinion of Ralph Dutch that had he not died so early then it would have been likely that the Shire Harriers would have survived.

Returning to the minutes book of the Shire Harriers, it is noteworthy that at the monthly meeting on 4 February 1930 there was a proposal that the club be wound up and this was seconded! An amendment that the proposal be left over to the AGM was also seconded and carried on the casting vote of the chairman. Thereafter things not only seemed to run fairly smoothly until the outbreak of the Second World War but also to be developing in a promising way. For example, at the Annual General Meeting held on 13 May 1933 it was agreed that the summer athletics competitions be held at Hazlehead and in the Duthie Park. It was further agreed that, in addition to the running events that had been held on Riverside Drive in the past, there be added a long jump, a high jump and a shot putt to the summer competition programme. (These field events could hardly have been held on Riverside Drive.) The following year, on 14 May 1934, it was further agreed that a discus and a javelin be purchased. On 23 January 1936 there was another interesting development: it was agreed that the club should have a junior section open to youths between the ages of 14 and 18 years of age. Also in 1936, at a meeting held on 9 May, it was agreed that “the Ladies Athletic Club” could use the Shire Harriers clubrooms two nights per week for their winter training at a charge of 3/6 per month “including coal and gas”. The Shire Harriers had not become a mixed club, but had taken a first tentative step in that direction. In general, the Shire Harriers showed signs of developing in the ways that the Edinburgh clubs had done in the late nineteen fifties and the nineteen sixties. (I was involved in athletics in the Edinburgh area at that time.)

At the General Meeting of the Shire Harriers held on 7 September 1937 Fred Glegg observed that the club “was now in its fiftieth year”. That confirmed the information that had been given to me by Alex King who was a member of the Shire Harriers in 1912, the year in which he won the “marathon” from Inverurie to Aberdeen: he had told me that the Shire Harriers had been founded in 1888.

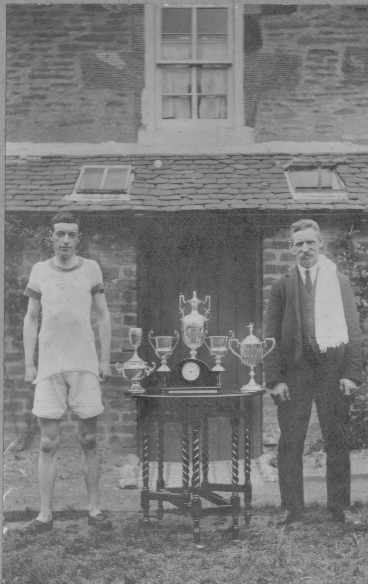

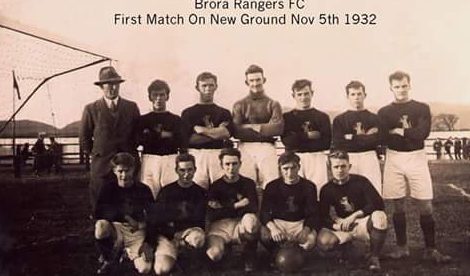

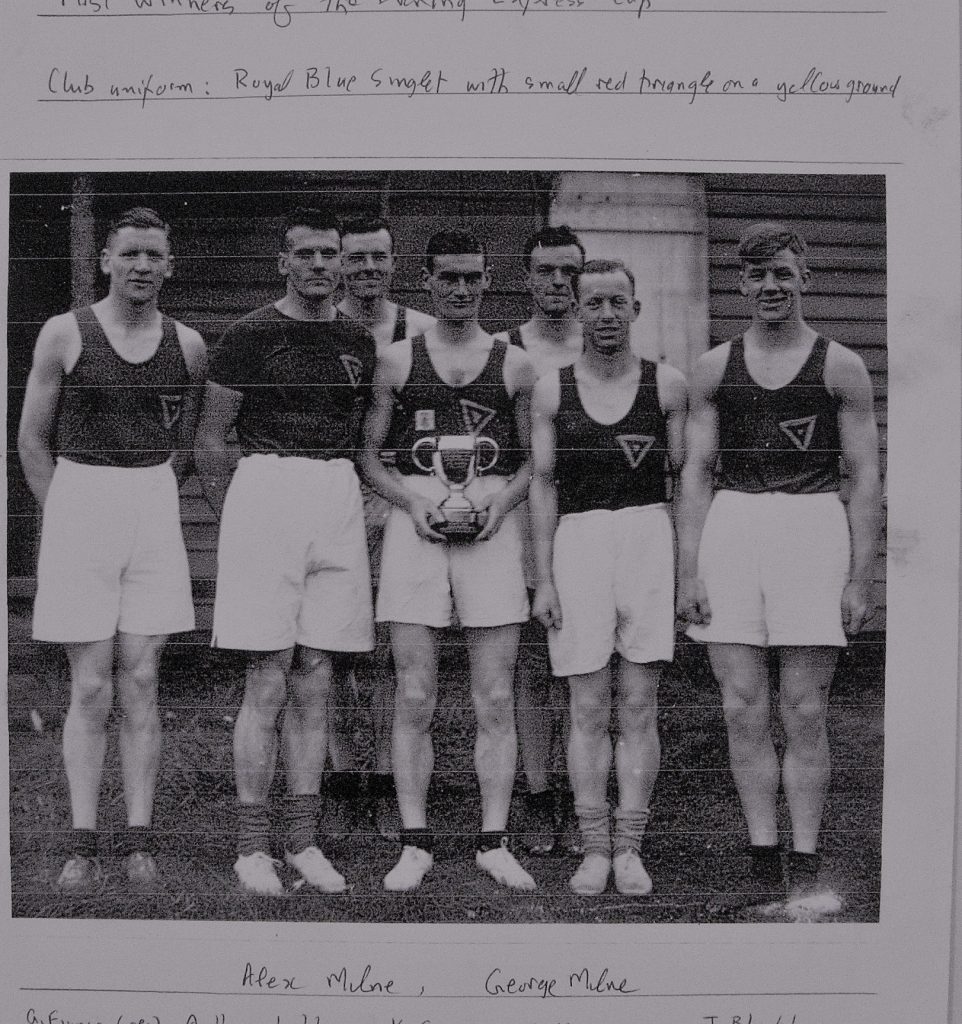

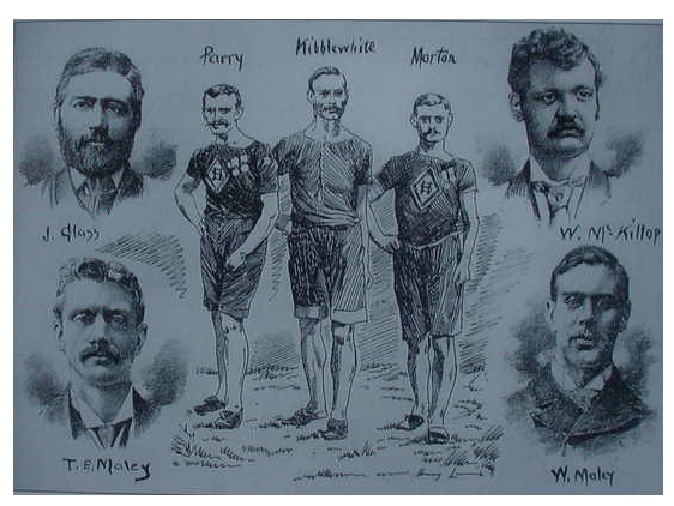

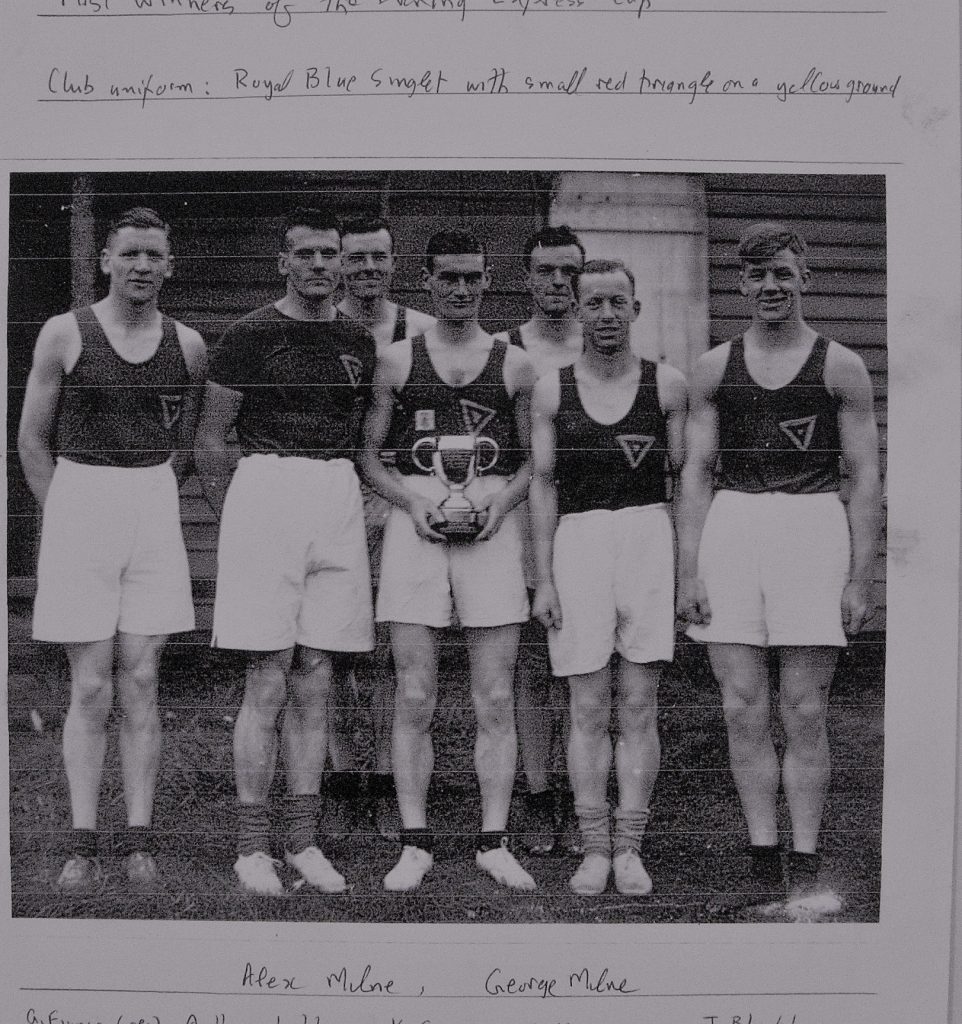

Aberdeen YMCA team, winners of the North Eastern Harriers Round the Town relay of 1938.

Back Row: Alex Milne and George Milne, Front: G Finnie (reserve), A Lobban (then Secretary), K Gray, S Kennedy, J Blacklaw

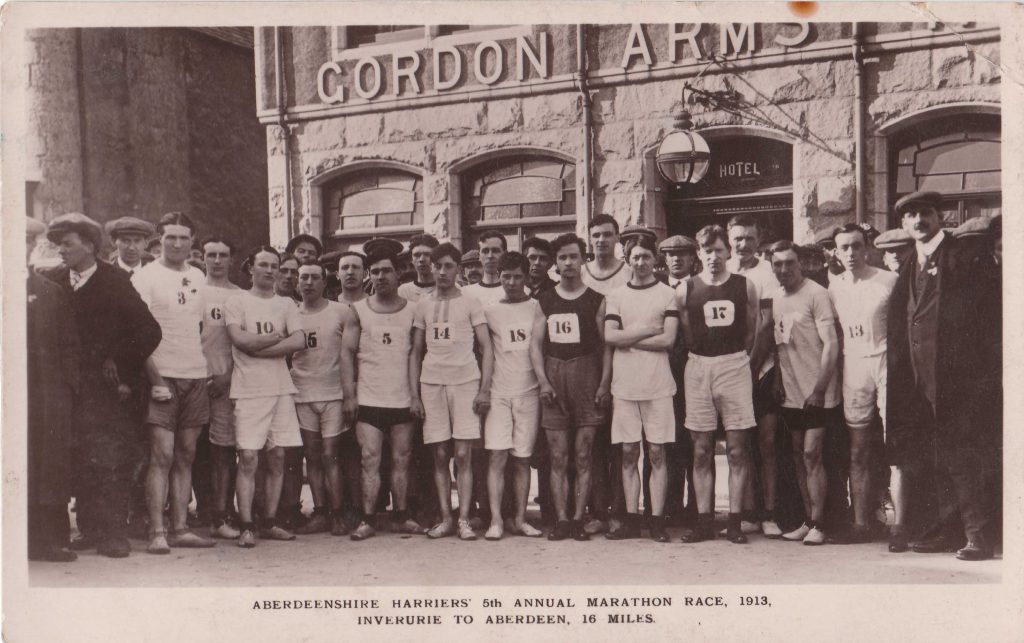

A marathon craze had swept the UK after the drama of the marathon in the 1908 London Olympics and the Shire Harriers was one of the clubs that began to stage local marathons At that time the distance for the marathon had not been standardised and a marathon was simply a long race staged on a road. The first of the Aberdeen marathons was held on Saturday, 20 March, 1909. The course followed the north Deeside road from Banchory to Aberdeen. A press report which appeared on 22 March 1909 noted that “The brief interval of fair weather had improved the roads to a wonderful degree and the runners were able to find a fairly hard surface for a considerable part of the way so that the running was not perhaps so hard as was expected earlier in the day.” (At that time the north Deeside road did not have a tarmacadam surface.)

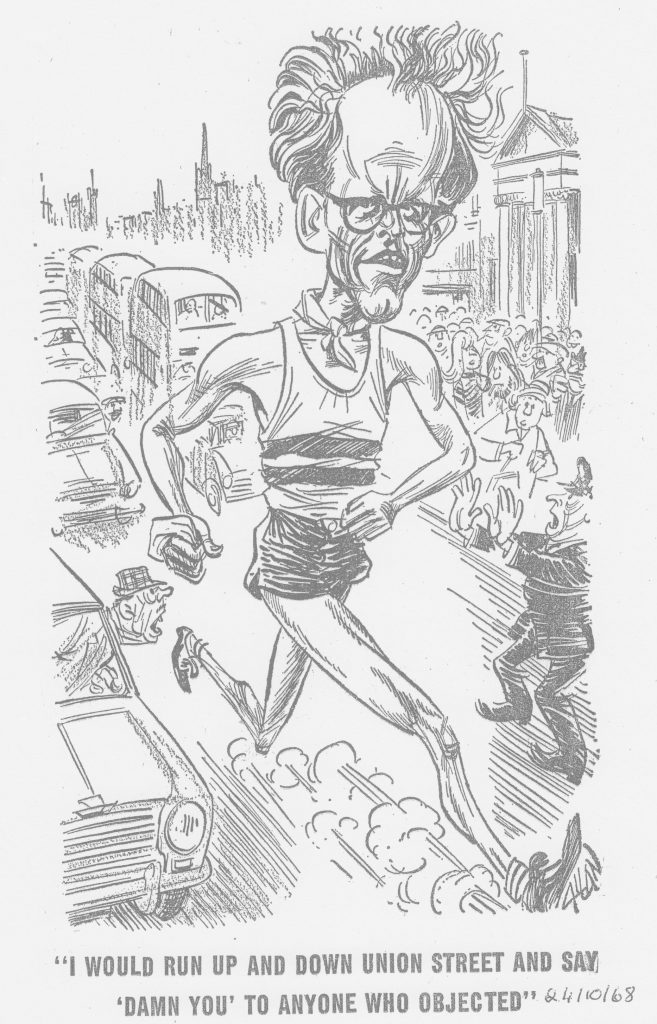

The press report of the race also noted that “At Mannofield runners had difficulty getting a clear passage through the spectators. All the way down Union Street, along Union Terrace, Blackfriars Street and on to the finishing point in St Andrews Street the runner had only a passage about one yard in width and it is probable that even this space might not have been available had he not been preceded by a car. … In St Andrews Street the huge concourse of people was altogether beyond the control of officials and police. As the men came in they were hurried to Mr Jamieson’s premises in George Street where they were supplied with much needed refreshment and comfort.”

According to Alex King, William Jamieson was a publican who lived in a large house called Thorngrove at Mannofield and who donated a Marathon Cup to the Shire Harriers to be awarded to the winner of each of the “marathons” which they organised. He also provided a gold medal to be awarded to and to be retained by the winner of each marathon. Alex King clearly was in possession of the facts since he had won the Aberdeen marathon on three occasions, namely in 1912, 1913 and 1925. William Jamieson’s generosity towards the Shire Harriers manifested itself in other directions also. In particular, again according to Alex King, he met £100 of the £120 cost of the hut which the Shire Harriers purchased after the end of the First World War and to which reference was made above.

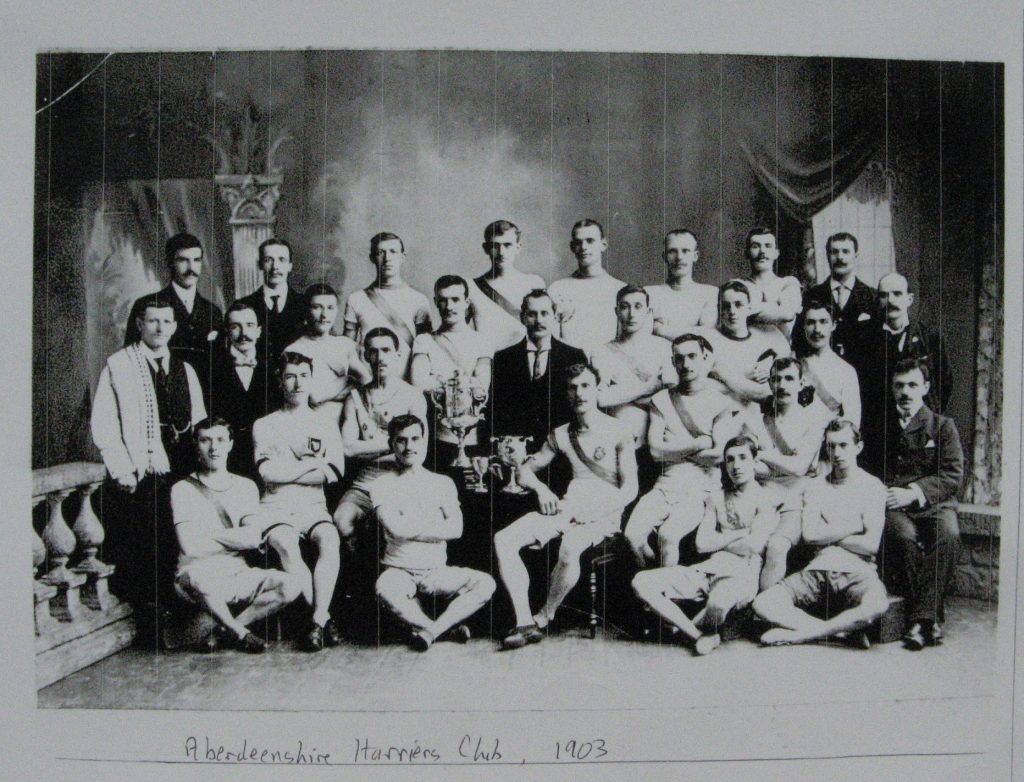

It is not known when William Jamieson first became involved with the Shire Harriers. However, a photograph was taken of club members in 1902 and this might have been taken shortly after William Jamieson became involved with the club, just as a club photograph was taken in 1929, shortly after Fred Glegg (another publican according to Alex King) became involved. In the 1902 photograph it is likely that William Jamieson is the man in the middle of the second row behind the trophies. There is a remarkable similarity between the two photographs, including the presence in each of a trainer with a towel over his shoulder.

The minutes book of the Shire Harriers reveal that meetings were held initially at King’s Crescent. They would have been held in the hut which the club had purchased with the assistance of William Jamieson. Presumably it was situated on the edge of the recreation ground to the north of Nelson Street. The same minutes book reveals that in the years preceding the Second World War meetings were being held in the club house at the Wellington Bridge. This club house was a building at the north end of the bridge which had once been an octagonal shaped toll house. No doubt the Shire Harriers paid rent for the privilege of using it. During the war years Fred Glegg seems to have paid this rent out of his pocket and also the club’s subscription to the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association.

A General Meeting of the Shire Harriers was held in the Wellington Bridge club house after the war on 6 April 1946. Fred Glegg was there in his capacity as president. A further General Meeting was held in that clubhouse on 9 May 1946. On the latter occasion it was (ominously) noted that F. J. Glegg was unable to be present and that the Vice-President had been killed in hostilities and hence a chairman would have to be appointed for the meeting. One was duly appointed and a businesslike meeting ensued. It was decided to hold events during the summer season provided the rugby field at Hazlehead could be made available for the months of June to August on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. (A tramcar terminus was situated within 100 yards of that rugby field so getting to it would not have presented a problem.) It was also agreed that the committee should look into the possibility of getting fresh quarters.

At a meeting on 14 May 1946 it was decided to combine the 1914-18 and 1939-45 Rolls of Honour into one scroll “including the one already hanging in the clubhouse”. The following names were to be added:

Alex Donald Lieut. London Scottish

Harry Donald Sub Lieut. Fleet Air Arm

John Gerrie Gunner R O

Lindsay Nunar(?) Private Scots Guards

- Stove Staff Sgt Royal Army Pay Corps

At a meeting held on 25 November 1946 it was intimated that the club had lost a faithful friend, the late Mr Glegg. He had been a faithful friend from 1928 and had been keenly interested in the club “to the last”. According to Ralph Dutch, Fred Glegg was about 48 years of age when he died.

At a meeting on 13 May 1947 it was agreed that nothing should be done regarding a combined Roll of Honour until the club again acquired a clubhouse in which the scroll could be displayed. The former toll house on Wellington Bridge had ceased to be used by the club in 1946. From 27 August 1946 the club used the rugby pavilion at Hazlehead for its general and committee meetings as well as for changing. However, that pavilion, which belonged to Aberdeen Corporation, was also obviously used by rugby players as well as by members of the Shire Harriers. Since the Shire Harriers failed in its attempt to again acquire a clubroom for its exclusive use, the scroll commemorating club members who had been killed in action during the First and Second World Wars was never produced.

The above noted five men were not the only former members of the Shire Harriers who had been killed during the Second World War. Another was William Chapman. According to his grandson, this former member “was killed in a German bomber attack on his home on the Beach Boulevard in August 1941 at age 33”. (Aberdeen was frequently bombed during the Second World War.)

At the final General Meeting of the Shire Harriers on 25 April 1950 there were some interesting items of business including a reference to a possible ladies’ section. However, the meeting was unable to find anyone willing to take over the duties of secretary from Ralph Dutch who was due to be called up after graduating from Aberdeen University that summer to do his National Service. As a consequence the Shire Harriers ceased to function

C. Adams (Jimmy Adams)

When a new club, Aberdeen AAC, was constituted in 1952 Jimmy Adams was its first president. Almost certainly it was due to his influence that, from its beginning, Aberdeen AAC catered for women as well as for men even though pre-war there had only been single sex clubs in Aberdeen and even though at that time in Edinburgh most, if not all, athletic clubs were single sex.

When he was a young man Jimmy Adams had been an international athlete who represented Scotland in the high jump in two of the Triangular Internationals that had been held in the nineteen twenties. He had also been a member of the Aberdeen YMCA Harriers Club (the YM Harriers), a club which, according to Alex King, was founded in 1912. Jimmy Adams had been a Vice President of that club. He also had been a Vice President of the North Eastern Harriers’ Association, a body responsible for organising competitions for the athletic clubs in Aberdeen between the two World Wars.

Jimmy Adams provided me with much information in letters which he wrote to me. He also provided me with memorabilia which included old press cuttings, old photographs, the SAAA Championship medals which he had won and various old programmes. Of particular interest to anyone conducting research into pre-war athletics in Aberdeen are likely to be the programmes of the Athletic Sports Meetings organised jointly by Aberdeen Football Club and the North Eastern Harriers’ Association. These programmes provide information about the athletic clubs in Aberdeen at the time (including ladies’ athletic clubs), athletes participating, officials and prizes. I regard the prizes as most attractive. Certainly they were much better than most of the prizes which I won when competing in (amateur) Highland Games meetings in the north-east of Scotland.

Arthur Lobban

Arthur Lobban had been the last secretary of the YM Harriers. When I spoke to him he informed me that the last AGM and prize giving of that club had been in August 1939 and that it had then been agreed at that meeting that the club should go into abeyance until the war situation was clear. The books of the club were “returned” to the YMCA in Aberdeen. War was, of course, declared on 3 September 1939. The YM Harriers club was never reconstituted but, as explained in my paper about Aberdeen AAC, it can be argued that Aberdeen AAC was a successor of the YM Harriers club. (That paper is included within the memorabilia donated to the University.)

As well as giving me much information, Arthur Lobban also gave me some of his athletics memorabilia. I was particularly interested in the medals which he had won while competing in events organised by the North Eastern Harriers Association. These medals are of high quality with three of the medals awarded for wins in individual championship events appearing to be made of silver. Other medals for team events such as the Round the Town Relay appeared to be made of copper but were well made. To my mind, these medals, together with the programmes given to me by Jimmy Adams, reflect favourably on those who were organising athletics competitions for athletes in Aberdeen prior to the Second World War.

Like Jimmy Adams, Arthur Lobban gave me old press cuttings from which much information can be obtained about athletic activities and individual athletes in Aberdeen in years past. I was also given old photographs from both of those men. One of those photographs was taken at the “YMCA Harriers headquarters” in a hut on the river Dee, possibly the hut belonging to the Dee Swimming Club which Arthur Lobban mentioned when he spoke to me. The photograph shows club members getting a “rub down” after a race. Two of those engaged in giving the rub down have towels over their shoulders as did the trainers in the Shire Harriers photographs.

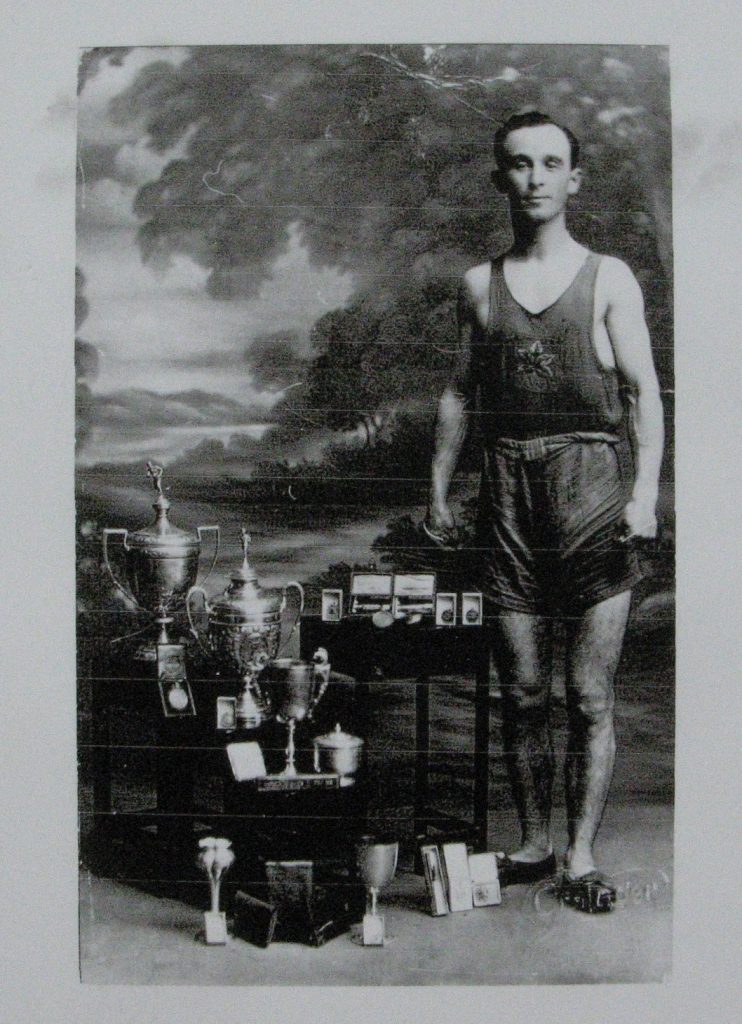

Alex King

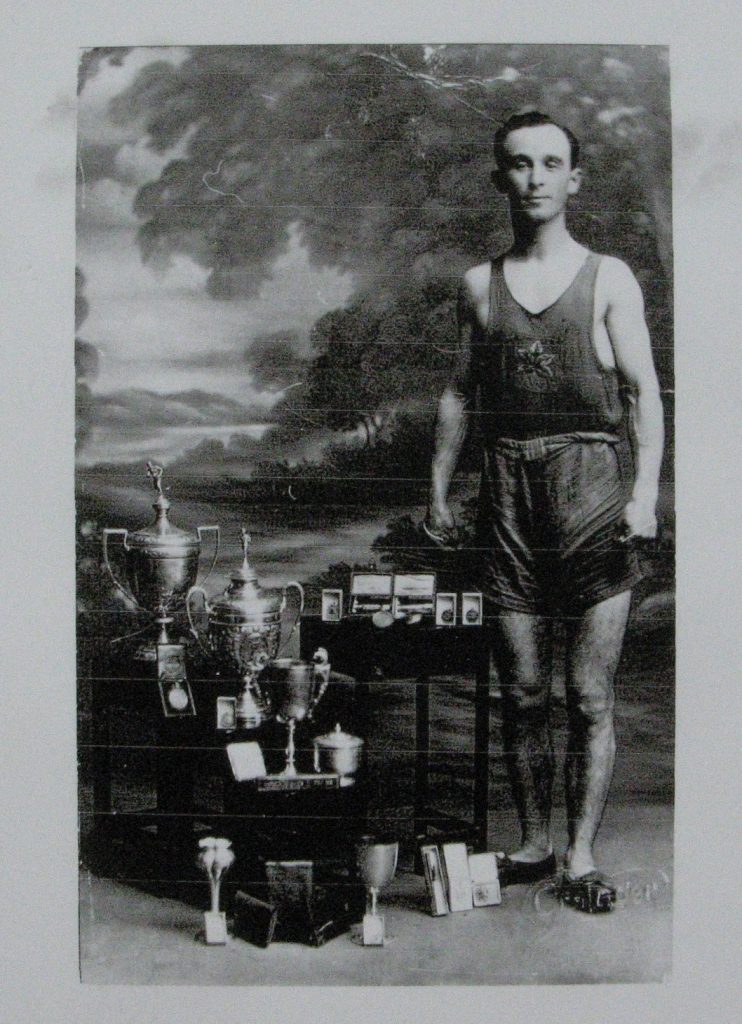

References have been made to Alex King above in connection with his success in winning the early Aberdeen “marathons”. When the Aberdeen marathon was revived in 1979 it was won by the Aberdeen athlete, Graham Laing. Shortly before the second marathon of the modern era, a reporter did a preview of the race and included in his preview photographs of a young Alex King with his trophies beside Graham Laing with his. Being aware of my interest in Alex King, the reporter subsequently gave me a copy of that photograph of Alex King and it is included among the memorabilia which I have donated to the University. Also included is a letter to me from Alex King, a letter in which he outlines his athletics history. Graham Laing, incidentally, went on to win the 1980 Aberdeen marathon in spite of international competition. He later was selected to represent Scotland in the marathon in the 1982 Commonwealth Games.

Robert Miles

Robert Miles was the first secretary of Aberdeen AAC. It was he who gave me information about the public meeting held in 1952 which led to the formation of this new club. Robert Miles also gave me some documents relating to the club which were still in his possession as well as Aberdeen AAC membership cards for the 1954 – 55 and 1955 -56 seasons.

Someone, I cannot be certain who, also gave me a membership card issued by the Aberdeen Y.M.C.A. Harriers. This contains much fascinating information.

For some reason unknown to me Aberdeen AAC ceased to issue membership cards until I became club secretary in 1975. The first of those cards, issued in 1976, reveals that the club was affiliated to the S.A.A.A. the S.W.A.A.A. and the S.C.C.U. and S.W.C.C.U. This demonstrates that the club offered competition to both men and women during both the track and cross country seasons.

ABERDEEN ATHLETICS MEMORABILIA

Hunter Watson January 2016

Introduction

In this paper I provide some more information about the athletics memorabilia that Aberdeen University has kindly agreed to put into its Special Collection. I do this in the hope that the information might encourage some people to look at material lodged there and, perhaps, go on to produce a short history of athletics in the Aberdeen area. Alex Wilson and Colin Youngson have already produced a brief history of the Shire Harriers marathons and that is included within the memorabilia which I have offered to Aberdeen University.

Alex King

In the my preceding paper I made reference to Alex King, winner of three of the Shire Harriers’ marathons, and I mentioned that a letter from him to me was included within the memorabilia. The following are some of the significant points contained within that letter:

He got a bronze medal at the Scottish Olympic Marathon Trial in 1912.

On 26 July 1913 he ran 15 miles at Pittodrie in a time of 1 hour 26 minutes and 36 seconds.

He joined the Canadian army and won the 1 and 5 mile races organised by it in Kent in 1916.

He finished third in a 1500m race at a big international meeting of the Allied Armies in Paris in 1918.

At 60 years of age he ran the mile in 5:42 (This is a superior performance to the 5:23.5 which is the Aberdeen AAC over 60 record for the 1500m.)

Alex King

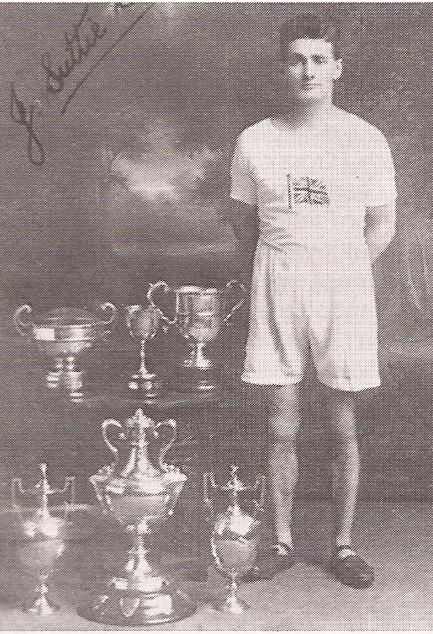

Jimmy Adams

In my previous paper I also made reference to the letters written to me by Jimmy Adams, a former Scottish Internationalist and the first President of Aberdeen AAC. As well as letters, he sent me the bronze SAAA Championship medal which he had been awarded for the high jump in 1921 and the silver medals which he had been awarded for the same event in 1922 and 1923. He also gave me British YMCA National Hexathlon Honours Ribbons which he had obtained in 1920 and 1922. (These were given to YMCA members who had attained the requisite standards in three field events and three track events.) Jimmy Adams also gave me several photographs and press cuttings. He gave me those various items in the expectation that I “would be good enough to preserve them”. Were he alive today then he might be delighted to learn that Aberdeen University is prepared to put all that he gave me into its Special Collection.

Jimmy Adams had been a pupil at Robert Gordon’s College. He left that school in 1911 and found work in the Harbour Treasurers’ Office but found that rather boring so “joined a ship (Deep Sea Tramp)” which took him round much of the world. In 1914 the ship which he was on had an encounter with the German light cruiser, the Emden, and that resulted in Jimmy Adams, and presumably the other crew members, being landed at Pondicherry. (By early September 2014 the Emden was cruising in the Indian Ocean attacking British merchant shipping. However, the captain of the Emden did his best to ensure the safety of the crews of the ships which he attacked and it was common for them either to be put ashore in a neutral port or to be transferred to a non-belligerent ship. If the captain of the Emden had been a less chivalrous person then athletics in Aberdeen might have followed a different path.)

After Jimmy Adams got home from Pondicherry, he joined the navy. According to information about him in a press report, “He was serving as a range-finder with the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in 1914(?) when it was announced in daily orders that anyone interested in athletics would be allowed ashore to train for the fleet championships.” He made known his interest and later won the high jump title in the Fleet championships at Rosyth. In 1918 he was chosen to represent the Grand Fleet against the American Fleet.

When Jimmy Adams was discharged from the navy in April 1919 he settled in Aberdeen with the intention of joining one of the city’s athletic clubs. It was a toss-up as to whether he should join the Shire Harriers or the YMCA Harriers. However, on one occasion he happened to meet Charlie Howie, secretary of the YMCA Club, and Charlie persuaded him to join the YMCA Harriers. (According to Alex King, the Aberdeen YMCA Harriers had been founded in 1912 by Charlie Howie and another man called J.V.E. Barron.)

In one of his many letters to me Jimmy Adams wrote “At that time we had a ‘stripping hut’ in Viewfield Road opposite Rubislaw Quarry … An oil lamp was our only means of lighting.” There was also “a large zinc bath which we filled with water from a tap in the adjoining property. This I may say was for anything from 10 to 30 members to sponge themselves down or wash on their return from a training run … Eventually we had to move from there … and we rented a wooden hut on the banks of the River Dee near the Suspension Bridge (the Wellington Bridge) on the south side. The heating of the water was by the same method and the same bath (was used). First to arrive got the water from the Dee, lit the stove and with fingers crossed away the members went for the usual Road Training Session …” (Among the memorabilia is a photograph of YMCA members in that hut.)

“After 2 or 3 years we (all the YMCA members) transferred to a hut we had erected on a vacant piece of ground which the YM had rented. There we all did our share of making a lovely (by late 1920s standards) cinder track.” That track was to the south of Linksfield Road opposite where the Linksfield Stadium was later built and where the excellent all-weather track is now situated at the Aberdeen Sports Village.

In the same very full letter Jimmy Adams wrote “Prior to the 1914-18 War there were the Aberdeenshire Harriers, the YMCA and, of course, the University Athletic Association. At the end of the War there came a revival of athletics and we had the ‘Shire Harriers, YMCA Harriers, Thistle Harriers, Shamrock Harriers and the Varsity Athletic Club. Eventually, after a brief life, the Shamrock and Thistle Clubs folded up and left the remaining 3 clubs to carry on to the 1939-45 War.” (It should be noted that, according to Arthur Lobban, prior to the 1914-18 War there was also an Argyll Harriers and an Aberdeen and District Harriers Association.)

“When the Corporation built Linksfield Stadium it was really to supply the needs of 2 Junior Football Clubs … as they had lost their ground … called Advocates Park … The old YMCA hut and cinder track was to be taken over for a housing programme so we got the use of Linksfield Stadium on a rental basis.”

“My greatest ever joy was at Stoke when the late Eric Liddell … won the 100, 220 and 440 yards.” In another letter Jimmy Adams stated that Eric Liddell had run those races “in my spikes as he had left his own at the hotel he was staying in when he was competing at the White City grounds”. In this letter Jimmy Adams expressed the opinion that Eric Liddell was the only British athlete to have won 3 races in international competition in one afternoon. Given the circumstances, it is hardly surprising that witnessing Eric Liddell accomplishing that feat is something that Jimmy Adams remembered with particular pleasure.

“As far as Ladies Clubs are concerned, originally the first Ladies Club in Aberdeen was the Aberdeen Ladies Hiking and Athletic Club in the late 1920’s and had, I believe, a sort of affiliation with the Aberdeenshire Harriers Club (unofficially). Then there was I rather think, a breakaway few, by way of some internal trouble who left and started up another Club which was then known as the Bon-Accord Ladies Athletic Club.” (It should be noted that the programme for the 1931 Sports Meeting which was held at Pittodrie on18 July 1931 there were 7 entrants from the Bon-Accord Ladies Athletic Club and 14 entrants from the Aberdeen Hiking and Athletic Club as well as a few entrants for ladies events from neither of those clubs.)

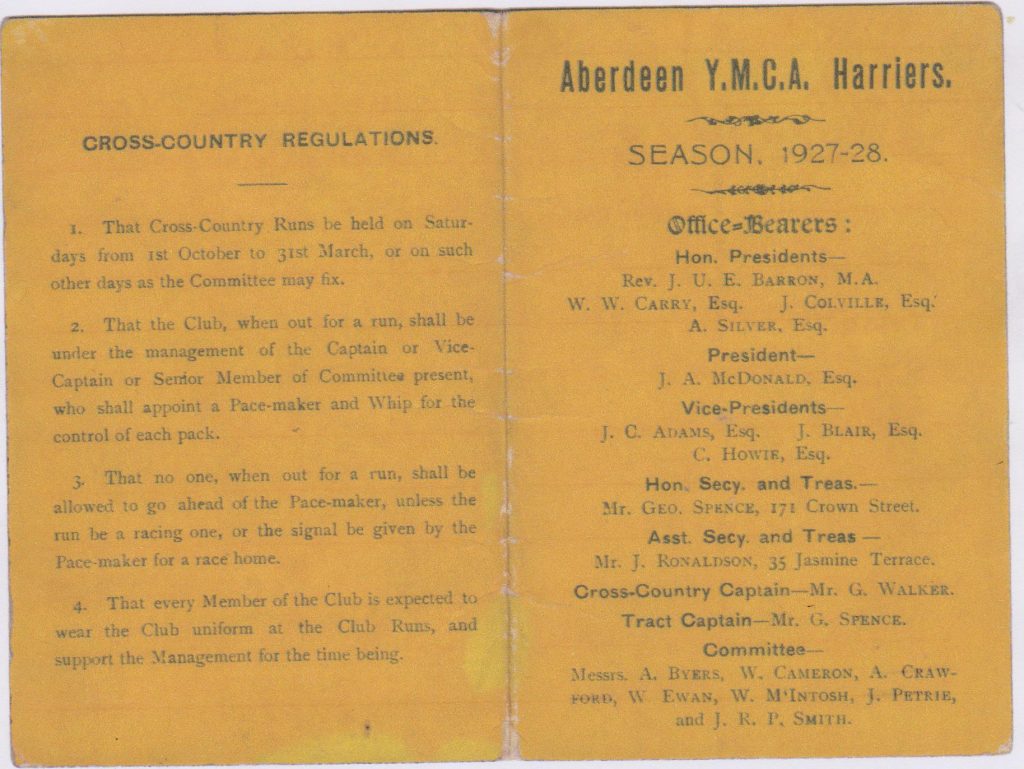

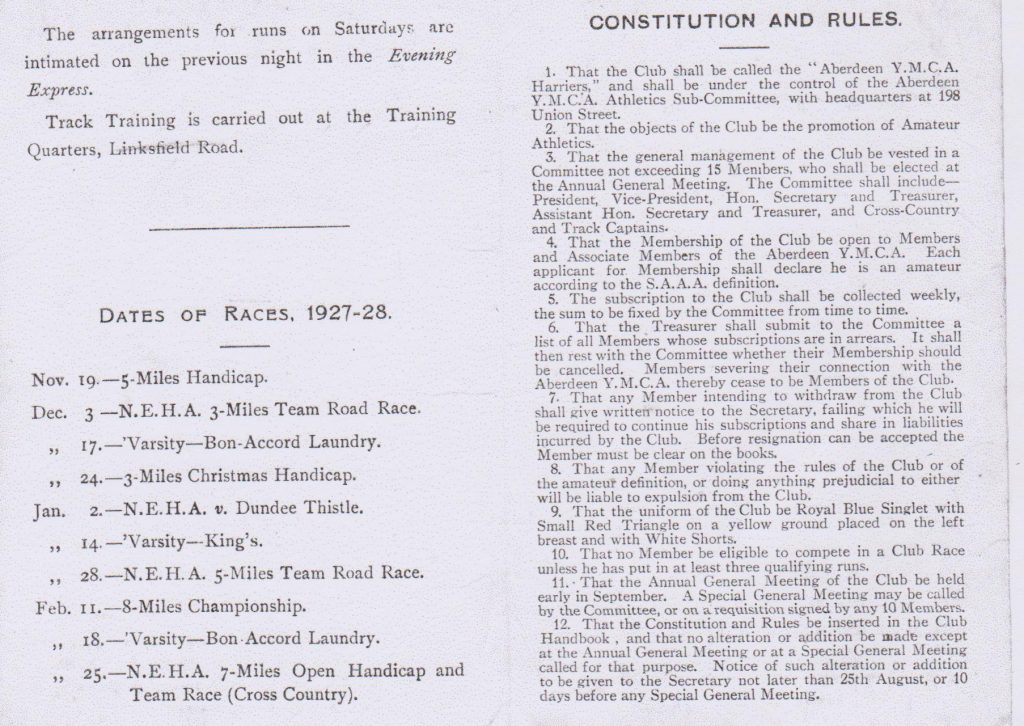

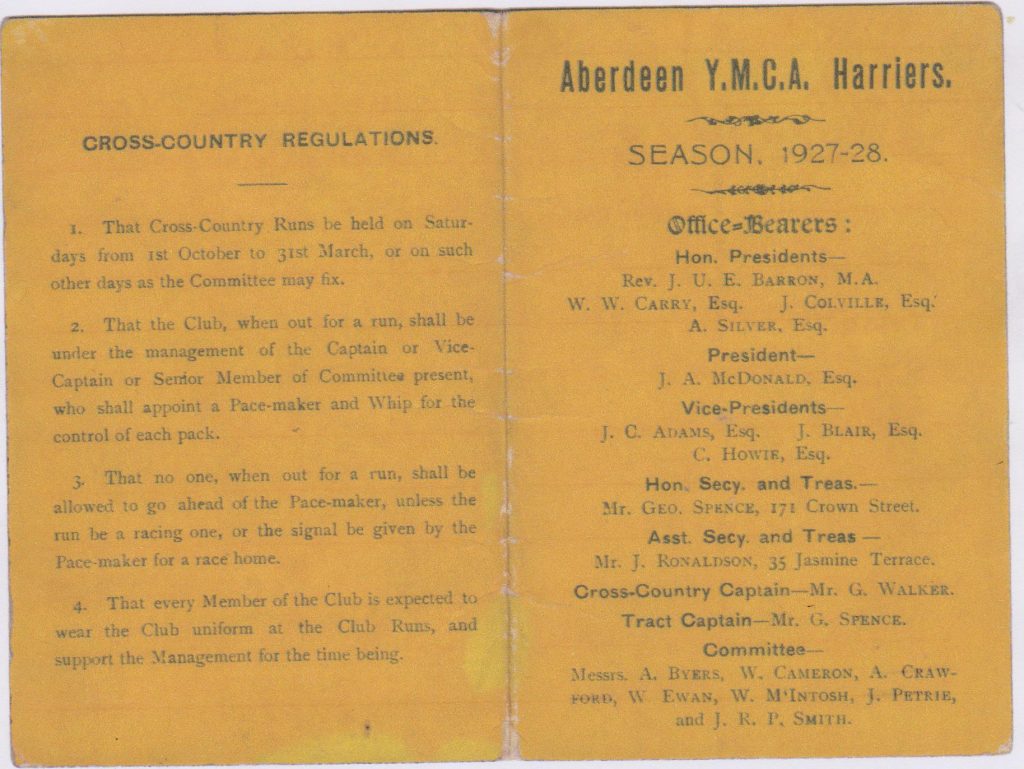

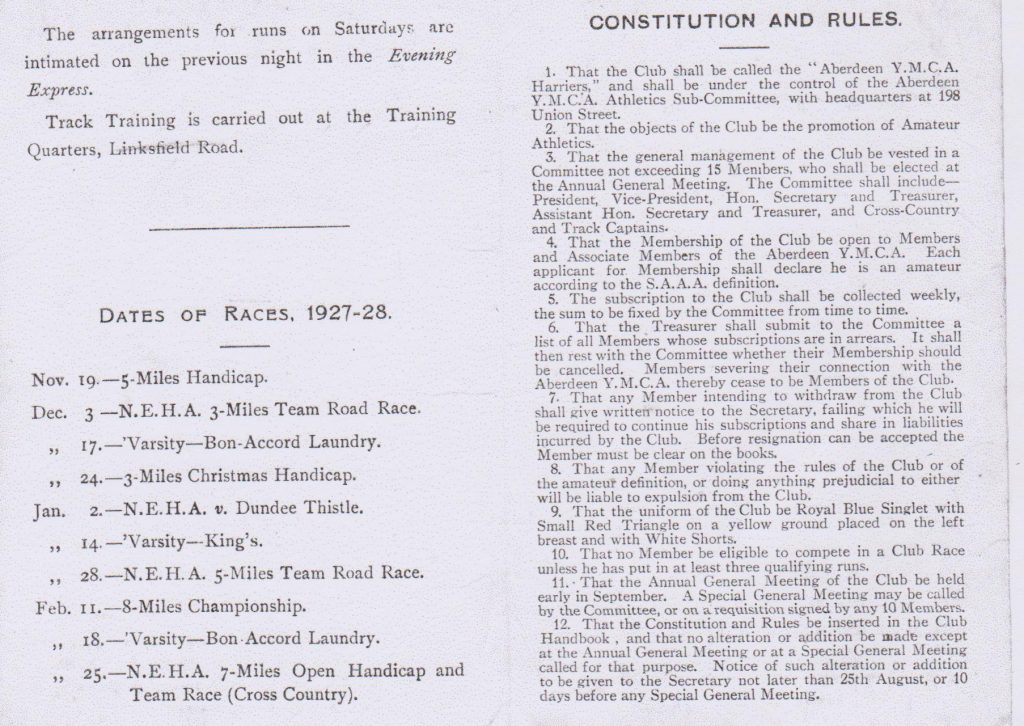

Aberdeen Y.M.C.A. Harriers membership card

I expect that I was given the YMCA Harriers membership card for season 1927-28 by Jim Ronaldson who was the assistant secretary and treasurer of the club for that year. He was one of those whom I visited when seeking information about athletics in Aberdeen in the years preceding the Second World War.

A study of that membership card reveals much of interest. For example, Charlie Howie, a founder of the club, was then one of its Vice-Presidents as was Jimmy Adams. Also of interest may be the following:

The club colours were a Royal Blue Singlet with a Small Red Triangle on a yellow ground placed on the left breast and with White Shorts.

The Constitution of the club stated “That the Club shall be called the ‘Aberdeen Y.M.C.A. Harriers’ and shall be under the control of the Aberdeen Y.M.C.A. Athletics Sub-Committee with headquarters at 198 Union Street”. (Former members of the Aberdeen YM Harriers, including Jimmy Adams, played a major part in establishing Aberdeen AAC in 1952 and it was no doubt for this reason that Aberdeen AAC for several years held its Annual General Meetings in the YMCA premises at 198 Union Street. Indeed, those AGMs were still being held there in 1966 after I became a member of the club.)

The cross country regulations of the YMCA Harriers stipulated that a Pace-maker and a Whip shall be appointed for the control of each pack and, further “That no one, when out for a run, shall be allowed to go ahead of the Pace-maker, unless the run be a racing one, or the signal be given by the Pace-maker for a race home”. (When I joined Edinburgh Eastern Harriers in 1953 that club had no such regulation relating to cross country running. However, at the opening run of each season the various Edinburgh Harrier clubs once met together at the Portobello Baths and the runners divided themselves into a fast and a slow pack, each under the control of a Pace-maker and a Whip. Each year towards the end of the run, members of the fast pack were lined up on the promenade at Portobello and then raced the final half mile or so to the baths where we enjoyed a pleasant swim. The fields over which we ran then are now built up. The same, obviously, is true of many of the fields in which cross country events once took place in Aberdeen. As for the use of Pace-makers and Whips, I doubt whether this would now be appropriate for confined club runs but believe that there could still be a place for them in inter-club runs. It is my opinion that not every inter-club event need be of a competitive nature.)

The programme of events contained in the YMCA membership card reveals that two meetings with the University were to take place from the Bon Accord Laundry. (As can be confirmed from the internet, this laundry had been situated on Abbotswell Road, which had once commonly been called Laundry Brae. This laundry, not Aberdeen’s only one, had been established in 1886.)

The Milne twins

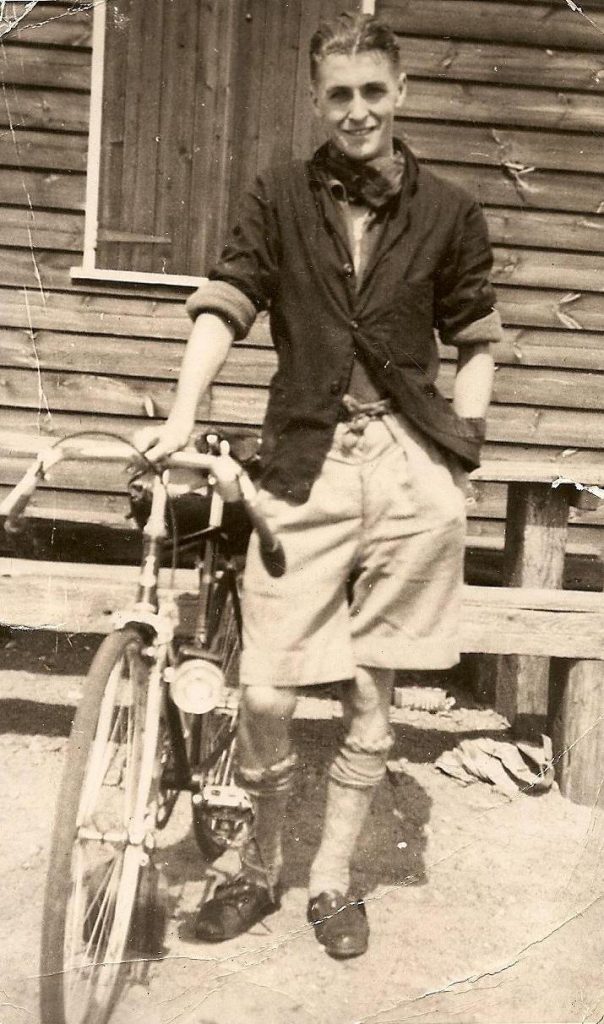

Two of the best runners in the Aberdeen YMCA club in the years immediately preceding the Second World War had been the twins, Alex and George Milne. In a photograph taken of the Aberdeen YMCA team that won the Round-the Town Relay Race in 1938, Alex and George Milne are the two athletes at the back of the group.

Alex Milne was an athlete whose performances would still be considered of high quality by modern standards. Evidence of this is contained in the press report which noted that Alex had set a course record of 25 minutes 31 seconds for the 5 mile fourth stage of the Round-the-Town relay race. The fact that the stage included a significant hill makes his performance all the more impressive. The course was described in the press as follows: “Out Menzies Road to Kirk o’ Nigg, down Abbotswell Road and over Bridge of Dee and in Riverside Road to Victoria Bridge to the fifth take-over.” George Milne, for his part, broke the record for the second stage by a margin of 37 seconds.

Another press report stated that “By his victory in the North Eastern Harriers’ Association’s five miles cross country championship this afternoon, Alex. Milne, Y.M.C.A., is the first man in the North-east of Scotland who has won four successive individual championships over this distance”. In that event George Milne had finished in third position not far behind his brother.

In 1939 the Milne twins made the long journey south to Hawick to match themselves against the best cross country runners in the East of Scotland. In that race, the Eastern District Cross Country Championships, George finished in a creditable fourth position with Alex in seventh. Unfortunately the Aberdeen YMCA Harriers were unable to send a team to this distant event. It is unlikely that they would have won it, but it would have been interesting to find out how they would have compared with other East of Scotland clubs. Many years later, Aberdeen AAC proved that it could comfortably hold its own with clubs from elsewhere in Scotland.

Influences from Edinburgh

As the documentation demonstrates, after I was elected to the Committee of Aberdeen AAC in 1966 I organised a jumble sale in order to raise funds for the club. I also organised a schoolboys cross country event in order to attract boys into the club. Both of those ideas were based upon what Edinburgh Eastern Harriers had done when I was a member of that club. I was unsuccessful, however, in persuading the then Committee of Aberdeen AAC to produce a membership card along the lines of the Edinburgh Eastern Harriers’ card even although I brought one along to a committee meeting.

When I later became club secretary of Aberdeen AAC I did not attempt to organise another jumble sale to raise funds: other means of fund-raising were adopted. I did, however, organise cross country races for primary school children, both boys and girls, in order to attract youngsters into the club. I also, with the full agreement of the club committee, arranged that membership cards were produced. These resembled the Edinburgh Eastern Harriers’ membership cards in that on the front cover they showed when the club was founded and, inside, they contained club records. Later (as a result of a suggestion by Edwin Reid, one of the excellent Aberdeen AAC presidents) within the membership card there was included the club constitution. The Aberdeen AAC membership card, however, contained no information about fixtures. Instead members of Aberdeen AAC, during my time as secretary, were issued with a programme detailing cross country events at the start of each cross country season and a programme detailing track and field events at the start of each track season.

The format of the club membership card remained basically unchanged until at least 2003. Sometime thereafter it was decided to issue members with a small laminated card which gave only the name of the member, the membership number of the member, the name of the membership secretary and the website address of Aberdeen AAC. That was a sensible thing to do since members already received a yearbook which contained club records. To that has been added the club constitution and, each year, an up-to-date list of club office bearers and ordinary committee members. That club year book is now a publication of which Aberdeen AAC can be rightly proud. For example, the 2015 Yearbook contains

Coloured photographs of members

Club Records for all age groups

Highlights of the club’s 2013-14 and 2014 seasons

Club all-time lists of senior Scottish champions

All the Club’s major games representatives

Club all-time indoor rankings – senior events

Club indoor records for all age groups

Club all-time top 20 lists – senior events

Club all-time top 10 lists – U 20, U17 & U15 events

Club all-time top 10 lists – veteran men and women

2014 top 5 rankings for all age groups.

Anyone studying those yearbooks will be impressed by the standard of the performances of members of Aberdeen AAC, by the range of age groups and events for which the club caters, by the dedication of Denis Shepherd and others who compile the data and, of course, by all those who by their efforts ensure that the club continues to provide the coaching and competition which members rightly expect.

ATHLETICS IN ABERDEEN

W Hunter Watson January 2016

Introduction

This paper follows on from my three previous papers on the topic of athletics in Aberdeen. It corrects and clarifies some of what was contained in those. In spite of its title, the paper does not confine itself exclusively to athletics nor to Aberdeen: it contains a few other snippets of information which I came across in the course of my research, snippets which might be of interest to some.

I am well aware that my papers have hardly scratched the surface of the topic of athletics in Aberdeen. I have not, for example, written about Aberdeen University athletes, not even about James Soutter or Quita Shivas (really Isobel Shivas) even though both of these athletes gained Olympic selection. Hopefully others will eventually fill in some of the gaps.

Jimmy Adams

In my paper entitled “Aberdeen AAC” I wrongly stated that Jimmy Adams was the secretary of the North East Harriers Association. However, as noted in my paper entitled “Aberdeen Athletics Memorabilia” he was, in fact, the Vice President of that Association. (This information was contained in one of the letters written to me by Jimmy Adams.) Further, as can be verified by studying the medals given to me by Arthur Lobban, the correct title of that Association was the North Eastern Harriers Association.

In a letter which made reference to the hut on Viewfeld Road from which the YMCA Harriers trained in the early 1920s, Jimmy Adams wrote “We had our pennyworth in the tram car to Bayview (the terminus) and walked the rest of the way”. Thus at that time tramcars did not go as far as Hazlehead Park. That they eventually did so is proved by a photograph in the book entitled “Aberdeen’s trams 1874-1958”. The photograph in question shows a tramcar fitted with a snowplough clearing the tracks to Hazlehead in March 1955. That book about Aberdeen’s trams noted that “By 1920 the Corporation Tramways carried more than 49 million passengers a year, and although the Suburban Tramways were abandoned in 1927, the Corporation Tramways continued to develop. In 1946 69 million passengers were carried by tram and 39 million by bus”. Tramcars were a popular means of transport, but they were liable to hold up traffic somewhat and that might have been one of the reasons why a decision was made to remove tramcars from the streets of Aberdeen and several other cities including Edinburgh. (The latter city, at great expense, has begun to reintroduce them.)

Women’s athletics

In my paper entitled “Aberdeen Athletics Memorabilia” I stated that in 1953 I had joined an Edinburgh club called Edinburgh Eastern Harriers which was similar to the pre-war Harrier clubs in Aberdeen in that it did not cater for women. I further stated that on 27 March 1961 there was a joint General Meeting of three of the Edinburgh Harrier Clubs, namely Edinburgh Harriers, Edinburgh Northern Harriers and Edinburgh Eastern Harriers. Those present agreed that those three clubs should amalgamate to form a new club to be called Edinburgh Athletic Club. I observed that this new club was to be affiliated to the S.A.A.A. and the N.C.C.U. but not to the corresponding women’s organisations. I wondered whether each of the three clubs that had come together to form Edinburgh AC might have catered only for men and boys and whether, initially, Edinburgh AC might also have been without women as members. As a result of enquiries which I have made, I have now established that one of those three clubs, namely Edinburgh Harriers, did accept women as members. Beyond reasonable doubt, Edinburgh AC would have done so also from its inception.

During the course of my research I discovered that the Scottish Women’s Amateur Athletic Association (the S.W.A.A.A.) had been established only in 1931. According to the information supplied to me by Jimmy Adams, the Aberdeen Ladies Hiking and Athletic Club had been established in Aberdeen by the late nineteen twenties, and hence before the establishment of the S.W.A.A.A.. It is possible, therefore, that this Aberdeen club was one of the first in Scotland to cater for women who wished to take part in athletics.

While on the internet to obtain information about the S.W.A.A.A., I noticed that it contained a list of Scottish women’s best performances in athletic events. I was intrigued to observe that the first of the best performances of Scottish women for the mile was credited to a member of the Aberdeen Bon-Accord Ladies Athletic Club, namely Agnes Milne. She is credited with having run a mile in a time of 5:45.0 on in Aberdeen on 2 May 1931. This was presumably at an open meeting organised by Aberdeen University since the Athletic Sports Meeting at Pittodrie was held in July. It should be noted that in a letter to me, Alex King credited Alice Milne with a faster time, namely 5:20, but he does not specify when she achieved that performance. I suspect that she did so before the S.W.A.A.A. was established and before, therefore, that organisation began to compile lists of Scottish women’s best performances. It should be further noted that a time of 5:20 for the mile is a superior performance to a time of 5 minutes for the 1500m. Although 5 minutes for the 1500m is far short of current international standards, most managers of women’s club teams today would be delighted to have available for selection someone who was as good a middle distance runner as was Alice Milne all those years ago. One wonders what she might have achieved on a modern track with modern training methods and a good diet.

![1929 Aberdeenshire Harriers Marathon E[1].G. Marshall (cropped)](http://www.anentscottishrunning.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/1929-Aberdeenshire-Harriers-Marathon-E1.G.-Marshall-cropped-1024x785.jpg)