Bill’s publisher describes his journalistic career as follows “During twenty years in journalism he covered a broad spectrum of news and of sport…..Athletics, Badminton, Canoeing, Curling, Cycling, Gymnastics, Judo, Mountain running, Mountain biking, Netball, Orienteering, Rowing, Skating, Snow sport, Squash, Swimming, Tennis, Triathlon, Wrestling, many to world championship level, plus on occasion basketball, boxing, football, golf, pentathlon, rugby and show jumping.

He supplied material to a large number of outlets including

*BBC Radio, *Belfast Telegraph, *Birmingham Post, * Dundee Courier,

*Daily Mail, * Daily Express, *Guardian, *Glasgow Herald (+Sunday), Independent,

* Irish Independent, *Irish Radio, *Irish Times, *Mirror,

* Newcastle Chronicle and Sun, *News of the World, *Aberdeen Press and Journal,

* Daily Record, * Scotland on Sunday, * Scotsman, *Sun,

* Telegraph (+ Sunday), *The Times (+Sunday), * Western Mail

plus newspapers and press agencies in Australia, Canada, Iceland, Finland, France, New Zealand, Spain,

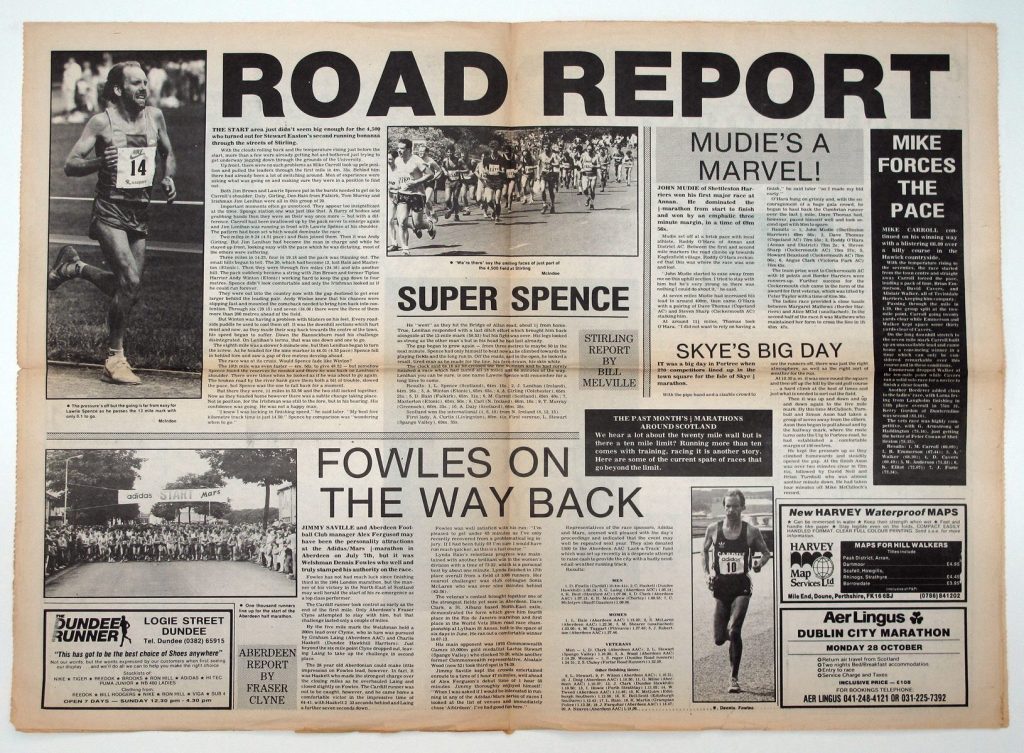

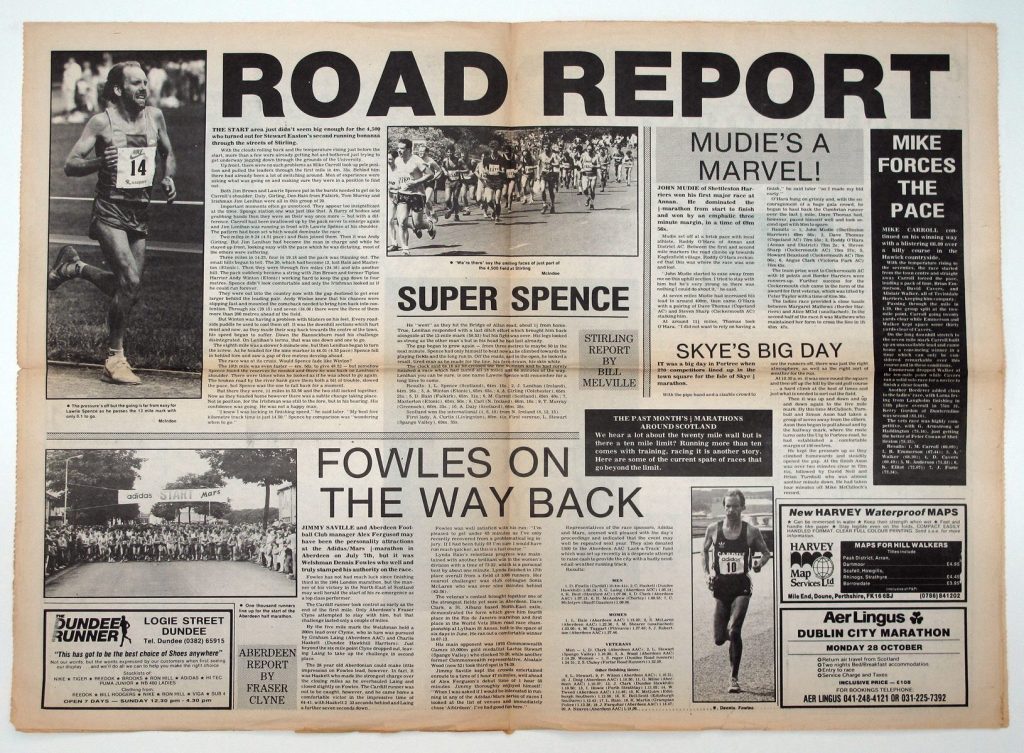

That is some list – and is probably not at all comprehensive. In the UK: from Aberdeen to Bristol and London via Newcastle and Birmingham and across the Irish Sea. In the wider world from Iceland in the North to New Zealand in the south. Each paper had different requirements, different deadlines and different ways of dealing with the same facts. To do all that must have been a daunting job. You can also add in the magazine work – Ron Hill produced a magazine that started out as ‘Jogging’ but became ‘Running – Bill wrote for it too, editing the Scottish pages it contained. And then there was his own Scottish Running magazine. There was also some writing away from the sports journalism altogether. For instance, His script for the documentary drama video, The Two Way Split, won an award.

“Journalism was my second career. I started writing away back when I was a college boy and tried, but failed very early, to get a newspaper job. I got an interview for one of the Scottish nationals but my interview didn’t go well. I thought I was chatting to some minor player in personnel, waiting, as I thought, for my career deciding get together with the editor. But that was never on the agenda. This was my interview. Suddenly I found myself standing, surprised if not shocked, outside the front door again, my chances, like the interview, blown. I wrote occasional pieces for magazines and papers in the years that followed and did a fair amount of small bit reporting on orienteering. I was taking part in the sport and found it was getting nil press coverage. I thought I should do something about this. To my surprise, I found myself getting paid for my “work”.

I still meet up with familiar phone boxes across Scotland. One or other of them would be my office of the day after an event. There, covered with sweat from my run, I would stand notebook in hand, phone pinned to my ear, while I dictated my brief report along with the basic results, to copy takers in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow. In hot summer sun these phone boxes were torture chambers.”

The story about the phone boxes rings true: several reporters have similar stories to tell. It was a time before mobile phones and first man at the phone box was on to a winner.

Colin Shields tells of leaving the stadium, running down the street and, finding a house with a phone connection, ringing the bell, asking if he could use the phone, promising to pay the cost of the call, and getting his story in that way. Even in stadiums with one or even two public phones, club members who had said they would phone home when they were leaving, found that the telephones were hogged by a reporter phoning in detailed results or copy to his employer.

We have already seen the extent of Bill’s involvement in the sport as a competitor and he had been involved in organisation and committee work but how did the reporting come into the equation? Bill himself describes the move into journalism from teaching and speaks of some of the highlights from his many years in that profession. He says:

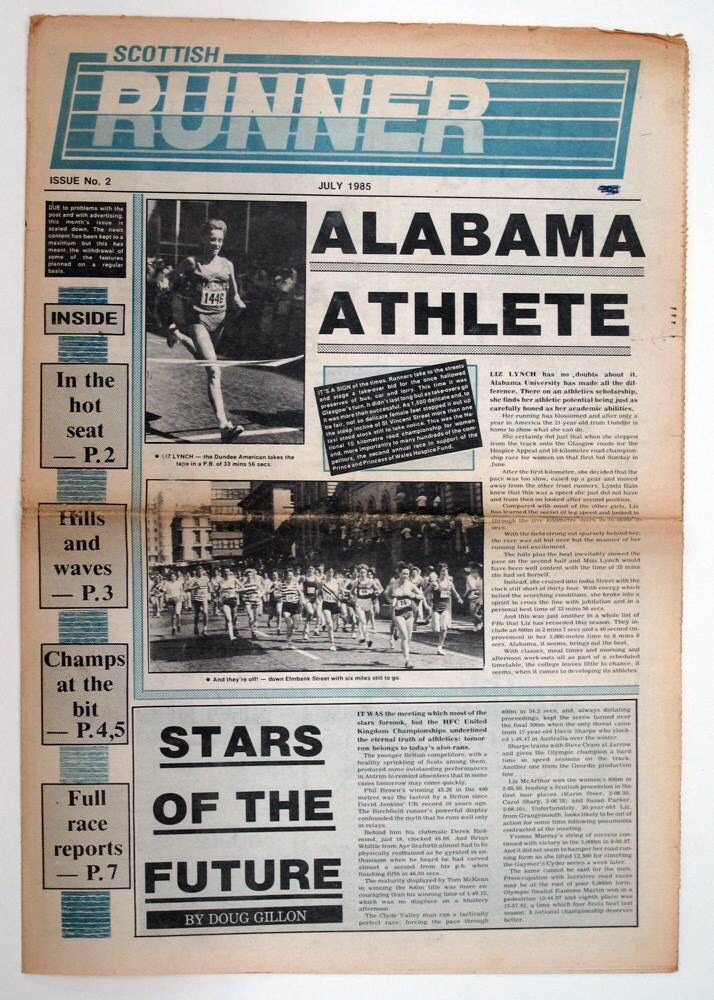

“My move into full time writing came around ten years later. I gave up teaching and went out on my own. I got in six months of practice when I produced my own newspaper, Scottish Runner, using a £2000 government grant. The shed in my Ayrshire garden was my office. It had bats in the roof panelling, I remember. Amongst a number of contacts I used were photographer Graham Macindoe and Doug Gillon. The grant ran out after six months and Scottish went out of business. But I had learned a lot in the time about interviewing, newspaper editing and production and all the time I was fielding bits and pieces to any newspaper I thought might be interested. And I was writing the Scottish section in Ron Hill’s Running magazine. There was no going back.”

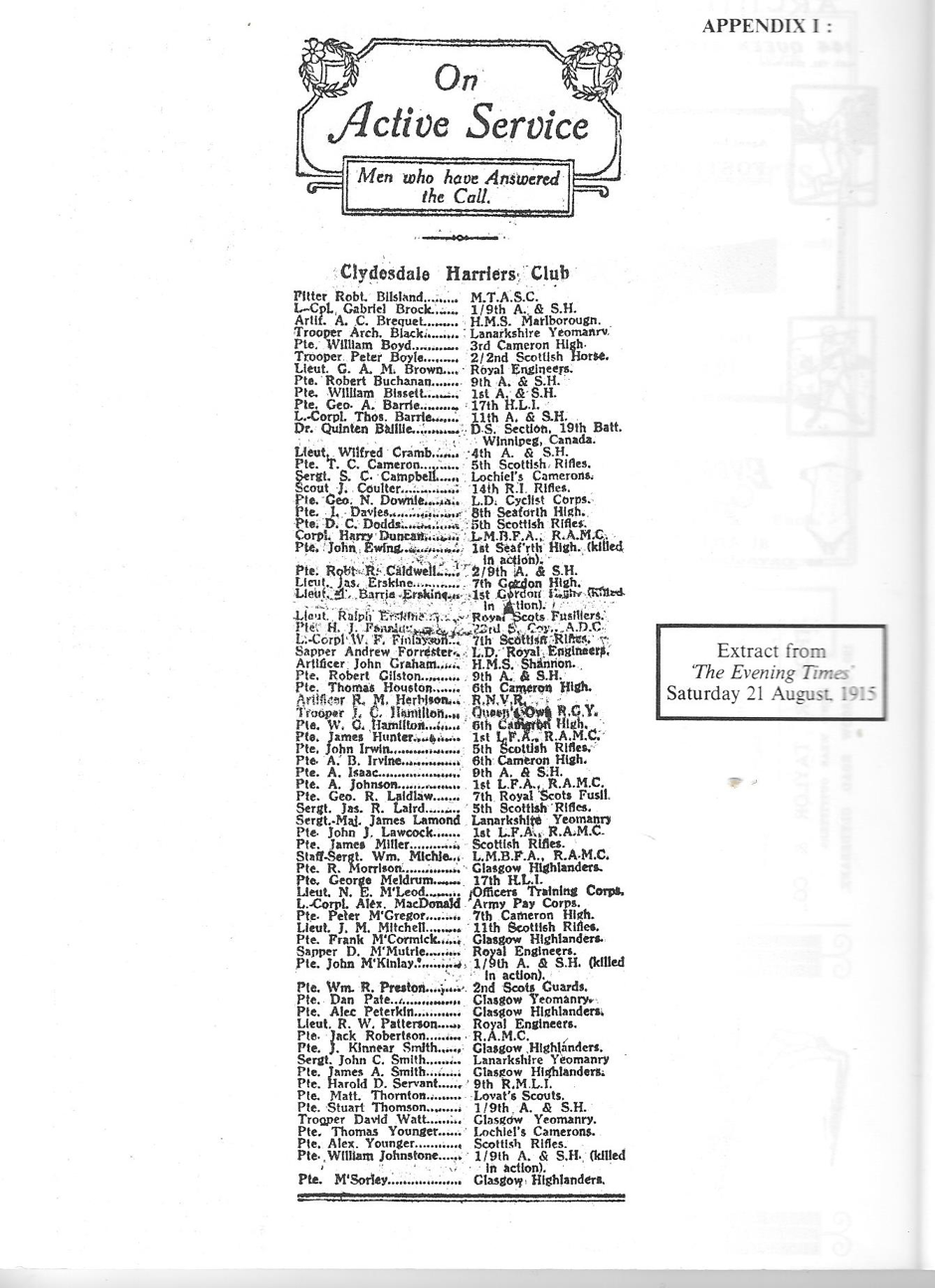

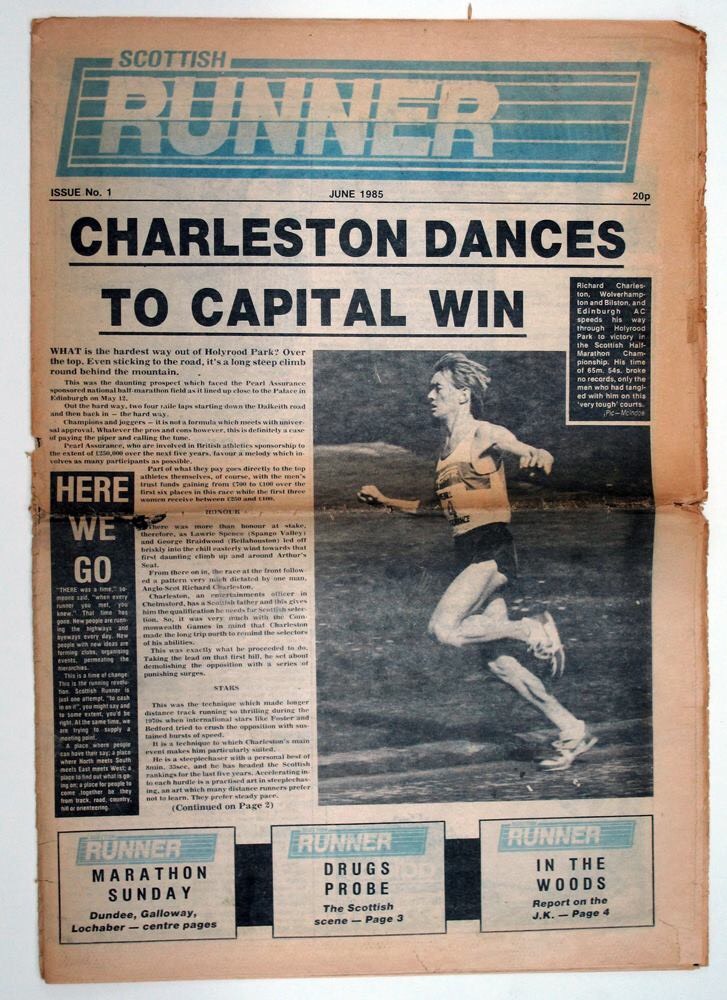

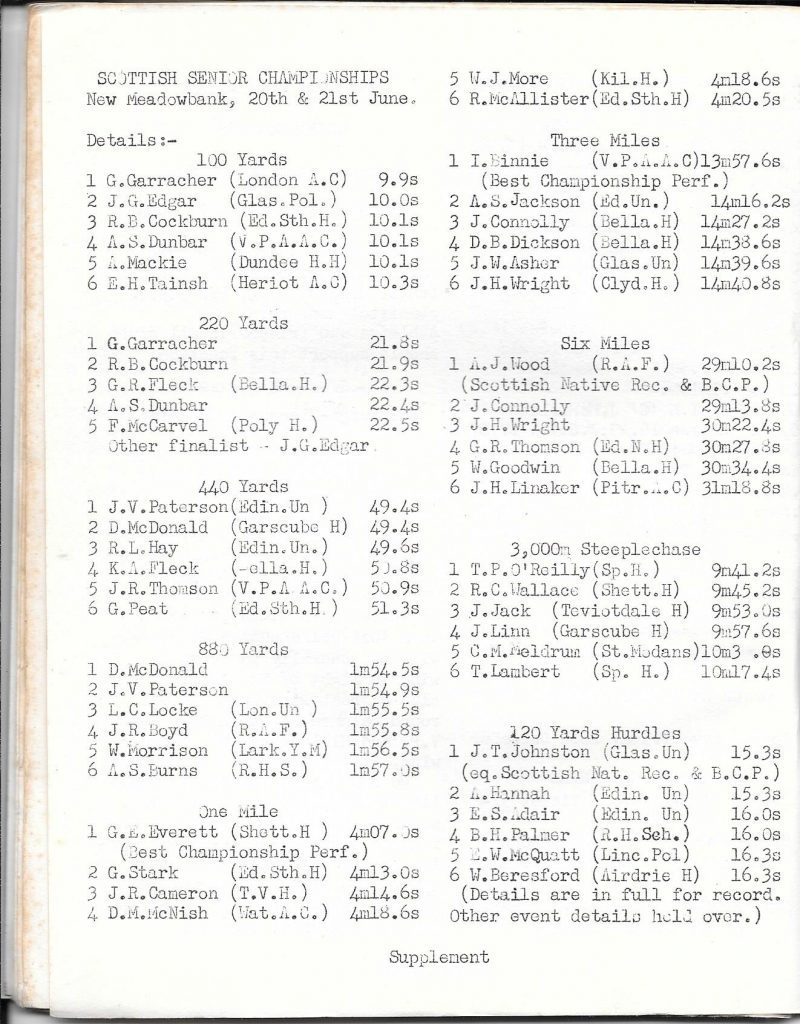

Scottish Runner, Number 1, June 1985

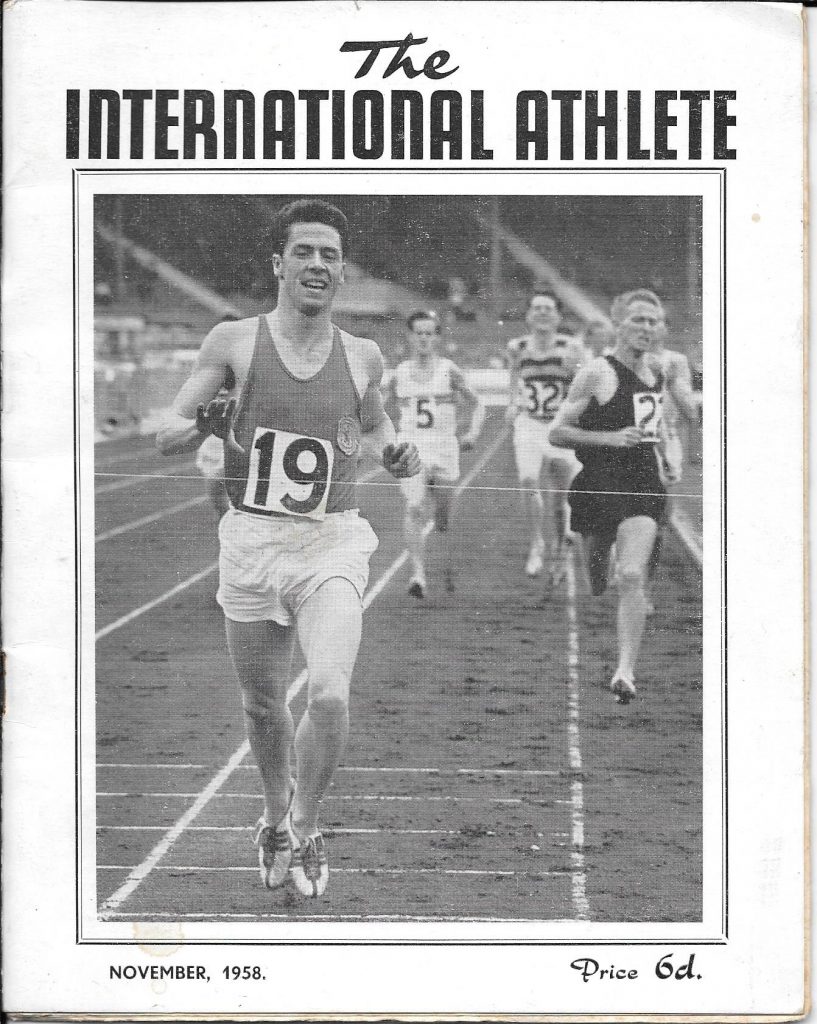

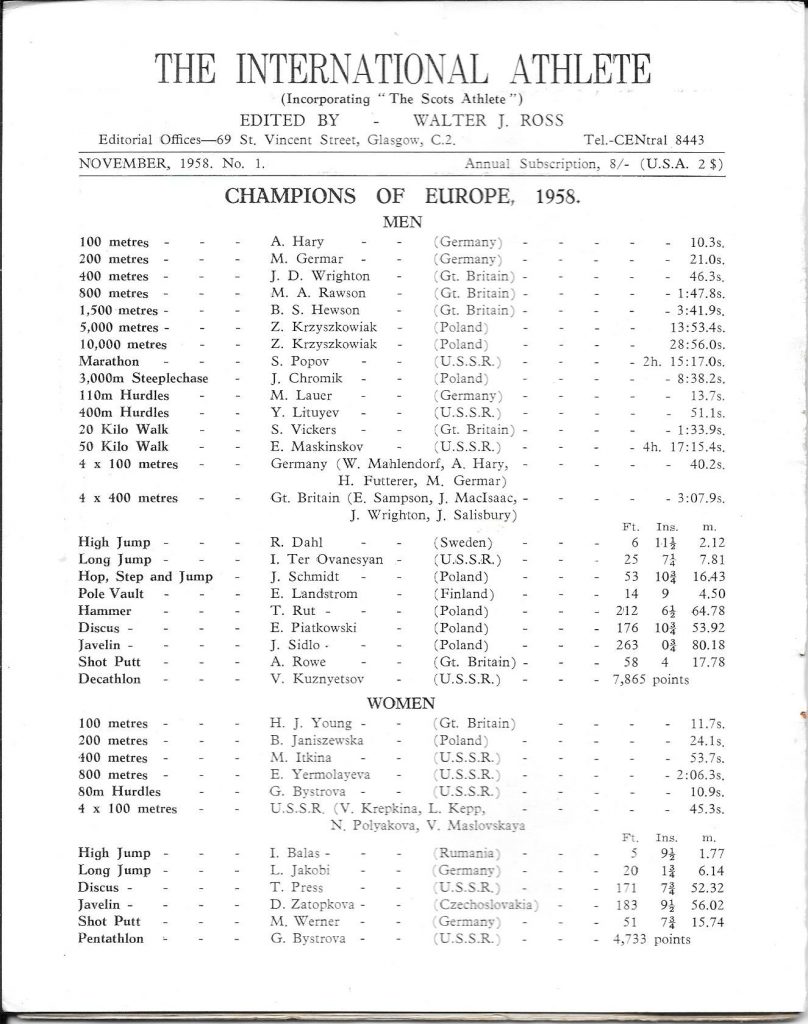

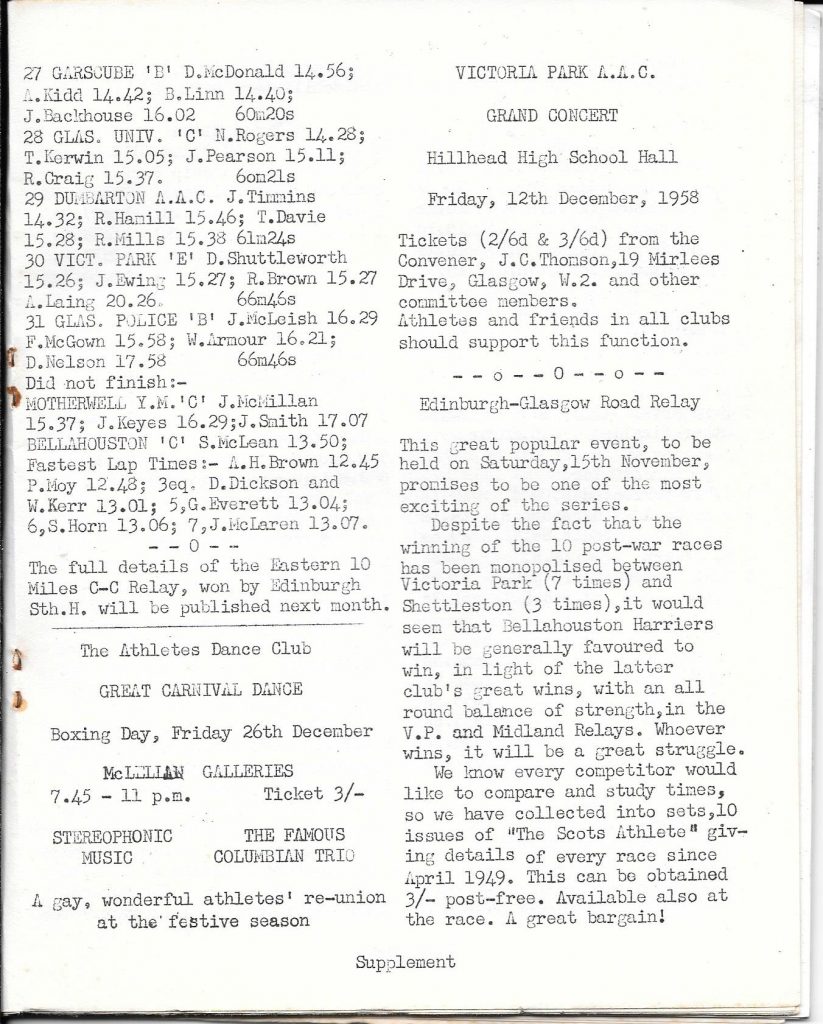

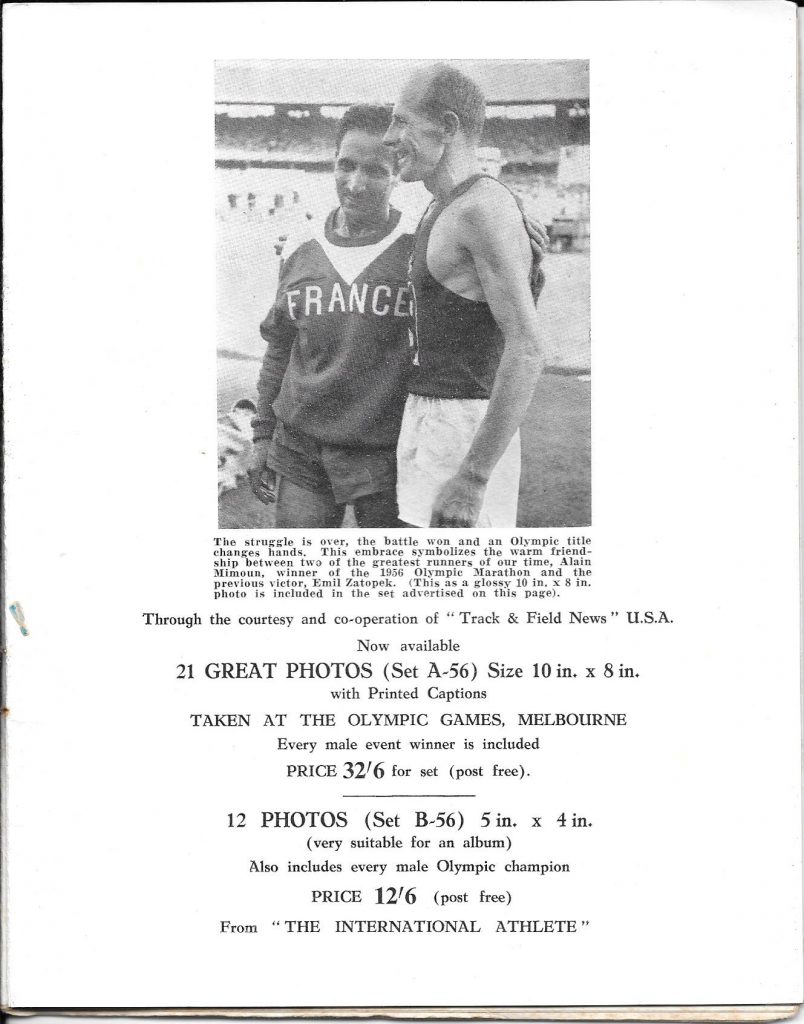

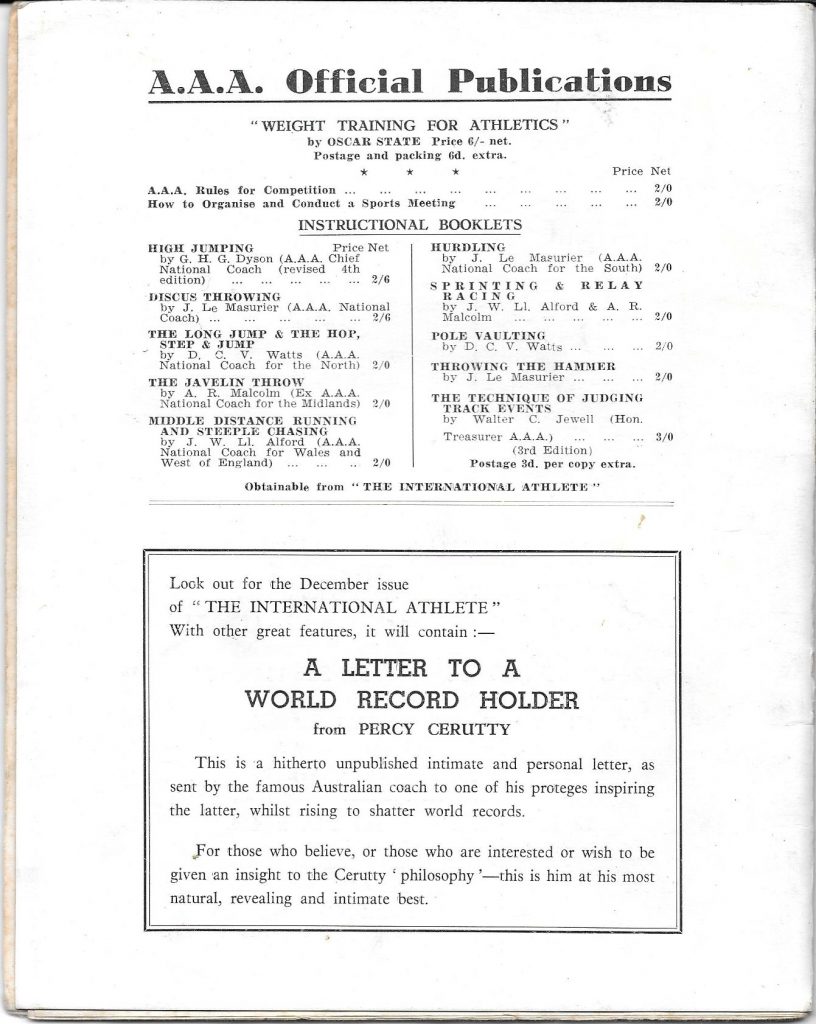

When Bill says it was a newspaper, that was a fair description. Not glossy paper, not printer paper but newsprint. It was very professionally laid out and made good reading. Scottish athletics magazines and papers frequently appear and since the end of the war in 1945, there had been the ‘Scots Athlete’ and the ‘International Athlete’ by Walter Ross in Glasgow covering the years 1946 to the mid 1960’s, and then ‘Athletics in Scotland’ by George Sutherland in the 1970’s. It is a very hard market to break into as was proved by the ‘Scots Athlete’ which was professionally produced with many photographs, a colour cover and just about every Scottish race, domestic and international, reported on. It didn’t make money – rather the reverse. Another example of how difficult it was is shown by way of the “Scotland’s Runner” monthly. Immediately after Bill’s venture, “!Scotland’s Runner” appeared. It was produced by a top class team of professional journalists with lots of race results, articles on athletics topice, letters pages, several results pages every month and interviews with current and former champions. Produced in full colour, it lasted from 1986 to 1993 before it stopped publication. Bill’s was a very good publication but it was fighting its corner in a tough neighbourhood. His reference above to the help that he received from Doug Gillon and Graham MacIndoe is notable because they both speak well of him. Graham is a really top class photographer whose pictures were published in all the very best athletic magazines including the athletics ‘Bible’, Athletics Weekly. Doug wrote for the ‘Glasgow Herald’ and his reports were always meticulously written. He indicates that the traffic was not all one way when he says,

“I knew Bill and his wife Kath for many years during which he worked as a freelance sportswriter, filing to many national and regional papers, including The Herald when I worked there. He was an affable and most helpful and diligent colleague, always prepared to give information and advice. I’d consult him often when he was at a track or cross-country event which logistics had prevented me from attending, and we would swap information.” He went a bit further when speaking on the telephone describing Bill as helpful and friendly adding that Bill was one of a few colleagues that he would contact in this was because he knew that Bill was always scrupulously accurate.

Bill continues:

Operating as an independent is a hard way to make a living. To do it covering just athletics and orienteering in the UK was impossible. So to make ends meet I covered everything from the action in Kilmarnock Sheriff Court to results from the midweek Irvine road race. Court coverage certainly concentrated the mind on getting the facts straight. I was in court when the editor of the Daily Record was called before the judge for a contempt hearing. A sub-editor’s bid to give a catchy headline part way through a murder trial was deemed to pre-empt the jury’s decision. The editor got off with a warning. I could do without that sort fame. Write the story rather than become the story is a good guideline in journalism.

Working as an independent in any field, running your own business, tones up the initiative. If I wanted to make money I had to both pick a market and diversify. I opted for sport. It has lots of stories happening every day. I covered any that I could search out and I could use to raise a spark of “sports desk” interest. In my time I covered everything in the sporting alphabet from badminton to weight lifting. I went to major or national championships in badminton, curling, rowing, cycling, judo, swimming, tennis, and triathlon as well as athletics and orienteering.

I sold a preview piece to the Independent on a largely unheard of Graeme Obree and his home built bike before his first British championships win that same weekend. The same London paper took a piece on the Carnethy 5 Hills race season opener. I travelled to work across Europe – Bulgaria, Italy, France, Sweden, Norway, Spain, Germany, Czech Republic, and Portugal as well as to S. Korea, and Canada. I was fielding material to papers across Britain, and Ireland as well as to Canada, Australia, Iceland, Scandinavia and Spain. “

In my time I supplied regular but not continuous Scottish athletics coverage to the Record, Daily Express, Daily Mail and the Times.

(Curling coverage for the Times was one of my major earners.) Often I picked minor championships that I knew the newspaper regulars would not be covering – World Student Games say or World Junior Athletics Championships, catching many athletes at the start of what blossomed into glittering careers…….. Jon Ridgeon in Zagreb, Haile Gebrsellassie in Seoul, Steve Backley in Sudbury, Ontario, sprinters Darren Campbell, Christian Malcolm and Trinidad’s Ato Boldon.

If you say the previous two paragraphs quickly, it seems like a lot of travelling, if you read it slowly you see just how much in detail. All over Europe ( was there a country not included? There was France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Sweden and much of Eastern Europe), Asia, Africa and North America. As a freelance, these events had to pay for themselves and so Bill covered many of the minority sports at the same Games or Championships. As he says there was interviewing star performers, often informally: this also sounds quite glamorous but there are times when even the best athletes are on a ‘down day’ and not feeling friendly, and for the reporter not all athletes approached would be as friendly as those quoted. It was serious work. And then there was the work to be done at home.

“Minor sporting events also produced some major sporting moments. I headlined a young Graham Williamson in a Radio Clyde piece when he won a Greenock Highland Games mile. I can’t recollect how fast he ran but I do remember he had breathtaking style. I was in the Kelvin Hall in 1990 when a next to unknown Ian Hamer ran a more or less solo 3000m in close to 7m 55s to win the Scottish Universities Indoor title. By March he was in the British team.

Journalism gave me the chance to visit a range of sporting events, meet a lot of interesting sports people and interview some of the famous. A shy Zola Budd competing unexpectedly at the same meet in North London where I was reporting on the Scottish women’s team; the then Liz Lynch who was running there that same day; Linford Christie, who stopped at my behest as he was leaving the Kelvin Hall to answer a few questions. I was late but I needed a quote or two for a news agency piece. He was not only helpful but unhurried and gracious with it. The list could go on and on.

And there were the hundreds of less well known sports people who willingly gave me of their time. With few exceptions they, the great and the not so great, treated me with friendliness and respect. On my part I considered it a privilege to speak to them. It was one of the perks that came my way because, and only because, I was a journalist and I never forgot that.”

I would suggest that any journalist would get the success he does, or not, because of his own manner and approach. Anyone I have spoken to, and both of those quoted here, speak of Bill’s manner and his knowledge of sport which would play no small part in any success he had. There are journalists and reporters that we have all met who came across as anything but pleasant

Another of his friends, colleague Sandy Sutherland, says.

“He was certainly a do-er..he ran and wrote and announced and publicised the sport he loved or the sports he loved if you count orienteering as separate as they certainly would! Much of what he did was a service for the sport and he was often press officer for events I attended in a professional capacity He rolled his sleeves up and obtained the result sheets for others, unlike some of the present generation who are solely interested in getting their story out BEFORE the few journos who are left get their turn!”

Sandy draws our attention not only to Bill’s work ethic, but also to his work as a Press Officer at Scottish Championship events – where he was often also one of the best informed announcers around. As he said on the previous page, “I was heavily involved with Irvine AC by that time, represented the club at the West District Committee meetings for some years and helping Jim Young and his organising squad at many of the local races. ” Where did this lead?

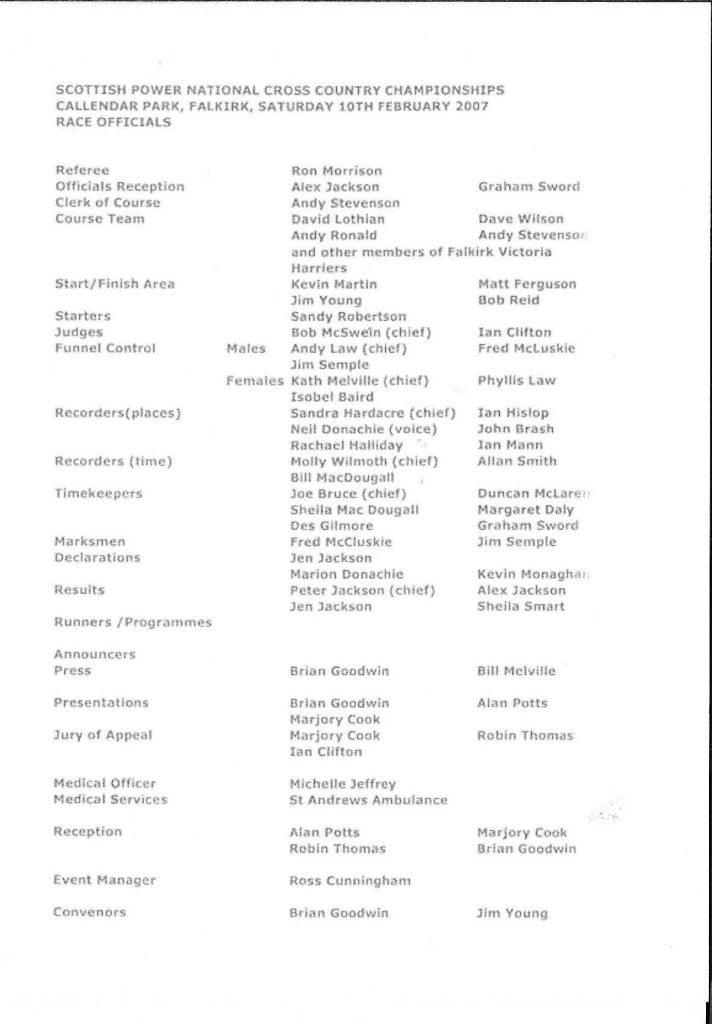

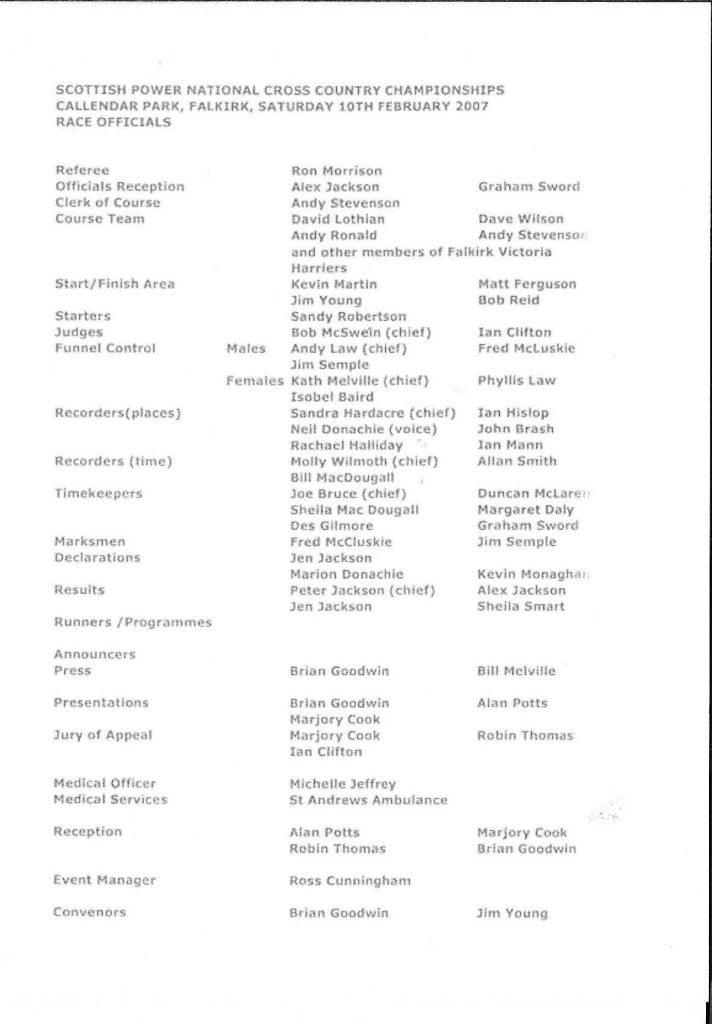

For many years, 1980 to 2010) he was Press Officer or Announcer at the Scottish National Cross Country Championships covering events in Glasgow, Dundee and Hawick but mostly at the Irvine Beach Park venue. In fact he was a member of the Organising Committee for the NCCU Championships, and from 1980 to 2010 with a few exceptions, was either announcer or press officer at the National Championships. In SCCU Centenary Year, Bill was Press Liaison Officer with Colin Shields, but surely his busiest day was in 1982 when he was Clerk of the Course and Press Officer as well as having been a member of the Organising Committee. There were family occasions too as In 1992 when Bill doubled up as Announcer with Alex Naylor plus Press Officer with Kath Melville as Assistant Press Officer. He went on working at the National Championships until well into the 21st Century.

The organisation at national level over the years was noteworthy and many would have been content to count that as their major contribution to the sport. Bill however was using his organisational talents in the sport of orienteering. A member of Tayside Orienteers. he attended many Annual General Meetings of the governing body and indeed served as Development Director, where he concentrated on the tertiary education sector for a time. At his home club, he served on the Committee and worked as a race organiser for many years. As Sandy said, “Bill was a do-er!”

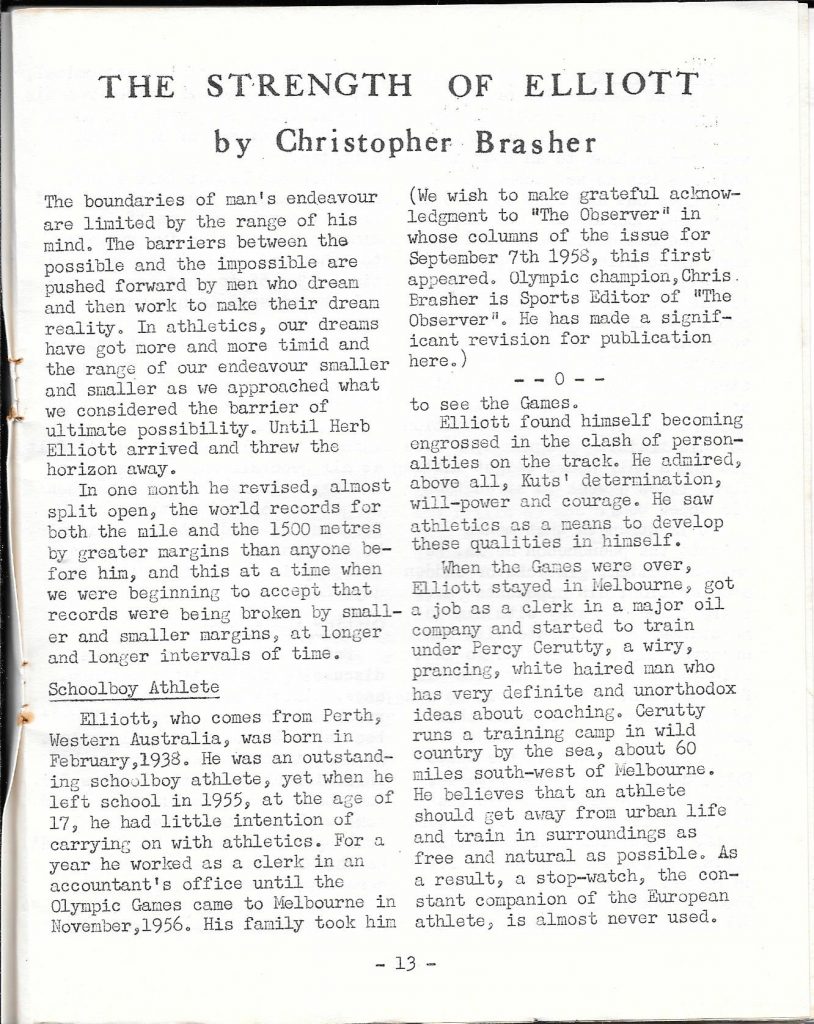

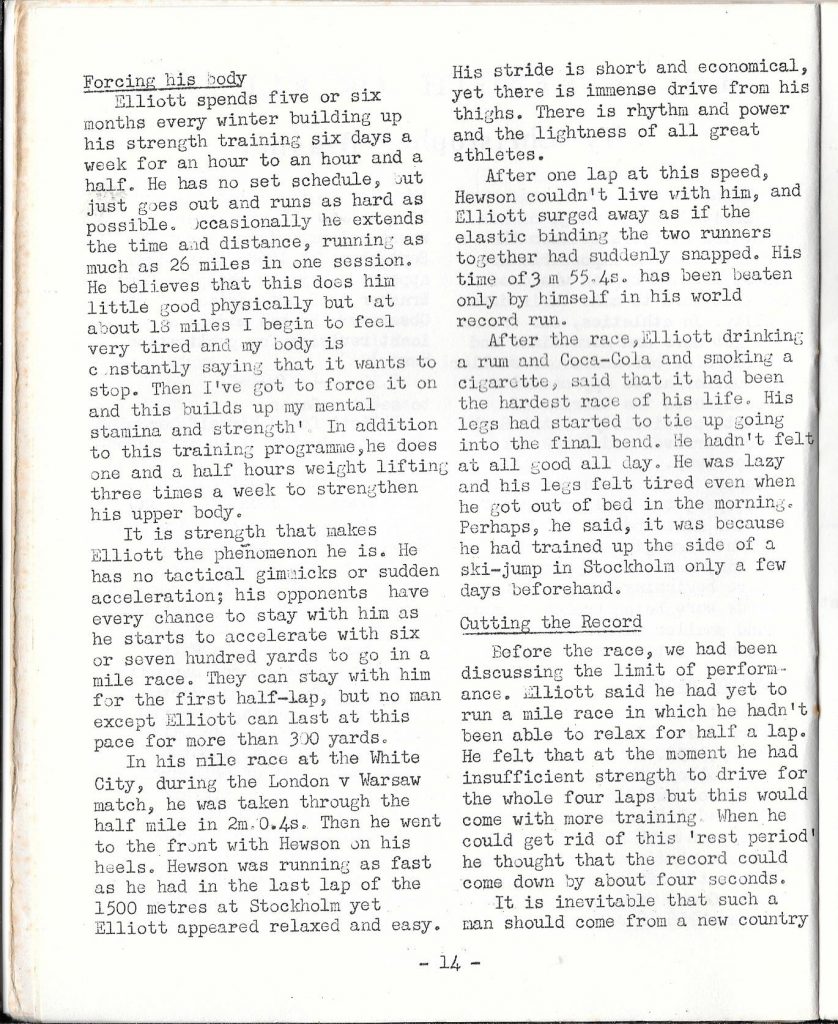

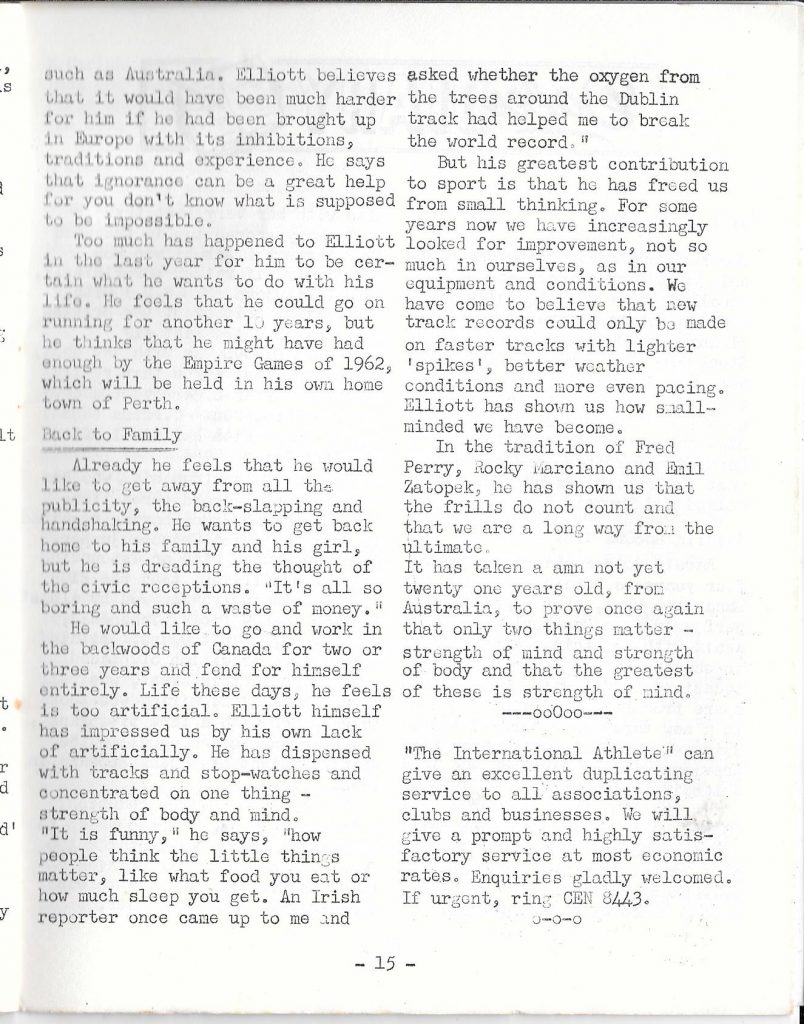

And of course, when speaking of Bill as a writer, we cannot forget his book which was published in April 2012/ A book launch at te Birnam Arts Centre after which they repaired to the Birnam Inn for eats. The publisher’s blurb reads:

YEAR of the PERFECT RUN http://peakpublish.com

sports journalist, and award winning writer, Bill Melville makes his own bid for sporting success.

At an age when most go pottering in the garden or taking the dog for a walk to “keep fit” the Birnam based Scot, a one time road runner before injury forced him off the tarmac, and for many years now an orienteer, travels across Britain and into continental Europe as he goes all out to score a perfect run.

Having given himself a year, to do it once or even make it a habit, his autobiography charts his travels, his successes and his failures.

He covers the problems facing the aging competitor. And working from a background in physiology, investigates the science of performance run-down.

It’s a “must read” for every sports person over forty.

At the same time the book looks at running sports and runners, the greats and not so greats, comments on the changes athletics and orienteering have seen, and on the world in general.

“I enjoyed writing it,” he says. “I hope it is a joy to read.”

Well, this reader enjoyed reading it. He discovered it hiding on a shelf in Waterstones in 2018 and read it in a night – and then went back shortly thereafter to have another look at particular sections. The book is more than a book about running or orienteering, it deals with all sorts of thigs like freedom of movement in Europe, sporting ethics and much more besides.

Samuel Johnson once said that you don’t need to be a carpenter to know when a table’s well made. While that’s true of most things, it is almost impossible to write about sport convincingly without having been a competitor yourself. The best Scottish sports writers of the last few generations have been in this category of having been in the arena – Doug Gillon, Sandy Sutherland and Bill have all been competitors. The level of competition is not really the point but the intensity is. Bill writes and talks in a language that these people understand. It informed his journalism and shines through in the book. A few quotes will demonstrate this.

From page four:

“Running on the track, roads or the country can make you feel good. Pub philosophers are likely to say that it is all the chemicals in the brain. The brain produces ‘endorphins’ which, like a number of manmade drugs, make you feel good. These are people who don’t run; people who feel pain and break sweat if they up the tempo to a fast walk down the boozer, let alone try to run there. ….. Running can hurt, especially at the end of a long outing when the muscles are both running out of energy and are suffering the combined effects of repeated contractions and are absorbing the impact.”

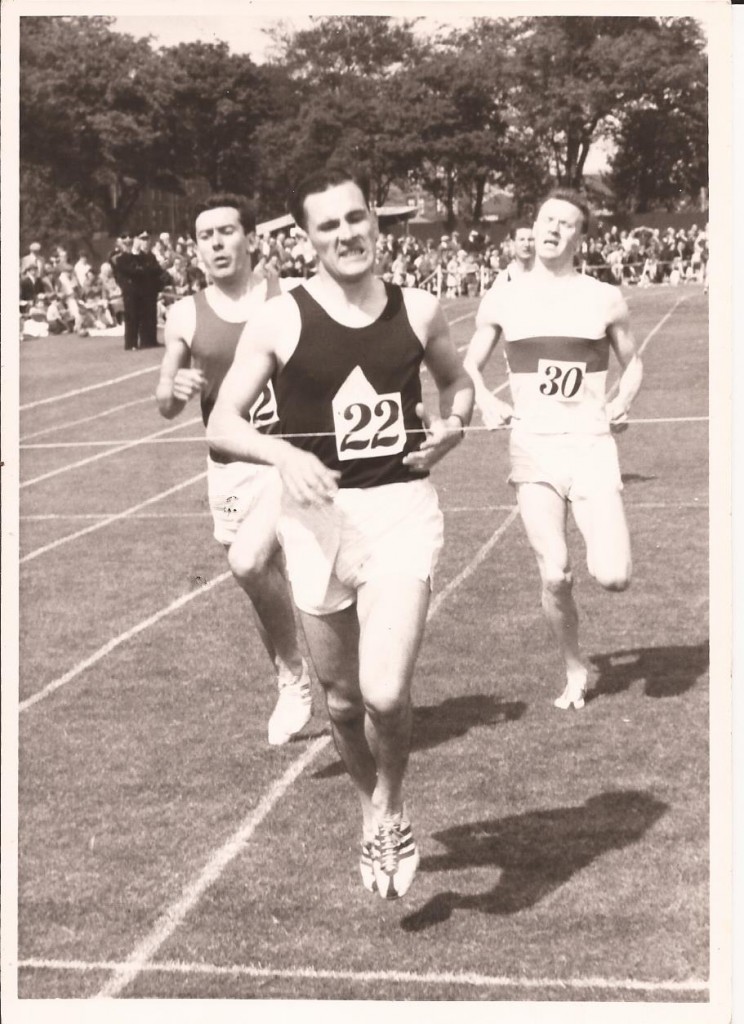

I doubt whether a non-runner could have thought that, never mind have written it. Or how about this one about the 800 metres:

“The fast staggered start, the jockeying for position at the break, a brief settling of the status quo round the bottom bend before heading for the bell, with half an eye watching out for any breaks or drives from behind. Then it is into the second lap with the field, sometimes strung out, sometimes bunched, everyone straddling a metaphorical line between perfection and going over the top, with anyone liable to make a telling move down the back straight or going into the final bend before making a final sprint for the line.”

You won’t convince me that that could have been written by a man who has not raced middle distance at some point in his life. There is no straining for the mot juste, no high flown language, just a man telling it how it is. Clear, unpretentious, direct, insightful. But if you need further convincing, how about this:

“finishing with my heart pounding and that unforgettable flavour of “blood” on my laboured breath, breath which grated like rusty files…”

I once coached a runner who often said after a good run “I could taste the blood“, it’s something that only distance runners understand. And there was often a bit like “I knew he was going to ‘tank’ me!”

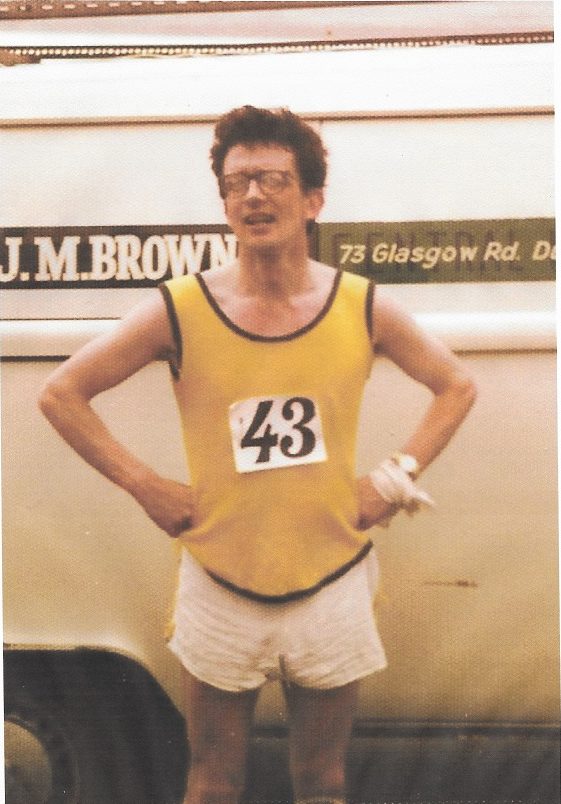

Bill being presented with the East of Scotland Trophy at Glenalmond

by East League Organiser Janet Clark

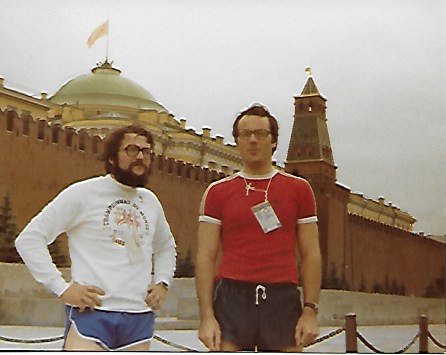

I have in the course of 60+ years in the sport read many a journalist and reporter on athletics. First of all there was George Dallas, a former international runner and outstanding athlete over distances from 100 yards to the half mile, who reported on athletics for the “Glasgow Herald” One of the three best journalists and reporters in my time in athletics. He knew what athletes wanted from the dailies: first a good results service, second a decent report on the race, third as much journalism as they good get – and in that order of importance. He had started writing in the 1920’s for the “Daily Record” under the moniker ‘Ggroe’ and after a wee hiatus for the War, took up the pen again, writing for “The Scots Athlete” and the Herald. He was an out and out reporter. He was followed at the “Glasgow Herald” by Ron Marshall who saw himself primarily as a journalist and he moved on to work on Scottish Television. Doug Gillon is the name that will resonate most with those who were runners in the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s and up to 2010. He wrote for the “Glasgow Herald” and covered many championships – read his profile by clicking on his name above. Doug had a good results service and was also a journalist of quality – he wouldn’t have lasted as long otherwise. Sandy Sutherland was based in the East of Scotland but wrote for a multitude of papers and also covered a wide range of sporting activity, mainly athletics and Basketball. I would put Bill up with George, Sandy and Doug as a reporter and with the latter two as a journalist. Bill was up there with the best who have dealt with athletics in the Press.

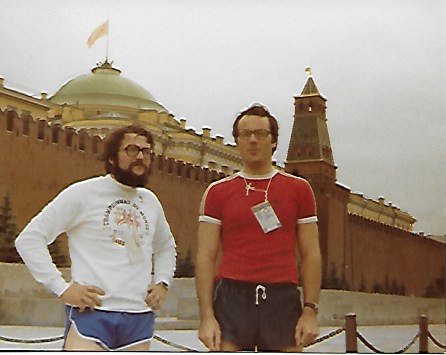

Doug Gillon and Sandy Sutherland in Moscow for the 1980 Olympics