MEMBERSHIP NOTES 22nd NOVEMBER 2017

MEMBERS

Welcome to the 30 new and 11 reinstated members who have joined or re-joined since 16th August 2017. As of 22nd Nov 2017, we have 545 paid up members, including 21 over 80 & 4 Life Members.

SUBSCRIPTIONS ARE NOW DUE FOR 2017/2018 Standard Membership £20 Non competing Membership £10 Over 80 Membership Free

NEWSLETTER The electronic version of the Newsletter is now the preferred option. Any member who would rather receive a printed Newsletter must contact David Fairweather, if they have not already done so. Please inform David if you add or change your email address.

Please send photos, news, letters, articles, etc for the next issue To: COLIN YOUNGSON TOMLOAN, SANQUHAR ROAD, FORRES, IV36 1DG e-mail: cjyoungson@btinternet.com Tel: 01309 672398

SVHC EVENTS Stewards/marshals are required for club races. The club appreciates all members & friends who volunteer to act as stewards/marshals. If you are not competing just turn up and introduce yourselves to the organisers.

STANDING ORDERS Thank you to the members who have set up standing orders for membership subscriptions. Please keep me informed if your membership details change (especially email addresses. Standing order details: Bank of Scotland, Barrhead, Sort Code: 80-05-54, Beneficiary: Scottish Veteran Harriers Club, Account No: 00778540, Reference: (SVHC Membership No. plus Surname). stewart2@ntlworld.com 0141 5780526 By cheque: please make cheque payable to SVHC and send to Ada Stewart, 30 Earlsburn Road, Lenzie, G66 5PF.

CLUB VESTS Vests can be purchased from Andy Law for £18, including Postage. (Tel: 01546 605336. or email lawchgair@aol.com)

NEW MEMBERS

NUMB CHRS SURN JOIN TOWN

2401 Kim Forbes 18-Aug-17 Kirknewton

2402 Tony MacDowall 18-Aug-17 Mitcham

2403 Donald Petrie 25-Aug-17 Houston

2404 Kay Conneff 28-Aug-17 East Kilbride

2405 Allie Chong 30-Aug-17 Newton Mearns

2406 Roger Homyer 31-Aug-17 Kingussie

2407 Martin Fitchie 06-Sep-17 Lenzie

2408 Thomas Wilson 06-Sep-17 Dundee

2409 Sara Green 08-Sep-17 Clovenfords

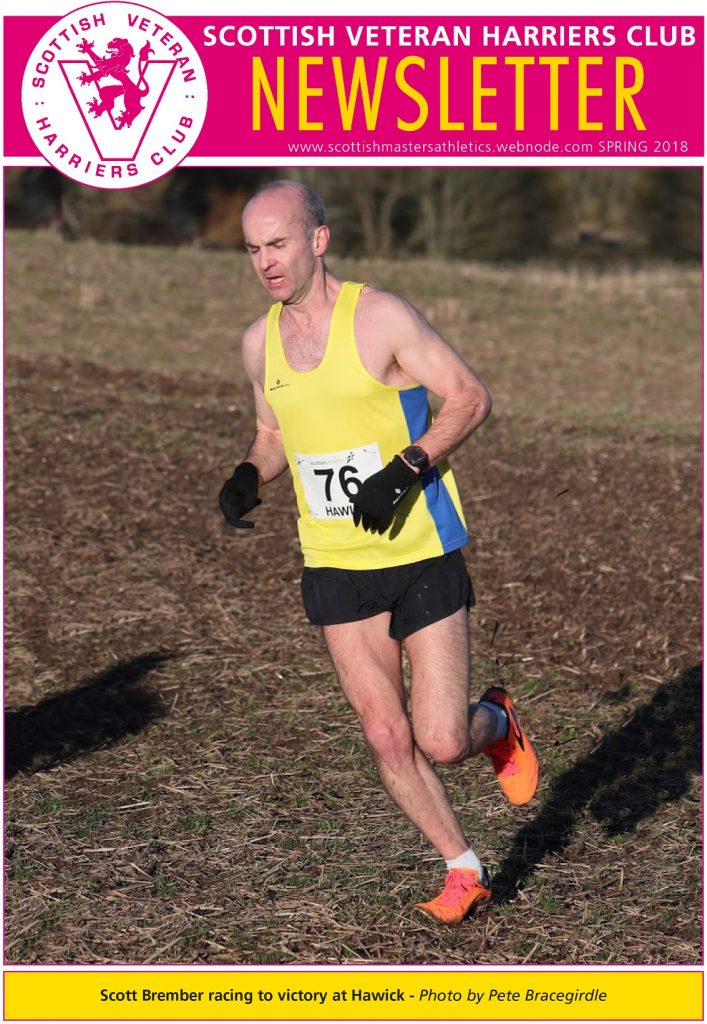

2410 Scott Brember 13-Sep-17 Stirling

2411 Alex Robertson 13-Sep-17 Penicuik

2412 Iain Whitaker 13-Sep-17 Edinburgh

2413 Francis Gribben 15-Sep-17 Norwich

2414 Karen Dobbie 16-Sep-17 Edinburgh

2415 Allan Cameron 16-Sep-17 Airdrie

2416 Mark Hand 16-Sep-17 Wishaw

2417 William Mitchell 16-Sep-17 Baillieston

2418 Michael Reid 20-Sep-17 Edinburgh

2419 John Oates 28-Sep-17 Glasgow

2420 Brian Thompson 09-Oct-17 Polbeth

2421 Alick Walkinshaw 06-Nov-17 Lanark

2422 Leon Johnson 16-Oct-17 Edinburgh

2423 Colin Welsh 20-Oct-17 Kelso

2424 David Wright 24-Oct-17 North Berwick

2425 Ross MacDonald 01-Nov-17 Tain

2426 Andew Corrigan 01-Nov-17 Edinburgh

2427 Louise Ross 09-Nov-17 Glasgow

2428 Gillian McGale 11-Nov-17 Glasgow

2429 Anthony McGale 11-Nov-17 Glasgow

2430 Gerard McConnell 15-Nov-17 Kirkintilloch

2152 Cris Walsh 08-Sep-17 Glasgow

2174 Fiona Dalgleish 14-Sep-17 Galashiels

1792 Stephen Allen 16-Sep-17 Wishaw

2131 Mark Johnston 16-Sep-17 Linlithgow

1855 Robert Quinn 16-Sep-17 Paisley

187 Brian Kirkwood 28-Sep-17 Bonnyrigg

2209 Andrew Harkins 03-Oct-17 Inverkip

700 Walter Ewing 15-Oct-17 Glasgow

747 Margaret Robertson 07-Nov-17 Broughty Ferry

2080 Anne Howie 10-Nov-17 Turriff

2246 Alastair Beaton 15-Nov-17 Inverness

Ada Stewart Membership Secretary

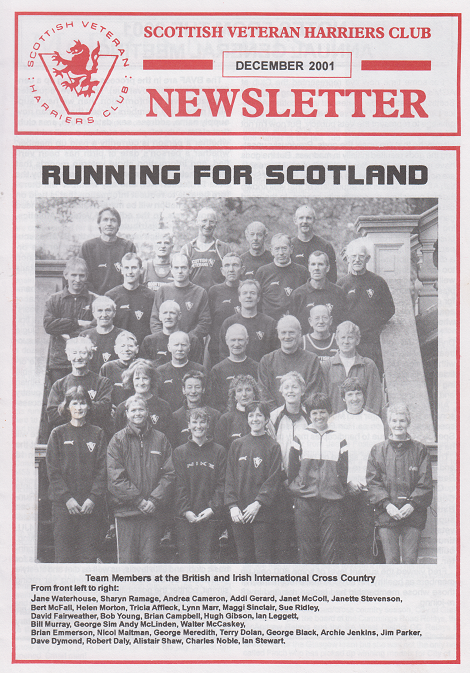

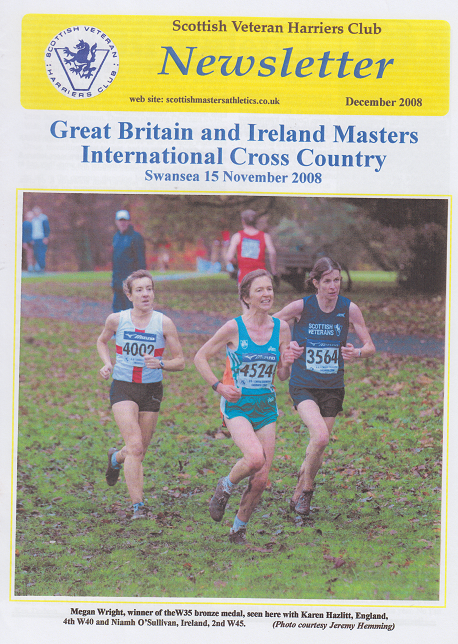

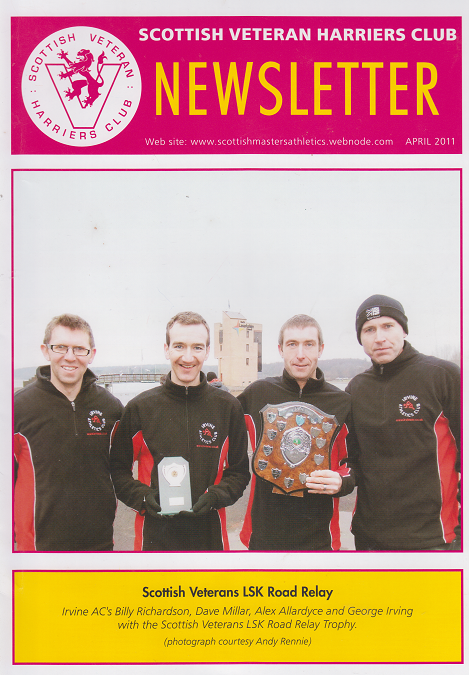

BRITISH AND IRISH MASTERS CROSS COUNTRY INTERNATIONAL DERRY, NORTHERN IRELAND, 18th NOVEMBER

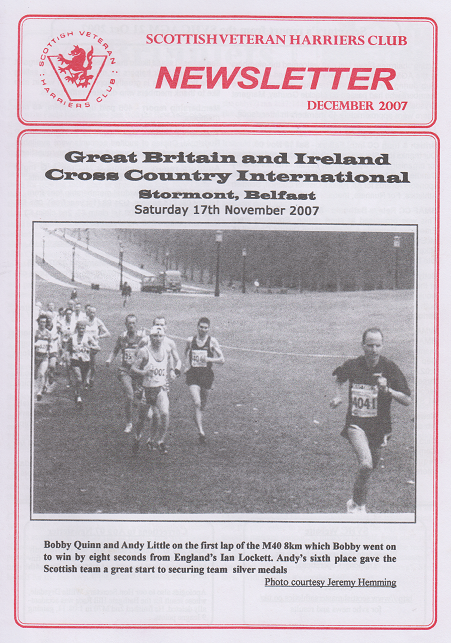

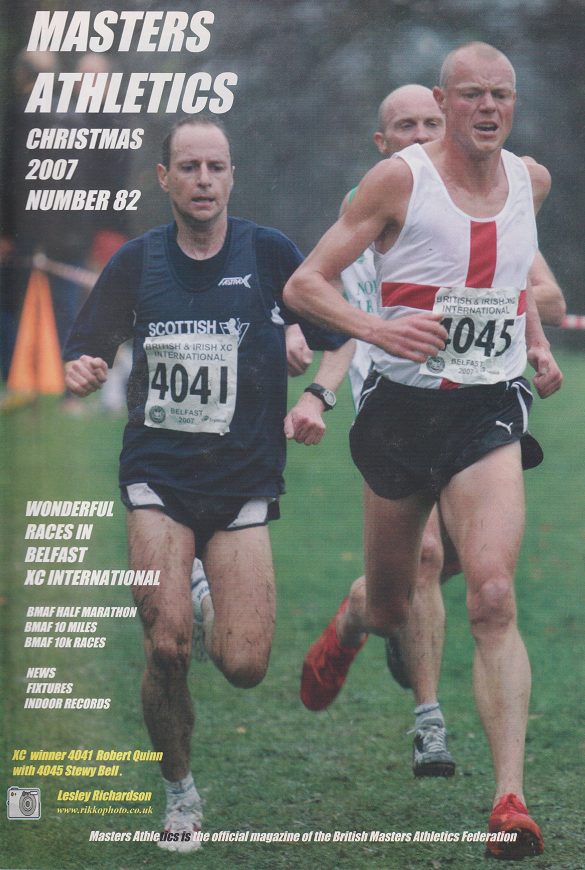

Robert Quinn near the finish line. Photo by Pete Bracegirdle

By means of planes and boats and trains (and buses and hire cars and taxis), Scottish Masters runners arrived eventually in Derry ready to compete in this fixture, which from our winter calendar is surely awarded the ‘Blue Riband’. The weather was cold but pleasant; and the course featured some deep mud, gentle undulations and plenty of mossy, damp grass, which produced strength-sapping racing conditions. Of course, when wearing a Scottish vest, you are meant to run as hard as possible, for your team, country, self-esteem and possibly bragging rights!

Our team managers – John Bell, Ada Stewart, Andy and Ishbel Law – were well-organised and always cheerfully motivating and supportive. The new kit looked splendid; and the hotel was an excellent choice. As usual the opposition, from England, Ireland, Northern Ireland and Wales, was formidable but many Scots ran well and we all tried our best on the day. Full results are on the Scottish Veteran Harriers Club website, but here is a summary.

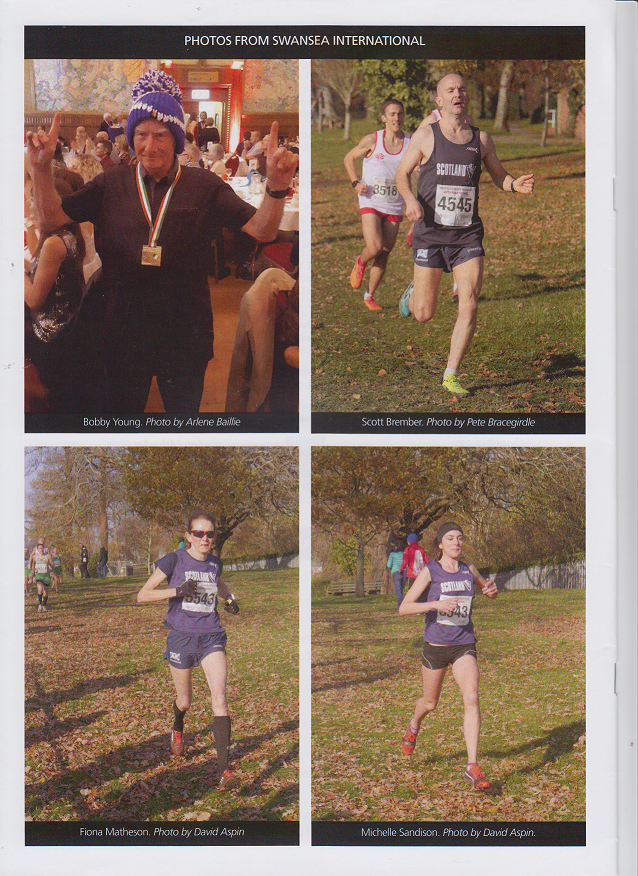

Race One was for all the female athletes plus the older guys. Katie White ran wonderfully well to win the W35 race, and was well supported by Michelle Sandison (4th) and Sara Green (11th). Our team finished second, only two points behind Ireland but in front of the Auld Enemy.

The W40s also shone, with Lesley Chisholm 6th (in the same time as Carol Parsons 7th) backed up by Ann Robin 12th. Team bronze medals were secured.

It was harder for the W45 team, which ended up fourth, led in by Jennifer Forbes (9th).

Sue Ridley, who has enjoyed such a long and distinguished running career, claimed that she was still suffering from an injury incurred three years ago. Poor lady, that would explain why she ‘only’ managed to finish 3rd M50, after outsprinting an Irish athlete for bronze! Her team was fourth.

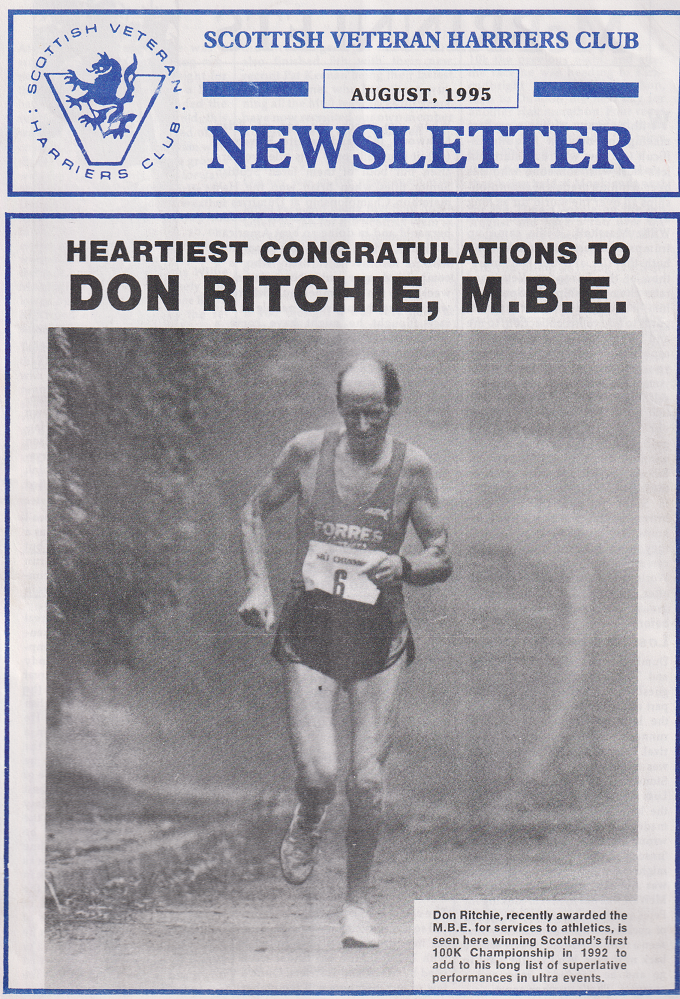

Now we come to Scotland’s bright star, Fiona Matheson, who currently graces the W55 category. Her victory was overwhelming – 79 seconds clear of the famous Irish runner Niamh O’Sullivan. Not only that: Fiona also outsprinted the legendary Nick Rose, who won the M65 contest. The Scottish team packed beautifully, with Pamela McCrossan, Yvonne Crilly and Anne Howie 8th, 9th and 10th. Another set of bronze medals was won, after an especially close team race.

Scotland was also third in the W60 competition, with Jane Kerridge and Innes Bracegirdle leading the team in 7th and 8th places.

Ann White (the mother of Katie, the W35 gold medallist) was equally successful when victorious in the W65 category, 32 seconds clear of England’s well-known Ros Tabor. With Linden Nicholson 7th and Jeanette Craig 8th, our team tied with England on 16 points – but their last counter was 9th so Scotland secured silver medals!

Liz Corbett ran very well for 3rd in the W70 race. Her team-mates, Margaret Robertson (8th) and Anne Docherty (9th) also raced strongly to ensure another set of bronze medals.

Perhaps our top male team was the M65 outfit, which finished second. However, the English proved impossible to beat, although their winning margin was only three points, due to an excellent silver medal for Tony Martin, and strong backing from Frank Hurley (4th) and Andy McLinden (6th).

The Scottish over-70s included three runners who were loudly worried, due to leg niggles or illness. Norman Baillie, making his first appearance in a Scottish vest, was the healthy, non-whingeing one, and fought to 5th place. Stewart McCrae (the victim of a heavy cold) still shot off as usual but eventually ran out of steam and was caught half a mile from home by more cautious team-mates, who had started slowly then moved through to 9th place (Colin Youngson) and 10th (Bobby ‘Forever’ Young). This ensured surprise team silver medals. Happily, Stewart recovered quickly and joined the others in a few select Derry pubs that afternoon. The incredible Bobby ran the first of these fixtures in 1988 and has now completed a record total of 26 ex 30. Colin told anyone prepared to listen that, in parkrun terms, he had now run for Scotland in every age group from M25 to M70.

In a close battle for bronze medals, our M75 team was squeezed into fourth place. Jim Scobie ran really well to finish 8th. That upbeat character, Ian Leggett (12th) is continuing the longest running career of any current SVHC member, having been a good senior athlete as long ago as 1963.

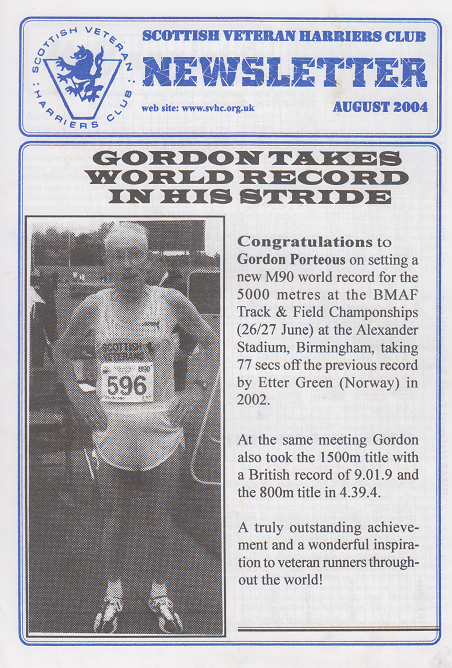

Race Two was for the M50, M55 and M60 categories. Robert Quinn (trade name: Bobby), who has achieved a tremendous amount and remains a top-class runner, only just missed out on an individual medal when he finished fourth M50. Michael McLoone (11th) and Ross McEachern (13th) backed up well but the team were unlucky to lose bronze on countback (by only two places).

Our M55s had a tough time but battled bravely nevertheless.

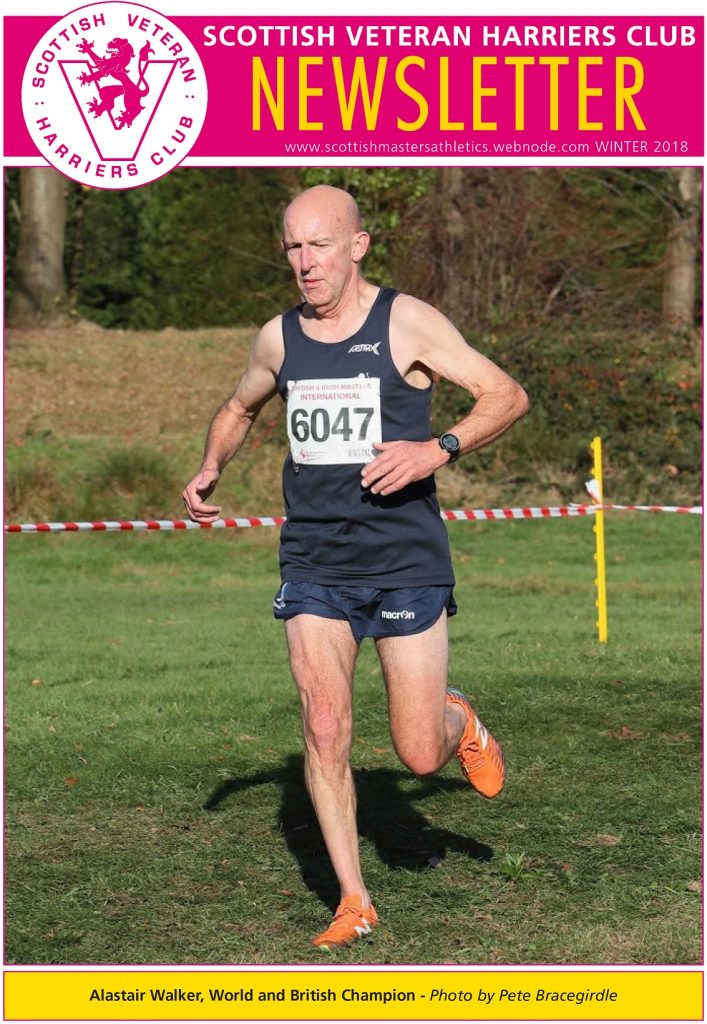

The M60 race produced one real surprise, Although there had been rumours that Teviotdale stalwart Alastair ‘Sammy’ Walker, in his youth a consistently successful runner, was very fit, no one was sure how fast, since he had never actually competed as a veteran! Here, in his very first Masters appearance, he came close to winning gold but was very happy to secure an impressive second place. His team-mates closed in admirably. Paul Thompson (6th) and Alex Chisholm (10th) finished second behind Ireland but in front of England.

Race Three featured M35, M40 and M40 age groups. Competition was especially fierce in the events for younger Masters athletes. The M35 men fought hard to fourth team position, with Jozsef Farkas first Scot in 12th place.

Iain Reid (first Scot in this race, just in front of Jozsef and Scott Brember) produced a very good performance for 6th M40, as did Leon Johnson in 9th; and the team won well-deserved. bronze medals.

Our best M45 runner was Scott Brember in a fine 6th place; and the team finished fourth.

The evening banquet was unforgettable, fortunately for good food, drink, social pleasure and well-organised medal presentations; and unfortunately for rambling speeches and an inexplicable lack of result sheets. Nearly all of us enjoyed this trip a great deal, however. The Derry folk were friendly and welcoming and most of the event was very successful, even if no one could actually locate the post-race showers. Roll on Swansea 2018!

MY FAVOURITE RACE: Campbell Joss

After some considerable thought, I have selected the Balloch to Clydebank road race as my choice. For someone of my vintage this refers to the old-style event which was run over a distance of 12.25 miles rather than the modern version, which is a standard half marathon.

Back in the 1970s, and even into the 1980s, point to point races on public roads were commonplace, and the route for this event was mainly on busy roads, finishing near to the Town Hall in Clydebank. The field was smaller than it is now but the runners had to weave their way through traffic and also encountered variable comments from people leaving the local alehouses on the route. The race usually started about 2.00pm on a Saturday afternoon and in these days the pubs closed at 2.30pm.

The standard at the front end of the race tended to be very high and many of the top Scottish distance runners of that era took part.

From my own modest perspective, I enjoyed some fierce competition with other club athletes who were regular rivals on the road and cross-country scene.

In later years, I was able to extrapolate a theoretical time from these efforts, which may have resulted in a half-decent time for 13.1 miles.

I believe there was more camaraderie at events like these, compared with the modern era – and it was usual for many of the competitors, including the elite runners, to retire to the local bar for a couple of beers.

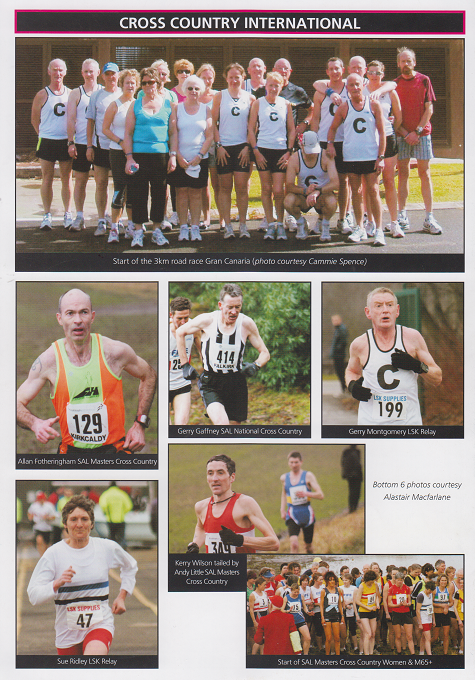

SUE RIDLEY INTERVIEWED

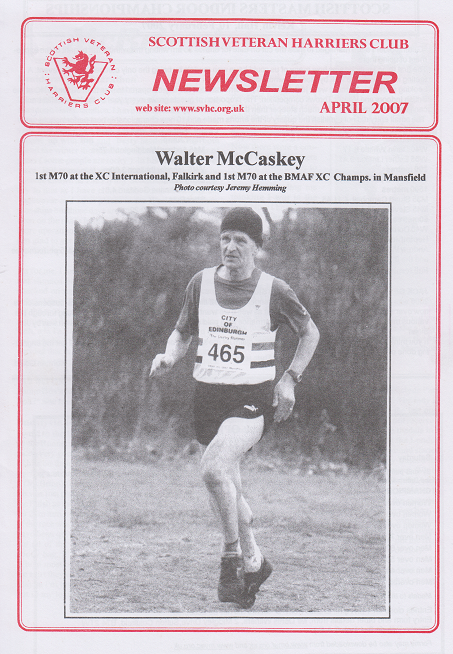

Sue at Derry

At Glasgow Airport while waiting for the flight to Derry, I took the opportunity to chat to my friend Sue when she was a captive audience in the café! She reminded me that, although in first year at secondary school she was involved in hockey, badminton and pony club events, she started running because there was a two-mile cross-country session on a wet afternoon. She finished first, although the second girl was trained by Johnny Robertson at Inverleithen. Sue joined his group and her long career started then.

She joined Edinburgh Southern Harriers as a sprinter (a skill which may have come in useful the day after we talked – see the Derry report). Then she took part in Scottish Women’s Cross Country Union Championships and particularly remembers a race in snow at Lanark – which she loved!

Sue must be the fittest chartered accountant around, quite defeating any stereotype of that profession. She is married with three children and, when she gets home from work, has to exercise several horses, so she has always been very busy. Consequently, she does not run many miles per week but makes the most of a shorter, more intense, training schedule. This has certainly paid handsomely, especially after 1990 when her coach became Bill Blair.

Ten months later, after a close battle with Sandra Branney, Sue won the UK Inter-Counties 10k Road Race title at Moreton-on-Marsh. She was Scottish Champion twice at 3000m and twice at 10,000m, as well as obtaining two 3000m indoor golds. Then in 1994 she became Scottish Senior National Cross Country Champion at Irvine Beach Park over a famous tough but fair course. Four Senior National team golds were taken between 1992 and 2013. This was during a five-year period when she was never out to the top three. Later that year she ran for Scotland on the track: 3000m in Israel; and 5000m in Istanbul, where although she ran fast, severely hot conditions depleted her immune systems so that she contracted an M.E. type disease which affected her for seven years and, very frustratingly, prevented her from achieving her full potential.

Nevertheless, Sue Ridley has continued to race very well: in Home International cross country matches as a senior and of course a Veteran/ Master. She has represented Scotland on the track, in the country, on the road, and also in the hills! She ran the European and World Mountain Running Trophy championships several times. Sue won the W35 European Masters 10k road title in Portugal and then finished second in the Half Marathon. She was also victorious in the 2009 W40 European Masters cross country championship in Ancona.

Naturally, umpteen Scottish Masters wins have been secured. The British and Irish Masters XC has been a special favourite, which Sue has run successfully on many occasions, including individual W35 gold at Croydon in 2004. She is undoubtedly a tough competitor but is invariably modest, cheerful and friendly.

Sue says that, on the track, her favourite event was 3000m. As a Masters athlete, cross country is enjoyed most. As a favourite race, the annual Lasswade cross country event (which used to be at Bonnyrigg but now takes place in Gorebridge) is nominated. Over many years, Sue has only missed a few of these events, which are run in November. The organisers, competitors and spectators are friendly folk. The course can be muddy, partly flat but otherwise undulating. Sometimes steep climbs and long descents feature. Nowadays, female athletes race 6 k along with under-17 boys.

An accident involving a horse three years ago may have slowed Sue Ridley’s racing speed but, as Derry proved, her success is likely to continue for many years yet!

RONHILL CAMBUSLANG HARRIERS

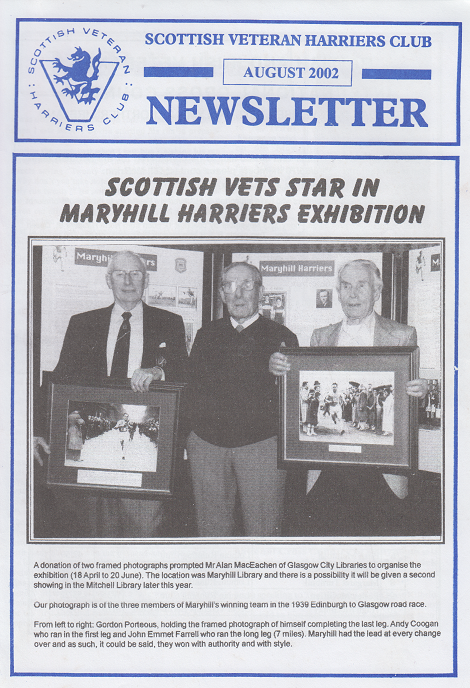

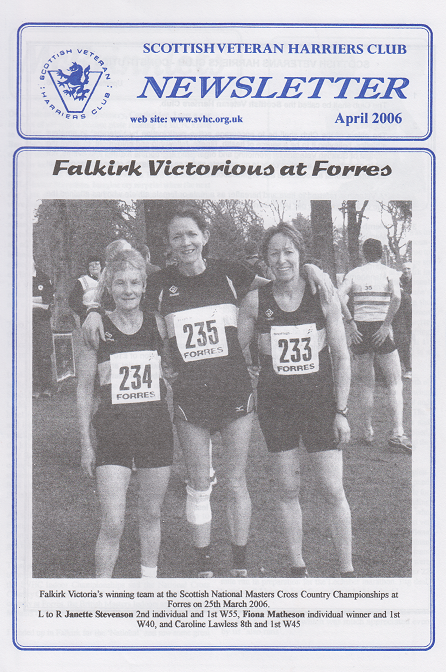

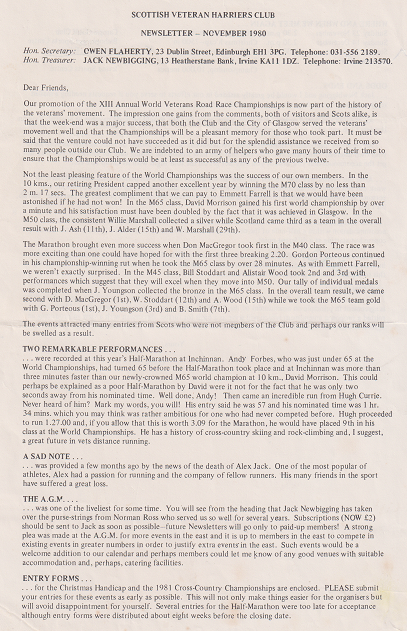

2010 BMAF Relay M50 gold team: left to right, Iain Campbell, Colin Feechan, Dave Thom, Frankie Barton, Frank Hurley, Archie Jenkins.

Cambuslang Harriers Masters teams have been Scotland’s finest for most of the last twenty years. Many genuine stars have worn the famous red vest and won thoroughly-deserved victories, medals and trophies. I can only marvel at the arduous training regime of top men like Kerry-Liam Wilson and Robert Gilroy – and at the clever effective preparation, involving fewer miles, by extraordinary Eddie Stewart.

However, I also remember being on the receiving end of the Cambuslang juggernaut! Although Aberdeen AAC veterans did well in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Metro Aberdeen RC became my club, we struggled to defeat our powerful rivals, particularly after that classy athlete Frankie Barton (Keith AC) joined Cambuslang second-claim. Metro did win the Scottish Masters XC relay twice, but a long frustrating series of silver medals ensued in the cross-country championships as well as relays. Oh well, it was a long time ago and it has been a pleasure to meet the Cambuslang guys in more recent years!

Below is an excellent article by David Cooney, who has been at the heart of his club’s amazing, sustained success. More photos and race reports will feature in the Spring Newsletter.

CAMBUSLANG HARRIERS MASTERS MEN’S TEAMS 1988 TO 2017

Although the first Scottish Veteran/Masters Cross Country Championship took place in 1972 Cambuslang Harriers did not feature in the M40 medals until taking team bronze in 1988 behind Aberdeen AAC (for whom Colin Youngson won individual gold) and Dumbarton AC. The Cambuslang quartet on that day was Eddie McIvor, Robert Anderson, David Fairweather and Andy Hughes. A second team bronze medal and 4 silver were gained over the next 7 years.

However, in 1996 Cambuslang lost its tag of being the bridesmaid and never the bride when winning the gold award thanks to Charlie McDougall, Archie Jenkins, Frank Hurley and Murray McDonald. The club went on to secure 7 successive team gold medals and from 2003 onwards the Lanarkshire club has only missed out on a team medal on one occasion. Indeed the total medal tally over a 30 year period from 1988 until 2017 reads as 17 gold, 7 silver and 3 bronze medals.

During these 3 decades Colin Donnelly and Kerry-Liam Wilson have won 9 medals, Archie Jenkins and Frank Hurley 5 and Frankie Barton and Stevie Wylie 4.

Further team success continued with the introduction of a M50 Team Championship in 2011 with Cambuslang having won the team trophy on 6 out of 7 possible occasions. The medal winning trio in 2011 was Frank Hurley, Frankie Barton and Gerry Reid. Eddie Stewart although he was first M50 and 5th overall in the race did not count for the M50 team as he was recorded as 2nd counter in the gold winning M40 team. However, Eddie has collected 4 M50 gold medals since then with 5 athletes on 2 namely Frank Hurley, Frankie Barton, Colin Feechan, Stan MacKenzie and Chris Upson.

Cambuslang Harriers M40 and 50 teams have enjoyed similar success in the Masters Cross Country Relays first introduced in 1996. Cambuslang finished 2nd in the inaugural event to a strong Metro Aberdeen team including Fraser Clyne and Keith Varney. However, in the following year the Cambuslang quartet of Frank Hurley, Jim Robertson, Jimmy Quinn and Archie Jenkins were victorious over Clydesdale with the B team of David Fairweather, Murray McDonald, Freddy Connor and Peter Ogden taking bronze position.

In the 23 year history of the event Cambuslang has collected 13 gold, 3 silver and 2 bronze medals including 6 consecutive victories between 2011 and 2016.

Also in the 6 year lifetime of the M50 relay 4 gold medals and 1 silver have been won by the club. Dave Thom, Colin Feechan and Iain Campbell were the team members in the inaugural race. The most frequent medal winners in this category have been Colin Feechan with 3 and Dave Thom and Colin Donnelly both on two.

Cambuslang Masters teams have also been very prominent on the Scottish road running scene firstly in the Scottish Veteran Harriers Alloa to Bishopbriggs 8-man relay followed by the 6 man Torrance Relay and then the Scottish Athletics Masters M40 6 man relay introduced in 2005 and the M50 4 man event from 2013. Cambuslang won team gold on the point to point course in 1988 and 89, team silver in 1990 and bronze in 1991 and 92.

When the race was moved in 1993 to the hilly roads around Torrance (although termed a flat course by race organiser Danny Wilmoth) for safety reasons, Cambuslang continued to excel winning silver in that year followed by 8 successive gold medals up to 20002. No race was held in 2001 due to an outbreak of foot and mouth disease. During that period Charlie McDougall, Archie Jenkins, Frankie Barton, Frank Hurley, Jim Robertson and Ian Williamson proved to be the mainstay of the club’s success.

From 2005 when the event came under the auspices of Scottish Athletics Cambuslang has lifted 11 gold, 1 silver and 2 bronze medals with Kerry-Liam Wilson featuring on 7 occasions and Dave Thom and Jamie Reid on 4.

The M50 squad has been unbeaten in its 5 year history and Colin Feechan has been ever present with Dave Thom on 3 medals and Stan MacKenzie and Chris Upson on 2.

Masters teams from Cambuslang Harriers have also made their presence felt in UK events on country and particularly road. Between 1999 and 2004 in the original O40 8-man road relay event Cambuslang won 3 gold, 2 silver and 1 bronze with the O50 quartet taking 2 bronze medals in 2002 and 03. The club first experienced the special atmosphere of this event at Sutton Coldfield Birmingham in 1989 when finishing just outside the top 20. The evening before the race Cambuslang and Morpeth runners mingled in the bar listening to the exploits of Morpeth’s Jim Alder, one of the all-time greats of Scottish distance running. Two very respectable 5th places in the mid to late 90s demonstrated the progress made by Cambuslang. However, 1999 was the breakthrough year when the team of Barnie Gough, Dave Dymond, Freddy Connor, Frankie Barton, Charlie McDougall, Eddie Stewart, Frank Hurley and Archie Jenkins upset the apple cart to gain a surprise victory from their more fancied English rivals. This win was very special to the club as it was its first UK team championship medal and it did not go down well with a certain English journalist who considered the Cambuslang runners to be “Scottish raiders” in what was a UK event!

The second victory in 2003 was perhaps just as special as the club set a course record with all 8 runners being inside 16 minutes for the tough 3 mile circuit. No other club had previously managed this but Ian Williamson, Dave Dymond, Dave Thom, Colin Donnelly, Ross Arbuckle, Frankie Barton, Alex Robertson and Jack Brown managed to do so with Alex setting a club record of 14.55. However, his record was short lived as the following year John Cowan recorded the fastest race time and a new club record of 14.51 while Jack Brown equalled the old club record. Both were on the last 2 legs and ensured another team gold. Robert Gilroy later in 2015 reduced the club record to an impressive 14.47.

During that period Frankie Barton and Dave Dymond were ever present with Colin Donnelly making 4 appearances and Archie Jenkins, Frank Hurley, Freddy Connor, Ian Williamson and Dave Thom featuring in 3 of the races.

The M50 sextets added to the club’s celebrations in 2002 and 2003 by securing 2 bronze medals. Archie Jenkins, Freddy Connor, Barnie Gough and Tom McPake appeared in both races.

Although a M35-39 age group was introduced in 2008 Cambuslang did not field a team in this new age group until 2010 when the quartet of Greg Hastie, Charlie Thomson, Kerry-Liam Wilson and Jamie Reid was victorious.

The following year the M35-39 group was incorporated in to a M35-44 with 8 to count and Cambuslang again took gold thanks to Alan Ramage, Johnny MacNamara, Mick O’Hagan, Robert Gilroy, Greg Hastie, Kerry-Liam Wilson, Iain Campbell and Jamie Reid. Silver medals then followed in 2012, 15 and 16. Jamie Reid appeared in 5 of the teams with Kerry-Liam Wilson and Robert Gilroy in 4 and Greg Hastie and Charlie Thomson in 3.

Also in 2010 the M50 team of Colin Feechan, Frankie Barton, Archie Jenkins, Dave Thom, Iain Campbell and Frank Hurley added to the earlier gold medal won by their younger 35-39 team mates. That double victory with the added bonus of fielding a M60 team for the first time of David Fairweather, David Cooney and Robert Anderson was another special day for the club.

There has also been gold and silver success for the M55 team in 2015 and 17 with Colin Feechan and Paul Thompson present in both races.

Elsewhere on the road at UK level the M35, M40 and M50 age groups have won team gold over 5K, 10K and ½ Marathon with silver in the 10 mile event. The M40 team achieved 5K gold in 1999 at Annan thanks to Dave Dymond, Freddy Connor and Barnie Gough. There was further golden success at Horwich in 2003 and 05 with individual silver medallist Jack Brown spearheading the 2003 team and individual bronze medallist Charlie Thomson leading home the 2005 squad. The M50 trio of Charlie McDougall, Terry Dolan and David Cooney lifted bronze in 1999 and there was a further M50 bronze in 2005 by courtesy of Archie Jenkins, Frank Hurley and Barnie Gough. More recently in 2013 Dave Thom, Ian Williamson and Colin Feechan added team silver in the over 45 category.

At 10K the M50 trio of Freddy Connor, Barnie Gough and Ian Gordon secured gold at Bishop Auckland in 2002 which was followed by a silver medal at Motherwell in 2005. Not surprisingly the M40s took gold at Motherwell with Jack Brown first, Charlie Thomson second and Frankie Barton 5th. Again in 2013 on home soil at Pollock Park Cambuslang recorded a golden 10K double thanks to a one, two from Ben Hukins and Kerry-Liam Wilson with Robert Gilroy in support for the M35 team and the closely packed over 45 trio of Dave Thom, Colin Feechan and Ian Williamson.

Earlier in 1998 at Preston M40 10 mile silver medals were won by Frankie Barton, Eddie Stewart and Charlie McDougall.

Finally at the half marathon distance at Kirkintilloch in 2016 first and second placed Robert Gilroy and Kerry-Liam Wilson with back up from Stan MacKenzie were crowned the UK M40 masters champions.

While not attending UK cross country events as regularly as road races due to fixture clashes and the long distances involved the club nevertheless also has an excellent record in that discipline. Cambuslang took advantage of the BMAF Cross Country Championships being held at Irvine in 2003 with Colin Donnelly leading Jack Brown, Dave Dymond and Jimmy Zaple to M40 team gold. The club successfully defended the M40 title the following year at Durham thanks to Alex Robertson, Colin Donnelly, Ross Arbuckle and Dave Dymond. Cambuslang did not contest another Championship until 2014 when the event was staged at Tollcross in Glasgow. Double gold medals were achieved by the M35 and M55 teams with Robert Gilroy, Kerry-Liam Wilson and Jamie Reid representing the younger age group and Colin Feechan, Frankie Barton and Frank Hurley counting for the older group.

The Cambuslang M40 team of Gerry Reid, Dave Dymond, Ronnie Bruce, Colin Donnelly, Frankie Barton and Ross Arbuckle made its debut in a BMAF Cross Country Relay at Darlington in 2001 and scored an emphatic victory after taking the lead on the second leg. The club travelled further south to Croydon the following year with two age group teams. The M40 sextet of David Marshall, Gerry Reid, Colin Donnelly, Ian Williamson, Frankie Barton and Dave Dymond and the M50 quartet of Terry Dolan, Freddy Connor, Archie Jenkins and Barnie Gough picked up silver just losing out on gold on the last leg in their respective races. The Scottish Veteran Harriers hosted the event at Bathgate in 2007 and Cambuslang swept the board in the M35, M40 and M50 events. The M35 representatives were Kerry-Liam Wilson, Greg Hastie, David Rodgers and Stevie Wylie while the M40 runners were Ross Arbuckle, Dave Thom, Benny McLaughlin, Robert Lyon, Gerry Reid and Colin Feechan with Freddy Connor, Archie Jenkins, Frank Hurley and Frankie Barton making up the M50 quartet.

The club was not involved in any further relay competitions until 2016 when Frank Hurley, Dave Thom, Paul Thompson and Colin Donnelly won the M55 title at Long Eaton. Unfortunately the date for the BMAF Relay was switched this year to clash with the Scottish Cross Country Senior and Masters Relays and presented the club with a difficult decision to make. It was agreed to contest both events although this was splitting the club’s forces. The M55 team consisting of Colin Feechan, Dave Thom, Alick Walkinshaw and Colin Donnelly was given the opportunity to defend its title and was accompanied by a M65 squad of Peter Ogden, Barnie Gough and Frank Hurley. Both teams were among the medals with the younger quartet taking silver and the older trio bronze.

Nowadays English officials and runners are accustomed to seeing Cambuslang compete in UK events held out with Scotland and they appreciate the club’s appearance given the long journeys involved.

If pressed on what I consider to be Cambuslang’s Harriers Masters greatest achievement(s) I would chose 3 performances at the BMAF Road Relays held at Sutton Coldfield, the spiritual home of UK road relay running. The first UK victory for the M40 team in 1999 was obviously special as was regaining the title and beating the course record in 2003. However, achieving a double victory for the M35 and M50 teams in 2010 also merits inclusion.

The question of how Cambuslang Harriers Masters Men Section (and indeed the club itself across all the male age groups) has remained so successful for a 30 year period needs to be considered. A variety of factors come into play to explain why a relatively small club with a total membership of no more than 130 athletes has enjoyed such lasting success. Having a number of talented athletes supported by a good core of club runners all sharing a sense of ambition and imbued with a strong club spirit and mindful of club tradition is a very important ingredient. The availability of excellent structured coaching with Mike Johnston at the helm and the positive support and encouragement from committee and club members current and past such as Robert Anderson, Colin Feechan, Dave Thom, Barnie Gough, David Cooney, Owen Reid, Des Yuill, Jim Scarbrough, Cameron Brown, Jim Orr and Ian Gordon are vital too.

The maxim of success breeds success holds true for Cambuslang Harriers. The early masters’ teams from the late 1980s onwards took inspiration and belief from their younger club mates when the under 17 and under 20 teams from the early/mid 1980s and senior teams from 1988 regularly began to strike national gold. Indeed 4 of the senior athletes from the gold winning team of 1988 were later to carry forward their exploits to masters’ level – Colin Donnelly, Eddie Stewart, Ross Arbuckle and Charlie Thomson.

Undoubtedly the club’s growing success at masters’ level and its known ambition to compete at UK level attracted other runners to Cambuslang. Dave Dymond who had lived in Exeter and ran for them in the BMAF Road Relay when Cambuslang had also competed asked to join the club for that very reason when he moved shortly afterwards to Largs. Ian Williamson resident in Shetland but never, once he became a veteran, having a team to support him when on the mainland, was keen to sample team competition and to join a club which would further his running ambition.

Another consideration is the famous or infamous Tuesday night club 8 mile tempo Hampden run where no prisoners were taken. This was instrumental in raising the fitness and fostering the team spirit of the Cambuslang runners. If Alex Gilmour took his teeth out before the run then everyone knew that the pace would be extra hot. While not quite on the same scale as previously, evergreen masters such as Frank Hurley, Dave Thom, Colin Feechan and Paul Thompson along with new M40 and club captain Iain Reid and a group of U20, senior men and women can be found on that Hampden circuit today.

Finally loyalty from athletes to the club cannot be overlooked. Although Eddie Stewart left Scotland in 1993 for Prague where he still lives, he has continued to represent the club whenever he can and has the almost unique record of winning Scottish Masters XC Titles at M40/45/50/55/60. (Greenock’s Bill Stoddart, frequently a World Veteran champion, previously achieved this feat.)

It is possible that Colin Donnelly who also moved from Glasgow to North Wales for a lengthy period but continued to represent Cambuslang may shortly emulate Eddie’s record if he can stay injury free. Colin has so far achieved gold in the M40/45/50/55 age groups.

While every athlete mentioned in the article has played a crucial part in creating and/or sustaining Cambuslang’s incredible team success a number of names have appeared more frequently and/or over a lengthy period of time. The reader will be able to identify them.

While this article has mainly focused on team success it is worth remembering the Cambuslang athletes who have achieved individually at European and or World Level namely Willie Marshall, Kerry-Liam Wilson, Paul Thompson, Colin Donnelly, Archie Jenkins, Jack Brown and Ian Williamson. On a final note the Cambuslang’s Ladies’ Masters’ squad of Jennifer Reid, Bernie O’Neil, Erica Christie and Claire Mennie, who won senior team gold last season in the Scottish 10 Mile Road Championship and bronze in the Scottish Masters Road Relay, also deserve recognition.

By David Cooney

LONDON OLYMPIC MARATHON, 1908 continued – by Roger Robinson

Jack Andrew promptly declared Dorando Pietri the winner, presumably announcing it through that giant megaphone. As a long-time stadium announcer, I’m very grateful I wasn’t working that day. The American team immediately lodged a protest, which of course was upheld. They had already lodged four in four days of the Games, which shows something of the tension between the hosts and their most successful guests.

It started when the American flag was only at half-mast during the opening ceremony. (Well, it really started in 1776. British Imperialism was at its height in 1908, and America represented its one great failure.) In the 400 meters, the race was declared void, one American was disqualified, all four withdrew, and a single Brit (1906 Scottish Champion Wyndham Halswelle, who had broken the Olympic record in the heats) did the re-run final solo.

The American Bishop of Pennsylvania, invited to deliver the Sunday sermon at St Paul’s Cathedral in London in the middle of the Games, tried to defuse the dispute by coining the phrase “the important thing in the Olympic Games is not so much winning as taking part.” Baron Pierre de Coubertin at the post-Games Government banquet, only a few hours after the Hayes/ Pietri drama, quoted that phrase, and it has become enshrined in the Olympic creed.

What Hayes and Pietri thought about it is not recorded. Anyway, Johnny Hayes was the winner. How well was Hayes running during those climactic final seconds? All eyes were (and still are) on Pietri at the tape, but an important question is whether Hayes was charging him down or struggling along in a similar state of near-collapse.

One American spectator said that Hayes “trotted into the stadium as fresh as a daisy,” and Doyle said he was “well within his strength,” but other accounts say things like he “struggled in second, apparently befuddled by strychnine” (Rob Hadgraft, The Little Wonder, p. 220). Jack Andrew also reported that he “assisted Hayes in the same way” as he did Pietri. Why did he need assistance? What shape was he in?

An Italian observer’s sketch reproduced by Martin and Gynn (1979) shows the points where Pietri collapsed, and marks with an X Hayes’s position on the last bend as Pietri reached the tape. Assuming it is accurate (and it fits with Doyle’s and Cook’s accounts), this puts Hayes about 150 yards behind as Pietri reaches the tape (since the full distance on the track was 385 yards). Their finishing times were 2:54:46.4 and 2:55:18.4, a 32 second gap. 150 yards in 32 seconds is 93 second 440 speed, or 6:12 mile pace. (I’m no mathematician so please check). That’s hauling, at the end of a 2:55 marathon, average pace 6:41. So Hayes finished fast, by any standards.

To imagine him at 6-minute mile speed charging in pursuit of the tottering crumpling Pietri is to understand the full frantic drama of that scene. No wonder the crowd was in frenzy. No wonder the officials around Pietri were in a state of near panic. Andrew’s motives in giving Hayes the same “assistance” may not have been as pure as I’d like to think. You don’t need assisting if you can run 6’s. If Hayes “collapsed” or fell down after the line, well, so do plenty of us, and it doesn’t mean we were not running strong. For astute tactics executed with judgment and determination, few Olympic marathon winners have been more deserving than Johnny Hayes.

Next day, after the awards ceremony, he was carried off the track on a table held by six American teammates, with “the Greek trophy” awarded for the Marathon, a statue apparently representing the dying Pheidippides.

Pietri had been carried off on a stretcher. But he did not die. He was taken to a hospital where he recovered quite quickly. The New York Times says he “was almost too weak to answer questions when seen tonight [after the race]”, but the next day he looks quite perky in the picture where he is receiving his big gold cup from Queen Alexandra. The New York Times said he “walked briskly around the track and up the steps,” which is more than I could ever do the day after a marathon. He received “a perfect ovation, the people rising in their seats and cheering him for fifteen minutes.” The American part of the crowd “kept up the demonstration long after the others had quieted down.” (New York Times)

The Brits also took the little Italian to their hearts. He became a symbol of gallantry, and of noble breeding. Conan Doyle pronounced portentously, “No Roman of the prime ever bore himself better than Dorando… The great breed is not yet extinct.” If it seems a bit of a stretch to dress up the sweaty little small-town cake maker in a toga as one of the noblest Romans of them all, well, the Brits in 1908 believed in “great breeds,” especially their own, and saw themselves as inheritors of Rome’s imperial destiny. It’s also possible that some of this spin campaign to apotheosize Pietri as the true winner of the marathon might have been meant to take the smile off the Americans’ faces.

No question that Pietri was amazingly gutsy. To get to your feet once after collapsing with heat exhaustion near the end of a marathon is tough. To do it six times is astonishing. Pietri earned his iconic place as a symbol of courage and endurance. But for my money, as a runner, it takes just as much courage to let the entire field in a major race run away from you at the start, sit sedately back while Brit spectators jeer from up every tree, allow the leaders to go away by nearly ten minutes, and wait till after 15 miles before you begin to make any ground on them. That’s really gutsy. The marathon is a sporting event that tests judgment, as well as stamina and courage. By that full test, Johnny Hayes was emphatically the winner.

Pietri misjudged by probably only two or three minutes. That extra 1 mile, 385 yards indeed sank him. (Even the program said the distance was 26 miles. The official race rules said 40 kilometers.) But Hayes got it dead right, and all credit to him.

The other thing that Pietri came to symbolize is the public’s mixture of horror and fascination with physical exhaustion. This was the appeal of fights to the death in the Rome Coliseum. A hundred years before the Pietri race, in the early 19th century, the big sport was bare-knuckle boxing, which went on till one contestant was smashed to pulp. Some of the greatest fights lasted over 60 rounds.

In the later 1800s, after boxing was regulated, there were still plenty of sporting events where crowds paid well to watch competitors run or walk to exhaustion, as in the six-day “Go as you please” races that have been described in Marathon & Beyond.

Pietri went beyond exhaustion in front of the biggest crowd in history, and for the highest stakes. Knowledge of the causes for exhausted collapse was primitive, and included a good measure of sheer superstition. One doctor who examined Pietri at the hospital pronounced, “His heart was displaced by half an inch.” I have never worked out how he knew exactly where it had been to begin with. It was Pietri’s “supreme will within” that most impressed Conan Doyle. He caught perfectly, in a phrase that deserves to be better known, the appeal of this kind of extreme effort: “It is horrible, and yet fascinating, this struggle between a set purpose and an utterly exhausted frame.” Some find it so horrible that they disapprove. The London Daily News struck a pose of shocked protest. “Nothing more painful or deplorable was ever seen at a public spectacle…It may be questioned whether so great a trial of human endurance should be sanctioned.”

Yet we all love to watch people risk death, even as we fear it, and even though we’re sometimes ashamed of liking it. My brother is a commentator at TT motorcycle racing, and lives every week with a public that is half morbid in its fascination with his sport. I don’t watch Nascar racing but suspect that sometimes there are crashes.

It was this element of near-death danger in the Pietri drama that gave the new sport of the marathon its place in the shared human imagination. However purist we are about marathon running, and however positive in our beliefs about it, we have to acknowledge that element in its popular appeal.

Having just published a book about the marathon, I know that I could not decline to include the stories of Pheidippides, Pietri and Jim Peters. They are intrinsic to marathon culture.

But Pietri’s sufferings were not the whole story. Look at any photo of the 1908 Olympic marathon, and you’ll be struck by the hordes of spectators. One wonderful picture shows dozens of them who have clambered up trees in Windsor Great Park to get a view of the start. People are lined two deep on Windsor’s Castle Hill in the pictures of the athletes walking up towards the start, and then racing downhill on the first half mile. Several photos in the official report show a crowd at Willesden, about 23 miles, as good as those in modern Brooklyn. “The people who lined the course treated us finely, and they were of great assistance in cheering us up and giving a man heart,” Joseph Forshaw told the New York Times. One estimate I have seen put the crowds at 250,000. I’ve no idea how they calculate these figures, but the crowds were evidently bigger than at Athens in 1896, so it seems safe to say the 1908 Olympic marathon was, in terms of public response, the biggest sports event in history.

Why? It was just 56 under-trained, little-known guys doing something repetitive and not specially interesting that we now know can be done very much better. Yet there was huge public interest. Probably the main reasons are the same that bring out the crowds at modern Boston, London, or New York. (1) A race is a race, the purest and best of all sports contests. (2) The marathon has a sense of historical significance that no other event equals. (3) There is the “horrible fascination” of watching apparently ordinary people heroically push themselves to the extreme that marathon runners do, (4) It’s international so gives the buzz of patriotism, and (5) The marathon happens right outside your front door, yet brings contestants from all over to do battle on your street.

With that 1908 race immediately becoming almost mythic, the marathon entered popular culture, and the English language (and other languages, of course). After the inspiring Greek victory of Spiridon Louis in 1896, the phrase “marathon race” (soon just “marathon”) denoted the new sporting event, with added associations of long and heroic effort. After Pietri, it took on the extra meanings of a struggle against exhaustion, or gallantly surviving long-term difficulty. The word was applied outside running for the first time only four months after Pietri’s race, when the London Daily Chronicle reported a potato-peeling contest named “The Murphy Marathon” (Nov 5, 1908). It entered literature the next year, when H.G. Wells was writing his novel The History of Mr. Polly (published 1910). A criminal called Uncle Jim warns Mr. Polly off his patch, appearing one evening while Polly is taking his walk. Wells spares the reader Jim’s more colourful adjectives. Mr. Polly…quickened his pace. “Arf a mo’,” said Uncle Jim, taking his arm. “We ain’t doing a (sanguinary) Marathon. It ain’t a (decorated) cinder track. I want a word with you, mister. See?” If the low-life Uncle Jim, or the non-sporting H.G. Wells, knew about the marathon, it had arrived. (Wells was a keen bicyclist but had no interest in organized sports.)

Such public interest produced a great era of marathons. The rivalry between Pietri and Hayes was too colourful to let go. They were quickly signed by an enterprising New York promoter for a head-to-head race in November 1908. Pietri gave up his amateur status and endorsed Bovril (a beef tea drink) as the cause of his rapid recovery. (Another shaft for the race organizers, who had sponsorship from the rival Oxo, which was “appointed Official Caterers” to the competitors.) Tom Longboat, the Boston record-breaker with the exotic appeal of being a Canadian Onondagan Indian, also declared himself available for prize-money racing. So did England’s Fred Appleby, another star who had suffered a bad day at London. So did an exciting new name to the marathon, multiple world record-holder Alf Shrubb of England, the world’s greatest track and cross-country runner. The official report on the 1908 Olympics grumpily dismissed all this as an “epidemic of ‘Marathon Races’ which attacked the civilized world from Madison Square Garden to the Valley of the Nile.” It was in fact the first great running boom, and one of the most fascinating periods in the whole story of the marathon.

MY FAVOURITE RACE: THE EDINBURGH TO GLASGOW ROAD RELAY

(A huge amount has been written about this event, which used to be the ‘Blue Riband’ of the pre-Christmas road racing season. Sadly the last E to G took place in 2002.) First, Brian McAusland’s introductory comments to the extensive E to G section in his excellent website: scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot “The Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay was the best and most prestigious race in the Scottish Athletics Calendar second only to the National Cross-Country Championships of Scotland. Many would say that it was the best bar none. Simply put it was a relay race starting in Edinburgh and finishing in Glasgow. It had eight stages, each of a different length and was held on the third Sunday in November each year. If that’s all it was, then it was nothing special BUT: It had been going since the early 1930’s and that made it unique; It was an invitation only race and limited to twenty clubs.

The clubs started talking about the event from the start of September, club teams were selected from the shorter relays in October and most clubs, when I started running in it, had their own E-G trials which went by the board after the Glasgow University Road Race appeared on the scene and the Allan Scally Relays latterly were also used as trials for the race.

Places were hard fought for and stages were allocated according to arcane rituals – some clubs ran their team weakest first and tried to work their way through the field, some used to run their best men first and fairly often if a club only had one or two good athletes they just ran them first to give them a hard race! I seem to remember Strathclyde University running Frank Clement and Lawrie Spence first and second and then the team finished nowhere. I stand to be corrected on that one.

It was unique in that you were often running blind and could not see the runners ahead of you. Runners were often/always running for their team mates and it was the only really club team contest on the calendar. One of my own best performances was when I picked up four or five places on the fifth stage – but it was all down to Ian Donald on the previous stage running blind all the way and just when he got some runners in his sights, he had to give me the baton.

One of the races of which I was most proud was taking the baton on the seventh stage and picking up from sixteenth to fifteenth (the first fifteen teams were automatically in the race the following year) by switching about the road to get the best line through bends, hiding from the view of the Law runner in front when he looked back and so on.

And it was the grandest affair you could imagine. When I started, it was organised by the News of the World newspaper – the race was also known as ‘The News of the World’ to the older guys – who provided nine buses (one for each stage and one for the stragglers, limousines (I mean Rolls Royces and Bentleys) for the officials and a slap-up meal for one and all in the Ca d’Oro Restaurant in Glasgow after the race.

Oh, aye, and the results of the various stages were available on the day as the race progressed – e.g. the results of the first stage were available at the start of the third, of the second at the start of the fourth and so on. Even when austerity hit the race standards were lowered as little as possible – e.g. buses were reduced in number from nine to four each to cover two stages of the race, when the NoW removed its sponsorship in 1967 the programmes were still well produced, results were available on the day and a meal was served up for the Presentation in the Strathclyde University Staff Club through the good offices of Alex Johnstone.

Latterly sponsorship was by Barr’s of Irn Bru fame, courtesy of Des Yuill, programmes were skimpy in comparison and the meal was a roll, a biscuit and a cup of tea at Crown Point – but THE RACE WAS THE THING.

Times were compared, post mortems were held and traditions were set and maintained for generations of runners. Stories were legion – e.g. every club had a Man Who Walked In The E-G. Vicky Park’s was Albie Smith on the fourth stage, just overwhelmed by the occasion; Clydesdale’s was Norrie Ponsonby (who said on the following Tuesday that he was going to retire from the sport all weekend until he realised that folk would just say “who’s Norrie Ponsonby?”); Greenock Glenpark’s was Ian Hopkins; and the greatest of them all was future Scottish Athletics great John Robson who, when very young and inexperienced, allegedly threw the baton into a garden halfway through the third stage when ESH were leading. The story ran the length of the other clubs who were still racing and wild and inaccurate rumours were rife about various things that might have happened until word came through that he was back in the race, persuaded ‘by four big shot putters from Edinburgh!’. (That was inaccurate too!) Supporters could get so carried away by watching the race that they forgot the runner who had just done his stint and drove away leaving him shivering! A special kind of race.”

By Brian McAusland

Next, brief accounts of the 1986 and 1987 E to G races.

“1986 was my final really good run in the Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay. Paul Dugdale (Motherwell) won the first leg and Graham Crawford was once again fastest on Stage Two. However Chris Hall and Simon Axon had given Aberdeen AAC a good start and Jim Doig (British International orienteer and marathon representative) raced into the lead with the second-fastest time on Stage Three, losing only four seconds to Massachusetts Select’s R.Ovian. Although Ray Cresswell lost a little ground on 4 (Craig Hunter fastest for ESH), Graham Laing moved up again (second-fastest to Alastair Walker of Teviotdale, and Fraser Clyne battled back into the lead (ESH’s John Robson fastest). Mike Murray ran really well to extend the lead to 22 seconds (American J. Marinilli fastest).

Although I was worried about my main Stage Eight pursuer being the very talented young star (and last leg record holder) Andy Beattie of Cambuslang, things could hardly have gone better. Being give a special gold baton could have been a jinx, but I took off hard into a definite headwind.

After about three miles, Doug Gillon shouted out “23 seconds and not closing”.

Before long I saw my good friend Jim Doig peering anxiously over my sweaty shoulder and then relaxing to say, “Colin, you’re running brilliantly.” An exaggeration of course, but when a few years later Jim died tragically young of meningitis, I was devastated, but eventually could take a tiny crumb of comfort from having made him proud at least once.

I managed to bash on strongly to the finish, more than a minute clear, setting the fastest time on the stage. Cambuslang Harriers were second and ESH third.

Doug Gillon may well have invented the quote he attributed to ‘a bystander’, which was “If you had cut Colin Youngson’s head off in Alexandra Parade he would still have made it to the finish in George Square”! So, at the age of 39, I still got marks for apparent effort.

1987 was the first triumph in this event for Cambuslang Harriers. Ian Archibald from East Kilbride won the first stage, with Charlie Thomson (Cambus) 6th, one in front of Adrian Weatherhead (EAC). Next the Edinburgh Club’s Ian Hamer zoomed into first place on 2, although Peter McColgan was fastest for Dundee Hawkhill. Calum Murray was 8th for Cambus, handing over to A. McCartney who moved up to 3rd, behind Brian Kirkwood’s fastest time for EAC. Andy Beattie was fastest on 4 and closed the gap to the leaders to 15 seconds. Then on 5 Eddie Stewart was quickest and gave Cambuslang a 35 second lead. Alex Gilmour extended this to almost a minute (with John Robson ESH fastest on 6). Although on 7 (A. McAngus of Bellahouston fastest) Martin Ferguson EAC pulled back thirty seconds on P. McAvoy, Jim Orr with the fastest leg 8 got completely clear of Kenny Mortimer and Cambuslang finished almost 90 seconds in front of EAC.

Meanwhile Aberdeen AAC, starting a lowly 12th, gradually made progress and, now officially a veteran, I was second fastest on the last leg to gain ‘bronze’.”

Finally, my comments at the end of a very long section of E to G personal reminiscences. Between 1966 and 1999 I took part in a record number of 30 races.

How can I sum up the truly important aspects of the late lamented Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay? All your best clubmates battled to get into the team, as the club itself had to fight for the invitation to compete. Just to take part was a privilege and an achievement. Then the challenge was to conquer the weather, your nerves and the opposition to ensure that no energy was left when you handed over and that you had done your very best. Right to the end of each race, club-mates cheered you on to stave off pursuit or overtake those in front. Yes, it was extra exciting if a medal seemed possible, but self-respect or club honour was of paramount importance. The drama, the tension, the emotional and physical intensity, the bantering, the socialising afterwards – all quite unrivalled by other events. Anyone who took part in the E to G should treasure the experience. We were lucky!”

By Colin Youngson

Finally, SVHC President Alastair Macfarlane’s E to G memories – My Favourite Event.

“Having suggested that I might wish to provide an article for the Newsletter on my favourite race the Editor has me searching my memory banks. It is now over two decades since I ran a serious race but probably like most people there are still some races which are still fresh in the memory. And there are others which are immediately dispatched to the rubbish bin, so enough of them!

Having competed at every distance from 120 yards to the marathon I suppose I have a wide range from which to choose but I have selected an event rather than a race. The event is the much-missed Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay, probably unknown to many of the current generation of runners. The E to G was a relay race for club teams of 8 runners starting in Edinburgh, running along the A8, passing through such beauty spots as Broxburn, Bathgate, Airdrie and Coatbridge and finishing in George Square Glasgow. The first race in the series was held on the 26th of April 1930 and the final event on November 24th 2002.

My early running career meant that it was 1973 before I was able to get a taste of the E to G and I was fortunate to be able to take part in all the races up to 1983. This was no ordinary relay race and no ordinary club could take part. Participation was by invitation and only the top 20 clubs in the country could take part. So there was great competition among clubs to be involved in the ‘News of the World ‘ as it became known, after the race sponsor.

And there was huge competition within clubs to make the 8 man team, with clubs using races like the Allan Scally Relay, the Glasgow University 5 or club trials to select teams. Having selected the individuals there was then the task of deciding the running order as the legs varied in length from 4.5 miles to 7 miles. The strategies varied but most clubs would turn out their best runners on legs 2 and 6, the two longest stages while leg 3 being the shortest, would go to the weakest man.

The coach and team manager of my Springburn Harriers team, Eddie Sinclair, a former Scottish 3 mile champion always wanted his team to be well up early on so the first leg was given to a solid dependable runner. Having run the first leg several times I can say the pressure and atmosphere is intense in the extreme probably because all the clubs are still closely bunched and aspirations of most clubs are still very high. In fact I would probably say that in over 50 years in the sport I have never experienced pressure and atmosphere quite like it.

Having done reasonably well on the 7th leg in my first outing in 1973 I was given the first leg the following year and did well to finish 4th behind two sub 2.18 marathon runners in Colin Youngson and Willie Day, and Commonwealth Games Gold medallist Jim Alder. And that experience was called on in the 1976 race when I again was given the first leg and was able to produce one of my most satisfying performances to win the leg with Colin Youngson second. I can still remember running along Queensferry Road in the leading group with Colin leading and knowing I would win this!

1976 became known as the John Robson race. John was one of the very finest 1500 metre and cross-country runners Scotland has ever produced but, mainly because at that time he was very young and inexperienced, he chose that day to have possibly his worst ever run. He was handed the short 3rd leg by his club Edinburgh Southern Harriers, who were probably favourites to win the race. He took over in 3rd place, moved smoothly into the lead but then, not having his best day, decided mid race that he had had enough, stopped running, threw the baton into a field and sat down at the side of the road.

This was clearly a major crisis for his club and his team mates who were yet to run. However after a combination of persuading, cajoling and eventually threatening, John was persuaded to retrieve the baton and start running again. His time for the leg is recorded as 32.47 while Lachie Stewart on the same leg ran 22.03. ESH had slumped from 3rd to 19th and it is to their credit that the remainder of the team improved to finish in 8th place.

Having experienced the high of leading in the first leg in 1976 there was a totally different experience for me 3 years later. I ran the 6th leg, the longest at 7 miles from Forestfield to Airdrie. With a weaker team Springburn Harriers weren’t doing so well and I had a long wait for my team mate to appear. I eventually took over in 20th place of 20 teams! I managed to turn a 15 second gap on the 19th team into a 16 second gain as we finished 18th, definitely not one of my favourite memories. My final appearance came in 1983 when I finished 16th on the first leg and the event itself came to an end in 2002 and is still missed by most people who had the pleasure of taking part.

By Alastair Macfarlane

RUNNING LITERATURE

(I wonder which more recent running books have inspired younger readers? Please email to recommend them.) Like many of my generation, I own a considerable number of books about athletics. In fact, I read about the topic long before I became a runner myself. Back in the 1950s, I used to get several comics a week, and of course two characters stood out as superstars.

The Great Wilson (of The Wizard) was a mysterious black-clad figure who followed a strict regime of diet and exercise and became a multi-talented world-beater at anything from sprinting and distance running to breaking the long jump record over a pit of fire, flying a Spitfire during the Battle of Britain and climbing Mount Everest. I treasure a rare copy of The Truth about Wilson by W.S.K. Webb, published by D.C. Thomson & Co. Thanks to the invention of charity shops, I have three ‘Hotspur’ annuals, featuring Wilson. If you google britishcomics, you will find several sample adventures to read or print out.

Alf Tupper, The Tough of the Track, was the other figure that nowadays would be termed iconic. Although I was a middle-class lad who went to a state grammar school (non-fee-paying!), somehow I had no difficulty identifying with this determined eccentric who lived off fish and chips, trained very hard after a tiring day’s welding, and time and again managed to defeat a succession of snobbish university runners and poisonous class-conscious officials.

A kind friend lent me his extensive collection of ‘Victor’ comics and I photocopied rather a lot of Alf’s adventures. In addition I obtained a dozen ‘Victor’ annuals; and a complete set of the actual comic saga which finishes with Alf Tupper winning the marathon at the 1970 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games on the very same day that Ron Hill set a world best time at that same venue! Once again, several tales are available at britishcomics.

In 2006 Brendan Gallagher published Sporting Supermen (The true stories of our childhood comic heroes) and I would urge anyone interested in sporting nostalgia to buy that through amazon.co.uk. Another recommendation is Victor – The Best of Alf Tupper (published in 2012) Indeed quite a number of the books I intend to mention in this article are cheaply available, although others are very hard to track down and far too expensive, even for unrepentant saddos like me!

My first memories of watching (or listening!) to athletics were from 1954: the first four minute mile and Chris Chataway outsprinting Vladimir Kuts at the White City. Naturally, I read Roger Bannister’s First Four Minutes as soon as I was able.

After that, newspaper reports about the 1956 Olympics, Derek Ibbotson’s world record, the 1958 Commonwealth Games and Herb Elliott’s exploits.

Then in the late 50s, while browsing through the stock in Aberdeen Public Library, I came across Knud Lundberg’s The Olympic Hope, a fascinating tale about a fantasy version of the 1996 Olympic 800m, with chapters on the background of each finalist and a metre-by-metre, thought-by-thought account of the final. Years later I found it again and promptly photocopied the lot!

The films of the 1960 Rome Olympics and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics (now available on youtube!) were terrific. Neil Allen wrote two very good ‘Olympic Diaries’ about these. Chris Brasher was another wonderful athletics journalist, if rather emotional!

Shortly after Tokyo I began running increasingly seriously and was able to borrow books from Alastair Wood and Mel Edwards. Olympic hero Peter Snell’s No Bugles No Drums was very enjoyable; as was Murray Halberg’s A Clean Pair of Heels; and the incredible Gordon Pirie’s Running Wild. Ron Clarke’s autobiography The Unforgiving Minute was excellent, as was his The Lonely Breed, about great distance runners of the past. Then there was David Hemery’s Another Hurdle.

After the joys of watching every day of the 1970 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games I was delighted to pick up a marvellous little book by Derrick Young called The Ten Greatest Races, which started with Ian Stewart’s recent 5000m triumph, and then focused on Wooderson, Zatopek, Bannister, Peters, Chataway, Elliott, Abebe Bikila, Clarke and Ryun.

My interest in the history of running was developed further by Peter Lovesey’s Kings of Distance; and Cordner Nelson’s Track and Field: the Great Ones.

The list goes on nearly for ever. Here are some of my favourites, in no particular order. Zatopek the Marathon Victor by Frantisek Kozik. Tinged by communist propaganda but still a great story about an incredible individual. • Brendan Foster by Brendan, helped by Cliff Temple. • Ovett: An Autobiography by Steve, helped by John Rodda. • Barefoot Runner by Paul Rambali (about Abebe Bikila). • The Marathon Makers and 3.59.4 by John Bryant. • Marathon and Chips by Jim Alder. • The Long Hard Road (two volumes) by Ron Hill. • Wobble to Death by Peter Lovesey (a detective novel set in Victorian times, featuring an epic Six Day Race for ‘pedestrians’.) • The Iron in his Soul by Bob Phillips (about Bob Roberts, an outstanding 400m racer). • The Road to Athens by Bill Adcocks. • Four Million Footsteps by Bruce Tulloh. • From Last to First by Charlie Spedding. • Paula: My Story So Far by Paula Radcliffe. • The Universe is Mine by John Emmet Farrell. • Running High by Hugh Symonds • Running my Life by Donald Macgregor. • Born to Run by Christopher McDougall. • The Lore of Running by Tim Noakes. • Running by Thor Gotaas (the ultimate history of the sport). • Scottish Athletics by John Keddie (SAAA centenary). • Runs will take place Whatever the Weather by Colin Shields (SCCU centenary).

In addition there are good books on Eric Liddell, Sebastian Coe, Steve Cram etc etc right up to the present day. Since the 1980s running boom (concentrating largely on the marathon) several good American journalist/runners have published interesting work, especially Kenny Moore. It is well worth finding out what is available for free download on the internet.

One novel I particularly like is Once a Runner by John L Parker Jnr, which is based on the author’s experiences while training at the University of Florida with Frank Shorter, who went on to win the 1972 Olympic Marathon. The book is mainly about a miler’s quest to beat a champion who seems suspiciously like John Walker, the 1976 Montreal Olympic gold medallist. Parker also wrote Runners and Other Dreamers and, just last year, Again to Carthage. Both are recommended, although the latter (which is mainly about an attempt to run a very fast marathon) for my taste goes on too much about scuba diving! If you like those books, google the author for an interesting recent interview.

Roger Robinson is one of the finest athletics writers. He was a contemporary of Aberdeen’s Mel Edwards at Cambridge University and went on to run the International cross-country championships, first for England and then New Zealand. He won the masters division of the Boston and New York Marathons; and won world masters championships in cross-country and on the roads in the M40 and M50 sections. Dr Robinson is Emeritus Professor of Literature at Victoria University of Wellington. Roger’s running books, which I recommend unreservedly, are eloquent, intelligent, witty and well-researched. One has just been republished: Heroes and Sparrows: a Celebration of Running. Then there is the beautifully illustrated 26.2 Stories of the Marathon; and the marvellous Running in Literature.

The latter provides for me half of this article! It is about running as described by famous historical figures like Homer, Thomas Hardy and James Joyce; the history of cross-country and marathon running; and finishes with an invaluable list of modern running literature.

One chapter has the title: “Running Novels – The World Championship”. The Semi-finals include thirteen books, mainly focusing on fictitious Olympic Games. I will only mention three. Knud Lundberg’s The Olympic Hope, which I discovered in Aberdeen Library so long ago. Bruce Tuckman’s Long Road to Boston, which I am finding difficult and expensive to buy. I lack the modesty to refrain from mentioning the inclusion of my own Running Shorts – a sequence of stories about the experiences of ‘Scottish runners’ (i.e. me) in youth and age, success and failure, over a variety of surfaces and distances. This text is available to read on scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot

Most of the Finalists are quite cheaply available. 13: Brooks Stannard, The Glow is a quirky, dark thriller. 12: John Owen, The Running Footman (very rare), is set in 18th Century England. 11: Peter Lovesey, Wobble to Death, has been mentioned previously, as has 10: John L Parker Jnr’s Once a Runner. 9: Bill Loader, Staying the Distance is the tale of Tigger Dobson, a working-class Northern English runner who overcomes self-doubt and a social inferiority complex to win an international 5000 metres. (Loader wrote another good book Testament of a Runner about his life and times, mainly as a sprinter in the 1940s.) 8: Paul Christman, The Purple Runner (expensive, unless you want the Kindle download) is set on Hampstead Heath, where so many Londoners train and race. There is a range of interesting runners, including a mysterious fantasy athlete, a cross between Wilson and Steve Prefontaine! 7: Pat Booth, Sprint from the Bell (very rare) is a New Zealand novel about a dedicated runner with an inspiring coach, striving to be the first man to break 3.50 for a mile. 6: James McNeish, Lovelock, is ‘a skilled, highly professional bio-fiction on the life and inner perplexities of Jack Lovelock, who won the 1500m at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in world-record time’. Roger Robinson praises the book, but states that the suggestion that Lovelock later committed suicide is wrong. 5: Tom McNab, Flanagan’s Run is ‘an energetic and engrossing tale of an imagined coast to coast footrace across America in 1931.’ It was a thoroughly justified best-seller – and written by a prominent Scottish coach too! 4: Patricia Nell Warren, The Front Runner features a passionate gay love affair between a track coach and his star athlete, as they prepare for the Olympic 10,000m. 3: Alan Sillitoe, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner is a small masterpiece concerning a troubled seventeen year old Borstal boy who finds release through cross country running but struggles to cope with authority. 2: Brian Glanville, The Olympian is about the rise of a club quarter-miler to the status of Olympic 1500m contender. The book is rated very highly as genuine literature with real insight. 1: Tom McNab: The Fast Men is a story about runners set in the American Wild West. The book has a wonderful variety of historically-based characters and is ‘a novel of vivid imagination and passionate truth about running.’

And of course there’s more. Amazon recently sent me The Runner’s Literary Companion by Garth Battista, which includes top-class excerpts from American writers – and all for £2.69 including postage! I expect to continue reading about running until my eyesight becomes even worse than my legs are now.

By Colin Youngson

ATTITUDES TO AFRICAN DISTANCE RUNNERS

Recently I watched the Great North Run Half Marathon on television. The London Marathon winner, Kenya’s Mary Keitany, won clearly in a very fast time, defeating Olympic 5000m champion Vivian Cheruiyot and two other Kenyans.

Mo Farah, tired after a long season, had to make a big effort to win the GNR. The Olympic marathon silver medallist, Feyisa Lilesa from Ethiopia, was third, with Japanese and American athletes fifth and sixth. Intriguingly, two New Zealanders, twin brothers Jake and Zane Robertson, were second and fourth. Jake lives and trains in Iten, Kenya, while Zane is based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The enthusiastic crowd near the finish in South Shields applauded every runner, regardless of speed or skin colour. When, after the race, Jake Robertson proposed to and was accepted by his Kenyan girlfriend, Magdalyne Masai, who had been fourth in the Women’s contest, the onlookers were ecstatic.

I started thinking about African distance runners and how, until the 1960s, they hardly featured in world class stamina athletics; how they came to dominate so completely; and how, recently, some non-Africans have started to compete strongly with them – such as the marvellous Scottish athlete, Calum Hawkins, who was 9th in the Rio Olympic Marathon and 4th in the London World Championship Marathon.

Back in the early 1990s, Brendan Foster’s company (rather amazingly) persuaded a number of star professional athletes to compete in an annual Road Racing Festival in Aberdeen, over one mile or 5k, round a hilly little tarmac surface in a park; or later on, up and down Union Street. Autographs collected by my sons and myself included: Steve Cram, Peter Elliot, Brendan Foster, John Treacy, Dave Moorcroft, Liz McColgan, Yvonne Murray, Zola Pieterse and Sonia O’Sullivan; and also outstanding Africans like Ismail Kirui, Benson Masya , Khalid Shah and Moses Tanui (the 1991 World 10,000m champion and 1993 Half Marathon World Record Holder with a time of 59.47).

It was Tanui versus Masya (who won the Great North four times) that fascinated me. They were running the 5k and the Duthie Park loop included a nasty steep little hill. Sadistically, I spectated from the top of this obstacle and observed a range of world class competitors panting up the slope. However Tanui simply glided up with no apparent effort before easing away to win in record time. It was running, yes, but not as Aberdonians knew it!

So, what were the origins of African distance running; how did they come to dominate; and what is the situation nowadays? Naturally I checked on what Roger Robinson, a frequent contributor to this publication, had written in his articles for “Running Times”.

BEFORE BIKILA: Glimpses of Africa’s early running history Running Times “Footsteps” column, by Roger Robinson, November 2009

I just got home from my first trip to Kenya. For anyone who cares about running, a visit to Kenya is like going to Italy for the art. I met Olympic medallists Catherine Ndereba and Paul Tergat on their home turf, bumped into four-time Boston winner Robert Cheruiyot shopping with his small daughter, and watched an exuberant children’s race that maybe contained some future champions.

African running today is vibrant, but its early history is patchy and little known. So here I offer a first jog over the ground. Running, like human life, began in Africa. The young female fossil from 3.5 million years ago who is famous in anthropology as “Lucy” was a perfect bipedal, her runner legs exactly like ours. Unearthed in 1974 in Ethiopia’s Afar Highlands, at that altitude she would have had great oxygen capacity, too.

In the wild our human stamina compensated for our lack of sheer speed. The stroppy elephant we encountered one dark Kenyan night could have galloped faster than our vehicle could reverse, but our ancestors could jog for days in pursuit of a hunted animal, or run to battle, as the Zulus did when they surprised the British in 1879. Their King Chaka reputedly could run 100 miles in 24 hours.

The first record I have found of a competing African runner is in a London newspaper of 1720. A black servant was narrowly beaten by a “Coffee-House Boy” in a race “three times round St James’s Park” (about 4 miles), for the huge stake of 100 pounds. He is not named, but was precursor of a great tradition.

Next came the two Tswanas, Len Tau and Jan Mashiani, who ran for South Africa in the 1904 Olympic marathon in St Louis. They were in town as performers in a Boer War exhibit at the Louisiana Exposition, but in their first marathon placed ninth and twelfth. The Tswana tribe migrated five hundred years earlier from East Africa, which might explain it. (Floris van der Merwe researched their identities in 1999.)

Some great Africans of the early 20th century are overlooked because they competed in the colors of France, like Algerians Boughera El Ouafi and Alain Mimoun, Olympic marathon champions in 1928 and 1956.

French results in the International Cross-Country Championship are dotted with North African names. Mimoun won four times. The first was A.Arbibi of the Racing Club of Algiers, 12th in 1913, 26th a year later. Arbibi came back to place 6th and help France win in 1923, a remarkable but forgotten career.

The Kenyan phenomenon began not when Kipchoge Keino beat Jim Ryun by the biggest margin in Olympic 1500 history in 1968, as everyone believes, but with another neglected hero, Maiyoro Nyandika, who placed 7th and 6th in the Olympic 5000 finals of 1956 and 1960.

In the 1960s, too, a German-born coach, Walter Abmayr, and an Irish schoolteacher priest, Brother Colm O’Connell, began to foster the astonishing running talent they found in Kenya, with results we now witness every week. “Training is the only excuse I accept for missing Mass,” said Br O’Connell. In 1960, too, came African running’s dramatic emergence from the shadows, as Abebe Bikila (Ethiopia) and Abdesselem Ben Rhadi (Morocco) dueled in the torchlight along Rome’s Appian Way in one of history’s most significant Olympic marathons. Africa had arrived.

The Ethiopia/Kenya Running Phenomenon; How running has responded to East African dominance is a credit to the sport

“Roger on Running,” Running Times, March 19, 2014, by Roger Robinson

The big spring marathons are just ahead – Rome (March 23), Paris (April 6), London (April 13) and Boston (April 21). One absolutely safe prediction is that almost all the top places will go to Ethiopia and Kenya. One small geographical area, about 1/60th of the total of Africa, will be utterly dominant in a major sport practiced ardently all around the globe.

In 2013, there were 149 male marathon performances faster than 2hr 10min. Eighty of those were by Kenyans, 47 by Ethiopians, plus eight by Eritreans and Ugandans, from the same region and similar ethnicity. (My tally includes one Kenyan now a Qatar citizen.) That’s 134 out of 149, and leaves only 15 sub 2:10s done by other runners (including Dathan Ritzenhein).

The same ratio prevails until you go quite deep. In the 2013 merit rankings compiled by All-Athletics.com, only nine of the top 100 men are not East African. From 101 to 200, there are only 14 from other places – Japan, Brazil, South Africa, Mongolia, Italy, and Boulder, Colorado (Jason Hartmann, ranked 194). From 201-300, the ratio is still 69/31. Of the best 300 men in the world today, 246 are East African. With the women, while the ratios are less extreme, they are moving closer to the men’s every year. This may be stating the obvious, but that doesn’t mean the obvious is not worth thinking about. These are statistics without parallel or precedent. No globally popular human activity has ever been so dominated at elite level by people from such a relatively small region. Italians are good at singing, but not 90% of great singers are from Italy. South Americans are good at soccer, but the equivalent to running would be if the final sixteen teams in this year’s World Cup were all South American.