Henry in the 1985 Tom Scott race.

A RUNNING COMMENTARY.

HENRY MUCHAMORE

( Club Athlete,Coach and Journalist.)

( Reflections on Life and Athletics from 1938 to2020)

CHAPTERS:

Prologue: Reaching the start line:

- A birthday bike for the Olympics 1948 London,

- Run Rabbit Run 1950

- Winning Ways 1952 (Helsinki)

- Belonging to a club QPH.1954- Rome)

- Running after the kids 1964-1968 (Olympics Tokyo /Mexico)

- Rugby for Fun and Fitness 1972 -1976 Olympics (Munich/Montreal

- Denholme Straw Race, London Marathon 1980 (Moscow Olympics)

- Haddington ELP, 1984 to 2012( Olympics LA; Seoul;Barcelona;Atlanta)

- Too many miles on the clock 2000-(Olympics: Sydney; Athens;Beijing)

- Arthur to the rescue 1990

- Coaching Young and Old 1986 -2020 Olympics Rio 2016 ? Tokyo2020

- Following the Games

- Time to hang up the Whistle, and Watch! 2020.

- Epilogue: How far to the Finish Line?

- SCOTLAND AT THE GAMES 1986 to 2018:

Commonwealth Games: ; 1986;1990;1994; 2002;2006; 2010;2014; 2018;

Olympic Games: Sydney 2000;Athens 2004;Beijing 2008; London 2012.Rio 2016

European Games: Gothenberg Sweden

Paralympic Games 1992 Barcelona: Sydney 2000;

1.

PROLOGUE: Reaching the start line 1938

I was born in St Mary’s Hospital Marylebone, just out of hearing for London’s Bow Bells, on Wednesday 10th August 1938. Life had been tough. There were rumblings of WW2 in the near future.

The British Empire Games were held in Sydney Australia that year. It was Scotland’s lowest ever medal tally, not a single gold medal in all sports and only one athletic medal, a silver, for David Young in the Discus. There was room for improvement all round.

In September 1939 I had a baby sister, September 2nd. WW2 started the day after! Our sojourn in London was brief. Along with my sister and mother we travelled to my Grandparent’s farm in Angus, Scotland, where we stayed for 3 years. We returned to North West London for the last 18 months of the war. My father was working on the Merlin engines for the new Spitfire planes. I started school at Princess Fredericka Church of England Primary School in September 1944 when I was 6 years old. Primary school was memorable only for the boring Church services we all had to attend. Joining the Boy Scout Cubs at the local Methodist Church certainly was not, and I found I had skills that I could develop. I gained my badges and stars and qualified as a ‘Leaping Wolf’ to join the 8th Willesden Boy Scouts at the age of 11. Complete with uniform, brimmed hat and stave, I started on my Scouting journey; as the Scout song says: ‘Now as I start upon my chosen way, to be the best, the best that I can be.’

CHAPTER 1.

A BIRTHDAY BIKE FOR THE 1948 LONDON OLYMPICS.

Looking through the photographs taken around 1945 to 1950 it is clear that my sister Muriel (Marie) and I were often photographed at my father’s photo graphic club called Hammersmith Hampshire House Photographic Society, quite a mouthful. We would go there by car or on the bus and sometimes with ‘Uncle Mac’ a friend of Dad’s who was a plain clothes policeman but very interested in photography and lived very near the King Edwards Park. The evidence shows that we were used as models and told to pose for the cameras and lights. Some looking interested at models of trains, some posed in various costumes. It took us out, and we often were given small cash tokens for modelling.

My father did his own developing in the small toilet and bathroom which he had fitted out with a home-made enlarger and developing trays. On a Saturday you had to go to the loo by 7pm, or wait for at least two hours until he had finished. Sometimes, I would go to help and was fascinated to work in the amber light, and see the pictures emerge from the developer. It took time and patience.

As I approached the 10th August 1948, my 10th birthday, and It wasn’t the London Olympics that were my priority, but the thought of having my own bike! I had dreamt about being able to ride a bike, but it had been a rule that I was not allowed one until I was ten years old, and I never questioned this. It was a black single gear bike and the moment I got on I could balance.

I was off in a flash to meet up with my friend Roy Westbrooke, who had had a bike for some time. I think, if truth be remembered, I had had several trial goes on his bike that my mother never knew about. After a few days practice, we took off to cycle all the way to the old air force base at Northolt near Hanger Lane. It was the best part of 10 miles and involved crossing the busy North Circular Road. Time flies when you are young and enjoying yourself. When we started back for home the light was starting to fail. Roy had just one head lamp, I had none, but there was a cycle path. We were stopped by a policeman, who accepted our story and directed us to stay on the cycle pathway. We were met by anxious parents, but glad we were safe. My father bought me an additional present. No, not a ticket for the Olympics, but a set of lights for my bike!

By the end of 1945 WW2 was over and Britain was getting back on its feet. There was still some rationing but sport was getting back in the picture. The war had seen the cancelation of the 1940 and 1944 Olympic Games, and 1948 was to be the year of the postponed 1944 London Olympic Games. Now to be held at Wembley Stadium, less than 10 miles from our front door.

I am sure that there must have been considerable publicity for this event and I would love to say I had a vivid recall, especially about the track and field events, involving Fanny Blankers-Koen’s four gold medals (100m Hurdles. 100m and 200m plus anchor relay leg in 4 x 100m. The Dutch ‘Flying Fanny’ she was described as, by one newspaper. Plus the grimacing face of the Czech distance runner Emil Zatopek, winning gold and silver in the 10,000 and 5000 metres. Both were to become heroes for me as I grew older.

The ‘Austerity Olympics’ was the title of Jane Hampton’s record of the 1948 Olympics. She records a number of incidents in her book. One is the role of a young medical student, Roger Bannister who made a mad dash, not on the track, but to find a Union flag for the Great Britain team to carry into the stadium as the host nation. Another is the identity of the ‘handsome’ unknown athlete, clad in white who carried the torch into the stadium and lit the Olympic flame. Chosen in preference to the British world mile record holder, Sydney Wooderson, who was small, dark haired, and bespectacled, A tall fair haired, 22-year-old Cambridge medical student, from Surbiton, John Mark!

CHAPTER 2 RUN RABBIT RUN. 1950 (British Empire Games-NZ. European Champs.Belgium.)

In the May of 1950, I had a short spell in the Central Middlesex Hospital; with what was described as a ‘Grumbling Appendix’, but it came to nothing, and I was discharged fit and well.

In the summer of 1950, I was full of excitement and anticipation about going to my first Scout camp in Wales. Donnie Owen, a neighbour’s son, was enlisted to help me acquire the kit I would need, most of which would come from the recently opened Army & Navy Shop along the road, which specialised in surplus army stock. It was certainly not a rucksack, but a traditional ‘pack up your troubles’ kit bag, the sleeping bag was new as was my billy can, tin plates and camp cutlery set. We were due to leave a week before my 12th birthday, so an added bonus was to have my birthday at the camp. Parents and siblings all gathered at Paddington Station, along with 24 Boy Scouts, several Senior Scouts, a Rover Scout and ‘Boss’ Spring our intrepid Scout Master.

We were not going to have a carriage with seats, but this was the night mail train to Merthyr Tydfil. This meant that the trek cart carrying all the tents and other camping gear, could be loaded straight onto one of the rear wagons. Most of the juniors were perched on top of the mail bags, which proved fairly comfortable, and must have reduced transport costs. I am fairly certain that the senior scouts did have more comfortable transport. What happened if someone needed the toilet or felt sick, I don’t know. I do have a vague recollection that we had to change trains at Crewe and maybe that was our ‘comfort stop’ on a rather long journey.

3.

On arrival at Builth Wells a large lorry had been hired and this took all our equipment and again I think we were perched on top of the kit bags and tents. So much for current day ‘risk assessments’ and seat belts!

We arrived at the camp site on the river Wye just outside Llandidrod Wells in the Brecon Beacons late morning, and the next few hours saw the magic of setting up camp. The large brown bell tents made a circle. The camp kitchen, plus the digging of the latrines, all had to be completed before we could unpack our kit bags.

After such a long journey and the excitement of setting up camp, our first meal was provided by the Seniors. Bangers and mash never tasted so good, along with a mug of cocoa, gave a warm glow inside and outside as we sat round the camp fire. Boss gave us one of his wonderful yarns; said the Scout Prayer. We sang ‘Now the Day is Over’ and crawled into our sleeping bags.

Needless to say that on the first night there were ‘larks’ played on some of us ‘tenderfoots’, who had various initiations to go through, such as finding various objects in your sleeping bag, or being made to run outside. It was boyish fun, and thankfully I complied with the ‘tortures’, such as the cold bucket shower, and was accepted, others had a tougher time such as being boot blacked on various parts of their body, or given a mud bath down by the river when we took our morning wash.

Each patrol had their duty days which meant rising at about 6.30am, getting the fire going and the breakfast prepared. I had the honour of taking ‘Boss’ his morning cup of tea, and was allowed into the inner sanctum of his tent which actually had a proper camp bed, a lamp and looked so much better than our large tent.

Breakfast over, the site had to be spick and span before any of the day’s adventures began, which included getting sufficient wood for the fire and water from the farm.

During that first week a day out was organised to the seaside, I can’t recall exactly where we went, but I vividly recall a trick that was played on me by two of the seniors.

There was a machine that was to give you a ‘Penny’ shock; which involved you holding the two handles after putting a penny in the machine. In itself the shock would have been mild, and you would quickly let go of the handles. I agreed to have ago. However, when I put my hands on the handles, two seniors each held my hands to the handles and put about three pence in the machine. They laughed at my reaction, as they were only holding one hand each, but I can recall the convulsion quite clearly. Of course, I never complained, it was just another joke, but years later I wondered if this incident had some repercussions for events that were to happen later in the camp.

The first week of the camp seemed to whiz by, and I recall having a great 12th birthday, which included a chocolate cake, and a game entitled ‘Catch a Rabbit’.

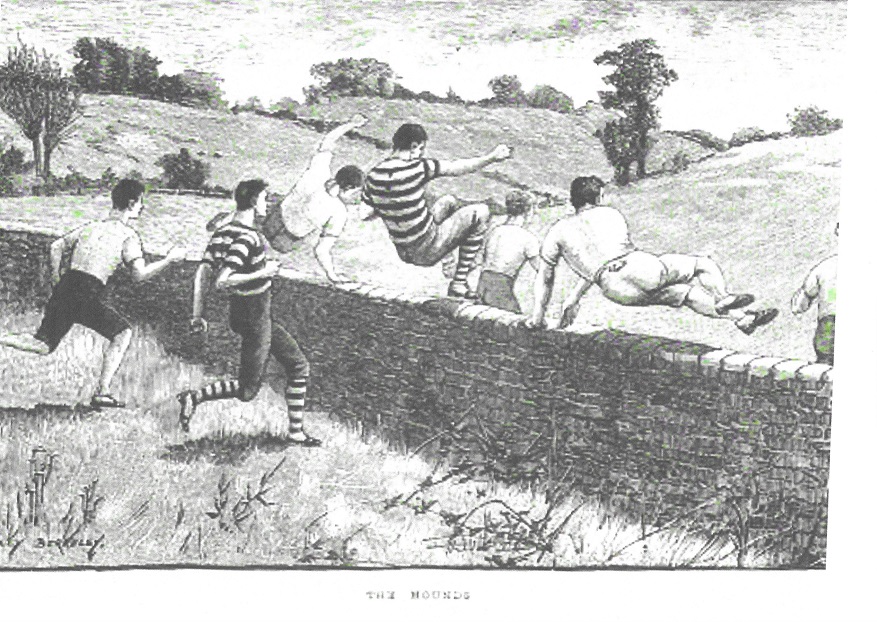

There were hundreds of rabbits in the nearby fields, and the novice scouts were given the

‘impossible’ task of trying to catch a rabbit. This game was to have a number of repercussions and consequences in my life. It was the realisation for me, that although I was not very good at ball games, I could run, and run I did, across the field carrying a small stick. It may also be that one poor rabbit was either injured or slow, because I not only caught it up, but delivered a hefty blow which killed it instantly. Picking up my trophy I came back triumphant. Much to ‘Boss’s surprise, presented him with the dead rabbit. He took one look, and told me it was no good to cook, as it had a broken gall bladder, and would have to be thrown away.

4.

The second repercussion to this event was that I had over exerted myself, and that evening complained to my Patrol Leader that I had a sore stomach. He was convinced it was just the consequence of my exertion, or maybe some camp food. The consequence was that I had severe diarrhoea for two days. The leaders then thought I had been stealing the laxative chocolate from the grub tent store. The pain grew worse, and finally after three days ‘Boss’ decided that medical help was needed from a doctor. One look at me convinced the Welsh Doctor that I needed to be admitted to hospital urgently. An old village ambulance took me over the rough field and road to the cottage hospital at Builth Wells. Acute appendicitis was diagnosed I was operated on that night.

My mother and father were notified initially by telegram and made a telephone call to the hospital. It was clear that my condition was serious, so my father set off in his black Riley Falcon saloon, registration number UF7749, to come over night to the campsite in Wales where he met up with Boss and came to see me in hospital.

Next day the situation deteriorated, and that night I hallucinated in the bed, and had what I later learnt was as an ‘out of body experience’. Whereby, I was on the ceiling of the hospital ward looking down on myself and calling out ‘I’m going to heaven to have a bath’ I obviously woke the other patients! The night nurse came with haste, to find my hands gripping the side of the bed and refusing to let go. I was given some sedation, because the next thing I knew was being taken back into the theatre to have a second operation for peritonitis, as the burst appendix had spread.

In all I spent six weeks in the hospital at Builth Wells. I remember my mother coming with my baby brother, Aubrey, who was now just six months old. Gradually I was allowed up, and visited the Surgeon and his family, to whom I will be ever grateful, as I realised later how near I was to dying.

In modern day scouting, a risk assessment would be done, especially if a child had recently undergone a hospital admission. Maybe the fun electric shock, and the rabbit chase all contributed. Maybe ‘Boss’ should have taken action sooner than he did to call for medical advice. The reality is that another 70 plus years have gone by, and I am still able to record the tale.

My father did the long trip down to Builth Wells again in early September, along with his policeman friend who we called Uncle Mac, and drove me home. I remember feeling sick on the way and asking to sit in the front of the car. I recieved a warm welcome from my brothers and sisters, as well as the scouts in my patrol, but I did not return to my new school for another couple of weeks.

My father subsequently became Assistant Scout Master for the next 9 years up to his death in 1959.

What was happening at the major athletic Games during that period?:

1950 saw the resumption of the British Empire Games held in Auckland New Zealand with Scotland winning gold in the Hammer with Duncan Clark. Alan Patterson won silver in the High Jump as did Andrew Forbes in the 6 mile event.

At the 4th European Athletic Championships in 1950 in Brussels, Britain won 17 medals 8 gold medals including Brian Shenton (200mt) Dereck Pugh (400mt) John Parlett (800mt) Scot Alan Patterson (HJ); Jack Holden won the Marathon after finishing 36th 2 years earlier at the London Olympics. Plus the men’s 4 x 400mt relay. GB’s women won the 4 x 100mt relay and Sheila Lerwell the High Jump. Emil Zatopek won both the 5k and 10k races and Fanny Blankers-Koen won the 100mt; 200mts and the 80mts Hurdles

Forty year later in 1990 I attended the Commonwealth Games in Auckland New Zealand.

5.

CHAPTER 3.

WINNING WAYS (Olympic Games 1952-HELSINKI)

With the tender loving care of my mother and the family around me,I quickly regained my strength. Dr Essex our family GP signed me off as fit to go back to school, but NO exercise until after New Year 1951. This also was to have an influence on future events. Having ‘failed’ my 11 plus exam, I learnt that I was to be in the A stream at Pound Lane County Secondary School, and although I was about a month late in starting, I enjoyed being back with both old and new friends.

Mr Palmer was the name of my form master, a kindly man who had been in the Air Force during the war, and seemed genuinely interested in his pupils. I had to start learning French. it was also compulsory for all students to do one lesson of PE (Physical Education) a day. Our PE Master was a Mr George Addy, another ex-military man from the Guards. His curt commands left you in no doubt that his ‘orders’ were to be obeyed without question.

Needless to say, I presented him with a problem, that I could not do PE until after Christmas on the Doctors orders. ‘Well that maybe so’ he said ‘but you are not sitting here watching everyone else during the lesson.’ My instructions were that I should WALK around the playground at my own pace until the 40 minute lesson was complete. This I did every day, and each day I went a bit further. How many laps could I do in 40 minutes? Towards the end of the Christmas term I even tried a little jog! By the time I returned to school in January 1951, I was ready willing and able to join the PE class.

What was really good was that I was getting stronger and fitter, and starting to enjoy school. I really enjoyed Maths and English. Miss Cosgrove was our English teacher and she would have us involved in poetry and plays. I recall being given the part of the Owl to recite in Graham Green’s The Owl and the Pussycat- Sheila Francis was the Pussycat. It was great fun and led on to my doing a lot of drama at school.

I played the part of Fagin in Oliver Twist and frightened Bill Shiran who was Oliver when I hovered over him with a carving knife when he woke to see me counting my precious jewels.

I recited a speech of Shylock from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice at the Willesden Schools Drama festival starting with ‘Senior Antonio… and ending with. …and if you wrong us shall we not revenge!’ Msr Mannete from the Tale of Two Cities was another famous role with the lines ‘One hundred and five North Tower’ in answer to question ‘what is your name’. All helped to build up my self-confidence.

In June 1951, less than a year after my operation, I was chosen to run in both the 880yds and 440 yds events at the Willesden Scout Sports (The Half and Quarter mile). Photographs of the event show me in rather baggy shorts a T shirt and a pair of Woolworth’s plimsolls. I had finished second in the half mile to a boy from the 28th. My father had arrived at the stadium just as I finished, and told me that in my next race, the quarter mile, I was to wait until he waved his handkerchief, at which point I had to shorten my stride and sprint like the wind – it was my first WIN. The following winter in January 1952, at the Willesden Scouts Cross Country Championships at Eastcote at the age of 13 and a half I won, running over 2miles, and beating boys 2 years older than me, and leading the 8th team to victory. I was to win that event five times.

6.

Looking back at old school reports, I note the following: I was 27th in the class at the end of 1951 following my late start, and was 7th in 1954 just before I left. My general subjects of interest were Maths and English, plus Geography and History. Not so good were art and science. I had special mention for my drama and P.E especially athletics and boxing. I was both house captain for Nelson House and Boys Athletic Team Captain. I was twice winner of the Willesden schools half mile championship in 1953 and 1954, resulting in my competing in the Middlesex Schools Championship at the White City Stadium in 1953, where I tripped when in the lead, just 50 yards from the finish line. In 1954, I finished fourth, but it was not held at White City that year.

My boxing career at school consisted of just 3 fights. In 1953 and 1954 I was eliminated in the first round of the Willesden Schools Championships. In 1953 by a boy called Cream, and in 1954 by a boy called Mutch. However, just before I left school in 1954, I competed at an inter schools event between a School from Stepney, East London and Pound Lane. I managed to beat the reigning East London Champion, a boy called Kemp, over three rounds. No one was more surprised than me. I was watched by Mr Jenkins the milkman I worked for, and he gave me ten shillings after the fight. However, my badly damaged nose made me decide to take the doctor’s advice and give up boxing and concentrate on my running.

In February l952 I sat and failed my Technical College exams. The most memorable thing about them was that when we finished, we were all summoned to hear the news that King George VI had died. Along with many thousands I went with our scout group to pay our respects and queued until 2am to see his coffin lying in state at Westminster Abbey. I will never forget it, as the guards were just changing, as one of the four guardsmen turned on his heels he caught his spur and it fell off onto the dais. I arrived back home at 4 am, but still got up at 6am to do my milk round, before going to school at 8.30am.

Most days I would cycle to school, and go to the running track two or three times a week to train, with Ted Hodgeman our coach. along with Martin Hine. and other athletes from Willesden. From time to time I would train at Paddington. On a regular basis they would have inter club athletic matches with clubs such as Thames Valley Harriers, and Shaftesbury Harriers. Sometimes, these events would include a cycling event, as a concrete cycle track surrounded the cinder track.

During winter months we would travel to Eastcote where the annual Willesden Scouts Cross Country Championships were held.

During my whole school life, once I was fit, I helped Mr A.J Jenkins, who owned a local dairy shop, delivering milk seven days a week, for three years. Apart from having time of to go to Scout Camps my only ‘day off’ was on Boxing Day, we delivered milk from two hand carts. I would get these from the shed at 6am, and have them loaded with the crates by 6.30am. ‘Mr Jenks’ as I called him, would make a cup of tea, and we would set off at 6.45am. I would deliver on one side. and he on the other. We would get back by 7.45am. I would then re-load the big cart before I went home, had my breakfast, and cycled to school. ‘Mr Jenks’ would do a second round after I had gone to school.

On Saturday and Sunday I would help to collect the money. Tips helped, but my weekly wage was just ONE POUND or twenty old shillings. However, back then milk was 6d a pint that’s equal to 2.5 new pence.

7.

On several days when the ice was bad, there were accidents. I still have the scars on both my wrists where I fell with bottles in my hand. I had my own form of weight training. I could lift three crates of 20 pint bottles, onto the cart.

Just before I left school in July 1954, Mr Jenks asked me to help him with a mid week round. This was unusual. It was the first Wednesday in June. In those days it was known as Derby Day. Thousands would go to Epsom Downs to watch the world’s most famous horse race. It meant skipping school, or ‘hopping the wag’ as we called it. However, I agreed on two conditions. One: that I could go with him, and also he would give me my wages to have a bet. He did both. On arrival once we had parked the car, we found ourselves a spot on the heath, near to the stands, opposite the one furlong to go post. The Bookies had their stalls. It was time for the first race. Prince Monalooloo was walking round in his African head dress shouting ‘I gotta a Hos!!’ ‘Jenks’ had a bet and won! We celebrated by buying a bowl of jellied eels. I did not get carried away by the razzamatazz, but waited for the big race. A young 18 year old jockey had hit the racing world. He was Lester Piggott, He was rather tall for a jockey, but could ride like the wind. Other famous jockeys of that era included Gordon Richards and Eph Smith.

Lester was riding an outsider called ‘Never Say Die’, it was 25 -1, but I backed it with five shillings each way (25p) that was half my wages! It WON! I picked up over £6. This was more than my father earned in a week! I bought Mr Jenks a bowl of jellied eels for a shilling, and took the money home and gave it to my mother. But I had to keep quiet at school as to where I had been that day!

My mother used the money, together with her sixpenny weekly Provident Club, to buy my first suit to start work at A.W.Aylett and Company, Chartered Accountants in Victoria Street London on the Monday after I left School on the Friday.

I collected my last wage from Arthur Jenkin’s Dairy, along with some good ‘tips’ on the Saturday.

I just had the Sunday as my ‘Gap Day’ between leaving school, and starting work!

1952 HELSINKI OLYMPICS:

My interest in athletics, as a sport, was becoming more serious, and Helsinki was the venue of the 1952 Olympics. For me, the outstanding athlete was the Czech distance runner Emil Zatopek. He won the 5000 mt in an Olympic record of 14m6.6s; The 10,000mt. in an Olympic record time of 27m17s.and the 26.2mile marathon in 2hrs 29m19.2s, a world record.

Britain’s Gold medal hope, Roger Bannister, came a frustrated 4th in the final of the 1500mts.

Zatopek went on to do the ‘double’ of 5k and 10k at the 1954 European Championships in Brussells, and started to prepare for 1956, when the Olympics were to be held in Melbourne, Australia.

I bought a treasured book on Emil Zatopek, with pictures of both his training and racing. In more recent times I have read of his true ‘endurance’ when he suffered under Communism for his political and personal beliefs. Also in 1954 the British Commonwealth Games were held in Vancouver Canada. There was one particular Scottish athletic gold medal that will be remembered not for the winner, but the brave loser.

(* ‘Endurance’ Rick Broadbent; ‘Today we Die a Little’ Richard Askwith.)

8.

The British Empire and Commonwealth Games of 1954 in Vancouver, Canada, is always remembered for two rather spectacular events.

‘The Miracle Mile’ brought together the track heroes of the year. Roger Bannister of Britain, who in May became the first man to break the four minute mile barrier and John Landy of Australia who smashed the barrier by 2 seconds just one month later. Now the titans of the track would duel in the final of the mile. Bannister had won the European 1500 mt title in Berne, Switzerland in 1952 after a tactical struggle which demonstrated his superior speed over the last 200metres of a race.

From the gun Landy ran the only way he knew, all out. Bannister a master of pace judgement, was not tempted to go with Landy and at the start of the last lap Landy had a comfortable lead, it seemed impossible task, but step by step, Bannister’s enormous stride pulled Landy back. With 150 yards to go, on the crown of the final bend, Landy turned his head to see where Bannister was, and swoosh, Bannister went past and headed for the tape. There was nothing Landy could do. Bannister had won what many called the ‘Miracle Mile in which both men broke the magic four minute mile barrier.

The other memorable event of the Games, came at the very end, the final event, the 26.2 mile Marathon. It had been incredibly hot in Melbourne, and the Marathon was being run in the middle of the afternoon. It was planned to finish in front of the royal box where the Prince Phillip, the Duke of Edinburgh, was to greet the finishers. The long time leader, by some distance, was England and Great Britain’s world record holder, Jim Peters, the gold was his for sure, or so it seemed. The heat had taken its toll on all the athletes, including Peters. When he came into the Stadium, he only had 385 yards to run to the finish. He was exhausted, and started to wobble and stumble. Officials knew they could not help. Visions of the 1908 Olympic marathon in London came to mind, when a tiny Italian named Dorando, was in a similar plight. Helping him to the finish, resulted in disqualification. Peter’s did not want the same to happen to him, so he staggered on, but it was in vain. A blue vested runner came into the stadium. Joe McGhee of Scotland, was first over the line. Jim Peters was picked up and given urgent first aid. He never ran another marathon. However, he was given a meritorious award by the Duke of Edinburgh for his brave run

The European Games of 1954 saw Great Britain win 2 other gold medals plus a silver and bronze. Thelma Hopkins won the high jump. Jean Desforges won the long jump. Chris Chataway took silver behind Vladimir Kuts in the 5k and Frank Sando the bronze behind Emil Zatopek in the 10k.

In the 1958 Commonwealth Games in Cardiff,Wales. Ian Black was Scotland’s hero, with a double in the swimming, but nothing to show for the athletics team medal wise. A young 19-year-old Scot, Mike Lindsay came 4th in both shot and discus. He went on to pick up Scotland’s only athletic medals, both silver, in the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth Australia.

Perth, was the home town of golden boy, Herb Elliot, who won the mile at the Australian championships in under 4 minutes and would go on to dominate middle distance running up to the 1964 Olympics, never having been beaten in a mile or 1500mt event in his career.

9.

.CHAPTER 4. BELONGING TO AN ATHLETIC CLUB Q.P.H. 1956-1960.

After winning my second Willesden Scouts Association Cross Country Championship in 1953 at Eastcote, the HQ of the Queens Park Harrier (QPH) athletic club, I was approached by the Club Secretary Frank Pettit, who asked me if I wanted to join the club,and train on a regular basis with other young athletes, at Paddington and Willesden athletic tracks. I asked my father, who agreed. Training sessions were on a Sunday morning, and Thursday evening at Willesden, plus Tuesdays at Paddington if I could make it.

To begin with Sunday was OK. However, in February 1954, I attended a Billy Graham Campaign meeting at Earl’s Court in London, and became very involved with the local church on Sundays.

About the same time, I had read a book entitled ‘A Man called Peter’ that included the story of Eric Liddell, the famous Scottish athlete and rugby international, who was selected for the 1924 Olympics in Paris. He was selected to run in the 100mts, for which he was one of the favourites. However, as the heats were to be run on a Sunday. He refused to run based on his religious beliefs, but went on to win the 400mts in a world record time. A story that in 1981, became a famous film ‘Chariots of Fire.’ Contrasting the life of a young Jew Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell.

For several years as a Youth and Junior athlete, I adopted this philosophy, and was influenced to consider training for the Congregational Church ministry. This included conducting Church Services at many churches in the Middlesex, and South of England as a Lay Preacher.

In consequence, with hind sight, I recognise, that whilst I trained regularly during the week and raced on Saturdays, I missed out on the longer club pack runs on a Sunday morning, and maybe missed much of the endurance work needed for my main events, which were the one mile and half mile.

As a youth I gradually reduced the QPH club Youth half mile record to 2m 6s and the Junior club record to 2m.02s when I finished 4th in my heat of the London Championships, held at the famous White City Stadium at Shepherds Bush. Although I twice did the double (Mile and Half mile) at the Willesden/Brent Championships as a Youth and Junior, getting a podium place in the Middlesex Championships was frustrating, with 4th place being my best. The Junior record stood for several years until a neighbour’s young lad Mike Bunday broke the magic 2minute barrier. My best race over a mile came when I was 18 in 1956, when I ran 4m 29s at Chiswick Stadium.

Cross Country running was my favourite event. I continued my regular run for the Scouts championships, winning five times. It was for QPH that I had my best runs, with a second-place team medal in the 1956 Middlesex Club Championships, and a team winning medal in the ‘Bert Ives’ trophy. I was both QPH Club Youth and Junior Cross Country Champion from 1956 to 1960.

Perhaps the highlight of my time with QPH came when I was selected for the famous London to Brighton Road relay. It was only open to the top 20 clubs in the south of England. QPH had won the right to be there with success in the Leyton to Southend Relay in 1956. I was selected to run the penultimate 11th leg over 4.5miles. My father came to support me and took photos.

10.

It was a memorable day. I was handed the baton to run the 4.25mile penultimate leg, from Elmar Salnajs, in 12th place, and handed it over to our final leg runner, Tom Harwood, in 10th place,who went on to finish 9th. I ran the 4th fastest time for the leg, and set a Junior record for the leg. QPH were awarded the ‘Meritorious Award medal’ for the club best performance outside the top 3 clubs.

However, although we competed in the event for the following 2 years in 1957 and 1958, we never reached the same standard, and, to my disgust in 1958, I ran the slowest leg! ‘The dust of defeat!!

In 1956 I reached my 18th birthday. With it came the documents requiring me to serve my country for 2 years for National Service. I considered applying for dispensation, as I was hoping to go to College to train for the Christian Ministry. However, under the influence of our local Minister, I decided to apply as a conscientious objector.

This required my attendance at a formal Tribunal in London, to which I had to give evidence of my beliefs, and produce witnesses to testify on my behalf. The basis of my argument was that, I did NOT object to National Service for my country, but not for military service. The outcome was, that they accepted my case. I was ordered to undertake my National Service in farm work, food distribution, or hospital work. The first two were impossible; so with the Country under a threat from a Poliomyelitis epidemic, I was taken on as an Orderly/ Porter, (Dog’s body), at the local fever hospital, just 5 miles away from my home. The system was shift work of 8 hours (6am-2pm; 2pm-10pm; 10pm-6am). I did a bit of everything on the wards, assisting with various therapists, plus, looking after the mortuary! I landed the graveyard shift of relief night worker, which involved 2 night shifts each week plus 3 day shifts. Although this gave me more time for my studies, which included opportunities for some night time reading, it did nothing for my physical fitness, and training routines. Running had to take a back seat, at least for the moment.

I finished my National Service at Neasden Hospital in November 1958, just after my 20th birthday. My GCE A level exams had not gone too well. I had to find a job. During my time at Neasden I had taken particular interest in helping the Physiotherapists rehabilitate people with polio. I sought a position at a rehabilitation centre near Woking in Surrey. The Rowley Bristow Hospital had a variety of patients with various injuries and illness that made them incapacitated. Many lay in plastercast jackets. My main task was to attend to their basic needs, including ensuring they did not acquire bed sores. I had accommodation on site. I had bought myself a 50cc NSU motorbike, (advertised by Emil Zatopek). I came back to my home in NW London, 25 miles away, quite frequently on my days off. I managed to fit in the odd run round the common, but it was winter, and I spent long days on my feet, lifting heavy men.

Winter turned to Spring in 1959. I came home for a few days at Easter and learnt that my father, despite having retired at 65, had taken on another job as a caretaker. He had bought a mini moped bike, similar to mine, but with the engine located at the rear, made it heavy for him to lift over the high doorstep, My mother was worried ,and wanted me to tell him to give it up. He was delighted to be mobile and had some extra money. On my return to Woking, he came down the stairs to see me off on Friday 10th April . As I waved goodbye, I never realised that it was the last time I would see him alive. He had spent the weekend helping at the Scout’s Jumble sale, and mending my sister’s bike. On Sunday he had been involved with his photography and had gone to bed as usual. On Monday 13th April, he had a severe coughing fit, which led to a heart attack and almost instant death. He had been a heavy smoker all his life, as many were in those days.

I had been for an early morning run, and whilst showering, I heard banging on my door. I opened it, wrapped in a towel, to be told by an insensitive porter. ‘You are needed at home, your Dad’s died.’

11.

I returned instantly to home and joined my shocked mother and family. I spent the week organising the funeral along with our Scoutmaster Ernest ‘Boss’ Spring .He arranged for the Scouts to provide a Guard of Honour at his funeral the following Friday.

My Father had been my biggest supporter to my running, and losing him dampened my enthusiasm for competitive athletics for while. In August 1959 I celebrated my 21st birthday with some local friends, in the same room, albeit redecorated, as my father had died in.

OLYMPIC GAMES 1956 MELBOURNE and 1960 ROME. BRITISH EMPIRE GAMES 1954 & 1958

Russia was now starting to have a strong influence in athletics. Amongst their newest athletes was a soldier named Vladimir Kuts. His tactics, in both the 5k and 10k events, was to keep putting in surges, which upset the rhythm of other athletes, including Britain’s Gordon Pirie who finished 2nd and Derek Ibbotson who was 3rd in the 5000mts final. His tactics proved successful and he won both the 5k and 10k titles in Olympic record times. The USA took 13 gold medals, including all the sprints. An Irish athlete, Ron Delaney, was the surprise winner of the 1500mts leaving Britain’s hero Roger Banister, among the also rans. Britain did have a winner. Chris Brasher, he had been a pacemaker to Bannister in his epic 4 minute mile in Oxford in 1954. He won the tough 3k steeplechase but not without, initially, being disqualified. The British appeal was successful. John Disley took the bronze medal. He subsequently, went on to help Brasher set up the London Marathon in 1981

Eight Olympic records were set on the track plus a world record by USA in the 400mt relay. Seven Olympic and one world record were set in the field events. The standard of athletics was rising dramatically. Was this through more structured and systematic trainng methods or other means?

The 1958 Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, Wales is rather forgotten from an athletic point of view. There was not a single Scottish medallist on track and field. The nearest was a young 19 year old based in USA, Mike Lindsay a member of my London club QPH who finished 4th in the Shot and Discus. Scotland did have success in swimming diving and boxing.

The Willesden Chronicle, had a back page sports report mentioning my winning the QPH Junior Cross Country Championship. This appeared just beneath a headline report on local Neasden golden girl, Judy Grinham, who broke the world record for the Breast Stroke at the Games.

CHAPTER 5 UNIVERSITY GAMES 1960-62

After leaving school in July 1954, I attended regular training at King Edward’s Park in Willesden and Paddington Recreation track in Maida Vale. I did not start keeping any record of my training until I wrote a 10 week schedule for training in 1956, and a daily diary of training and racing in 1957. I still have the rather battered log book, which I maintained up to 1965.

As previously mentioned, coping with the shift work hours of my National Service, and the death of my father, disrupted any regular or serious training. I note from my diaries, that I seldom ran further than 10 miles in any endurance training, and most of the track work was intervals over various shorter distances. Most of the cross country races were 3-6 miles with the exceptions being the Southern Counties over 7.5 mile and the senior national 9 miles! However during this period, I won the club Junior cross country championships in 1959/60 season, and had my best season on the road culminating in the London to Brighton relay run for QPH.

12.

My concentration now was linked to my application to go to New College Theological training for the Congregational Church ministry. As well as my studies for New Testament Greek and Church History, I conducted services at local churches on Sundays and had to prepare for these as well as my work as an accounts manager for a local engineering firm. With the help of local tutors, I managed to gain entry to new Collage for the start of term in October 1960.

It was a totally new experience, I had had a car, a Riley Kestrel with pre select gears and although I had managed to save some money, I was reliant on a grant and a bursary from my church. The car had to go, but I did get back to doing some running on nearby Hampstead Heath with a couple of other students. In February 1961 I competed in the London Theological Colleges Cross Country Championships at Northwood Hills over 4.75miles. After leading for most of the way, I was overtaken at the finish by two runners from the Spurgeon’s Baptist seminary. One being an international 400mts athlete called Ted Sampson. My time was 26m55s. My training on Hampstead Heath was more recreational, and my energies had to go into my studies. In the summer vacation of 1961 I worked in a large Psychiatric Hospital near Eastbourne, and had some enjoyable runs along the south coast, but again mainly for therapy as a contrast to the work I was doing.

My second year at College included taking on responsibility for a small church at Hook near Basingstoke. This involved travelling down every two weeks on my 75cc Scooter that I had bought. The college did have a squash court, and I enjoyed a regular game with fellow students.

1962 was a tough year. I was doing better with my studies and was enjoying my Pastoral work at the church. However, I started to question my belief in my vocation. I spoke with the Principal and he agreed that I should take a year out. It was difficult, and I took up doing some paid Youth Work. That led to my becoming a Residential Child care Officer in a Working Boys Hostel in Southhall, Middlesex. I found that this proved to be a more satisfying career. I was invited to return to New College after a year out but I decided to train as a Child Care Officer for the new London Borough of Hounslow. The time out also led to my taking up rugby for nearby Osterley Park Rugby Club, mainly for the Xtra B side.

ROME OLYMPICS 1960.

The Rome Olympics had many highlights. The events that stood out for me were the events that I was most interested in, albeit they were in metric measurements, the 800mts, 1500mts and 5k. My hero was, and still is, Herb Elliot from Perth Australia. He was the current world record holder of the mile 3m54.2s ran in Dublin. Elliot was never beaten over the 1500mt or the mile and won the 1500mt Olympic title with consummate ease, in a world record time. However, a fast-talking Coach from New Zealand, had a small squad of 3 athletes that would light up tracks throughout the world in the coming decade. Arthur Lydiard watched his favourite protege Murray Halberg win the 5000mts. Then, he told a hesitant Peter Snell, that he could win the 800mts by biding his time. So it proved, Snell snatched victory in the last few strides setting a new Olympic record. Arthur’s day wasn’t finished. The Rome Coliseum had seen gladiators fight. That evening they witnessed the first African gold medallist from Ethiopia, Abebe Bikila win the marathon running in bare feet, in an Olympic record time of 2hrs 15m16.2s. Taking the bronze medal that evening was Kiwi, Barry Magee, one of Arthur’s most dedicated athletes. I had the pleasure, in 1990 at the Commonwealth Games in Auckland, to meet with Arthur Lydiard and some of his ‘Boys’ and published those interviews in the Scottish Veterans magazine. (See attached)

Britain’s only success in Rome was Don Thompson nicknamed ‘The Mouse’ who set an Olympic record of 4hrs 25m for the 50k walk.

CHAPTER 6 RUNNING AFTER THE KIDS 1964 -1970.

I first met my wife to be in 1959, when I was doing my National Service at Neasden Fever Hospital. I was asked to take a Christian Fellowship Group at the hospital. She attended my 21st birthday party with two other nurses. After my Dad died in April 1959, we became friends, but it did not last beyond the new year when her sister got married. I was able to help as taxi driver. In April 1960 her father was killed in a motor bike accident and this brought us together again for a short while, but I was going to College and she was off to Glasgow to do her midwifery training.

Over three years was to pass before we met again. The hand of fate took us to the Alter in 1964. I was taking up my post a Child Care Officer with Middlesex County Council. As well as my official title I also assumed a more practical one when we were blessed with the arrival of our son. Middlesex County Council was to be divided up and joined with the new London Boroughs. I was now working for the London Borough of Hounslow. I was offered the chance for formal Home Office 2 year training in Child Care which I under took in Ipswich from 1966 to 1968, by which time we had a ‘pigeon pair’ a son and daughter. The training involved several practical placements in residential and community based settings. The final of which was in the east end of London in Poplar. Although we had a small flat in Kilburn to return to, we managed to save enough for a deposit on a mortgage on a house in Wokingham. I had to travel each day to my area office in Chiswick.

During this time I had managed to keep fit by playing rugby for the Ipswich College and after we moved, I played for Reading Rugby Club. I also had the odd game of Squash to help me keep fit.

Two healthy youngsters kept me on my toes, as well as running groups for teenage boys who were in the care of the Local Authority. I recall taking them on a training course to North Wales, where they were offered climbing, sailing and various survival activities, some of which had me in fear of my life!

In 1970 I applied for a specialist post linked with the Juvenile Court, providing programmes for such youngsters. However, I was not successful. Having completed my two year return contract with LB Houslow. I was successful in applying for a post as Child and Family specialist worker in City of Norwich. This delighted my wife as this was the home town of her mother, who had supported us throughout our early years. We sold our house in Wokingham, and moved to Sprowston on the outskirts of the city in April 1970.

COMMONWEALTH GAMES 1962;1966; OLYMPIC GAMES 1964;1968

Two men, not permanently resident in Scotland, were responsible for holding Scotland’s head up in athletics at the Commonwealth Games In 1962 in Perth, and in Jamaica in 1966. Mike Lindsay was born in Glasgow but was at School in Marylebone in London took two silver medals in the Shot and Discus just missing out gold by 3cm in the Discus. In Jamaica in 1966 it was Morpeth based, Jim Alder who achieved the 6 mile bronze and Marathon gold medal, overcoming extreme heat conditions.

14.

In Tokyo Olympics of 1964 the USA dominated the track in all but two events. Those were the 800mt and 1500mt double won by NZ’s Peter Snell. Billy Mills (USA) a Sioux Indian was the surprise winner of the 10k. Mary Bignal Rand set a world record in the Long Jump, clearing 22ft. for first time. Lynn Davies (GB) a Welshman surprised both favourites in the Long Jump. Abebe Bikila again won the marathon, this time wearing running shoes, in a world record time of 2hrs 12m11s. Ken Mathews of GB won the 20k walk.

CHAPTER 7 RUGBY FOR FUN AND FITNESS1970 -1978.

As you enter the outskirts of the City of Norwich, the sign says ‘Welcome to Norwich a Fine City’. And so it was. I settled in to the Norwich City Children’s Department, and felt warmly welcomed by all the staff. With the help of other professionals in Health, Education, Housing and Welfare Departments, we set up regular meetings with local officials, to monitor vulnerable children and families. I also set up joint training programmes, which covered these aspects, which was entitled in those days as ‘The battered baby syndrome’.

As a family, my wife enjoyed being near her mother and the children had a loving grandma to spoil them from time to time. Such was the success, that I was asked to take on the function of Training Officer for the City. I developed staff development programmes in conjunction with the staff from Norfolk County and the Universities of East Anglia and Cambridge. However, Local Authority reorganisation was afoot. I had been there before, in 1964, it proved to my advantage.

In 1974 it was different. The County dominated the City and I faced the prospect of ‘Demotion’, in the sense that I would be subject to the Norfolk County structures. I chose to take a chance to look elsewhere, and was offered the post of Senior Training Officer with the new Calderdale Authority, which took over from the old West Riding of Yorkshire.

My wife was not happy with prospective upheaval, and neither were the children and in particular, my mother in law. Looking back I wonder whether I did the right thing.

Sport wise I played squash, and the occasional games of rugby. Plus the odd run on Mousehold Heath. I had lost a lot of fitness generally. After a delayed move north, we were close to the Yorkshire Moors, the Bronte country and the fells. I actually tried the odd fell race, but found it harder coming down than going up!! We bought a Welsh Springer Spaniel, and she gave me a lot of exercise, mostly walking. I also took up golf, and had the odd game with a colleague. We had a large garden, and keeping it in order, including growing vegetables, was also good exercise.

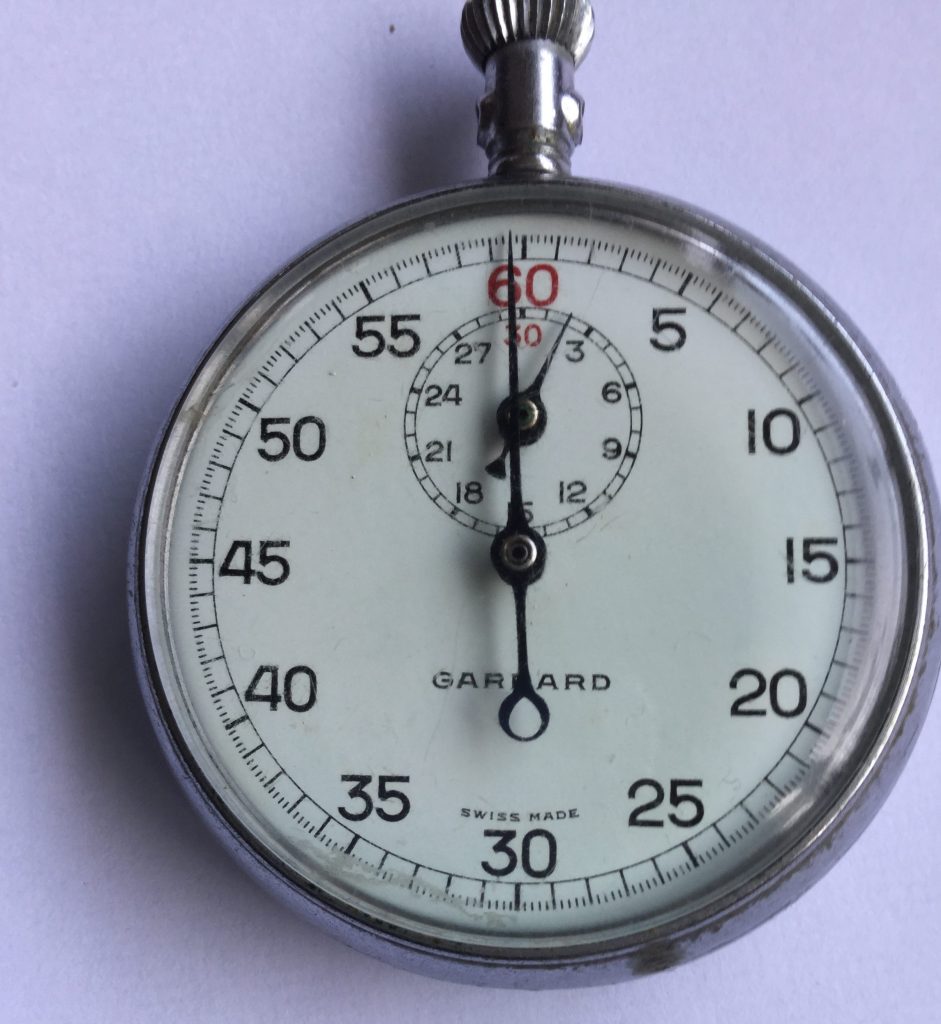

My wife was a qualified Health Visitor. On a course she attended in Huddersfield, she met up with Madeline Ibbotson the wife of Derek Ibbotson, former world mile record holder. I was in the crowd at the White City Stadium in July 1956 when he broke Landy’s mile record clocking 3m57.2s. My hand stopwatch recorded the same time and I did not reset it for months after!

My wife accepted an invitation for us to go to dinner with the Ibbotson’s at their home in Huddersfield. I took with me a copy of his brief autobiography including his time in the RAF. I hoped he would sign it for me. The evening turned out very different from what I expected. He asked if he could keep the copy I had brought, as he did not have one of his own. What could I say but- ‘Of Course!’ It was mid 1980’s and ‘Ibbo’ as he was affectionately known, was rather portly, but an excellent squash player, and an agent for Puma sports shoes and clothing. Half way through the meal, he disappeared to watch a soccer match and returned in a very angry mood, as one of the players he had sponsored had blacked out the logo on his boots. Our dinner party was not the delight I had hoped for, but I admired his running when he was at its best in the 1950s.

In 1978 I started to suffer from a strained back. I was overweight, and sought medical advice. I was told that I needed a special test, which involved putting dye into my spinal column, to identify the blockage. However, there was a long waiting list.

We chose to have a holiday in Scotland, and took a large flat near Oban. We visited most of the tourist spots. I played tennis with the children as well as going for walks. On our penultimate day, we visited Fort William, with the initial intention of climbing Ben Nevis, but it was a poor day, and there had been a lot of rain. My wife and the children were not keen on the idea, but I decided to try going on my own with Bella our spaniel. I set off with great intent, but quickly realised that I was not going to get to the top, so cut off at the lake, half way up. The rain came on, and we seemed to find the muddiest route back, but we made it, and I felt a ‘high’ that I had not had for ages.

On our return home, I found a letter from Bradford Royal Infirmary with an appointment for the spinal check operation. On telling he surgeon what I had done on holiday, he simply put down his pen, and told me he would not continue the investigation. I was to take up running again. His predication was that I would succeed or become permanently disabled in five years. I chose to go back to some running. My competitive athletic life lasted until 1993, after needing knee surgery.

It was about this time in 1979 that Chris Brasher, one of Bannister’s pacemakers, came back from participating in the New York Marathon, to announce that he was going to set up the London People’s Marathon in 1981. This became my incentive to train regularly. I met up with a member of Bingley Harriers, Gerry Spinks, an international veteran runner at the local sports centre, and subsequently, I joined Bingley Harriers, and ran in a couple of races. The first of which, was a One Mile UP HILL race in which I managed to run 5m 55s!

I also persuaded a neighbour Dave Allen, to run with me on the local roads and moors. Although I found a new lease of life in running, my work was frustrating. I had taken on the post of District manager for Halifax, at the request of the Director, but it was not satisfying me. I had for a long time yearned to go back to Scotland, my mother’s country and where I spent early days of my life.

I applied for a post in the Scottish town of Musselburgh, East Lothian, which was part of Lothian Region. All the staff were qualified, and I was stepping into the shoes of a highly respected leader. My interview was in December and following a successful meeting with the local Director I was asked to start in January 1980. There was much to consider, not least my children’s schooling and my wife’s post as a district Nurse. Despite the drawbacks, I said yes, and life changed dramatically in 1980. Another upheaval for the family! Was I making the right move?

BRITISH EMPIRE AND COMMONWEALTH GAMES 1970; 1974;1978

OLYMPIC GAMES 1972,1976;1980:

The decade from 1971 to 1980 was, in many ways, the high point of British Athletics. Edinburgh hosted the 1970 Commonwealth Games at the newly built Meadowbank Stadium, Scotland came away with a total of 8 medals. Four Gold, 2 silver and two bronze. Rosemary Wright won the women’s inaugural 800mts. Rosemary Payne the women’s discus. Lachie Stewart had stirred the Brave Hearts on the opening day by winning the 10k. It was the 5k race that was the most thrilling, Australian World record holder Ron Clarke was very much the favourite. He was out sprinted on the last lap by two Scots and an African. Ian Stewart just held of his fellow countryman Ian McCafferty. They heard the stadium erupt. Jim Alder the hero from Jamaica, took silver in the marathon. William Sutherland took bronze in the 20k walk as did Moira Walls in the high jump.

In The Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1974 it was a very different story with just one silver medal for Rosemary Payne in the discus. At The Commonwealth Games 1978 in Edmonton Canada, it was the Scottish sprinters that raised the Scottish flag. Alan Wells won the 200mt and the silver medal in the 100mt. Then, together with Cameron Sharp, David Jenkins and Andrew Mc Master, won the 4 x 100mt relay. John Robson won bronze in the 1500mt, as did Bryan Burgess in the High Jump, and Chris Black in the Hammer.

The Olympic Games of 1972 in Munich will be remembered for the terrorist attack on the Israeli team. However, there were many sporting highlights. In the pool Mark Spitz from the USA won 7 gold medals, and broke 7 world records. On the track, Valeri Borzov of Russia won both sprints. USA’s Dave Wottle came from last, with 200mts to go, in the 800, to win in what they called, the ‘Wottle Throttle’. Finland’s Lasse Viren fell in the 10k, but got up to win and also won the 5k. Kenyan, Kip Keino won the Steeplechase, and Ugandan John Akii-Bua won the 400m hurdles.

In 1976 in Montreal, Lasse Viren did the double double, in the 5k and 10k. Sadly the African nations boycotted the Games over South Africa’s regimes. Britain’s highlight came in 33year old Mary Peter’s from Northern Ireland, winning the Pentathlon. Possibly the outstanding moment for most people, was the Rumanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci’s perfect 10, never before achieved!

1980 saw the Olympic Games come to Moscow, but this time it was the USA that boycotted the Games. Scotland’s Alan Wells won the 100 mts, and was just beaten in the 200mts. The duel between Seb Coe and Steve Ovett, was the highlight of the middle distance events, with Coe the favourite for the 800mts, being beaten by Ovett, and then the reverse came in the 1500mts, with what was called ‘Coe’s Revenge’

CHAPTER 8 OXENHOPE STRAW RACE TO LONDON MARATHON 1981.

It took over a year for us to sell the Bungalow in Denholme. As the school year in Scotland was different from that in England, both of my children had only a 4 week summer break, rather than 6 weeks, before starting their new schools. It also meant I had to find lodgings. We were given temporary accommodation in August, on the banks of the River Tyne. This interim, provided me with an opportunity to continue my running. The Observer newspaper announced that they were backing Chris Brasher’s idea for a ‘People’s Mass marathon’, based on the New York model, to be held in the Spring of 1981. It would be the longest distance I had ever run 26.2miles! I was travelling back to Yorkshire after work on a Friday, and returned on a Monday morning. Dave Allen and I continued our regular runs on the moors. I managed to get up to 10 -12 miles in about 60 to 90minutes. As summer came, I was able to explore the East Lothian coast line. After we moved into our temporary flat in Haddington, I met up with a couple of locals who had also been successful in getting an application to run London. One was a Insurance salesman, another a window cleaner and a younger guy who owned a small café in the High Street, and had run the distance for charity. We started to meet regularly during the week, and on a Sunday morning, when we did our ‘Long’ runs of 18 to 20 miles, taking 2 and a half to 3hrs.

On my last week-end before moving to Haddington, Dave Allen and I joined up as a team to compete in the Oxenhope Straw race, over 3 miles, in which between us, we had to carry a 50k bale of straw, and drink a half pint of beer at each mile marker. It was very warm, but out of 150 starters we finished 9th.

17.

My membership of Bingley harriers was short and sweet, but I had made links with several members including, Terry Lonergan a sub 2h 20min marathoner. He was a salesman for new running shoes and sportswear. I agreed to bring some to Scotland and would get 20pc on anything I sold. I did ok once I started to make contacts in East Lothian, but ended up buying several pairs for myself! At one stage I had about 20 pairs of shoes, including spikes and studs for road, track, and cross country courses. I tried various events, including fell and hill races, plus cross country and road races, as far afield as Manchester in the west, and Darlington in the north east, and a variety of events throughout Scotland. I met up with the SVHC (Scottish Veteran Harriers Club) when I took part in the World Veteran Road Championships in Glasgow in August 1980. I ran in the 10k event, and finished in 39m40s but ended up in hospital with heat exhaustion.

From January to December 1980, I had run 500 miles, an average of about 50miles a week. I had got my weight back down from over 12 stone to 10st 12lb, almost the same as when I was 21. I was now 42 years old! In October, I ran in the SVHC Half marathon and finished in 1hr 25m, with which I was pleased, as it meant that I could set my target for London in March 1981 at under 3hrs.

As I was not travelling back to Yorkshire once the bungalow was sold, I joined Edinburgh Southern Harriers (ESH) and competed for them in various cross-country events, together with my new training partners, John, Alistair, Murray and Joe. We had regular training sessions off road, at the Tyningham estate, home of the Duke, as well as the roads around Haddington.

I also went to train at Meadowbank Stadium, on the tartan track which was used for the 1970 Commonwealth Games, and where they would host the 1986 Games. The facilities to train were great, on the track, as well as quiet country roads, forest glades, and sandy beaches.

By the end of December 1980 I had run over 1000 miles since I restarted running in October 1979. I spent Christmas 1980 with our extended family in Dorset, and trained every day over Christmas.

Over the next three months, I had eight races to prepare for London, over road and cross country, and apart from minor injuries to my leg ,I felt very fit, having clocked 61 minutes for a tough 10mile race over 2 laps, with a steep hill. The London Course was going to be twisty but flat. I also ran the Scottish East District CCC, and the Carnethy 5 hills race in February, so I felt the only thing that was going to catch me out would be the distance, so we set to, and planned a 2- mile run on a Sunday morning with John and Alistair. My last race before London, was to compete for the ESH Vets team in a 4 x 5.6mile relay. I ran the 4th leg in 32 m 56s. I felt I was ready. Many of my solo training runs, especially in the country, or near the sea were with my faithful spaniel Bella. She just loved running.

LONDON MARATHON 29TH MARCH 1981.

Looking back as I write in March 2020, the London Marathon was due to have started for the 40th time, but due to the Corona virus (Covid 19) that has hit the world, it has been postponed until October. I had put in well over 1000 miles of training, but did not properly taper in the 2 weeks before. We travelled to London on the Friday, and I met up with Chris Brasher that evening. He asked me to organise a small group of runners to meet the favourites, Joyce Smith and Hugh Jones, for a publicity run over Westminster Bridge at 11 am on Saturday. We arrived, but none of the favourites, so we jogged over the bridge for the photographers. That photo was to appear on the front page of the Sunday Observer on the morning of the race March 29th 1981!

18.

The weather was overcast with light rain, ideal for the 6000 plus starters from Greenwich. I pressed the button of my sport watch as we crossed the official start line and steadily got into a comfortable stride. We passed the Cutty Sark at 6 miles, and crossed London Bridge at 12 miles and ran round the Isle of Dogs at 18 miles then came back through the Tower of London at 20 miles with its covered cobble stones, along the Embankment, where the crowds grew thicker, ran down the Mall at 25 mile, finally we crossed in front of Buckingham Palace, to reach the finish line in Birdcage Walk. My two brothers Gordon and Aubrey had followed the race and taken several photos. As I came to the finish, I could see that the clock above the Gillette sponsored gantry, still showed 2 Hrs 5? minutes. I pressed my wrist stop watch, which showed 2hrs 56m46s, and I had finished 1062nd place. I could see a runner in a red and white striped vest (QPH), and it turned out to be Neville Rees, one of my old QPH running buddies.

My three companions all ran well, and we celebrated that evening before returning to Edinburgh the following day. A new friend from the OU featured on BBCTV, in a distressed state. I was determined to try again and do better. Also to see if I could help organise a similar event in Edinburgh in 1982.

OLYMPIC GAMES;1984 LOS ANGELES 1988 SEOUL

In 1984 the Games went to LOS ANGELES, USA. Daley Thomson was the toast of the British team retaining his Decathlon title, with a world record performance. Seb Coe again took silver in the 800mt, but retained his 1500mt title. A young Steve Cram reached the final, but it was a backward step for Steve Ovett, who ended up in hospital. Mike McLeod finished 4th in the 10k, but was subsequently promoted to the bronze medal after a drug test on the third placed Russian.

In the women’s events USA’s Evelyn Ashford, was Queen of the sprints. Tessa Sanderson and Fatima Whitbread (GB) battled for gold and silver medals in the javelin, and Wendy Sly ran a well judged finish, to take silver in the 3k. Phil Brown took the silver medal in the 50k Walk. Daley Thomson retained his Decathlon title, and with it set a new world record with 8847 points.

In !988 The Olympics came to Seoul the capital of South Korea. The sprint events for both men and women were the headlines, but for very different reasons. Americans Carl Lewis and Florence Griffiths Joyner (Flo Jo) were favourites for the 100mts. However, in the men’s final, Canada’s Ben Johnson spoiled the show by taking gold in a world record time of 9.79s. Lewis was second, and Britain’s Linford Christie dipped for the bronze. Just two days later Johnson was disqualified for drugs being found in his system. In the women’s final, Flo Jo set her long standing OR of 10.54s.

Both Lewis and Christie were promoted. Lewis was beaten again in the 200 by fellow countryman Joe Deloach, but the result stood this time. Christie anchored the GB squad to a silver medal in the 4×100 relay. Peter Elliot took the bronze in the 800m and silver in the 1500m. Mark Rowlands was 3rd in the 3k SC. It was very brave run by Scotland’s Yvonne Murray in the 3k, that earned her the bronze medal, having made her bid 450 mts from the finish, but beaten by two drug suspects from Russia and Romania. Subsequently the Russian was proved a drug cheat, but Yvonne never received her deserved silver medal. Liz McColgan also had a fine race, taking the race from the front but again beaten by a Russian sprint on final lap.

Liz and Yvonne were two great Scottish female athletes of that era and earn their place in both the Scottish and UK Sporting Hall of Fame. Fatima Whitbread again took silver in the Javelin.

19.

The Commonwealth Games of 1982 in Brisbane. Scotland brought home 10 athletic medals, 3 gold one silver and 7 bronze. Both gold medals were won by Allan Wells in the 100 and 200mts Fellow sprinter Cameron Sharp took bronze in both races. Both men added a bronze medal in the sprint relay. Meg Ritchie won gold in the discus. Anne Clarkson won the silver medal in the 800mt. Chris Black won bronze in the Hammer as did Graham Eggleston in the Pole vault. Sixteen year old Lindsay McDonald anchored home the Scottish team in the 4 x 400 relay. Yvonne Murray had just turned 18 and finished 10th in the final of the 1500mts.

Edinburgh was the venue for Scotland’s next chance to host the Games in 1986.

Being directly involved with a major World Games has been a great experience. I had a particular interest, as I was now writing a weekly athletic column for the local newspaper, East Lothian News. I had met a local Musselburgh athlete, by the name of Yvonne Murray, and had done a profile on her for Athletics Weekly. Hence, I not only had a job as an official on the warm up area and marathon, but was able to have access to the Press Tent. On the last day of the Games, none other than the notorious Rupert Murdoch bought me a glass of Guinness! With the words ‘So, you’re the local hack, are you?’

The 13th celebration of the Commonwealth Games proved to be disappointing for athletic fans. There was only one gold medal for Scotland at Meadowbank Stadium. Liz Lynch in the 10k. Tom McKean took silver in the 800mts, Geoff Parsons also silver in the high jump. Yvonne Murray was favourite for the 3k race, but was out sprinted by two Canadian girls, and ended with a bronze medal. Bronze medals were also won by Sandra Whittaker in the 200mts and the 4 x 100mts men’s relay squad. Winning just six athletics medals in front of your home crowd was very disappointing.

CHAPTER 9. HADINGTON E.L.P.1980 -2012.

The excitement of having successfully completed the London Marathon in under 3hrs, spurred me to make enquiries as to how an Edinburgh marathon could be organised by 1982. Needless to say, Glasgow was also keen to develop a mass marathon themselves. In the meantime, my training continued with ESH. I became more involved with the SVHC in bringing events to Haddington. The outcome was the setting up of a 5 mile road race during the Haddington Festival, on the first Saturday in June 1982. I organised a Half marathon on behalf of the SVHC in August. Both events proved successful.

By the Spring of 1982 I had started 4 more Marathons, in Newcastle in August where I missed the start but ran 20 miles in 2hrs 6m; Bolton 2 weeks later in extreme heat I clocked 3hrs 9m; Glasgow in October again only 20 miles in 2hrs 9m.

In the SVHC Championships at Bellahouston in March I dipped under 2hr 50 mins. Just six weeks later, I returned to London and ran with George Brown in ESH club colours, as it was a UK National Championship, this time breaking the 2h 45min barrier. I was now 45. In the space of just 14 months I had started 6 marathons, and completed 4 in gradually improved times. Looking back, I can see that I did too much.

The prospects of an Edinburgh Tartan Marathon on 5th September 1982 were now very promising, and although I was involved initially in the promotion with Dave Farrer.

20.

I was not fit enough to race. Instead I agreed to push a woman in a standard wheel chair around the course, starting at the very back of the 3000 starters. The outcome was we crossed the line in 3hrs 49 mins, overtaking 2000 runners, completely exhausted. We raised £500 for Sport for Disabled People. However, Five weeks later, I lined up again at the start of the Glasgow People’s Marathon on October 17th 1982. There were over 7000 starters. I finished in 103rd place in 2hrs 45 mins. I had a few cross country races in November. My mileage dropped from over 250 miles per month to 165 at the end of the year and my diary notes that I had several visits to a physiotherapist.

I had an eight-month break from Marathons, then ran five in five months. Three under 3 hrs, and two under 2h 50m, including the BVAF Championship –The Flying Fox at Stone in Staffordshire.

My goal was to run under 2hrs 40m, if possible, at 6m mile pace. My target race was London 1984. However, a long-standing problem I had physically, was the subject of haemorrhoids!

My Training diary for the 3 months from October to December 1983 shows that I had ran over 600 miles in training, plus 8 races, including the World Veteran (IGAL) Road Championships in the heat of Perpignan France, where I finished the 10k in 35m44s. I was 1st V45 Scot to finish, the following day the 25k (15,5 miles), where again I was 1st V45 Scot in 1hr 35min.In both of these races I was running at my desired marathon pace of 6m mph. I had 4 XC races and a one mile TT in 5m17s.

I was admitted to Roodlands Hospital in Haddington from 5th to 12th December 1983 for the operation, but all did not go well. I had a haemorrhage, and had to have a blood transfusion.

Over Christmas, I had some very easy walks and jogs. 1st January 1984 I went with the club to line up for the Morpeth to Newcastle New Year Race (14.5miles), and clocked 90m 42s, (6m 15s per mile), finishing 507th from 3000 starters. I felt I was back on target for my London Marathon in May. From January, I gradually increased my mileage to nearly 1200 miles in 4 months some weeks clocking the magic 100 miles in 7 days. I felt I was flying! Or thought I was! From January 1st to 29th March 1984 I had 14 races, which included 2 marathons, as part of my preparation for the London Marathon on 13th May 1984, which was my planned race to run 6 minute-miles (2h36m).

I had several cross country races including the Scottish Champs in February; The Balloch to Clydebank (12.5m). Two ten mile races, including the Edinburgh Uni, 10 and the Tom Scott 10m, plus an Open Graded 1500m clocking 4m48s. On 1st April (All Fools Day)I I ran the SVHC Marathon, as a ‘Long’ training run in 2hr 56m. In honour of my mother, whose birthday was 2nd April, I had planned to run the Dundee Marathon for the British Heart Foundation. Also as a ‘Long Training Run’.

In the changing area at Caird Hall Dundee, I got chatting to Don Macgregor, the Scottish Olympian from Fyfe. I told him of my plans for London. His comment was today the forecast is for a ‘sea haar’ which with light wind make it an ideal day for a marathon- you don’t know what London will be like.- Put your racing shoes on and give it a go!!’ Wearing the BHF vest and bonnet, I started nearer the front than I had planned and at the 5,10;15 and 20 mile marks I was running at just on 6mph; Just 10k (6.2 Miles) to go! I had heard a loud speaker announce that, Don Macgregor and Terry Mitchell were battling for lead. There was only one other Veteran runner ahead of me.

I put my head down and went.! It was tough, and slightly up hill. As I rounded the last corner I could see the timing clock was saying 2h 30m? As I got closer, it was ticking away at 2hr 39 mins. I crossed the line with arms aloft in 2hrs 39m31s. I finished in 25th place from nearly 2000 starters. Don had won in 2hrs 18m but I was 2nd vet to finish and received the Vet’s award and a voucher.

21.

I returned home as high as a kite!! Surely I will achieve my goal in London!, I had also raised over £500 for the British Heart Foundation. Thanks Mum!!

Instead of resting up completely, I started the Edinburgh to North Berwick 22mile race just a week later. With my HELP pal, Joe Forte, who was 20 years my junior, and aiming for sub 2h 30m in London. We ran 18 miles in under 2hrs, plus a 10k TT in 35 mins. I ran a total of over 80 miles in the 2 weeks before London. We stayed with my brother in Watford, and we had a 36 min run on the day before London. The outcome was that I ran well for 15 miles but into a head wind and in a warm sun. At 20 miles, I had lost over 3 minutes on my Dundee times, and by the finish over 7 minutes, resulting in a time of 2hrs 46m24s. I took 43 minutes for the last 10k compared with 38 minutes in Dundee. A big disappointment as Joe had run his sub 2h30. Don Macgregor’s prediction was right! A hard lesson to learn as an athlete and a coach. Listen to your body! Recovery is crucial !!

In 1988 I was to reach my 50th birthday, and I had great intentions of doing well in my new Veteran or Masters Age group.

London in May 1984 was my 16th start in a Marathon. Only in 2 marathons had I failed to finish, due to mix ups. In 1984 I had 4 marathon plus 2 that used as training runs. In September in Glasgow and Edinburgh. I returned to Dundee in May 1985 not fully fit, and in bad weather I ran the marathon again, but this time I ran a very conservative 2h55m. I had a much more controlled year. In October I went to Dublin as an invited ‘Fast For Age’ veteran. I had the new shoes that I had won previously, but the night before the race I changed the insoles, as I knew there was a lot of concrete to run on. I started on the elite start. My 5 mile splits were on target at 5 and 10 miles going through in 59m09s. It was the same for the next 5m, just 5 seconds over 90min for 15 miles. However, the concrete section between 15 and 20 miles took its toll and I lost 3 minutes. I could feel a blister on my right foot. I was determined not to limp but at 22 miles, I had to stop. The blister was bleeding badly, and I took 5 minutes to try and repair the damage and carry on. I dropped to running at over 7 mph, finishing 2hr 53m, and having taken over 50 mins for the last 10k.

I took six months before starting my 4th London marathon, which I finished in 2h 55m. I was involved in helping organise the 1986 Commonwealth People’s marathon in June. I had a steady run in the June heat, finishing in 2h 46 min. I had the pleasure of beating Ron Hill.

The Glasgow City Link Coaches Marathon was a disaster for me. I struggled for the 2nd half and took nearly 3hr 30 mins!! I decided to have a break from running Marathons.

With my 50th Birthday year ahead my aim was to compete in NEW YORK USA in November.

In April 1988, I ran the SVHC Championship, and ran a steady 3h09m and was 1st in the V45 age group. In September, I was now 50, I ran in the NALGO ‘New York’ marathon at Whitley Bay, staying with my old QPH friend Martin Hine. I ran a comfortable 2h 52m, even paced, 1h 26m at half way. This really set me up for the NYCM. Flights were booked with HELP companions Jim Baird, running his first marathon, and 18 yo Steve Chalmers, who I had coached as a junior in the club.

We were met on arrival and hosted by anther QPH old boy Mike Dale, and his wife Mary in there New Jersey luxury home. Mike was deputy head of Jaguar cars. It was luxury, and we had a day touring the City prior to the race. I took part in the WHO Fun Run .and attended the famous Pasta Party in the evening, which was great, but I missed the last subway tube, and had to walk about 50 minutes to my back ‘pack’ digs on 42nd Street. Excited and a little too full, I did not sleep well. By 6 am I was clad in my tartan vest and shorts, off to meet the transfer bus to the Verrazano Bridge.

22.

The start was over 2 hrs away. Jim and Steven were quite relaxed, as we were near to the start. When eventually, the gun went, there was a mad rush. Our plan was to run at 6m30s pace. This was thwarted by a group of French and Italian runners holding hands, and blocking the way. Jim and I took nearly 8 minutes for the first mile. Then we ran under 6mph for the 2nd mile, to try and make up time by the end of the bridge. It was a great spectacle and experience, but the start had its effect on us. Crossing all five bridges was an added distraction. Although back on target time at 5 miles, each subsequent 5 mile split got slightly slower. By the time 18 miles came up we were reaching Central Park. I was not feeling good and told Jim to run on, while I tried to find a spot to spend a ‘penny’. The spectators were great, and not keen to see me stop, but I had to. At 2h12m for 20 miles I still had a chance to get under 2h 55m, but the legs felt bad, I was running on empty! As I reached the final corner, I could see the clock approaching 3hrs. I just made it, in 2hrs 59m59s. Whereas, Jim clocked 2h 52m a time that would have put me in 2nd place for the Masters V50 award. Steven ran well for an 18 yo about 3hrs 30mins.

On returning to Mike and his family, he gave us an incredible surprise, an individual flight in his twin seater Biplane. We saw all over NY State, a memorable trip, on what was to be my penultimate marathon.