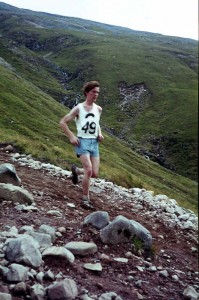

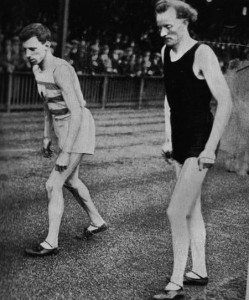

Bobby in the Ben Nevis Race.

Although Bobby Shields ran on the track and the roads as well as over the country he really loved the hills and raced on them all over the country from the Kilpatricks in Clydebank to England, Wales and Ireland. The Ben Nevis race is one of the most gruelling in the United Kingdom but if Bobby was a specialist in hill running, he was a specialist’s specialist in the Ben Race! He was placed in the top ten eleven times. He was 1st 1967, 2nd in 66, 3rd in 65, 73 and 74, 4th in 65, 5th in 70, 6th in 68, 7th in 81, 8th in 69 and 71 and eleventh in 64! Furthermore his eleventh in 1964 gave him twelve first eleven places in twelve years! Evidence enough of his ability and durability on the hills.

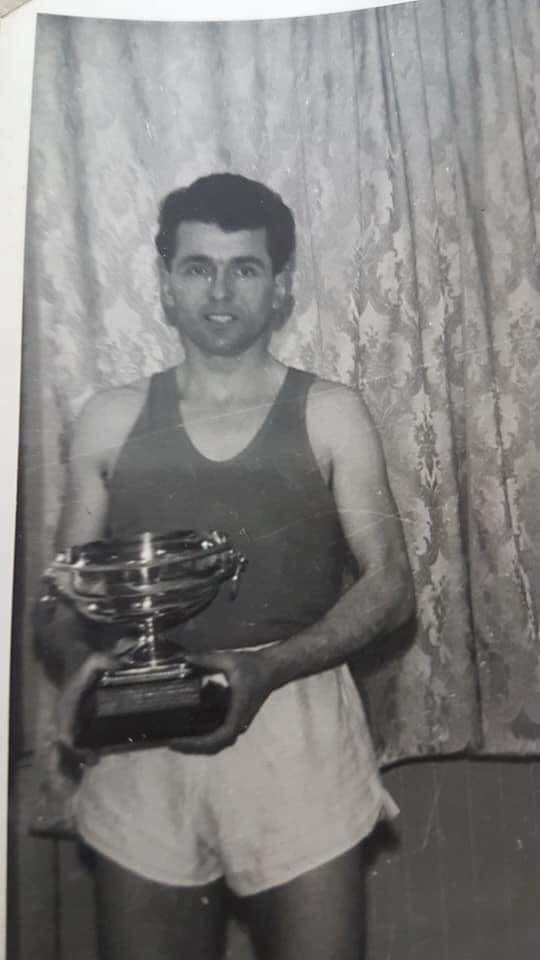

He had been a club member since the late 1950’s and within Clydesdale Harriers he won numerous club trophies:

- The JD Semple Junior Cup in 1961, 1962 and 1963 for the Under 17 Club Champion,

- the Dugald Cameron Shield in 1964/65 as Under 20 Club Champion, the Semple Merit Award in 1964/65 for the outstanding performance during the winter season,

- the Sinclair Trophy in 1967/68 presented for the Club Road Racing Championship over 5+ Miles,

- the Willie Gardiner Quaich in 1967/68 for the most outstanding performance during the summer season and

- the Hannah Cup in 1969/70 (shared with Ian Leggett) and 1970/71 for the fastest time in the club cross country handicap race.

So we know he was an excellent hill runner and a good enough club man to win trophies in all age groups over a ten year period when the club was particularly strong in his events. But it was on the hills that he really excelled.

The Early Years

Between November 1958 and September 59 Bobby was one of six very good boys to join the club – Andy McMillan, Billy McLaughlin, Iain Cooke, Ian Logie and Bobby’s twin brother Jim were the others – who made up a quite outstanding group of athletes who won team and individual races all over Scotland. Andy left to attend to his studies and became a minister; Iain turned to sprinting and then became a doctor before leaving the sport; Billy left, came back in the mid sixties, left, came back in the seventies and left again, Ian Logie took up pole vaulting with success before retiring from the sport at the end of the 60’s and brother Jim took up pole vaulting, emigrated to Canada before returning and having a very successful career as a hill runner and tri-athlete. But Bobby stuck to the running and concentrated on hill running with huge success.

Having won the Under 17 Championship three times in succession and the Under 20 Championship he was ready to run in the Senior team. This was almost exactly at the same time as Ian Donald joined the club from Shettleston and despite the age gap they would both form part of Harriers teams until 1977. They both had an interest in the hills and mountains and Ian had a great influence on Bobby.

The Hills and Fells

Right from the start however he was like many a Harrier before him in love with the hills – hill walking, hill climbing and mountaineering and of course hill running. He took to the Ben Nevis – probably the most difficult hill race in the country – immediately. Ian Donald had run his first Ben Race in 1959 when already a Senior athlete. Bobby’s first race was in 1964 and he finished eleventh, then in 1965 he was third, in 1966 second and then he won it in 1967. His record is detailed below

|

Year |

Place |

Year |

Place |

Year |

Place |

|

1964 |

11th |

1972 |

4th |

1981 |

7th |

|

1965 |

3rd |

1973 |

3rd |

1982 |

6th |

|

1966 |

2nd |

1974 |

3rd |

1984 |

8th |

|

1967 |

1st |

1975 |

123rd |

1985 |

333rd |

|

1968 |

6th |

1976 |

150th |

1986 |

370th |

|

1969 |

8th |

1977 |

5th |

1987 |

318th |

|

1970 |

5th |

1978 |

91st |

1988 |

329th |

|

1971 |

8th |

1979 |

11th |

1989 |

275th |

His best time for the event is an astonishing 1:31:58! He did of course run in almost every hill every hill event in Scotland and we can’t cover them all over a 25 year period but some of the highlights can be listed.

* Mel Edwards of Aberdeen was a good friend and rival who recalls the results between the two of them in the Cairngorm Hill Race in which Bobby won three times (1972, 1974 and 1979 when he set a record of 1:12:15), was second once (1981) and third twice (1974 and 1980). The 1979 race was particularly memorable with Bobby winning in 1:12:15 from Ronnie Campbell in 1:12:19 and Mel in 1:12:22 – three runners covered by seven seconds after such a long and hard race. He also set records almost everywhere he ran – the Maidens of Mamore is another example of that.

* On 21st August 1976 the one off Maidens of Mamore race was held over Na Gruagaichean and Binnean Mor. Bobby won in 1:43:40 with Ronnie Campbell second in 1:45:51 and twin brother Jim Shields third in 1:52:24. Clydesdale Harrier and good friend of Bobby’s Ian Donald was eighth in 2:03:44.

He was well known all over the British Isles for his prowess on the hills having raced in England and Wales and completed many feats of hill running endurance with the best runners of all time on the fells of England and mountains of Ireland. He also ran for several different clubs on the hills and fells – eight of his Ben races were in the colours of Lochaber AC, for instance, and he represented Kendal AC in England and Lagan Valley in Ireland

When the British Fell Runner of the Year competition was started in 1972 Bobby led the competition right up to the very last race when Dave Cannon from Cumbria snatched it from him. The competition involves selecting a prescribed number of races from three different categories which include short, medium and long races and adding the points so gained. On another occasion Bobby shared first place. Dave particularly remembered finishing third in the Ben Nevis in 1973 beaten by Bobby and Harry Walker, another noted English Fell Runner and winner of the race.

Not only a runner, he has also been responsible for two races that are among the most serious tests of strength in any hill runner’s calendar. The race over the 95 mile West Highland Way is now established in the athletics calendar but few realise that it came about as the result of a personal challenge between Bobby and his friend Duncan Watson in 1987 – two of Scotland’s best ever long distance hill runners. It is now in 2007 an almost over subscribed event.

He also created the Arrochar Alps Hill Race with fellow Clydesdale Harrier Andy Dytch in 1987. This one covered 21 kilometres, took in four Munros – Ben Vorlich, Ben Vane, Ben Ime and Ben Narnain – with a total ascent of 2400 metres and was used as a British Championship race in 1988.

As A Road and Cross Country Runner

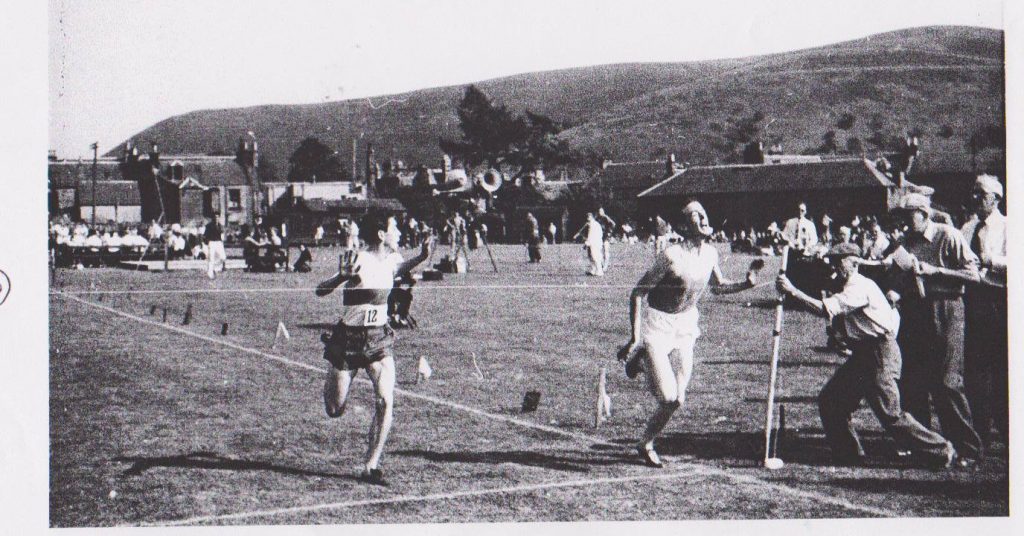

Bobby was a good club man and from his earliest days had run in County, District and National Relays and Championships, the Edinburgh to Glasgow Relay as well as in open races and the ‘classics’ such as the Nigel Barge at New Year and the Balloch to Clydebank.

In the CountyChampionships he won medals from the mid sixties when he was part of an outstanding group of Clydesdale runners including Ian Donald, Douglas Gemmell, Ian Leggett and Allan Faulds. He was also a member of teams that won medals of all colours in the Midland and then Western District Championships. The Edinburgh to Glasgow eight stage relay was the Blue Riband of the Scottish winter scene. Bobby ran in seventeen Edinburgh to Glasgow Relays between 1963 and 1982 including an unbroken streak of fifteen (1963, 64, 65, 66, 67. 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77 + 81, 82) races running six different stages with only the second and third escaping his attentions. Even during his busiest hill running years, he still turned out in the E-G for the club, as well as many races such as County and District Championships.

As a mountaineer

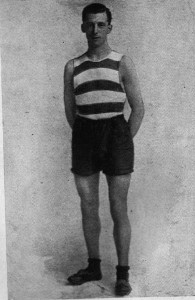

Early on Bobby developed his love for the mountains and was a regular with the club’s hill walking and climbing group with Allan Sharp, David Panton, Pat Younger and Frank Kielty of the old guard plus Jackie Girvan and Hugh Hoole. The picture below shows how young he was when he started, the heights he reached and the rope indicates that it was not the tourist track up either!

They climbed all over Scotland and every one of them had run in the Ben Nevis race as well. On a trip to the Alps in the late 1960’s a group of Pat, Allan, Jackie, Hugh, David Panton and Hugh Hoole were leaving in an old Volkswagen bus with a 1200 cc engine that Pat had got from somewhere when Bobby came running down the street with his bags, got in and made the party up to eight. With their bags, it meant that the VW was carrying about the weight of fourteen or so fully grown men on a 1200 cc engine!

His competitive career went from the mid 1960’s right through to the 1990’s. He was a member of some of the very best club teams winning medals on the track, over the country and on the roads all over Scotland although his great talent was for hill and fell running with many firsts to his credit. As a race organiser he was responsible for many serious endurance challenges and it is good to see the Arrochar Alps restored to its place on the calendar after five years. At club level he was a Committee member for several years and acted as club captain.