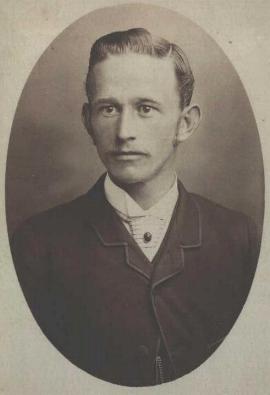

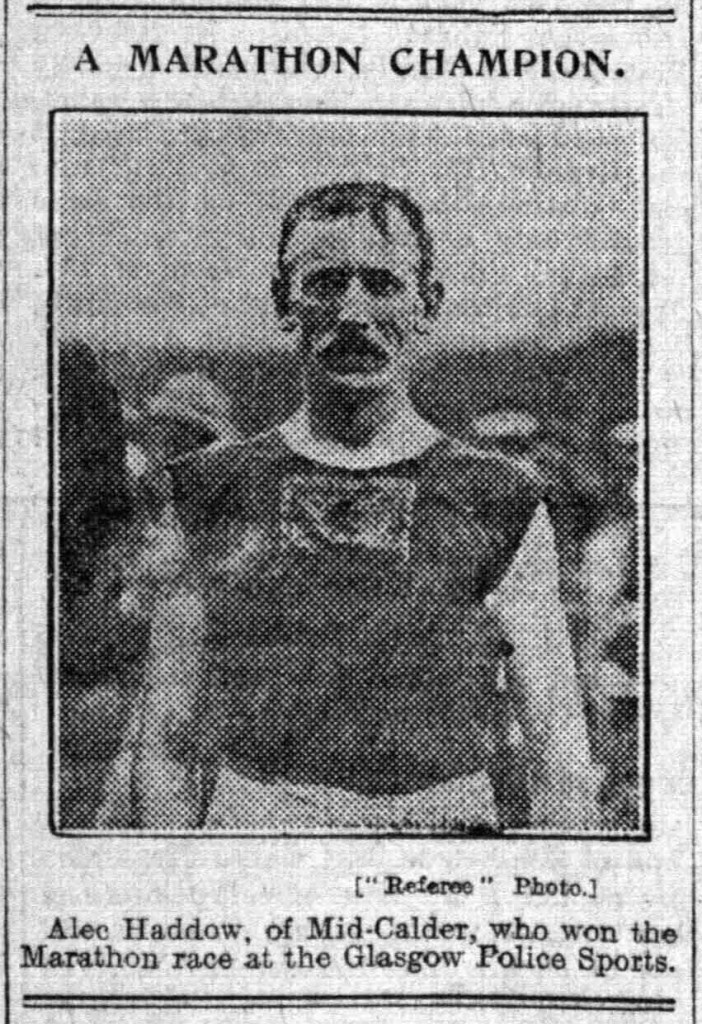

Alexander Williamson Haddow (b. 03.10.1873, Mid-Calder, Midlothian. d. 30.04.1915, Winchburgh, West Lothian)

Few people will have ever heard of “Sandy” Haddow, but for many years he was one of the greatest professional runners in Scotland. An exceptionally popular personality just over a century ago, Haddow lit up the tracks of Scotland with his fearless racing style and performances. Alexander Williamson Haddow was born in the village of Mid-Calder on 3rd October 1873, the son of Elizabeth and Walter Haddow, a shale miner. Haddow, like his father, also became a shale miner. Mining was not a particularly well-paid occupation, but for many in this area it was the only occupation they knew. Haddow was employed by the Oakbank Oil Company Ltd., one of the leading shale oil companies in Scotland. It also provided its workers with everything from cheap housing to iron frames for the beds, not to mention amenities such as an institute, a bowling green and a football pitch. Sport was a very popular leisure activity in the mining villages of West Lothian. This was the Qatar of Alex Haddow’s day. It witnessed the world’s first oil boom after the discovery here of oil-bearing shale in 1850, nearly a decade before the first oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania.

As was typical in those days, Haddow did not take up foot-racing seriously until he was in this early twenties and was identified very early on as having exceptional potential. He made his first major appearance in 1896, and what a debut it was! The event was the Powderhall Mile Handicap on New Year’s Day 1896. Haddow did not feature in the pre-race odds. There were 50 starters, including Craig, the scratch man, and W. Williams, Edinburgh, 15 yards, both of whom retired early in the race. Taking full advantage of a 150 yards’ start, Haddow took the lead on the third lap and won as he liked in 4:14.0. He took home a first prize of £12, not to mention his bookmaker’s winnings. To give an idea of how much money this was, the average coal miner took home about £2 a week at the time.

The aforementioned “Craig” was, incidentally, one of the brightest stars of the Scottish pedestrian scene in those days. His real name was George Blennerhassett Tincler. The son of a Dublin solicitor, he lived in Inverness and belonged to that rare breed of runner with a scratch mark. Then again, Tincler was arguably the number one miler in the world at the time. In 1897 he ran 4:15.2 mile in the USA and unofficially accomplished a staggering 4:08 for the same distance in a time trial.

Haddow’s handicap was slashed after winning at Powderhall, but that did not stop him scoring a sequence of wins that season over two miles at Thornton, Bridge of Allan and Crieff – where the annual Highland Games could draw as many as 50,000 spectators. “Wee Haddow”, as he was called by his fellow “peds”, became a familiar figure at the “gemmes”. Most of his races were handicaps. They were typically untimed and decided on rudimentary grass tracks. One of the few foot-racing venues in Scotland where a bona fide mark could be achieved was Powderhall Grounds in Edinburgh, then under the management of a Mr. W.M. Lapsey, who always ensured that the quarter-mile cinder track was kept in excellent condition. Haddow raced here often, where main fixtures on the annual calendar were the New Year promotion and the Queen’s Birthday meeting in May.

On New Year’s Day 1897, he returned to Powderhall and took the third prize in the mile, finishing 9 yards behind G. Smith, Colinton, who won in 4:22.2 off 130 yards. Haddow’s handicap was now down to 75 yards, bringing him closer to the backmarkers. His time is the equivalent of 4:16.6 for 1500 metres, which is a useful benchmark by which to judge his many handicap performances.

On 20th May, 1898, at the Queen’s Birthday meeting, he was fourth running off 70 yards. No time was given as it was a handicap although the winner was given 4:20.5) . Like many handicaps at that time the field was expected to be big but with an entry of 95 it must have been difficult weaving his way thgrough from the 70 yard handicap. Less than a month later, at the Tranent Fair and Sports on 16th June Haddow showed off his fitness by running second in both the half-mile and mile handicaps, before taking third in the two-mile handicap. In the latter he finished one place behind Stirlingshire veteran Paddy Cannon, holder of the world three and four miles records and still a regular feature on the Highland Games circuit at the age of 41.

The prize money on the games circuit was good and an elite runner could earn quite a bit of money during the summer months, although of course the competition was fierce and the fields big enough to keep even the best foot-racers on their toes.

At the Dunfermline Highland Games on 18th July Haddow came fourth in the mile off 65 yards, once again finishing one place behind Cannon (off 140 yards), although later in the day he gained the first prize in the one-and-a-half mile handicap off 100 yards ahead of J. Darwin (65 yards). Darwin (whose real name was James McDermott) also hailed from Mid-Calder and was one of Haddow’s rivals, a prolific winner of middle-distance races on the games circuit in Scotland and Ireland between about 1892 and 1906. On 31st August 1901 he notably beat the ex-amateur champion James Duffus over a mile at Wishaw in 4:35.0. His life was snuffed out in 1910 when he sustained horrific injuries while trying to board a moving train.

On 20th May, 1899, at Powderhall, running in a handicap mile at the Queen’s Birthday meeting Haddow was first, off 95 yards in 4:14.5 [equivalent to 4:10.8 for 1500m] which was a definite improvement on his previous form.

The P&P report read: “The one-mile event produced a very hot performance from A. Haddow, Mid-Calder, who won that even in 4 min. 16 sec. from 95 yds, giving a glimpse of talent still to be developed among the ranks of the middle-markers.” The time was actually 4:14.5.

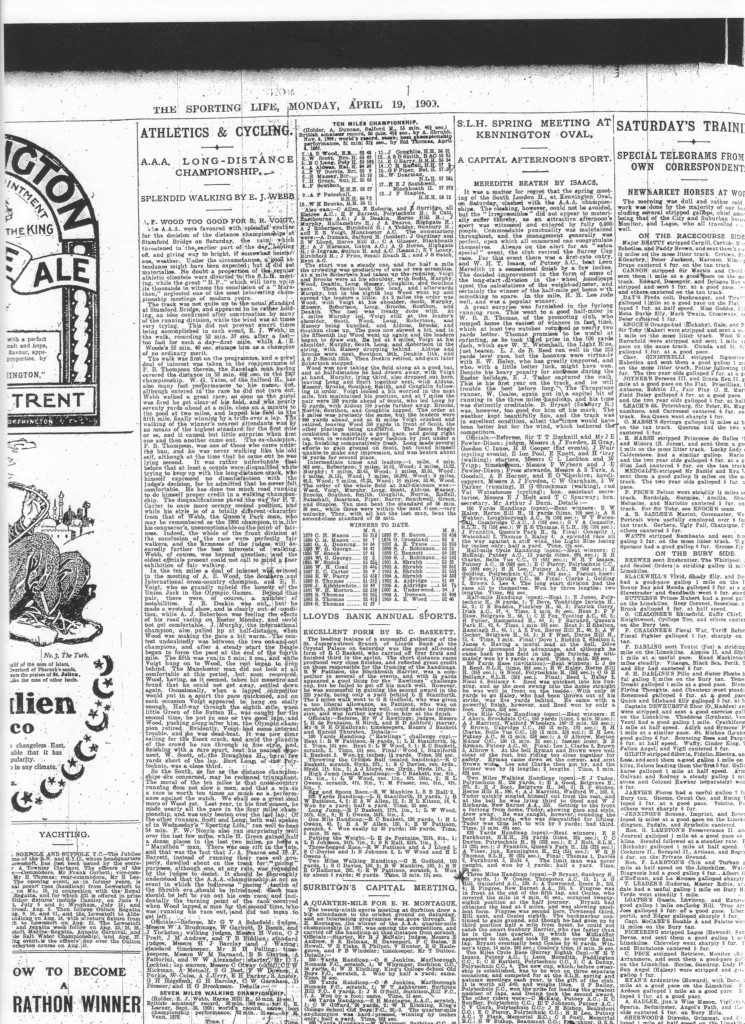

The oldest foot race in the world, the Red Hose Race, is held at Carnwath in Lanarkshire at the end of July each year although in Haddow’s day it was run in mid-August. The race dates from 1508 and is a real classic event. It is run under the jurisdiction of the Crown Authorities whose permission must be obtained before any alterations are made to the race. Alex Haddow won the race twice – in 1899 and in 1901. This would be impossible now since rules were changed in 1966 that restricted contestants to those living in eight local communities. On 16th September 1899 Haddow was one of the pacemarkers who helped pace Harry Watkins to a professional one-hour world record of 11 miles 1286 yards at Rochdale. Although Watkins was successful in the attempt, the Press at the time was a tad less optimistic. The tale of the race build up is encapsulated here.

“When FE Bacon made his successful attempt on Deerfoot’s hour record in June, 1897, he was most admirably paced by Harry Watkins, the old Southern cross-country champion, who led Bacon for nearly two-thirds of the long journey. This wonderful performance by Bacon on that occasion naturally attracted attention to Watkins’s fine running, and the latter has since justified the high opinion then formed of his capabilities by beating Leonard Hurst at ten miles for £100; GB Tincler, the world professional champion for two miles, for the same stakes; and later Bacon at ten miles for the championship and £200. Ever since the last-named race was decided in April last, Watkins has been anxious to have an opportunity afforded him of setting up fresh figures for an hour’s run and, failing to obtain an offer of a prize, he has decided to make the attempt on the Rochdale track this afternoon for the gate money alone. Bacon had a much greater incentive to success as he was guaranteed £250 plus half the gate receipts if he beat record. Watkins has been in strict training at Blackpool for several weeks and is very fit and confident.

He will be paced by Hurst, Haddow and Walsh on foot, and H Brown, the well-known racing cyclist, will accompany him on a bicycle. Of course, much will depend on the weather, the pace-making and the state of the track, but given the most favourable conditions, it is doubtful whether Watkins will succeed so difficult is his self imposed task. With the exception of Hutchens’s 300 yards in 30 seconds, and WG George’s mile in 4 mins 12 3-4th secs, there is probably no running record to beat as Bacon’s 11 miles 1,243 yards in 60 minutes, and Watkins is a greater runner than his most ardent admirers consider him to be if he succeeds in wiping it out.” He did get the record – albeit by only 43 more yards but the assistance given by the three runners and the cyclist (I’m doubtful about the aid of a cyclist in record attempts but it didn’t affect the runners or officials on the day or afterwards.)

On New Year’s Day 1900 Haddow finished third in the Powderhall Mile Handicap off 55 yards, covering 1690 yards in 4.12.5, a time equivalent to 4.05.1 for 1500 metres. This was superior to the officially recognised world-leading time that year of 4:06.2 by Charles Bennett. The full result: Powderhall, Mile handicap, 1st January, 1900: 1, E. Fleming (Uphall, 175y) 4:11.2; 2, A. Shanks (Airdrie, 150y) 10y; 3 Alec Haddow (Mid-Calder, 55y).

In 1901 Haddow, at Keswick on 5 August, ran a 4:24.0 mile off 15 yards, the conversion having been done as it always had to be with handicaps,this being equivalent to 4:08.2 for 1500m. Only nineteen days later he posted a world-leading 2 mile time of 9:39.2 in Glasgow.

There were many gaps in results available for Wee Haddow and we have to jump almost a year before the next appearance. He must have been racing and training well for in 1903 Haddow scored double victories over former mile and hour record holder Fred Bacon. The first was in an international 4 mile race at the Cupar Highland Games on 27th June, which was billed as ‘The Greatest Footrace ever held in Scotland’ . Competing for prizes of £5, £3, £2 and £1 were

*Harry Watkins, England, Champion of the World 4 to 15 Miles

*RF Hallen, America, holder of World’s Record 21 to 25 miles

*JJ Mullen, Champion of Ireland

*FE Bacon, England, 1 to 10 Miles Champion

*Alex Haddow, Champion of Scotland

*Len Hurst, England, 15 to 20 Miles Champion

*J Collins, Champion of Essex, and

*R Young, Mid-Calder.

Haddow won in 21.04.5 so there had to be a rematch. This was for the “Four Miles Championship of the World” and was held at Powderhall on 25th July the same year, and again Haddow was the victor, this time in 21.01.2. In both races a soggy track prevented faster times.

He disappeared at this point for five years and Alex Wilson comments that he had a few fallow years, before rediscovering his form in late 1908. 1910 was his last competitive year (he was 37 then) and Wilson reckons it was his best.

When marathon running became popular after the Olympics in 1908, Haddow turned to the longer distances and proved that, even at 35, there was still plenty of life left in his legs. On November 21, 1908 Haddow defeated John McCulloch (Strathmiglo) in a “marathon” race from Glenfarg to Cowdenbeath, the first of its kind in Fife, for a stake of £50. He won by over quarter a mile, covering the 15 mile course in 1:24:13. “Great importance was manifested in the race along the route,” wrote the Dundee Courier, “and an estimated 4000 spectators lined the street at Cowdenbeath.” The actual race report read:

“FIFE MARATHON RACE

HADDOW OF MID-CALDER DEFEATS THE STRATHMIGLO CRACK IN FIFTEEN MILES CONTEST

A Marathon race for a stake of £50 was run on the Great North Road between Glenfarg and Cowdenbeath, a distance of fifteen miles, on Saturday afternoon. The competitors were those well-known runners, John McCulloch (Strathmiglo) the winner of the Dalkeith to Edinburgh race, and Alex Haddow (Mid-Calder).

The men ran together for one mile. Then Haddow gradually bore ahead and by the time Milnathort was reached the distance between them was 400 yards. Haddow improved his position and finished with a lead of 700 yards. The time taken was:- Haddow 1 hour 24 minutes 13 seconds; McCulloch 1 hour 26.5 minutes. Great interest was manifested in the race along the route and at Cowdenbeath there would be over 4000 people lining the street.”

It is an interesting comment at the end of the article – a race between two men over 15 miles and interest was such among the population that Cowdenbeath could provide 4000 spectators. In the twenty first century in what is said to be a sport loving nation, there are years when there are fewer than that at our national championships.

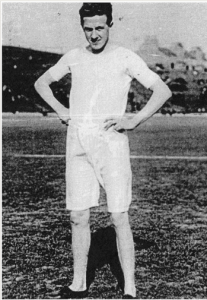

The 1909 Powderhall Marathon start: 17 is Frank Clark, and the man in black beside him may well be Haddow

His road running career had started with a victory and that led into two very good years for him on the roads. They started on the very first day of 1909 in the Powderhall Marathon which was the first run over the full marathon distance of 26 miles 385 yards and went from Falkirk to Powderhall. He set a very fast pace, leading the race until 16 miles before blowing up in the thick mud on the course.

The race started from the Victoria Public Park in Falkirk and finished in the Powderhall grounds. Prizes totalled £100 and the possession of a silver cup for one year. Right up to the last minute it looked as though the weather would have made the race very difficult but the weather cleared up enabling the race to be run in reasonable conditions but the underfoot conditions had been severely affected and they made it hard for the runners. The runners gathered in the Victoria Public Halls where they were examined by a doctor who pronounced them all fit and in good condition. They were also provided with stimulants and food, and then 54 men faced the starter. Provost Christie of Falkirk was the starter but after the men had lined up on the track in the park, he took time to address the runners and the large crowd that had turned up before raising the flag to start the event. Haddow led the way until half a mile past Kirkliston when he dropped out complaining of pains in his ankles and his thighs. H Saint Yves of London was the man who took the lead, plodded on gamely and eventually won in 2:44:47, T White of Dublin was second in 2:47:55 and P Hynes, also from Ireland was third in 2:50:55. Saint Yves was a 20 year old Frenchman from Paris who had come to London to run in the professional marathon there but was to late to enter. The times seem very good bearing in mind the distance and the conditions but it was not a good day for Haddow.

Also running in the race as a professional from Glencraig in Fife was Frank Clark who had been encouraged by Haddow, living in Lochore, to take up the marathon: a wise decision as Clark set a Scottish record of 2:40:54 a year later.

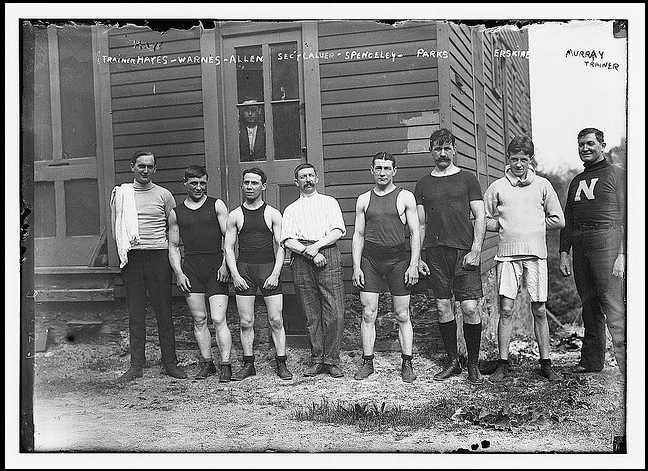

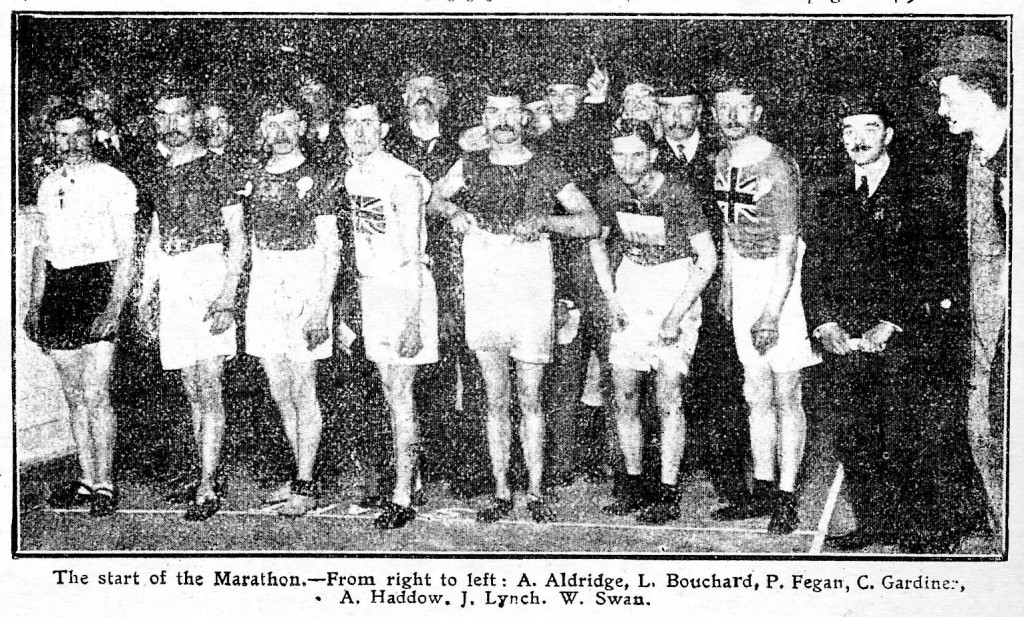

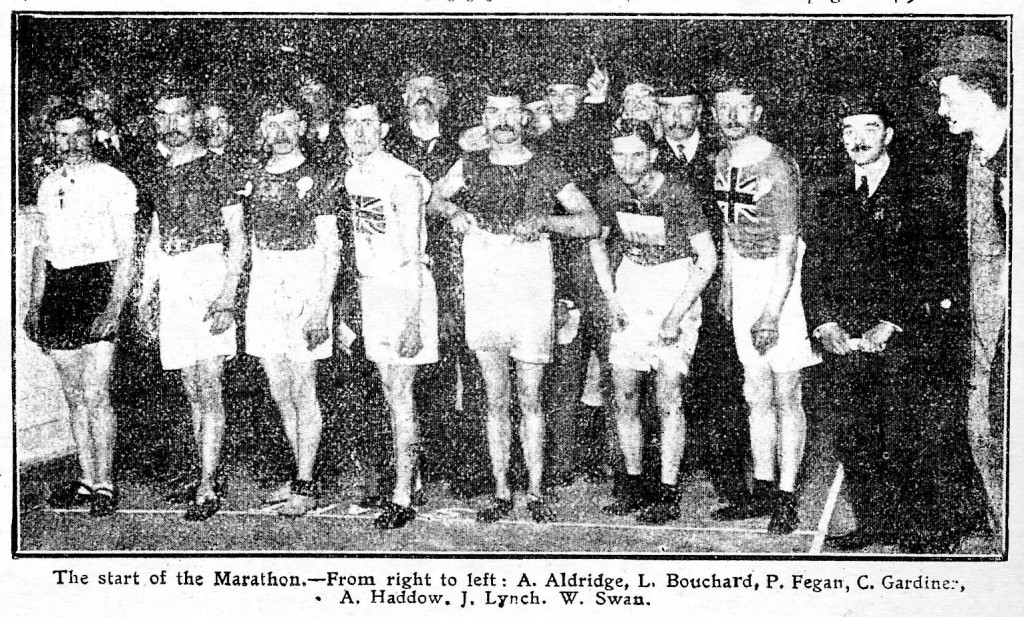

The illustration above is of the start of the 1910 Agricultural Hall Marathon. Held on 26th March, 1910, it as the first of a series of marathons organised by the United Sports Syndicate, which would lead to the presentation of a grand challenge belt – a deliberate return to those presented in the past to some of the great champions. The competitors were A Aldridge (England), L Bouchard (France), W Swan (Wales), P Fegan (Ireland), L Lynch (Ireland), A Haddow (Scotland) and CW Gardiner. The public was assured that ‘each man was thoroughly trained and possessed the credentials to compete in any championship. The Agricultural Hall had long been used for professional meetings and this marathon was an indoor event. After a ‘flashlight photograph’ had been taken for the Press – see above – the race got off to a fair start. Haddow went straight into the lead and covered the first mile in 5:08 and got to two miles in 10:27, already lapping Lynch. Fegan was second, followed by Gardiner and Bouchard. Haddow ‘making the pace too warm to last’ came through three miles in 15:53.4 and five miles in 26:45 ‘Haddow, who has been doing a lot of short distance running lately, ran as if to finish at ten miles.’ At 10 miles in 54:17 the Frenchman Bouchard was looking like the winner but Haddow was still in front with Gardiner third and Aldridge, Fegan and Swan all running well. Haddow was still in the lead at eleven miles in 60:03.4 but another half mile on ‘Haddow was now paying the penalty of his rash pace at the start and was forced to retire with stomach trouble.’ He stepped off the track but returned and was running in third for a while but he wasn’t the only one having trouble and Gardiner had his legs rubbed with whisky to help him on his way – to no avail however as he, Haddow and Lynch all retired from the race won by Bouchard in 2:36:18 from Aldridge in 2:48:58 and Swan in 2:53:10 with Fegan the last to finish in 2:58:33.

Bouchard’s splits were given as 1:06:8 for 12 miles, 1:11:52 for 13, 1:17:53 for 14, 1:23:36 for 15, 1:29:22 for 16, 1:35:23 for 17, 1:41:34 for 18, 1:47:53 for 19, 1:54:13 for 20 miles, 2:00:35.4 for 21, 2:07:14.4 for 22, 2:14:15.4 for 23, 2:21:05.4 for 24, 2:28:17.4 for 25 and 2:35:01 for 26 miles. It was pointed out that, if the times were correct, all the times from 20 miles were world records.

Although many long distance races were held indoors – just look at the career of Arthur Newton for example – with the six day and 24 hour races being quite popular, it does seem strange in the twenty first century to have an indoor marathon. Newton complained at times of the nature of indoor tracks and on several occasions asked for square tracks for his races. In the circumstances, the winning time of 2:36:18 was actually very good.

Haddow wasn’t finished with long distance running though and just three months later, on June 20, 1910, he defeated Gardiner and Hefferon to win a 15 miles championship at Ibrox Park in 1.24.17.6, a time slightly slower than Bouchard recorded for the same distance en route to the marathon victory in March. The report in the ‘Aberdeen Daily Journal’ for Wednesday June 22nd read as follows:

“A 15 mile championship race for £150 between G Gardiner, England, FC Hefferson, champion of South Africa and Alex Haddow, Mid-Calder, was decided on Monday at Ibrox Park, Glasgow, The weather was fine, but a fair breeze was against any of the competitors coming near record time, the wind strengthening as the race proceeded. The three men got away to a fine start, and for the first two miles kept well together, Haddow and Gardiner taking the lead alternately. After four miles Hefferon started to fall behind, being half a lap in the rear at the end of the sixth mile, lapped at seven and a quarter miles and at nine and a half miles the South African had to give up. Gardiner and Haddow continued to run off the miles at a fair even pace, there never being more than a yard between them. Entering on the last mile Haddow forced the pace and led by 20 yards. This he maintained to then last lap when Gardiner put on a fine spurt and reduced the Scotsman’s lead to five yards. In the straight the Englishman made another great effort to get ahead, but the Scotsman was equal to the call, and in a magnificent finish Haddow won by a foot. Gardiner’s splendid spurt in the last lap to catch the Scotsman roused the crowd to a high pitch of enthusiasm, and before the men had reached the tape, they swarmed the field, cheering both men enthusiastically. Haddow’s time for the full distance was 1 hour, 24 minutes 17 3-5th seconds of which he covered ten and three quarter miles in the hour.”

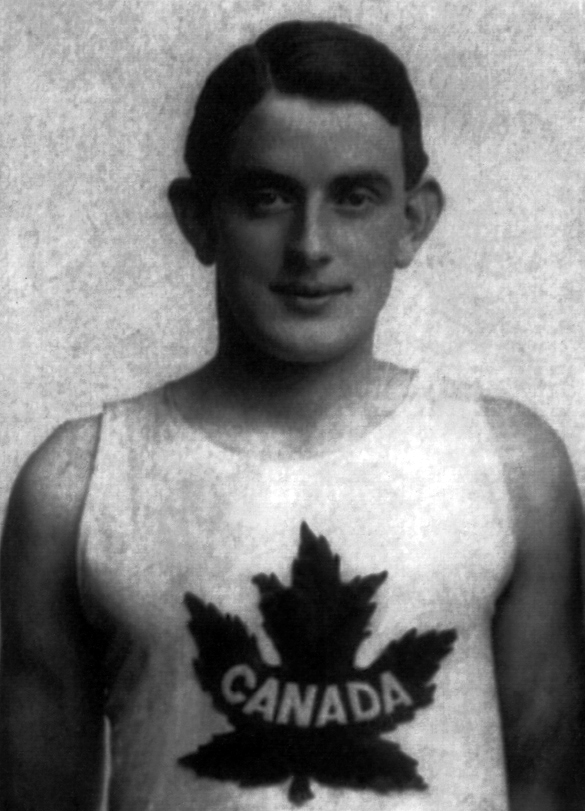

Haddow with the 15 miles trophy

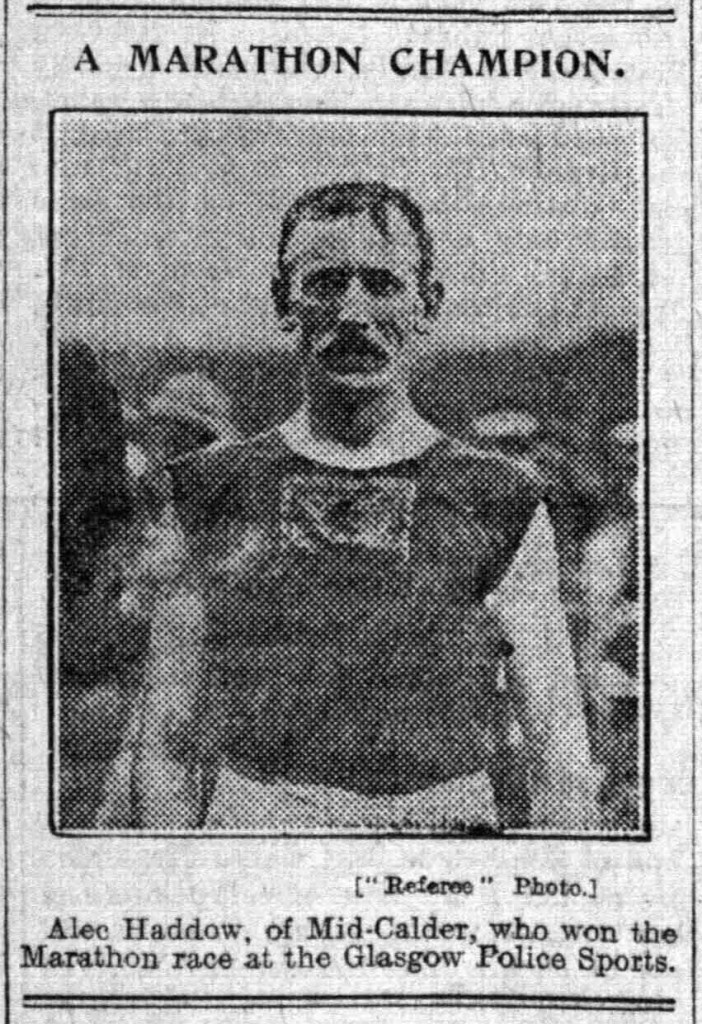

Five days later, at the Glasgow Police Sports, he trounced a veritable “who’s who” of professional distance running to win a world championship 12 mile race in 1.04.52.8. It was a Scottish record, as was his distance at one hour of 11 miles 200 yards. ‘Lloyd’s Weekly News’ reported on the race:

“PEDESTRIANISM

Gardiner Beaten In Glasgow

At Celtic Park, Glasgow, yesterday, the principal event in the Police Sports was a 12 miles level running race. Result: A Haddow (Mid-Calder) first; P Fegan (Dublin) second; CW Gardiner (Lewisham) third; Louis Bouchard (Paris) fourth; C Dinning (Cashel) fifth; J Price (Birmingham) sixth. Gardiner led at the end of the first mile in 5 min, but then fell back, the leaders being alternately Bouchard, Haddow and Fegan. At 5 miles in 26 min 40 sec, Bouchard began to fall away. Haddow drew ahead and covered ten miles in 53 min 45 sec, a furlong ahead of Fegan , and he eventually won by 350 yards in 64 min 52 sec. Gardiner beat Bouchard for third place by a foot.”

The ‘Scottish Referee’ said afterwards that ‘Haddow’s win in the fifteen miles at Ibrox Park’ , coupled with his performance on Saturday, stamps him as one of the best distance runners in or out of Britain, and this after so many years on the track.’

A few weeks later, on July 11, 1910 Haddow again beat off Charlie Gardiner in an hour race at North End Park, Cowdenbeath, winning by a quarter of a mile with a distanceof 10 ¾ miles. Thereafter he continued to compete in 1911 and 1912 but the races seemed to be few and far between.

It had been a very interesting career – starting out running the Mile and Two Miles, racing against some of the ‘greats’ such as Tincler – a name known to few now but a very good athlete indeed and one worth researching by any student of endurance running – and concluding with long distance racing on the road, on the track and even indoors on the track. After he retired from professional running, he was working as a fireman at the Duddingston Mine in Winchburgh. It was shale mining and not an easy option for anyone: if you want to know more about it then the website http://www.scottishshale.co.uk/index.html has a history of shale mining in West Lothian.

Then in May 1915, the newspapers carried reports such as this one from the ‘Surrey Mirror and County Post’.

“Alex Haddow, 41, of Winchburgh, who for many years as one of the greatest of professional runners in Scotland from half-a-mile upwards, died in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary from injuries received in a burning accident sustained while at work as a mine foreman.”

Such a gas explosion was an occupational hazard in shale mining. He was aged only forty-one.

Alec Haddow’s best track performances:

| 1500m |

4.05.1 [extrapolated] |

Powderhall (hcp) |

January 1, 1900 |

| 2 miles |

9:39.2 |

Glasgow |

August 24, 1901 |

| 3 miles |

15:30.2+ |

Powderhall |

July 25, 1903 |

| 4 miles |

21.01.2 |

Powderhall |

July 25, 1903 |

| 6 miles |

32.10i+ |

Islington |

March 19, 1910 |

| 10 miles |

53.45+ |

Glasgow |

June 25, 1910 |

| 11 miles |

59.22+ |

Glasgow |

June 25, 1910 |

| 1 hour |

11M 200y |

Glasgow |

June 25, 1910 |

| 12 miles |

1.04.52.8 |

Glasgow |

June 25, 1910 |

| 15 miles |

1.24.17.6 |

Glasgow |

June 20, 1910 |

Alex Wilson’s work on the above profile must be acknowledged here – the original framework, both photographs and additional information was willingly given and gratefully received. He has also passed on a comprehensive list of Haddow’s marathons between 1908 and 1911 which is below

| 21.11.1908 |

Fife Marathon (15 miles) |

1 |

1.24.13 |

| 01.01.1909 |

Powderhall Marathon (26 miles 385 yards) |

DNF (retd. 16 miles) |

1 – Henri St. Yves (France) 2.44.40 |

| 05.04.1909 |

Methil Marathon (12 miles) |

2 (1:14.09.5) |

1 – Frank Clark (Lochgelly) by half a yard in 1.14.09.4 |

| 05.06.1909 |

Cowdenbeath, Marathon (9 miles) |

2 |

1 – Davie Butchart (Kirkcaldy) |

| 19.06.1909 |

Glasgow Police Marathon, Celtic Park (20 miles) |

DNF |

1 – Charlie Gardiner (Lewisham) 1.58.03.8 |

| 26.06.1909 |

Blairadam Marathon (10 miles) |

2 |

1 – Frank Clark (Lochgelly) |

| 17.07.1909 |

Strathaven Marathon (18 miles) |

2 in 1:57.30 (£5) |

1 – Frank Clark (Lochgelly) 1.57.00 |

| 26.07.1909 |

Marathon (Lochgelly-Kinross) (10 miles) |

2 |

1 – Davie Butchart (Kirkcaldy) |

| 01.08.1909 |

Greenlaw Marathon (5 miles) |

2 |

1 – Archie Revel (Falkirk) |

| 25.08.1909 |

Birnham Marathon (Perth-Birnam) (14 miles) |

3 in 1:21 (£1) |

1 – Charlie Gardiner (Lewisham) 1.21.00 |

| 03.01.1910 |

Powderhall Marathon (26 miles 385 yards) |

DNF |

1 – Jack Price (Halesowen) 2.40.07.5 |

| 19.03.1910 |

Agricultural Hall Marathon (26 miles 385 yards) |

DNF (retd. 12 miles) having led at 11 miles in 1.00.03.4 |

1 – Louis Bouchard (France) 2.36.18 (world record) |

| 07.06.1910 |

Lumphinans Marathon (10 miles ) |

1 |

|

| 20.06.1910 |

15 mile championship, Ibrox Park |

1 |

1.24.17.6 (Scottish record) |

| 25.06.1910 |

Glasgow Police Marathon, Celtic Park, 12 miles |

1 (won by 350 yards) |

1.04.52.8 (10 miles 53:45.0) |

| 11.07.1910 |

Cowdenbeath, North End Park (1 hour match against Charlie Gardiner) |

1 |

10 ¾ miles (47 laps 25 yards); won by half a lap |

| 02.10.1910 |

Coldstream Marathon (6 miles) |

1= |

Tied with Frank Clark |

| 20.07.1911 |

Methil Marathon (10 miles) |

2 (£2) |

1 – D. McKeever (Airdrie) |

Lanark Racecourse where the first cross-country championship was held. Racing was conducted here until 1977 and for several years the course was walkable: it is now country park.

Lanark Racecourse where the first cross-country championship was held. Racing was conducted here until 1977 and for several years the course was walkable: it is now country park.