Jay Scott would have been a wonderful athlete in any generation – his performances over a number of years speak for themselves. He would have been much better known however had henot been competing as a professional athlete at a time when the amateur code held sway and there was little coverage in any of the media. His marks, good as they were, would have been even better had he been able to compete on the same surfaces and had the same competition opportunities as the amateur athletes of his day.

Born in Ayrshire, Mr Scott’s family moved to farm on Inchmurrin island, Loch Lomond, when he was two years old. Rowing to school across the water every day with his older brother Tom, Jay soon became skilled in boatmanship and acquired a considerable knowledge of the loch, later coming to the rescue of many a stricken tourist. After boarding school, he attended the West of Scotland Agricultural College before returning to farm on Inchmurrin. Despite claiming to be one of the smallest children at school, he soon built up an athletic physique and began to excel in Highland Games competitions.

He began entering highland games events in the 1950s and, on his day, was well nigh unbeatable. At Tobermory Games, for instance, he once won the 100 yards, 220 yards, hop, step and jump, long jump, pole vault, seven heavyweight events, and also the high jump, beating an American Olympic athlete into second place with a leap of 6ft 3ins. At the Aboyne Games, he won the trophy for best athlete seven times in a row, and, in a match against the leading decathlete of the day, was so far ahead after eight events that there was no need to throw the discus or run the 1,500 metres. There is also the story of how, arriving at the Taynuilt Games too late for the high jump, he then beat the winner’s height clad in his kilt, coat and street shoes. Such was his prowess that versions of this story that have him clearing the bar carrying two suitcases are regularly believed and recycled. There are many such stories – for example, at the Luss Games in 1954 he was said to have jogged through the blistering heat from one event to the next, and won almost every local event and most of the open field games.

If we take some actual examples,

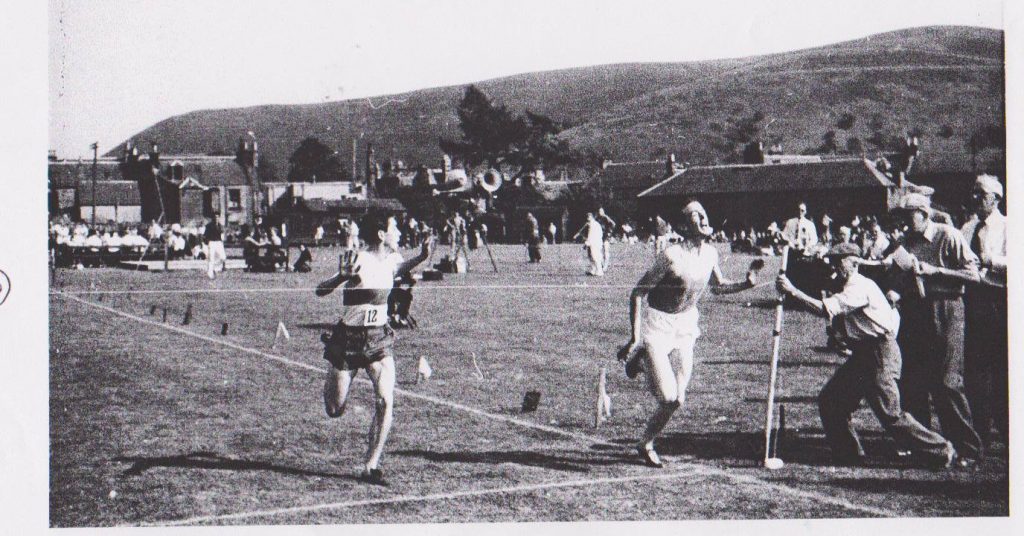

* at Dingwall on the last Saturday in July, 1955, he won eight events and the report in the ‘Glasgow Herald’ read: “Three of the chief trophies in the open events at the Dingwall Highland Gathering on Saturday were won by J Scott (Inchmurrin), who also broke two of his own ground records. In the high jump he cleared 5′ 10″ – 1″ more than the previous record – and in the hop. step and jump he leapt 43′ 01″ – 3″ better than his previous best. Altogether Scott was first in eight events. For scoring most points he was awarded the challenge rose bowl, and he received the Fraser Challenge Cup for the open jumps, and the Macrae Challenge Plate for the 100 yards.”

How does the hop, step and jump compare with his amateur contemporaries? Well his 43’01” = 13.132m; the SAAA Champion that year cleared 13.94m which is 45’3.5″. Bearing in mind the other seven events tackled by Scott, and the difference in competition surfaces, and the level of competition, I would suggest that it stands up very well indeed. Incidentally, the SAAA victor was Tom MacNab.

* The following week, he only won the high jump while his brother Tom won the long jump and the pole vault.

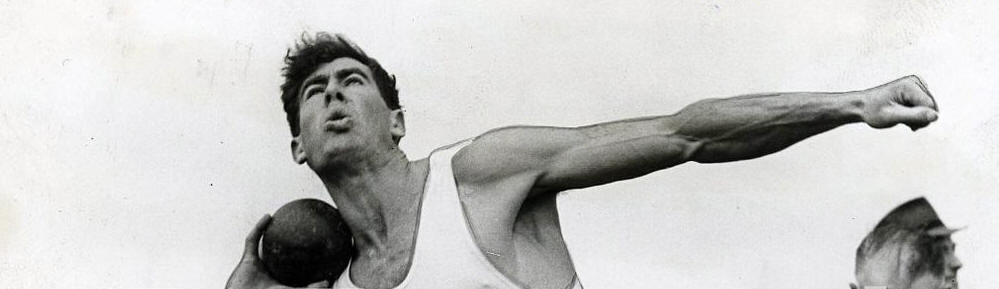

*On the 13th August, it was the Taynuilt Games where he turned his attention to the heavy events beating Ewan Cameron in the shot with 40′ 10″ and the long jump with 20′ 8″. The SAAA Shot was won by TA Logan with 13′ 46″ (Jay’s converted to 12.446m) but the previous provisos still maintain. This was only one year after he started competing and he and his brother Tom won a staggering range of events: 100 yards, shot putt, high jump, long jump, hop, step and leap, and pole vault among them. To achieve such success, they must have trained very hard or been really blessed with great natural ability.

Probably both is nearer the truth but we are still left with the question about what they could have done with big city facilities and opportunities. In 1964 for instance Jay high jumped 6′ 3 1/2″ at Tobermory – the SAAA champion then was the wonderful Crawford Fairbrother who had a season’s best of 2.05 metres. Jay’s high jump would convert to 1.91m which would have placed him fourth home Scot in the rankings that year – second being Alex Kilpatrick an Anglo living in London (1.98m), and third Patrick MacKenzie, another Anglo living in Brighton. (1.97m). The next home Scots were David Cairns of Springburn and Alan Houston (VPAAC) on 1.94m. It was during the late 50’s when his portrait started to appear on the Scott’s Porage Oats packets and the question was – was he paid? His son Rob is quoted in the ‘Edinburgh Evening News’ as saying the first he knew of it was when a friend spotted him on the packet. He then his son reckons got a one off payment when he approached the company. It would have been vastly different in the twenty first century!

His fame spread, and he was invited to go on a world tour. He tossed the caber in the Bahamas and, in 1964, visited Canada and the US. The stories just kept coming: this from The Scotsman “Here his beguiling form came to the attention of film star Jayne Mansfield, always on the lookout for someone whose physique matched her own extraordinary proportions – she was eventually to marry body-builder Mickey Hargitay – who invited him to spend the night on her heart shaped bed. They were, however, not alone in Ms Mansfield’s pink boudoir. Also there were her lapdogs. Scott was so bothered by them yapping at his heels that he asked for them to be taken away. He might as well have requested that she remove her make-up. Minders were summoned, and the man who had beaten all-comers on the games field was unceremoniously dumped into her swimming pool.” That’s the story anyway.

At Aboyne, 1955

His athletic stature really caught the eye of his future wife Fay when they met in June 1957 at Loch Lomond. Fay was starring in a show at the Alhambra in Glasgow when they started dating. They wed the next year at Kilmaronock Church, near Drymen. They lived on Inchmurrin for six years as Mr Scott continued to collect trophy after trophy at Highland Games competitions. The Scotts moved to a house on the shore of Loch Lomond in 1964 and began work on what is now Duck Bay Marina. Scott won a Civic Trust award for his work on the complex, but tragedy struck soon afterwards when the family home was burned down in a fire. The family moved on a few years later to a farm near Aberfoyle, but soon afterwards, in 1973, Mr Scott suffered a serious head injury in a tractor accident. He no longer took part in as many competitions, but the accident, and a subsequent brain operation, left him in poor health and his glory days as one of the country’s top athletes were over, although he still holds a Highland Games high-jump record. The family moved to Edinburgh where they took over a guest house in Portobello. They later gave up the business and Mrs Scott taught drama at Queen Margaret College. Recently, in May 1997, Mr Scott had been focusing on the refurbishment of a 40-foot boat on Loch Lomond. However, he suffered a major set-back when the vessel was vandalised, and, after a minor stroke, he was seriously ill in the last six months of his life, and succumbed to a heart attack two days before his 67th birthday.

There is an excellent obituary in the Glasgow Herald of 9th June 1997 from which much of this has been gleaned and which can be found in its entirety at

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12320487.highland-games-star-jay-scott-dies-after-long-illness/

His career is summarised in the International Highland Games Federation website as follows:

Jay was the youngest of the two Scott brothers who grew up on Inchmurrin,a lovely island on Loch Lomond. The brothers were born in Ayrshire in 1926 and 1930 respectively, and in their boyhood,when attending Kiel School at Dumbarton , they showed little sign of the athletic greatness they were later to display. Both were quite small and although they played rugby they were not outstanding. Working on the island ,however agreed with them and they grew into powerful men,rugged and tanned,wearing shorts or kilts all year round regardless of the weather. Heavy farm work , building , cutting trees and rowing on the loch built tough strong muscles and soon Tom was topping 6 feet 2 ½ inches and young Jay was not far behind him. At 14 stone neither carried an ounce of superfluous weight and tailors found it difficult to belive their tapes when they registered a chest measurement of 44 inches and a waist about a dozen inches less. Tom and Jay began their professional careers at Luss Highland Games – Tom in 1947 and Jay a year later.At first the light events were favoured, but later both joined the heavies and competed with success.

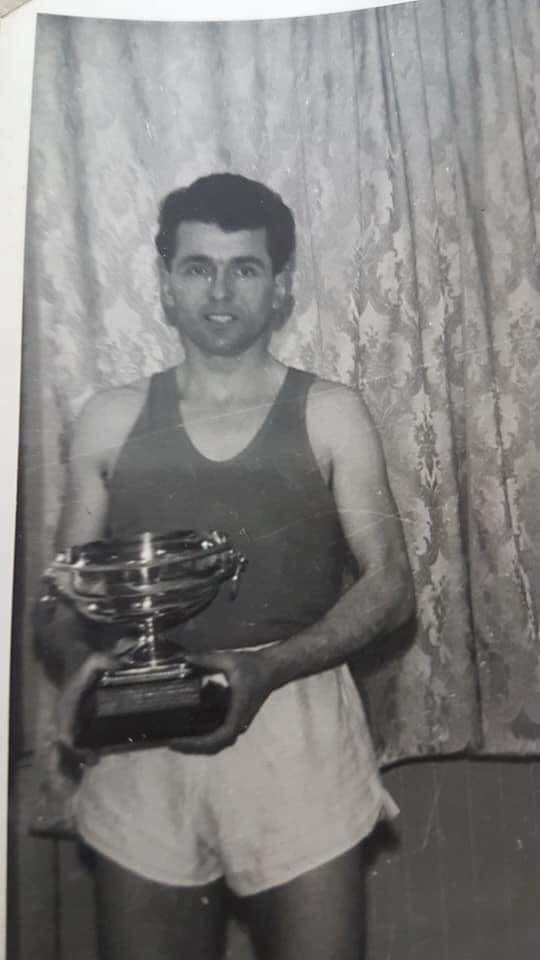

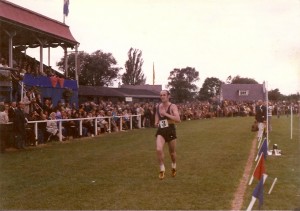

“Jack of all trades, master of none” certainly does not apply to either of the Scotts. Both broke records at more than one event it is safe to say that Jay was the best all round heavy and light event athlete of his era. His performance could hardly be equalled by any one person competing under the conditions prevailing at the games, where all events are run within record. Nobody , to my knowledge, has ever exceeded his record of 51 feet 11 inches at the hop, hop and jump his 48 feet 10 inches in the more accepted hop, step and jump is also a fine effort. The hundred yards done in 9-8 seconds on undulating ground also takes a bit of beating. He came third in the famous Powderhall Sprint, a handicap race,and was back marker in the finals on another occasion. He pole-vaulted 11 feet 5 inches at many gatherings, threw the 56ib weight 34 feet, tossed it over a bar at 14 feet 1 inch, slung the 28 ib weight a full 73 feet at Pitlochry and putt the shot at 47 feet 3 inches. With the stone his distance is 44 feet 5 inches. In 1957 he began hammer throwing and caber tossing at the games and within one season did 110 feet with the hammer and won several prizes on the caber.

Although the island of Inchmurrin is small and quiet, adventure is not lacking. It is such a well -known beauty spot that hundreds of holidaymakers pass the island in cabin launches, canoes, rowing boats and sometimes small dinghies. Loch Lomond can be quite treacherous and more than a score of these holidaymakers have been rescued from drowning by the speedy action and pluck of the two brothers. In addition they have rescued many more who have been marooned in boats or on adjacent islands-quite a serious predicament in a loch 21 miles long. Jay was at the top for several years but actually only won the Scottish Championship once. This was in 1958.

There is a very short clip of Jay and Fay being interviewed in 1957 about their plans for Duck Bay at http://ssa.nls.uk/film/T1732

Quite an athlete, but we’ll never know just how good.