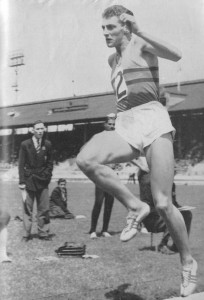

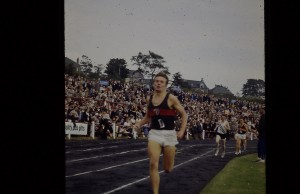

Hamish, on right of GB University team, en route to Turin for World Cross-Country Championship

Hamish, on right of GB University team, en route to Turin for World Cross-Country Championship

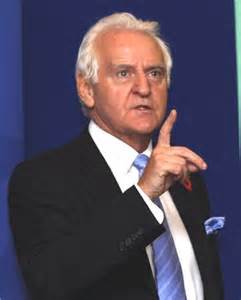

Scotland has produced many very gifted coaches in recent years and the names of John Anderson, Frank Dick, Tom McNab and Tommy Boyle are exceptionally well known. Hamish Telfer – Dr Hamish Telfer – is another very good and successful coach from north of the border and is well respected by his peers but is not all that well known in Scotland itself. Like the others mentioned, he is well educated and is at home discussing the intricacies of coaching theory, like the others he is totally dedicated to sport and has spent countless hours working with athletes of all standards, like them he has worked extensively in the field of sports education and his expertise has helped performers in a wide range of sports. These are all reasons why we should know a bit more about him.

Hamish Telfer was born on the south side of Glasgow in 1950 and brought up in Glasgow where he was educated first of all at Carolside Primary School, and then at Queens Park Senior Secondary School – another similarity because John Anderson had also been a pupil there. He lived in the Clarkston, Whitecraigs and Giffnock areas until 1961. Like all boys in Glasgow he played mainly football, indeed for a short time he was attached to Queens Park Football Club where was a ball boy for the club and for the SFA. But he was also interested in and involved in athletics, after a friend invited him to go along to the West of Scotland Harriers club. He met Cameron McNeish, better known now as a noted outdoors man, hill walker and climber and they were coached by John Anderson. Hamish says that Cameron was picked up by John who realised that they were a good team and therefore included Hamish in the group. They trained hard from about the ages of 15/17 and he remembers a particular session in a snowstorm with Hugh Baillie, Dunky Middleton, Hugh Barrow and Bob Lawrie among others. Both boys started ‘serious’ training about 16 with weights sessions at Springburn Sports Centre, Sunday Grangemouth sessions and training after school. While he did have a life outside of the sport, it was more about training and competing all over Scotland. Did the usual Highland Games circuit of youth handicap races in addition to local and national championships and also went around the country with John as his ‘demonstrators’ for coaching courses

Cameron explains the beginnings:

“I first met Hamish when we both joined the West of Scotland Harriers circa 1964/65. The club was looked after by a lovely old gent by the name of Johnny Todd who took Hamish and I under his wing.

West of Scotland Harriers was predominantly a cross country running club and although Hamish and I considered ourselves sprinters we were encouraged to become involved in everything that was going on at the club, no bad thing for youngsters. That included winter Saturdays at the Stannalane running track near the Rouken Glen where we went cross country running with some fine old timers whose names I’ve forgotten (Hamish will remember). Included in our group was another young athlete who went on to become a Scottish international 400 metre runner by the name of Ian Walker. Ian is now a fairly well known and established folk singer, and we all still keep in touch.

Hamish and I have very fond memories of dank, wintry Saturday afternoons at Stannalane. We probably ran between 5 and 10 miles, mostly around the Barrhead waterworks, and on our return to the ‘pavilion’ – a basic wooden shack, we all had to share one shower to scrape all the cow shit off us! That was followed by a cup of tea and a tea biscuit for which we all donated, if I remember correctly, tuppence!

It was all very Alf Tupper’ish and we absolutely loved it. At that time Hamish showed some promise as a cross country runner and he and I used to finish reasonably highly in Under-15 cross country events, although the lads of Shettleston and Springburn Harriers usually dominated …. “

“We used to go for long runs together as lads. Although I was specifically training as a long jumper Hamish was always happy to do some sprints training with me and I was always willing to go for some long runs with him. We both simply loved athletics and we both loved training, even before we met John Anderson. We did a lot of sprints training on the grass in Queen’s Park, near to Hamish’s parents home in Langside.

As a long jumper Hamish was always happy to do some sprints training with me and I was always willing to go for some long runs with him. We both simply loved athletics and we both loved training, even before we met John Anderson. We did a lot of sprints training on the grass in Queen’s Park, near to Hamish’s parents home in Langside …. “

“We met John Anderson at a schoolboys Easter training camp at Inverclyde. He took us under his wing and we often travelled out to Hamilton where John lived with his first wife Christine to help him collate training films and such like. On one later occasion, when we were both 17 I had bought a Honda motor bike but Hamish had splashed out on a wee scooter-type thing which barely went about 15-20mph. We both decided to go out to Hamilton to visit the Andersons on a particularly cold winter day. I got to Earnock about an hour before Hamish and when he appeared Christine had to take him into the house, place him in front of the fire, and thaw him out. I reckon he was suffering the first stages of hypothermia!

Our weekends were entirely taken up with training – usually meeting Anderson somewhere and then going to the new all weather running track at Grangemouth Stadium. Later on that changed to Meadowbank in Edinburgh. We were in an excellent group of athletes that John coached that included Scottish shot put champion Moira Kerr, hurdler Lindy Carruthers (her mother was a coach with Maryhill Ladies, but more of that later) 400m runner David Jenkins (later became infamous as a drug cheat but we always called him Gwendoline – can’t really remember why…) the decathlete Stewart McCallum, middle distance runners Dunky Middleton and Graeme Grant. There were others but I can’t remember them now

Hamish and I were training partners to some noted Maryhill Ladies athletes such as Avril Beattie and we benefitted from the extra training opportunities that training with the girls of Maryhill Ladies brought (eg Friday evening indoor gym sessions). By now my parents had moved and I had left West of Scotland to join Bellahouston Harriers but Hamish remained very faithful to West of Scotland Harriers. But it was Maryhill Ladies where his coaching would eventually start.”

How does Hamish himself remember these early days? He was asked to complete the questionnaire.

Hamish with Diana Brown and Jeanetta McPherson at Bellahouston in the Maryhill coaching days

Name: Hamish Telfer

Club/s: West of Scotland Harriers (coached with Maryhill Ladies AC)

Date of Birth: 28th April 1950

Occupation: University Lecturer

How did you get into the sport initially? “Ran for my Primary School in the relay team; then secondary school then joined West of Scotland Harriers.”

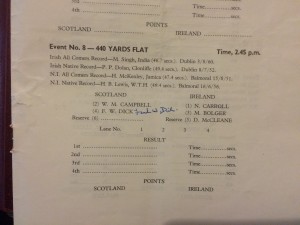

Personal Bests? “55.9 for 400m indoors at Cosford in 1967; 4m 12 for 1500 aged 18 – all very modest.”

Has any individual or group had a marked effect on either your attitude to the sport or your performances?

“I owe a great deal to the late John Todd of WSH and almost everything to John Anderson former Scottish National Coach who coached me from age 15 to 21. Must thank the late Jimmy Campbell and also Frank Dick for getting me started in coaching. Jimmy was a great inspiration. Later in my career there were a number of individuals from other sports from whom I learned but I have a particular affection and respect for both Bill Walker and Peter Warden in athletics and the late Geoff Gleeson (former GB National Coach for Judo) – all very wise and intelligent coaches.”

What do you consider your best ever performance as a runner?

“Not many but being in the WSH team that placed 3rd in the Scottish Youth XC Champs; that 400m indoors at the age of 16 and possibly the struggle to break 3hrs at Marathon in later life. As a coach – my first athlete Sandra Auld (nee Weider 100/LJ) with whom I made so many mistakes in coaching without realising; watching Lucy Elliott smash the English Schools 400mH record to win the Seniors and get her first England vest; Steve Watson win BUSA 10k track Champs; Rona Elliott(nee Livingston) over 400; Brenda Walker running at the Auckland Comm. Games in 1990; John and Suzanne Rigg over 400/800 and marathon respectively and probably all my athletes who always gave everything and why I had so much fun coaching. My contributions to coach education across the UK. Oh …. and the 5 World Championship wins with my GB teams in the World University XC Champs. from 1992 to 2004.”

What did you do apart from running to relax?

“Worked; brought up my daughter after my wife died; coach education work both in England and Scotland; hill walking and trekking; music (all sorts); reading – Scottish political history; philosophy and ethics and now cycling and cycle touring and at the age of (almost) 65, triathlon training.”

What goals do you have that are still unachieved?

“Very few. Probably to destroy all the other old gits in my first Tri and complete the Munros (only 20 odd to do). Keep cycling all over Europe.”

Can you give details of your training?

“More to do with my coaching and principles. Take care in developing the background for development; share your thoughts with your athletes on training and competition; develop a real ‘I can do anything’ mentality; immerse yourself and show them that you and them are a ‘team’ working to a common goal; have loads of fun; never be afraid to make mistakes and more importantly admit the cock ups; always remember that you will get to a point where the more you know – the more you know what you don’t know! Be reflective.”

Do you have any thoughts on current training and/or racing theories that you would care to pass on?

“I have always been a believer in good all round conditioning. All my endurance athletes for example went through coordination drills and agility work (with varying degrees of gracefulness and competency!); winter background conditioning was a very clear emphasis with me as it laid the foundations; I used a lot of basic exercises using the upper body as well as trunk; on track I guess I was not so different from other coaches other than I spent huge amounts of time getting my athletes into the frame of mind that anything was possible and doing this through high intensity work, modifying volume and duration as I thought necessary.”

What changes would you like to see in the sport?

“More of the coach focused approach which we are ‘told’ about actually happening; more attention paid to supporting clubs; a recognition that our population of children coming in to the sport are qualitatively and certainly ‘quantitatively’ different! It is now taking longer to get children and young people into a shape where they can even train competently.”

You also did some hill/mountain running. How did that come about?

“That was entirely the fault of my mate Cameron McNeish. We once did some local hill running as athletes because he thought it ‘would be a good idea’ (like his good idea to run to his aunty’s in Langbank and back from his house in Glasgow when we were schoolboys – 18 miles in one evening – I had rigor mortis for 2 weeks!). Later, in our early 30s he phoned me out of the blue and asked me to partner him in the Saunders Lakeland Mountain Marathon. While I died the death of a thousand dogs we did manage to win a sub category. Run most of the Scottish hills for fun after that.”

_____________________________________________

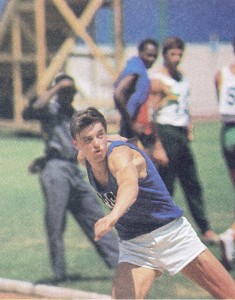

Hamish as a young National Coach delivering a session at Crystal Palace in 1976

We should maybe go back to what happened to Hamish after Maryhill Harriers and into employment. Cameron tells us that Hamish first thought about joining the police force, then decided to stay on at school and become a banker. Hamish tells the tale. “School and education eventually kicked in for me just as it was perhaps getting too late! After a disastrous series of O grades (just 3!) I stayed on at school after getting rejected for the Police Cadets (lack of height) and did my Highers. Cammie got in to the Police Cadets and I got enough Highers to get in to the Scottish School of PE at Jordanhill after a short spell in a bank as a bank apprentice.”

Hamish kept on competing and usually made the finals in the Scottish championships. He stepped up to the 800/1500m just as he left school and during the 1968 Olympics while doing his Highers, he changed his body clock to be able to go to school, do his paper round, eat, sleep and do his homework AND be able to watch the Olympics on TV every night. John had asked him to get the miles in before he came back from Mexico City so Hamish ran 1000 miles in three months because he thought it would be ‘a good thing,’ Unfortunately during his first year at Jordanhill he had a bad knee injury (in 1970 – his knee cap came out of joint), and John encouraged him to start coaching. He also started hill walking with Cammie and developed a love of the outdoors and canoeing. He even joined the Lomond Mountaineering Club and became their secretary for a while. The coaching developed, he graduated from Jordanhill and by that time he had a group of athletes including Sandra Weider, Mary Ingram, Lynn Doran, Jeanetta McPherson and a few others. He teamed up with Iain (Rab) Robertson and Jimmy Campbell at this point – a better pair of coaches you couldn’t find.

It was hard work at Jordanhill – ‘and Hamish worked bloody hard’, says Cameron, to gain the qualification, and left with a Dip. Phys.Ed with a merit in Education. During his last years at College, Hamish ‘consumed information as if there was no tomorrow’. He did have time though to represent the College at Volleyball and Hockey: although he is rather dismissive of the standard he reached, he was given half colours. Graduating in 1973, he decided not to teach in the Glasgow local authority but taught instead in St Columba’s High School in Greenock. Those were the days when teachers on graduation ‘interviewed the local authorities’ before deciding on which one they would work for. In my case I attended interviews with Glasgow, Dunbartonshire and Renfrewshire. Hamish chose Renfrewshire – St Columba’s was a school with well over 2000 pupils and Hamish introduced several initiatives with varying degrees of success:

* Tried to start an outdoors club – failed;

* started a swimming and life saving club – succeeded;

* helped coach the school volleyball club;

* helped in the school Gilbert and Sullivan productions; and

* worked as a part-time youth worker after school at the youth club

It is interesting in the twenty first century to note the range of activities being carried on in an ‘ordinary’ state secondary school. These were not confined to Hamish’s school, many schools followed a broader curriculum than is possible now and it probably helped develop Hamish as a coach. How so? Well, he was mixing with the pupils in all sorts of contexts – as an instructor, as a partner and as a friend as well as in a teaching capacity. There was a breadth of interaction that would have been difficult to replicate elsewhere. Of course, he also kept the athletics coaching going and (another initiative) changed the school sports day from one where only about 40 kids out of 2,200+ took part, to one where over 160 took part. This was done by making it ‘self competitive’ using the Thistle Award scheme.

But the one activity which had the biggest effect on his future was his activities in life saving. He took the school life saving team through to the Scottish National Championships in two consecutive years. Second time there he was asked if he would be interested in the role of National Development Officer for the BLSS – UK. Having had an application for promotion within Renfrewshire rejected, he just went for it and became what was in effect the post of National Coach. At the age of 24 he was the youngest National Coach in any sport in the UK. The two aspects of the job that could have been improved upon were location (it was in England) and sport (it was not athletics). Typical of Hamish, it was not to be the first time that he took on something that he knew only a little about and learned about it ‘on the job’.

Cameron McNeish again:.

“That got him involved in the whole national, and international, coaching structure and even when he was working as a life saving coach his heart was still in track and field. By this time he had his own squad of athletes and he dedicated a lot of time to them. I think John Anderson was his inspiration. Like Hamish, John wasn’t a gifted athlete but worked very hard as a coach. Hamish did the same. No-one worked harder than Hamish and he never asked his athletes to do anything he had never done. He knew what it was like to be sick by the side of the track, or to be so knackered he could hardly stand.”

He started with the RLSS on 1st January 1975 in England which meant that his athletics coaching had to stop. It had been going well, he had got his Senior Coach Award at the age of 23 and had a very good squad indeed. He stayed with the Life Saving until 1978 in the Midlands and North England and helped coach their GB squad for the World Championships held in London in 1976. He left the job when he got married and took up a post a Liverpool University as a Lecturer in PE and got started back in athletics when Rona Livingston asked him to coach her for a last try at making the Scottish team for the Commonwealth Games. She was an ex-pat living in Liverpool and started to do well. He quickly got a squad together and others joined in, including Donna and Bill Hartley, Ikem Billy and Rob Harrison. He was himself noticed and picked up and taken into the official system in the North West of England by Carl Johnson and Peter Warden as well as by Frank Dick. This led to him working in coach education for athletics and he began running the courses in the North West.

In 1981 he moved to Lancaster University and coached the University squads – the road racing team was particularly successful. He also ‘discovered’ Lucy Elliott who was only 13 at the time and she was to become his first GB athlete. He also dabbled in coaching hockey to such effect that the University team went up a league and he also coached the full Cumbria County squad. His athletics squad was now up to 15 athletes at one time across a range of events. Several of them were doing very well indeed – eg John Rigg, Brenda Walker, Steve Watson, Lucy Elliott and John Blackledge.

Drugs and doping were big issues in athletics at the time and suspicions about foreign athletes – particularly but by no means exclusively the East Europeans – were rife, Hamish was one of the few British athletics people to get involved. This was the time when David Jenkins was arrested in America and it became an even hotter topic as a result of that. Hamish, along with the late Ron Pickering and two journalists from ‘The Times’, Pat Butcher and Peter Nichols, worked on an expose of the British scene which was printed in ‘The Times’. There was even a lengthy correspondence in the pages of ‘Athletics Weekly.’ This led to the Coni Inquiry which found that there was indeed an issue that needed to be dealt with.

After reading for a BA at the Open University and then an M Ed at the University of Liverpool, Hamish became really involved in top flight athletics. I quote from ‘The Leisure Review’:

“Hamish consolidated his career at Lancaster within British track and field athletics, coaching a squad of athletes of which some 14 became British internationalists competing at World, European and Commonwealth Games levels. He was appointed GB Team Coach for the World Universities Cross Country Championships 7 times and the athletes he selected and worked with gained 5 world titles over this period in addition to numerous silvers and bronzes”

In 1991 he stopped coaching his personal squad when his wife died very young of cancer. His priority immediately became his five year old daughter. Despite his own unimaginable grief, he managed through his professional work to keep involved in coach education through research and courses which, being one offs were easier to juggle alongside his new family responsibilities. At this time he kept contributing to Coach Education across all sports. He worked for the National Coaching Foundation (which is now Sportscoach UK) and with the various Sports Councils. We have already seen that he had been working at international level with life-saving and athletics, and in 1995/’96 he spread his wings a bit further when he was a Great Britain Team Coach (Coach Support) for Wild Water Canoeing (remember that he started out with football and he has also been involved with hockey).

There were also many published articles and papers on Coaching, more Coach Education materials as well as ‘academic type stuff’ on coaching practice and generally got involved through that avenue. Academically he had seven main areas of interest and expertise – sport history, olympic studies, coaching practice, practice ethics, safeguarding and children’s values in sport. There are many of these papers available which indicate the consistent quality of his work. Even a cursory look over his publications on the internet provides extensive evidence of this. Five minutes timed with a stopwatch produced this:

http://www.theleisurereview.co.uk/events/HamishTelfer2.pdf

http://sccu.uk.com/news/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/SCUK-Analysing-your-coaching-article.pdf

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Books-Hamish-Telfer/s?ie=UTF8&page=1&rh=n%3A266239%2Cp_27%3AHamish%20Telfer

http://impact.ref.ac.uk/casestudiesapi/refservice.svc/GetCaseStudyPDF/21486

…. and there are pages more!

In 1991 he had been seconded to Charlotte Mason College in Cumbria as a lecturer in physical education for two years. Then in 1993 he moved to be Senior Lecturer in Physical Education at St Martin’s College Lancaster (which later became the University of Cumbria) – he held this post until 2010. At St Martin’s he was specifically tasked with setting up, with the existing two members of staff, a new Department of Physical Education and Sport, starting with a new degree in Sports Science, followed by degrees in Sports Studies, Coaching and Sport Development, the MA in Sport Coaching and Sport Development, and a degree in Leisure and Tourism. At this time he was also secretary and chair of the local branch of the University Lecturers Union and completed his PhD in 2006 at Stirling University.

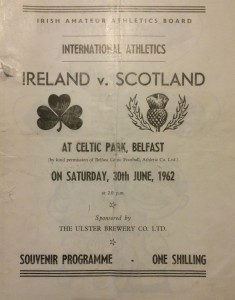

This period saw more sporting honours for Hamish as his talents and work-rate were recognised. For 12 years, from 1992 – 2004, he was Great Britain National Team Coach (Cross-Country) for the World Student Championships. Of this period he says : “The World Student Cross-Country was a terrific and privileged experience. There was only one championship out of seven where we did not return with medals of some colour. We won five World Titles between 1992 and 2004 (including an almost clean sweep of three out of the four in 1994) and a good number of silvers and bronzes. I was able to really apply some of the coaching concepts I had developed with the athletes involved. We clearly had the talent coming through as we were able to demonstrate. What happened after they left us …… !!!!?”

What happened after 2004 for Hamish was that he felt that after twelve years he had done his bit and stepped down.

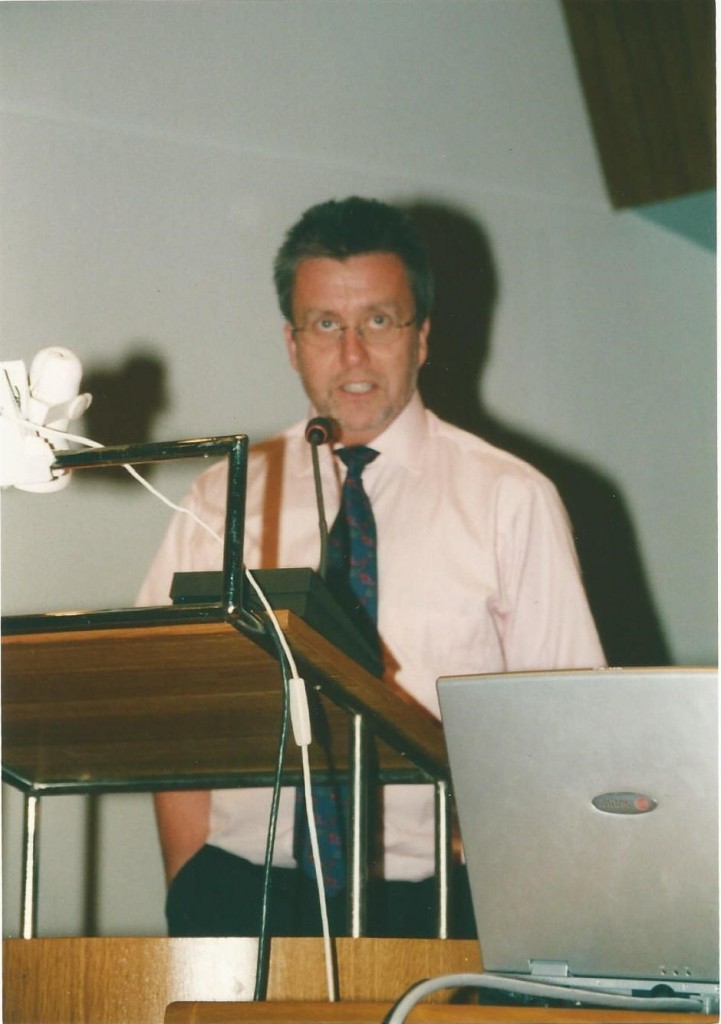

Addressing the International Olympic Academy, Olympia, Greece, 2003

Back at home in Scotland he was voted by the Scottish coaches to be vice-chair on the Scottish Coaches Commission and this pleased him greatly. The Coaches Commission worked hard but was ultimately unsuccessful – almost certainly for political reasons within the sport rather than through any failure on the part of the coaches involved. For an overview of his coaching career and some reflections on the period maybe a look at the second half of the questionnaire would be useful.

This produced the following comments.

“Were there any significant inspirational figures who influenced your coaching practice?

“No question about John Anderson. Also Jimmy Campbell and my young coaching mate Iain (Rab) Robertson who started around the same time as me. Alex Naylor was also a magnificent example of an inspirational and hard working coach who always encouraged in between making sure I never got too big for my boots with that wonderful sense of humour. Eddie Taylor also helped a lot.”

How far did your own running and competition influence your coaching theory and practice?

“John Anderson taught me about hard work and commitment. That has shone through all my own coaching. Never too bothered about whether an athlete was good or bad or had potential, but always hammered home that they had to work hard (at whatever level) or I wasn’t really interested. Great believer that if you give everything you can then there will be no ‘what ifs’.”

How did you get involved in coaching at national level?

“Partly due to Peter Warden, Frank Dick and Carlton Johnson. Also I had been a full-time GB National Coach in another sport and ‘returned’ to Track & Field. Got coaching a group in Liverpol; got involved in Regional Coach Education as a staff member then as the lead co-ordinator. Was involved with British University Sport where I met Malcolm Brown and we got on well (he asked me on to the Athletics Committee for moral support!); I had been to the Commonwealths in 1990 with an athlete and so in 1991 he asked me to work with him with the British Cross-Country team for the World Championships (I was already working with the English Students Team at Home Nations level). Thereafter it was Malcolm Brown and myself until about 1998 and then Chris Coleman became my team manager until I left in 2004.”

What Scottish, GB or University teams have you been involved with?

“One Scottish Junior team, numerous English University representative teams, Isle of Man team for a Commonwealth Games, and numerous GB University teams (mainly cross-country but also some track & field teams from 1992 until 1994.”

What Scottish, British or University International teams have you been involved with?

“One Scottish Junior team, numerous English University representative teams, Isle of Man team for a Commonwealth Games and numerous GB University teams (mainly cross-country but also some Track & Field teams from 1992 until 2004).”

Are there any coaches that you particularly admire – either coaching at present or in the recent past?

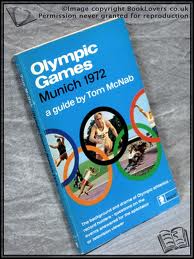

“John Anderson, Frank Dick for his achievements in trying to make ‘coaching a greater priority within the governing body, Tom McNab for his wide ranging skills, intellect and native cunning, Malcolm Brown for his abilities to transfer his coaching skills into Triathlon so successfully, John Mills for his thoughtful approach to coaching within British cycling, the late but wonderful gentle Geoff Gleeson of British Judo who spent hours talking to me as a young and very inexperienced National Coach, Trevor Clark who helped me think about my coaching via his sport of hockey and Peter Warden with whom I had some fantastic fun coaching our respective squads. I also had a lot of time for the late Patrick Duffy who tried to lead, develop and improve the structure of British coaching. Bill Walker has always brought a quiet confidence to his work and there are other coaching colleagues over the years including my colleagues on the late lamented Scottish Coaches Commission (including that wee fireball Eric Simpson). I will have left some out but all colleagues with whom I coached were part of how I thought and worked.”

Hamish retired in 2010 when he took ‘early retirement’ and has never been tempted back to coaching in athletics. He has done his bit and like many of us might have problems with the new bureaucracy in the sport: “I think I might commit homicide with various ‘professionals’ in the governing body at UK level.” He still does ‘bits and pieces’ and is currently involved with a club based piece of work with athletics clubs in the north west of England re the state of ‘technical events’ where we still have a problem. He is also still doing research work as what he calls a ‘semi retired’ academic. (And it seems to me that he has set up another ploy when he asks “What happened after they left us? )

Let him have the final word about life after coaching:

“Cammie McNeish and I have renewed our auld alliance with a vengeance by cycling. Done Lands End to John o’ Groats, France top to bottom, Ireland from bottom to top and this year we are about terrorise Spain. A bit like Compo and Cleggy in lycra or an old married couple (take your pick). If you see us, then feed us cake – we respond well to that.”

I mean, the second last word – you can read what some of his colleagues and athletes think at www.anentscottishrunning.com/hamish-telfers-friends/

The picture below of Hamish on his bike is from Cameron.