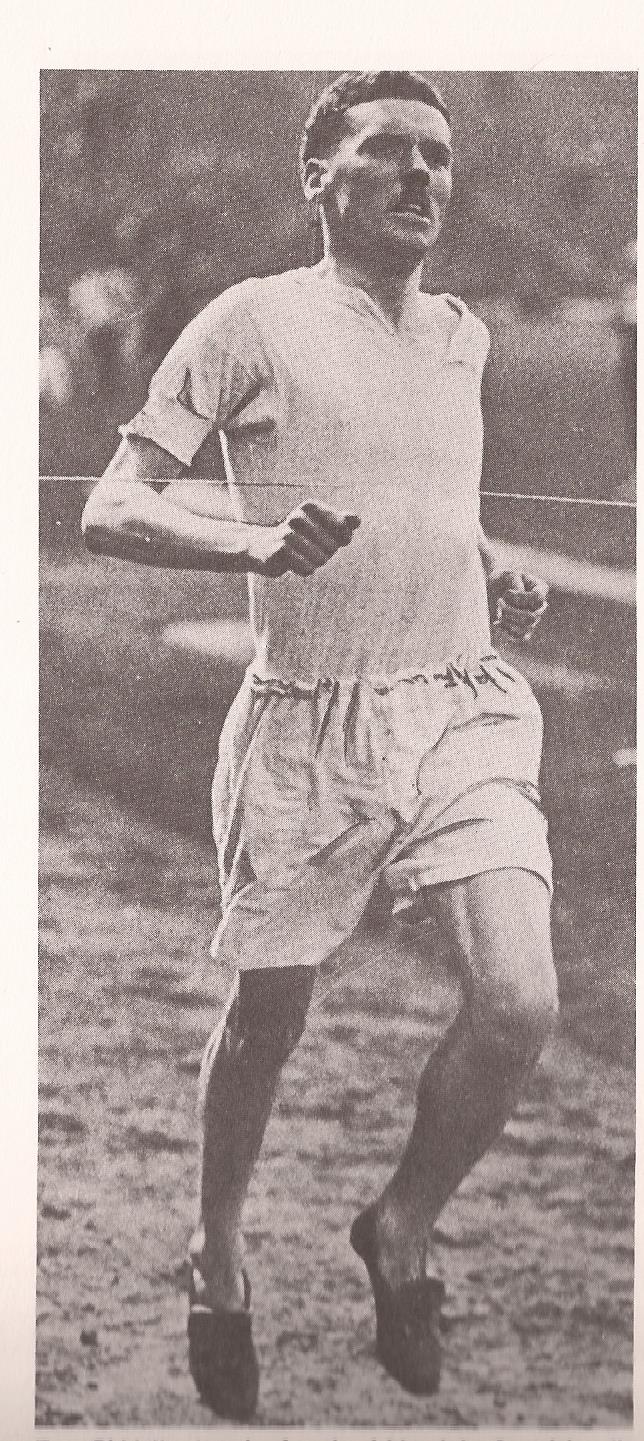

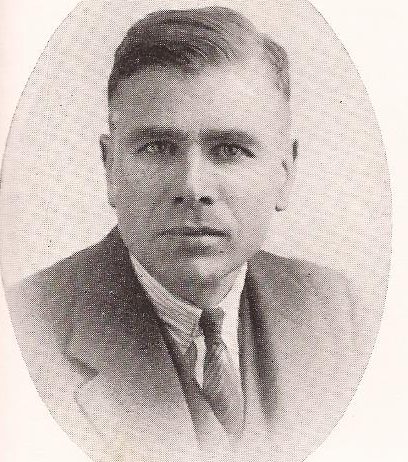

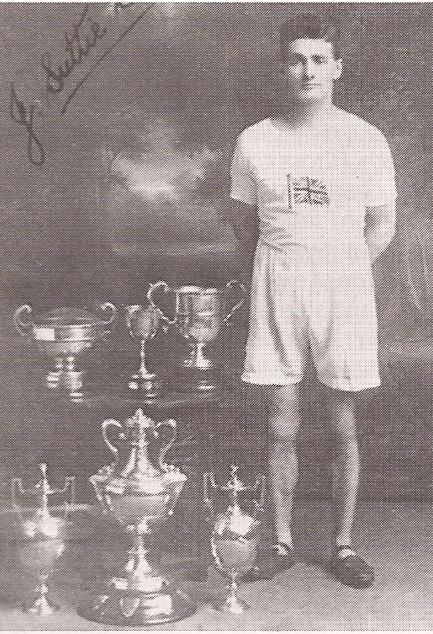

Tom Riddell was born in Dennistoun, Glasgow on 3rd June 1905 and was educated at Glasgow High School. He went on to win eight SAAA Mile titles between 1925 and 1935 – it would probably have been more because he was working in Cork, Ireland, in 1927, 1928 and 1929 and was unable to compete. A member of Shettleston Harriers, he first contested the championship in 1924 when he finished second to WR Seagrove who went on to win the AAA Championship in London a week later in 4:21.2. This first defeat could be put down to experience, or lack of it, against a class runner.

The following year Tom gained the first of eight victories when he won in 4:27.8. A very consistent runner he was never slower than 4:30 in his championship triumphs. In 1933 he set a championship best performance of 4:18.6. He had already lowered the Scottish record to 4:18.0 at the Rangers Sports in 1931.

The charismatic Riddell was one of the most popular athletes of his day because he was an out-and-out competitor and a man who liked to run from the front. In the Rangers Sports two years later he improved his mile record again. John Keddie says in his centenary history of the SAAA, “Alongside the Scot were the English cracks Reggie Thomas (RAF), the English native record holder at 4:13.4 and Cyril Ellis (Birchfield H) towards the end of an illustrious running career but still Scottish All-comers Record holder (4:16.2 in 1931) and the great New Zealander Jack Lovelock, who even before his great Olympic triumph was one of the world’s top milers. He was the British All-comers record holder (4:12.0 in 1932). Thomas led over the first lap of the race (61.0), shortly after which Riddell took over, leading the field through the half mile in 2:03.8 and three-quarter mile in 3:10.6. Tom held on grimly cheered on by enthusiastic fellow-countrymen, but could not hold off Lovelock’s irresistible burst in the home straight, and it was the New Zealander who went on to win by four yards from Thomas who was about the same distance ahead of Riddell with Ellis fourth. The times were outstanding: for Lovelock, a new Scottish All-comers record of 4:13.6. for Thomas 4:14.2, very near his best and for Riddell a new Scottish record of 4:15.0. Truly one of Scotland’s ‘miles of the century!’”

Apart from thrice setting a Scottish record he also set new figures for 1000 yards, the three-quarter mile (twice) and one and a half miles. His last public race was a real triumph. Having beaten Alf Shrubb’s British one and a half miles record of 6:47.6 (set in 1902) by six seconds at Largs on 15th July, he raced the distance again at Helenvale in Glasgow on 20th August and set a new record of 6:36.5. This stood for twenty five years before it was broken.

He only ran in the AAA’s championships once when he was third behind G Baraton (4:17.4) and Tom’s 4:19.0 was the fastest by a British runner for that summer season. A week later he won the Triangular International in a slow 4:30.8 in a tactical race against the 1925 AAA winner B Macdonald. He ran for GB several times with his fastest time being 3:54.2 for the 1500m in the match against Germany in Munich in August 1935 behind FW Schaumberg (3:53.9). This was estimated to be the equivalent of a 4:13.0 mile. He was short-listed for the Los Angeles Olympics in 1932 but had to turn down selection for business reasons.

He had a very good military career, surviving Dunkirk and retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel. He retired to Fintry and kept his interest in athletics with not a few letters to the ‘Glasgow Herald’ about the sport.

His career is beautifully covered in Doug Gillon’s obituary in the ‘Herald’ of 22nd August 1998 which reads:

Tom Riddell, athlete; born June 3, 1905, died August 16, 1998

TOM Riddell may not have been the greatest athlete of his generation, for that honour, he would concede unequivocally, belonged to his contemporary, the Chariots of Fire inspiration, the 1924 Olympic 400 metres champion, Eric Liddell. Yet Riddell, who died peacefully in a Stirling hospital on Sunday in his 94th year, and who was believed to have been Britain’s oldest surviving international athlete, won more Scottish titles, set more national records, and in his own right was one of the most remarkable and charismatic of this nation’s twentieth-century sporting figures. It was only when he burned his legs quite severely, two years ago, setting his trousers alight as he disposed of rubbish in the garden of his home near Fintry, that he was forced to restrict his recreational activities. ”You are supposed to be dead before you cremate yourself,” was his comment on the matter. Yet even after, until the onset of the cancer which finally killed him, he performed stretching exercises, walking and jogging several miles daily; and rode an exercise bike which he kept in the hall of his cottage – a natural continuation of the discipline which helped earn a record eight Scottish mile titles and a clutch of records at various distances in the decade from 1925. He flirted with the idea of a knee replacement, ”so that I can get back running again,” at the age of 91, but even the burns never quenched his spirit. He was a regular writer of letters to this paper on a range of issues – but often a commentary on the decline of traditional values. He resigned his honorary life membership of the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association because he despised their hypocrisy in retaining the word ”amateur”. Yet he applauded the relaxation in the rules which allowed such as Tom McKean and Liz McColgan, from working-class backgrounds, legally to earn the money without which they could never have run at all. Born in Dennistoun and educated at Glasgow High School, Tom McLean Riddell won the first of his mile titles at the age of 20, and would undoubtedly have won more but for a three-year absence, while working in Ireland. He set two Scottish mile records, the second (4min 15.0sec) at a packed Rangers Sports in 1933, when he finished close behind Jack Lovelock. The New Zealander was then the British all-comers’ record holder, and became Olympic 1500m champion three years later. Shettleston Harrier Riddell also set several records at 1000 yards, three-quarter mile, and one and a half miles. He was named for the 1930 Empire Games and 1932 Olympics, but rejected both because of work commitments. His last two recorded public races, in 1935, saw him take 11 seconds from Alf Shrubb’s 31-year old UK best for a mile and a half. What nobody knew was that Riddell, aged 40, after the end of the Second World War, ran for his regiment in a battalion race in Germany. Dragooned into it by his superior, he won the three-mile event. The officer confessed he had ”won plenty off the wee man, here, in a wager,” – Field Marshall Montgomery. Riddell’s superior, General Sir Brian Horrocks, confessed he had backed Riddell only to finish in the first 10. ”You’re hell of a generous, sir,” retorted Riddell. ”There were only 12 in the race.” Horrocks, however, presented Riddell with #5 from his winnings, sufficient to forfeit his amateur status. Riddell gave the #5 to his men, to buy beer, kept mum, and remained an amateur. He set his fastest 1500m time in a match between Great Britain and Germany in Munich, in 1935. Though narrowly beaten by FW Schaumberg, he clocked 3-54.2 – equivalent of a 4-13 mile, and faster than his existing Scottish record. That night, Riddell was in the Munich Hoffbrauhaus, when a stylish young Nazi introduced himself, chatted fluently in English, and departed clicking his heels as he presented his card. It was Rudolf Hess. Their meeting was to provide one of history’s ironic twists of fate. A Dunkirk veteran, Riddell picked up an extra rifle while being evacuated from the beach head. Soon after, when his brother-in-law in the Home Guard bemoaned their armoury of pitchforks and sticks, Riddell gave him the rifle. When Hess landed at Eaglesham in 1941, he was detained at the point of that very same gun. ”There was no ammunition in it, because I had none to give,” Riddell recalled. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and his decorations included a military OBE, and the Czech equivalent of the Military Cross. He was a JP and a fellow of the Institute of Highway Engineers, ending his working life, at 75, as managing director of the Glasgow firm of McCrea, Taylor. Even in his ninth decade, his boyish enthusiasm and sense of mischief remained unquenched, as he visited his long time crony, the former Scotland rugby player Jimmy Ireland, also in his 90s. Sweeties from Fintry’s famous home-made confectionery shop were always produced from his pocket for visiting kids, old and young. When asked to open a children’s play area in his native Fintry recently, he was asked by a local newspaper if he could manage to sit and pose on the bottom of the slide. Tom looked, amused, at the photographer, skipped up the steps, and gleefully wheeched down. He is survived by Jean, his wife, and their daughter, Jan.

Hugh Barrow sent the following from his collection of cuttings, photos and memorabilia – a tribute to one great Scots athlete from another.

Recollections of Eric Liddell By The Hon. Lt. Col. T.M. Riddell

In 1923, to most School Boys, Eric Liddell was a Hero and this was not misplaced because he turned out to be – and is – the Greatest Athlete that Scotland and indeed the World has produced.

In 1923 I was privileged to represent The High School of Glasgow, at the Scottish Schools ‘Inter Scholastic Sports’ held at Inverleith and this in the Mile race. Fortune favoured me to the extent that I was “first through the Tape.” As I left the Arena I was confronted by My Hero, Eric Liddell, who shook me by the hand and expressed the hope that I would continue in the Sport and that he would meet me at the Season’s Sports Meetings. This was the beginning of a friendship which lasted until the War when we lost touch with each other.

On several occasions at country meetings I ran the 880 yards leg in the ‘Medley Relay’ while Eric ran the 440 yards leg.

Apart from Sports Meetings I met Eric with his Great “Guide – Philosopher and Friend” Neil Campbell, a fellow student who became Professor of the Faculty in which he and Eric qualified. Another of Eric’s co-operators was the Rev. D.P. Thompson, together they held seasonal Evangelical Meetings in Edinburgh and at Montrose Street Church in Glasgow. Those meetings were crammed to the door by two generations of young people.

So much has been recorded about Eric’s Athletic Achievements but they were in fact, as far as he was concerned, a Catalyst in the formation of his character and his perceivable Missions in life, which were:-

“To walk humbly with his God

and

to fulfill the ‘New Commandment'”

Gospel of St. John

Chapter 13,

Verse 34.

Note:

A great deal, due to his influence, I was “first through the tape” eight times in the Scottish Mile Championship and represented Great Britain Internationally over that distance on many occasions.

Thanks, Hugh