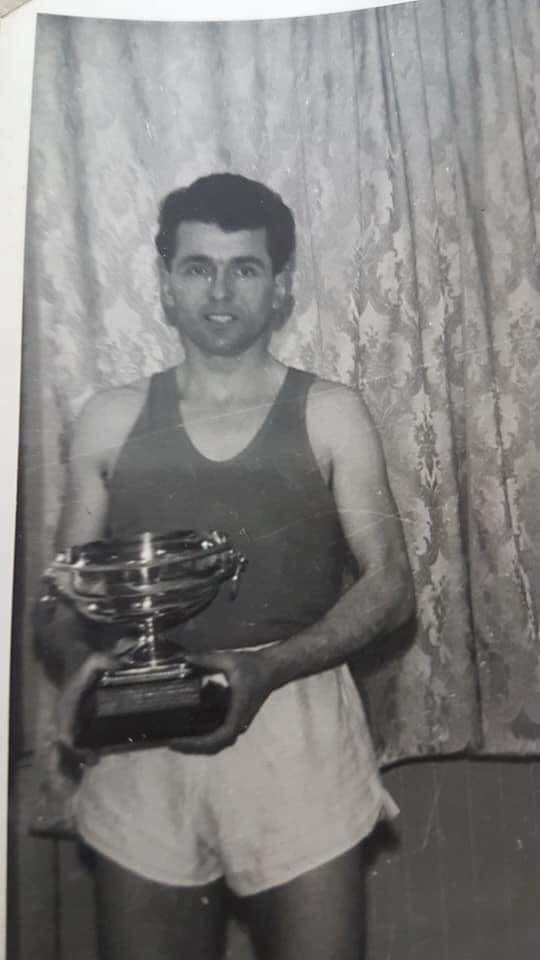

“Jim was one of the four pillars of the club with Andy McMillan, Dan McDonald and John Morgan” (Alex Hylan)

Jim Shields in the centre

Jim is in the dead centre of this photograph taken in the late 1930’s in the basement of the Bruce Street Baths in Clydebank. behind and to the left of Little Johnny Morgan. Jim did not appear in many portrait pictures or photographs where he was the main focus, but he was always there and always in the background. Never a seeker of the limelight, he was one of the best and hardest workers in Scottish athletics at a time when it was blessed with hard working officials. He is included here partly because of that but also because his time in the sport covered the immediate pre-war period when numbers in all clubs were low and Committees had to work hard to keep the clubs going, and the post-war period when the sport was starting up again, and on through to the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh and beyond. His career is a kind of chronicle of the sport for that period.

Jim Shields joined Clydesdale Harriers in the 1930’s and was one of the men who kept the club ticking over during the hostilities. He started as an office bearer during the war when he was club assistant secretary in 1939, after the war he was treasurer from 1946, and finally secretary from 1967. You will note that both were serious working positions in the club and to my mind it was unfortunate that he did not ever occupy the position of club President. His brother Arthur was also an office bearer in the club

Jim was also one of the best and best known officials and administrators at National level in Scottish athletics. He officiated at local meetings, Championships, international fixtures and at the Commonwealth Games. As an administrator he would surely have been President of the SAAA had his job not sent him abroad when he was Vice President of the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association where he had also served on many sub committees. A lot of his correspondence, notebooks and some commemorative medals are included in the Clydesdale Harriers archive in the Clydebank Public Library which will soon be available to the public.

Having been a committee member before the war he first held high office in the club when he was elected secretary in 1944 and at the first post war AGM in September 1945 he read his first secretary’s report. In it he said “he thought the club was definitely round the corner on the way to a revival. There was now a membership of approximately 50 (excluding those in the services), about 18 of those being Juniors. Attendances at the track had been quite good and a lot more like normal times. We had managed to run a points competition for the Youths and the winner was Thomas Tait with 10 points ahead of Sam Wotherspoon on 9 points and two more on 8 points. As regards the season coming on he said the SCCA proposed a full programme of races and he hoped the club would manage to run some of the usual races and he hoped for a good turn out at training and at Saturday runs.” His career as an official would carry on from that point. More used to being treasurer he was elected to that post the following year.

Described by one of his contemporaries as ‘one who was always there, not much of a runner but always turned out to support the club’ and described by Alex Hylan as ‘a real nice man, Jim was always polite and helpful to the members.’ The club in this period were always thinking of ways to raise money and Alex, as Assistant Treasurer suggested that the club get a Co-operative Cheque Number. The Co-op had a system whereby regular shoppers had a number that they quoted when they made a purchase and received a receipt when they left the shop. At the end of the year, each member received a cash dividend depending on how much they spent and what the percentage was that year. Jim took it up with gusto. He would harangue the members to use the number for the benefit of the club. Jim Young apparently got into trouble with his Mum for using the Harriers number instead of the family number: they were short of cash too! The club made some money from the scheme though. Willie Wright bought all his training needs through the club number at the Co-op.

This picture taken just after the War shows Jim with a group of club members at Mountblow – Andy McMillan is at the left in the back row with John Morgan, who was in Burma during the War, standing on the right with Jim in the white shirt on the right of the back row. It is a remarkable photograph – taken on the spur of the moment with a simple box-camera immediately after the war with the sun shining, some of the men had been involved in the hostilities but the country had triumphed and spirits were high A contrast with the dreadful atmosphere after the first war.

Jim was the club representative on the new Dunbartonshire Amateur Athletic Association committee for many years but he was a regular and well-kent face on the National scene as well. He was the representative to the SAAA for several years and worked his way up to vice president and, as was the custom, would have been the next SAAA President when in 1961 he was sent by the Singer Factory to their plant in India. He had a very responsible position in Singer’s factory in Clydebank in the finance department. He was involved in the introduction of the Time and Motion Study System to the factory which was not a popular innovation at the time. When the Indian branch was opened up, Jim was the man who went and unfortunately missed out on the chance of the highest position in Scottish Athletics at the time. The ‘Clydebank Press’ reported “On Wednesday evening at the monthly committee meeting a little ceremony took place. Treasurer Jim Shields was present to say ‘au revoir’ to the club prior to his departure for India on behalf of the Singer Manufacturing Company for a period of possibly three years. President D Bowman in presenting him with a fountain pen as a token of esteem from club members said that Jim had served the club faithfully for 27 years. He was the perfect example of an enthusiastic club member, in his earlier days as an active club runner, for the past 17 years or so as first club secretary and then treasurer.

An additional job which he undertook was that of correspondent to the ‘Clydebank Press’ where readers will better know him as ‘The Whip’. Mr Shields in replying thanked him and the club and assured them that the Clydesdale Harriers would always take highest place in his affections. He also said that in his opinion we had one of the happiest clubs in the sport and as long as that spirit prevailed we would never fail.”

When he had successfully worked for the company in India and Iran, just like a multinational company, when he returned his job had been given to another and he was looking for work.

Jim was very quiet and never pushed himself forward but if we look at his record in it totality we get the following remarkable record of service to the club – and note that it does not include time spent as Assistant Treasurer or Assistant Secretary:

|

Year |

Office |

Year |

Office |

|

1939 |

Assistant Secretary |

1957 |

Treasurer |

|

1940 |

Secretary |

1958 |

Treasurer |

|

1941 |

Secretary |

1959 |

Treasurer |

|

1942 |

Secretary |

1960 |

Treasurer |

|

1943 |

Secretary |

1961 |

Treasurer |

|

1944 |

Secretary |

1962 |

India |

|

1945 |

Secretary |

1963 |

India |

|

1946 |

Treasurer |

1964 |

India |

|

1947 |

Treasurer |

1965 |

India |

|

1948 |

Treasurer |

1966 |

India |

|

1949 |

Treasurer |

1967 |

India |

|

1950 |

General Committee |

1968 |

Secretary |

|

1951 |

General Committee |

1969 |

Secretary |

|

1952 |

General Committee |

1970 |

Secretary |

|

1953 |

Treasurer |

1971 |

Secretary |

|

1954 |

Treasurer |

1972 |

Secretary |

|

1955 |

Treasurer |

1973 |

Secretary |

|

1956 |

Treasurer |

1974+ |

General Committee |

Almost immediately on his return he was warmly welcomed back into the club – and on to the Committee for second stint as Secretary. The lesson for all future Committee Members is maybe not to do a job too well or it’s yours for good! The War Time Committee went on to organise a series of top class events and James P Shields was involved with every one of them. When the SAAA held the international cross-country championships in Clydebank in 1969, Clydesdale Harriers was seriously involved and Jim was one of the men who helped make it so. But the club was also involved in bringing to Clydebank such events as the Scottish Schools championships, the British Schools Cross-Country Championship, the Scottish Women’s Cross-Country Championships and and the Scottish Veterans Cross-Country Championships. Jim was a lynch pin in the organisation of those.

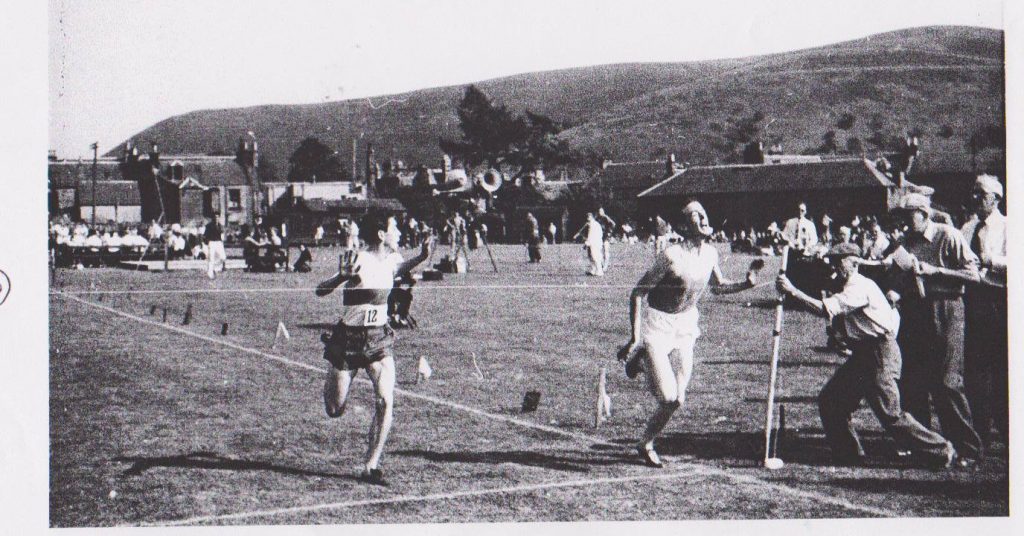

On the track,he officiated at both Edinburgh Commonwealth Games, at several International and Invitation Meetings across Scotland and was at almost every track and field sports meeting or amateur highland games held in the country at one time or another – at many of them he was an annual fixture.

A good and conscientious club man and a superb administrator, the club was fortunate to have Jim as a member. Even after he ceased work on the Committee through illness he still came to several club races and there were also donations to the club for many years.

In the picture below, taken at Whitecrook in the 1970’s, Jim is on the right with Jimmy Young (left) and Frank Gemmell at Whitecrook running track. All three were top class officials at local and national level – Frank sorted out the cross-country trails for all the major races, including the 1969 international and officiated in the Games while Jim was club president when the Schools and other internationals came to Clydebank and also worked at the Commonwealth Games.