Author: Admin

Paavo Nurmi Comes To Ibrox

Many of the world’s best athletes have run and raced in Glasgow. The Rangers Sports attracted stars in all events, the SAAA Championships have had some top stars appearing in the 1990’s when the ‘open’ nature of the event was being emphasised. We have had our own top runners of course – from Halswell and Liddell to Wells and McColgan. But there is one of the very, very best of all time who ran in Scotland and we are by and large ignorant of the fact. I speak of Paavo Nurmi the famous Finn. He did come to Glasgow and did run here with distinction – it was not for the appearance money. Alex Wilson has written the following article about the visit and provided the photographs. I’d like to thank him for the work done to produce this fascinating piece of memorabilia. .

Glaswegians have witnessed some iconic athletic moments down the years, such as at Ibrox in 1904, when Alfred Shrubb, the little Horsham wonder, demolished the world hour record as well as all amateur records from six to eleven miles.

This year (2013) denizens of Glasgow relived some of the excitement of earlier days when the amazing Ethiopian runner Haile Gebreselassie visited a revitalised Glasgow for the first time and won the Great Scottish Run in a new master’s world record for the half marathon. Altogether Alfred Shrubb set 28 world records during his career, including two world cross-country titles, but unfortunately never had the opportunity to cover himself in Olympic glory.

Haile Gebreselassie, between 1994 and 2009, set 27 world records at distances ranging from 2000 metres to the marathon, not counting the three masters’ world records which he set this year in the 10k (28:00), 10 miles (46:59.9) and half marathon (1:01:09). Many now consider the Ethiopian to be the greatest distance runner who ever lived, and this may be so, but like every generation of distance runners past, present and future, he stands on the shoulders of giants.

Without doubt, Alfred Shrubb and Haile Gebreselassie were the world’s foremost long distance running exponents of their day. They dominated their event like few others have before or since.

One of those few others is, of course, the great “Flying Finn” Paavo Nurmi who, like Haile Gebreselassie, came to Glasgow in the twilight of his career and, like Alfred Shrubb, left an indelible footprint on the cinder track at Ibrox Park.

Athletics is based on facts and figures, and on that basis Nurmi arguably ranks equal to Haile Gebreselassie.

Paavo Nurmi was undoubtedly the most successful of this stellar trio in the Olympic arena at least, amassing an incredible nine gold medals and three silver medals between 1920 and 1928. He might well have increased his unprecedented gold tally in Los Angeles had the IAAF not intervened and prevented him from running on trumped-up charges of professionalism.

Nurmi was no less prolific than Shrubb or Gebreselassie, setting 29 world records at distances racing from the mile to 25 miles between 1921 and 1932.

However neither Shrubb nor Gebreselassie had as profound an impact on racing and training methods as the Finn, who was truly ahead of his time in several respects. Nurmi was the first runner to adopt a scientific and holistic approach to training and race preparation. It is thought that he was the first runner to do interval training as part of a systematic twelve-month training regimen. His easy stride, high arm action and clockwork regularity were the product of years of hard training and meticulous attention to detail. He also pionereed the even-paced approach to racing and was famous for running with a stopwatch in hand. Many of his world records reflect his extraordinary pace judgement. He even had a special diet and practised vegetarianism for a while.

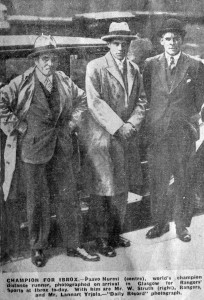

Nurmi (centre), Struth (right)

After it was announced in late July 1931 that Nurmi would compete in the Glasgow Rangers Sports on Saturday 1 August, the city was buzzing with excitement. Just the previous weekend he had established a new world outdoor record for two miles in Helsinki, in the process becoming the first man to break the nine-minute barrier. The Rangers’ manager “Billy” Struth had truly surpassed himself by bringing the world’s greatest distance runner to Ibrox.

Imagine the impact Usain Bolt might have next year if he comes to Glasgow and competes for Jamaica in the Commonwealth Games.

Nurmi arrived in Glasgow on the eve of the Rangers Sports and was suitably impressed by the condition of the track after a two mile canter complete with stopwatch and dressed in a loose fitting sweater and training pants, declaring it the best track had yet set his eyes on in Britain.

A huge crowd of 50,000 spectators – a record for a Scottish meeting – turned out the following day. Afterwards athletics aficionados would be unanimous in agreeing that there had never been a finer meeting in the long and successful history of the Rangers Sports. Four records went by the board that afternoon.

First, Tommy Riddell, of Shettleston Harriers, broke his own native record for the mile by 3 seconds with a time of 4:18.0 set when winning the handicap off twenty yards, then running on to complete the full distance, while in the same race Cyril Ellis , of Birchfield Harriers, returned 4:15.2, which was three-fifths better than Albert Hill’s all-comers’ record at Parkhead in 1919.

For all that, Paavo Nurmi was undoubtedly the main attraction, his event being a specially framed four mile handicap. Alfred Shrubb’s British and Scottish all-comers’ four mile record of 19:23.4 was Nurmi’s chief goal, and it was expected that the would probably come close to his own world record of 19:15.6.

The track had been specially prepared for the record attempt and the weather conditions were ideal.

Nurmi covered his first mile in 4:45.4, during which he failed to made much impression on Jimmy Wood, with 200 yards start, who was busily pounding his way round the track, himself intent on setting a record. The Finn passed the two mile mark in 9:41.6 and on completion of three miles in 14:36.0 had only made up 8.2 seconds on Wood. The Heriot’s F.P.A.C. runner put up a brilliant performance to take two-fifths of a second off the previous native record for the distance, set in 1904 by John McGough (Bellahouston Harriers), the former Greenock postman and now a farmer in Ireland.

Realising that he was behind record schedule, Nurmi piled on the pace in the last mile, to such effect that he made up twelve seconds on Shrubb, clocking a new British all-comers’ record of 19:20.4. Meanwhile, Tom Blakely, of Maryhill Harriers, took full advantage of a 400-yard start to win the handicap in 19:11.6, beating Walter Beavers, of York Harriers & AC (200 yds. start), by 15 yards.

Wood, beating 20 minutes for the first time, ran home third in 19:50.4, ten yards ahead of the the fair-haired Finn , but 5.2 seconds outside the Scottish record by Arthur Robertson, of Birchfield Harriers.

Later in the afternoon Nurmi went out for the record at two miles, but was clearly tired after his earlier exertions and never got anywhere near the leaders or the record.

The following year Nurmi elected to do the 10,000 metres and marathon at the Los Angeles Olympics. In late June he smashed the world record for 25 miles in the Finnish trials with a time of 2:22:03.8. He was made a strong favourite for gold in LA, but was denied the opportunity to win a tenth gold medal by a rather dubious and politically motivated eleventh-hour ban passed down by the IAAF on grounds of professionalism.

The Ibrox sports of 1931 were the last time Britons would see Nurmi running in their country.

You never know, maybe there are still a handful of nonagenarian or centenarian Glaswegians around who can still remember when the great “Flying Finn” caused a furore in their city.

Nurmi signs the drummer’s big drum

Nurmi signs the drummer’s big drum

Thanks, Alex, for a fascinating report on a great, but virtually forgotten, occasion.

Alex Dow

Alex Dow should be better known than he is. He ran for Kirkcaldy YMCA in the 1930’s, won the SAAA 10 miles track race, ran for Scotland in five international championships and was always in the first three counters at a time when the Scottish team won more medals than in any other decade. The fact that his club was never ever right up there in the rankings or championships of course might have contributed to the ignorance of his career – nowadays he might well be recruited one way or another to a more fashionable club, but in his day good runners ran for their own clubs and were happy to do so. A native of Collessie, he lived in Dysart and died comparatively recently – in 1999 at the age of 92.

A local paper remarks on his start in the sport: “He had rather an amusing baptism in the sport. While with the Black Watch at Perth, he was sent out with a squad to the North Inch and told to run a mile. He won. After that, Dow won several races in the Army. After his discharge from the Army, Dow joined Kirkcaldy YMCA and speedily made his mark.”

He ran cross-country running in the winter of 1933/34 where he did well enough to win the Eastern District title and also took the Scottish Junior title. Colin Shields in “Whatever the Weather” comments that “Alex Dow (Kirkcaldy YMCA) ran away from his rivals to win the Eastern District title by almost a minute at Musselburgh racecourse, the first of many successes that included an ICCU international bronze medal just two years later.” Of the National he commented that he ran well to finish fifth and win the National Junior title. The international that year was held on home soil – at Ayr – and there were hopes for a Scots victory but according to Shields, they were simply ‘run off their feet ‘ after a fast start. Dow in 12th place was the third Scot to finish behind Flockhart (6th) and Sutherland (11th) to gain a bronze team medal.

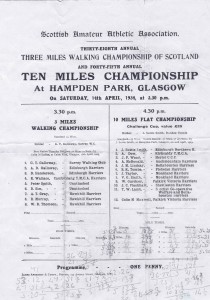

He really sprung into prominence, however, on 14th April 1934 when he won the SAAA 10 Miles Track title. The “Glasgow Herald” reported on the race as follows: “J Suttie Smith, the champion was indisposed and did not defend his honour. A Dow, Kirkcaldy YMCA Harriers, the Scottish Junior and Eastern District Cross Country Champion, gave further evidence of his capabilities by winning rather easily. The champion was the only absentee of the 12 entrants for the 10 Mile Race. Once the runners settled down, it was seen that JC Flockhart, the Scottish Cross-Country Champion, A Dow, SK Tombe and JF Wood had the title in their keeping. They ran in the above order for seven and a half miles, at which point Dow went to the front for the first time. Flockhart and Tombe were close up at this stage but Wood had dropped back and seemed out of the running. Once in the lead Dow drew steadily away. Running strongly and in effortless style, the Kirkcaldy man went on to win his first SAAA title by some 200 metres. Tombe also finished strongly to beat Flockhart by 50 yards. The intermediate times were:-

One Mile 5 min 11 2-5th sec; Two Miles 10 27 3-5th; Three Miles 15 min 46 2-5th sec; Four Miles 21 min 07 sec; Five Miles 26 min 27 1-5th sec; Six Miles 31 min 32 2-5th sec; Seven Miles 37 min 13 1-5th sec; Eight Miles 42 min 36 sec; Nine Miles 47 min 51 4-5th sec.

1. A Dow 53:12; 2. SK Tombe 53 min 40 2-5th sec; 3. JC Flockhart 53:49.

Alex Wilson, who gave me a lot of the information for the profile (and who in turn owes a debt of gratitude to Don Macgregor, who is not only a great runner but an athletics historian), has been good enough to send me a copy of Dow’s own extract from the race programme with splits taken on the day by one of his entourage.

As Alex says, with splits of 26:27 and 26:54 he wasn’t a bad judge of pace. When it is borne in mind that his club did not have access to proper track for training, it is remarkable that the pace should be so even – the YMCA trained in the Beveridge Park, on grass, meetings were evidently held in Stark’s Park too in those days, but the harriers obviously didn’t have access to a cinder track.

In the following cross-country season, 1934-35, he won the Scottish YMCA championship, and then Dow was seventh in the National behind Wylie (Darlington), Flockhart, Suttie Smith, Freeland, C Smith and William Sutherland. Excellent company to be in. In the International on 23rd March in Paris, he was second Scot to finish when he crossed the finishing line in tenth place with only Wylie (second overall) ahead of him. Flockhart, Suttie Smith and the rest were behind him: the “Glasgow Herald” simply said “Alex Dow (Kirkcaldy YMCA and 10-mile champion) again rose to the occasion, gaining ground steadily to finish tenth.” The local paper described it as a “Splendid, judicious race.”

Into summer 1935 and Alex was again competing in the SAAA 10 Miles track championship: this time he finished third behind Willie Sutherland and Jimmy Flockhart. He gained another medal in the National Championship at the end of the cross-country season when, according to Shields, he was as far back as thirteenth at one point but came through to be third at the finish. About the International in Blackpool, we read , “Alex Dow in all his five Scottish international appearances in the 1930’s, was never outside the first three scorers for the Scottish team, displaying a natural ability that gained him many victories without any great training schedule or hard work behind him. In the 1936 international Dow was at his best over flat fast course with scattered artificial obstacles. He was part of a team that included three men – J Suttie Smith, RR Sutherland and WC Wylie – who had all finished runner-up in recent years, but the main Scottish hope lay with James C Flockhart who was undefeated all season. The race was run in blazing hot sunshine and Dow, accustomed toi the torrid heat from his Army service in the Far East, was more at home with the weather than his colleagues. Starting in tenth position after the opening rush, he was eighth at half distance, sixth at 6 miles, and a relentless surging finish brought him home third, just six seconds behind Jack Holden, a three times winner, with British 6 and 10 miles record holder William Eaton finishing a clear winner by a 150 yard margin.”

1936 International Cross-Country Championship: Dow is Number 55

A local paper at this time described his training: “Dow trains on Tuesdays and Thursdays over the road varying his distances from three to five miles, and covers seven miles over the country on a Saturday. Dow does not bother himself unduly about diet, and ha so far failed to set for himself any special course of training for big events – more proof of his natural ability. No present day runner covers the ground with less effort. If one carefully watches his striding methods, it will be observed that his leg lift is of the minimum height, reminiscent of the style of the great Arthur Newton of South Africa who holds many long distance road records.”

If his selection for international duty so far had been eminently clear cut, this was not the case for 1937. He finished 102nd in the National at Redford Barracks in Edinburgh and was selected to run for Scotland. It had been the case that the first six were automatically selected and I don’t know of any runner finishing outside the first 100 to be picked for the International. Alex Wilson has looked into this carefully and has this to say: I have found some interesting stuff on Alex Dow’s selection for the 1937 ICCU Championship. It seems that it was the subject of heated debate. Many felt that the running order in the national championships should be the sole criterion for selection rather than the, in part, discretionary selection method favoured by the SCCU. According to Athlon (an athletics journalist) ‘This year the Scottish officials accepted the first three men – Flockhart, Farrell and Sutherland – without discussion, but all the others were put to the vote.’

One item (source unknown) re the Scottish Cross-Country Championships states: ‘The most remarkable failure was that of Alex Dow of Kirkcaldy YMCA. During the season Dow has hardly shown the form expected of him, but few looked to see him fail to finish inside the first 100. The Union, by including him in the team for Brussels, have shown they keep their confidence in him, and certainly his distinguished service in the past gives a guarantee that his form on Saturday was a temporary lapse. Dow may make a good recovery at Brussels.’

Another item states: ‘One of the most distracting features of the Redford race was the running of Alex Dow, Kirkcaldy, who finished only 102nd. His loss of form seems inexplicable, but bearing in mind his brilliant running for Scotland in previous races, the selection committee has given him a place in the team again.’

Athlon wrote re the ICCU selections: ‘I do not think the team is open to much criticism. the selectors have evidently chosen A Dow on the strength of his last season’s running, when he finished third in both Scottish and International championships. I believe the Dysart man has been troubled by a leg injury, obviously he was not fit on Saturday, for more than a hundred competitors beat him. I am not finding fault with the Union selectors in finding a place for Dow, but I think they are being rather inconsistent. Only a couple of years ago they left out RR Sutherland because he only finished 26th in the national event. Last year however, they chose WC Wylie after he had run 44th in Lanark, and he did not let them down in Blackpool’.

The 1937 International team – Dow on the extreme left

The 1937 International team – Dow on the extreme left

So how did he do in the international after so much ink had been spilt over his selection? Second Scot across the line, in 17th position, beating RR Sutherland by three places! The story of the day however was not his return to top form but rather team mate Jim Flockhart’s victory. Read about it here. The “Glasgow Herald” after devoting almost all of the report to Jim Flockhart had a paragraph that said: “Alex Dow fully justified the confidence of the Scottish selection committee. In finishing 17th he was second counting man for his country, beating RR Sutherland by three places. JE Farrell “stitched” badly at one point of the race but hung on grimly and eventually finished 23rd and fourth for Scotland.”

Alex Wilson’s comment is that “in the 1930’s at least the Scottish selectors had an uncannily good hand. These were clearly people with their ears close to the ground.” My own perspective is that at present selectors find many ways to avoid actually having to select a team – automatic qualifications, rigid trials, etc – and the thought of picking a runner who had been out of the first 100 in the national would be a boldness too far!

1937/38 was Dow’s last year and the 1938 international was his last. The national was to be held at Ayr in 1938 and 30 prominent runners were invited by Captain WH Dunlop to go for a training run over the course to familiarise themselves with it before the actual race. The race was on the same day as the English national so RR Sutherland missed it as did WC Wylie. John Emmet Farrell won the title by 150 yards from ‘a fresh looking Alex Dow‘ and PJ Allwell (Ardeer). The international was held at the Balmoral Showgrounds in Belfast where the Scots all ran poorly. Dow was 27th and third Scot. Some Press reports said that he had been second in the national despite not having trained hard and the Glasgow Herald report on the international, after lamenting the poor form of the Scots generally and the disappointing team performance had this to say of Dow: “A Dow found conditions against him and, in extenuation of his failure, it is remembered that he rarely does well except in fine weather and on firm ground. The race at Belfast was run in driving rain.” That is consistent with the reports of his run in 1936 where it was reported that the hot weather and blazing sunshine had suited him after his Army service in the Far East. He was however third Scot to finish.

He ran in other races – eg two weeks before the international he ran a fast time for his club in the Perth to Kirkcaldy Road Relay – but his international career was finished. If you look at any of the team photographs you will see that, along with RR Sutherland, he was the tallest in the team – probably over six feet – and it is no surprise to find out that he was a policeman. He took up a post in Palestine in 1939 his running career, as far as we know it, was at an end.

Like many of his generation, Dow was a very talented athlete who had a short career – the length of which was dictated by his occupation, it was terminated by his occupation too. If we look back at his ten miles triumph in 1934, the pace judgment was immaculate and in most of his races he tended to run steadily throughout and come through dramatically when others were tiring. This was done without the assistance of pace training on a track although it is possible that his road runs were what we would today call ‘tempo runs’! The country was blessed with many fine athletes in the 1930’s – possibly a golden generation?

Some Tributes …

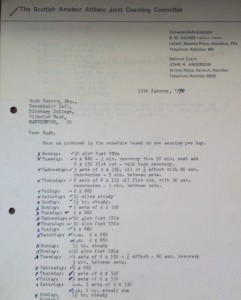

John Anderson has had many athletes pass through his hands and they almost universally have good memories and entertaining tales to tell, Some of these tributes are set out here – appreciations of help given and friendships made and maintained. I await more which will be added once I have seen them. First of all there is Dave Hislop who has known John since the early 1970’s. Dave ran for Edinburgh AC and Birchfield Harrierss with pb’s of 53.08 for 400m Hurdles and 49.25 for 400m flat. He ran for Scotland no fewer than 10 times between 1978 and 2004. Details of his career can be found at

http://www.scotstats.com/sats/uploads/ARCHIVE%202013/Final%20Profile-Men%20G-L.pdf

He says:

John Anderson -A Few Words! Perhaps a contradiction of terms but here goes…

I have had the privilege of knowing John for some 40 years during which time he has fulfilled a number of role in respect of me and my family ranging from coach, friend, employer, mentor, confidant, advisor, godfather to our son to mention but a few. He is undoubtedly one of the few people I know who is capable of carrying out all of the above and more…

Without his influence there is no way I would have achieved what I achieved in my sporting career or my professional career. John is the type of person who gives people the skills to enhance their life it is then up to them to take these opportunities.

The sheer number of international athletes John has coached not to mention those who may not have attained international level but who reached heights that they would not have achieved without John’s guidance, speaks for his prowess as a coach.

I could write a book on the experiences, as could the hundreds if not thousands of others, I have shared with him over the years and still continue to do so but this is not the purpose of these words.

I would like to take this opportunity to publicly recognise the impact John Anderson has made on not only my life but the lives of my wife, Kay and son, Jordan. The world of athletics has certainly benefitted from his input to the Nth degree.

To finish then I would just like to say a massive thank you John for all you have done for me and my family and also from those who have been fortunate enough to have been part of John’s life.”

It’s a sound testimonial to John’s ability to inspire and educate in a way that is not narrowly focused on sporting success, but to go a wee bit further than that – or maybe a big bit further!

***

Second up is Lynne MacDougall whose career is documented at www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.co.uk in the section entitled The Milers.

“I first met John in Portugal at an International Athletes’ Club training camp in the spring of 1983. John had organised a paarlauf session on the cross country course for the endurance athletes there. As usual he was very enthusiastic about the session and turned it into a bit of an event. He has a very loud voice and used it to effect to encourage all of the athletes to work hard! John certainly made an impression on me that day.

At that time my coach, Ronnie Kane had just died and I was looking around for a new coach. Jimmy Campbell got in touch with John and asked if he might take me on.

John lived in Coventry with his wife Dorothy and I used to travel down to stay with them so that I could train with his group, which at that time included Dave Moorcroft, Judy Livermore, Eugene Gilkes, John Graham and the Australian 1500m runner Pat Scammell. I have heard critics of John say he only worked with ‘stars’ who came to him fully formed, but that is nonsense as he worked with many people from when they were young and unknown and also with many club athletes who were never going to become international athletes. However, he expected all of his athletes to be committed to training and to take a professional approach to their athletics whatever their standard. He and Dorothy opened their house to athletes and it was always full of people dropping in for advice or staying over to train. Dorothy is a wonderful lady who went out of her way to look after all of the athletes and make them feel welcome. I was just 18 when I first met Dorothy and being looked after like this when I was away from home meant a lot to me.

With John’s guidance I began to get on track with my training after having lost my way a bit after Ronnie’s death. In my view, John’s training is based around principles of specificity and speed endurance. There is no periodisation in the strictest sense, but training in the winter and competition seasons are different as in the winter the emphasis is on training and in the summer on competition. Typical sessions included 4x600m with 5 mins recovery; 8x300m with 3 mins recovery; 150/300m x6 with the same distance jog recovery; 10x400m and 4x1000m for 5k runners. I also did 10mile runs and ‘stepping stones’: runs which are runs where you run 1mile at, say, 6min per mile followed by a mile at 6.30min per mile for 4 or 6 miles. I also did 20min fast runs.

With this training schedule and the support from the group I made a lot of progress over the winter of 1983. John’s encouragement was a significant factor in this. He was always very positive and encouraging of his athletes and has a great belief in them. My belief in myself did not always match John’s and I guess this was the one difficulty we had in our relationship. But I think that the training system works very well and I based my training around it when I was coaching for a short time with good results.

In 1984 I took around 10 seconds off my pb for 1500m and made the Olympic team. I remember the Olympic Trials in Gateshead well. It was the first time my parents and sister met John. My 18 year old sister did not have a ticket, but this was no problem for John. He liked to play a game with himself involving getting into every stadium he ever visited free. He put his arm round my sister and walked her into the stadium talking intently but every once in a while shouting out hello to passers by. As he expected no one checked whether they had tickets or accreditation because he looked like he was perfectly entitled to walk through the entrance. Alison got one of the best seats in the stand!

John was one of the British team’s coaches in LA, with specific responsibility for multi-events. As a 19 year old it was great to have my coach in the Olympic village with me. One day I went with John and two of the decathletes in the team for a stroll in Venice Beach. Venice attracts a weird and wonderful crowd of people and it was probably one of the few occasions I spent with John where he was one of the least flamboyant characters around!

Mostly, though John was the centre of attention! Gradually all of his athletes got used to this and it was just what they expected of John. I saw this quality being used to great effect though a number of times. One night we were at a charity event part of which involved an auction. The bidding was very sluggish and items were being sold for very small amounts. ‘Watch this’ John said to me getting up and taking over the mike from a timid announcer. In the next 20 mins John got the whole room so enthused that the bids tripled in value. The crowning moment was when he convinced someone to pay £250 for a photograph of two gladiators from the show he was working on at the time! This anecdote highlights some important aspects of John’s character and why he has had such an impact on many athletes and coaches lives: he sees opportunities when others might not, he does not think something is ever a lost cause, he is willing to pull out all of the stops to make things happen and he keeps on going until they do.

John is also fearless. He made much of his upbringing in the tough and mean streets of Glasgow (which was firmly tongue in cheek to those of us actually from Glasgow!) to develop a certain reputation. However I did see this toughness on one occasion when we were on a training camp in Spain. One of the girls in our group came running in and told us there were thieves in one of the athletes’ rooms. John was out of the door faster than Usain Bolt heading to the room which was in another building. He single handedly grabbed the two thieves and held them both against a wall until the police arrived! The police also took John down to the station to investigate this citizen’s arrest as the thieves complained about his treatment! However he was released a short time after and the athletes got all of their stuff back.

I continued to work with John all through the 1980s at the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh and Auckland where he was an England Team coach. I stopped competing for a time in the early 1990s but then in 1995 I decided to start training again more seriously. I had a couple of people who helped me but eventually I got in touch with John again. He was living in Dunfermline and so I was able to see him again regularly. As I was older it was a different sort of relationship. It was more about chatting through ideas. It was great to have John and Dorothy’s support again and to know there were other people I could turn to when I had problems. John helped me train for the 5000m and I had a fairly successful season in 1997.

My track career did not end very well. I dropped out of the AAA’s 5000m and I felt that I was done with running. However, I started to run more on the roads and began to enjoy it again. Once again I went to speak to John about coaching. As I said earlier he does not give up on lost causes and suggested I train for the marathon! Despite having no background in distance running (I had never even done a half marathon) and my not exactly successful career to date he believed I could make the Olympic team!

Training for the marathon involved longer runs, but was still built a lot on ‘speedwork’. For example I did the ‘stepping stones’ sessions – but they were 9 miles long; a common session was 5miles fast/five steady/five fast; track sessions were about 10km in length; long runs were about 15miles to 20miles once a week.

In the end I ran 3 marathons. I did not get the Olympic qualifying time but was selected for the 2002 Commonwealth Games. However, I developed a back injury and could get no-one to treat it effectively. I felt I had lost too much training and gave up my place in the team. I think John was disappointed about this decision as he believed I could have competed. I retired soon after.

I will be ever grateful for the time John gave me and his support over the years. I am glad that through this profile a wider group of people will get to know about and develop a better appreciation of John’s contribution to athletics. ”

Hamish Telfer

Early in his career he coached Hamish Telfer and his friend Cameron McNeish. Cameron went on to become famous as a climber and hill-walker with many books and publications to his name and Hamish became a top class coach in his own right. If you want a review of his career go to

http://www.theleisurereview.co.uk/events/HamishTelfer2.pdf

Hamish sent some of his recollections of his time with John and they are presented below, just as he worded them.

“I understand John was born and brought up in Govanhill, Glasgow. He attended Queens Park Senior Secondary School which was then in Battlefield before its move to Toryglen. I think he may have a sister but I am uncertain. I also understand that he was a fairly competent all-rounder at sport while at school and represented Scottish Schoolboys playing alongside Ally MacLeod. I believe he played centre forward. He may also have played for amateur Scotland. He was also a reasonable gymnast.

He attended the Scottish School of Physical Education at Jordanhill College, Glasgow. I am uncertain as to how many schools he may have taught at, but I certainly remember him telling me he taught at a pretty tough east end school in Glasgow where, to instil some discipline into his charges, he started a gymnastic club which went on to do well at either the full Nationals or the School nationals (possibly winning something). It was at this time in his career that his ambitions coincided with track and field athletics and he got involved as you know with Maryhill Ladies (in all its various early forms). I recall him telling me that in order to realise the ambition of getting to the top of the pile in about 5 years he had a simple dictum. If a parent brought their kid to be coached, they had to do something for the club. John had worked out very early on that he couldn’t get to grips with coaching if he was also the club secy., treasurer, dogsbody etc . He seemed quite ruthless in this demand, as I remember him telling me that there were a number of times that parents took kids elsewhere and he had to watch undoubted talent prosper at other clubs when he would have wished they were with him and his team of coaches. It was around this time that he applied for and got the Scottish National Coach’s job. Maryhill went on to develop and prosper further under the fantastic Jimmy Campbell (as did my own coaching career). [NB: Jimmy had been brought into the sport by John when he was coaching his daughter Mary at Maryhill Ladies AC]

I can’t remember exactly when I first met John but I suspect it was about the time I was 15 (1965). I trained with Cameron McNeish and we were good friends. Cameron was a sprinter long jumper as was I, but he was much better and it was in Cameron that John took an interest. We were members of the now (sadly) defunct West of Scotland Harriers (who also had Ian Walker make it to a Scottish vest at 400 – now a folk singer) and he took over Cameron’s coaching form the coach at the club who was John Todd. In doing so, he also took on me. Much later in my life on one of the occasions when I asked John why he took on a ‘good’ but not really talented athlete, he responded by telling me that apart from the fact that he knew I was a committed athlete (more of that later), he knew that to split up the training partnership could be detrimental to both of us. Cameron and I thus joined John’s ‘National Squad’ at a very tender age. This being the case, I remember John sitting us both down and ‘telling it like it was’ with regards to conduct. If we even sniffed any alcohol (John was, and I think still is, an abstainer), we were out on our ears. Same applied to smoking. We even got lectured about manners and conduct to others, especially women as well as our appearance. We were left somewhat traumatised by the experience but left in no doubt who was boss. I think he did this as he recognised we were very young and he certainly didn’t want anything getting out of hand. Application and hard work also had to be applied to school too.

He was very strong in his views about egos. He encouraged us to believe in ourselves and to feel that there was nothing we couldn’t achieve with hard work and application but he had no truck for big heads (although he did coach David Jenkins which, given David’s ability to appear grandiose on numerous occasions, seemed slightly at odds). He had numerous ways in which he could deflate athletes who believed their own hype and I saw it in action on a number of occasions. I later found out, much to my embarrassment, that my mother, concerned that I was spending considerable amounts of time seemingly with a stranger, sought him out ( I have no idea how) and grilled him. He told me later in life that he could now see the funny side of it but at the time my mother who was a small, slight woman of only 4’10’’, really put him on the spot, especially with regards to training interfering with my school work.

As soon as we joined the squad our training patterns changed under John’s direction. He arranged for us to train with Maryhill Ladies mainly in the winter and I well remember the Friday night sessions at Westbourne School (Madge Carruthers was head of PE there). In addition there were the (mainly winter) sessions at the (newish) Grangemouth Stadium. He also encouraged us to train with the better women sprinters in his charge, and I spent some considerable time training with Avril Beattie and in effect acting as her training partner. She worked in a bank I think, but would get changed at work and meet me near the Queens Park and we would do rep sessions in the park at least once a week in the dark and having to climb over railings to get in and out again. Cameron and I also trained with Anne Wilson (a PE teacher) who was a Scottish International at sprints and LJ. Anne was terrific fun and was the instigator of mischief as well as all of us getting T-shirts bearing the legend ‘Nohj Squad’ (she always addressed John as Nhoj and got away with it). The squad took great pride in its identity and identification with John. Some of the other names I remember were Hugh Baillie, Bob Lawrie, Dunky Middleton, Stuart McCallum, both Jenkins brothers, Lindy Carruthers, Moira Kerr (with whom I did weight training twice weekly at Springburn Sports Centre). There were undoubtedly others but I am uncertain whether they were the core group or simply joined us: Fergus the steeplechaser from Edinburgh Uni, Dougie Edmondson, Lawrie Bryce, McPherson another thrower, Hugh Barrow, Ruth Watt, Adrian thingymabob who was a miler/1500, John Lyle etc etc. My memory needs jogging as to who was around at the time.

John held sessions at Springburn Sports Centre every Tuesday in the winter which was a combination of weights and conditioning. They were hard graft! I remember one occasion when John was called away to the phone at the start of the conditioning session and we wondered what to do as more than 10 mins had elapsed and he hadn’t returned. We decided to carry on (Dunky Middleton was one of the ones in the session so it was a mixture of senior and youth athletes). When John came back 50 mins later we were still going! Knackered but still going. Cameron and I would walk from our schools in the south side of Glasgow to get to these sessions as we only had enough money for a fare one way, so decided to get the bus for the homeward journey. We called in to my Gran’s flat in Springburn often after the session where she would feed us both with bacon and eggs.

John also used Cameron and myself as ‘athlete demonstrators’ on coaching courses both during the week and at weekends and have particular recollections of him picking me up and taking me to Ayr, Inverclyde and various places around Glasgow and Edinburgh. Quite exciting for a young, impressionable athlete. One of the reasons that he was able to do that was he had a firm belief in all-round conditioning for all his young athletes (not the case with the Seniors who he took on). All youngsters in his squad had to master all decathlon events and when the Scottish Schools Easter Athletics Course was under his control, part of the week was dedicated to two days of decathlon competition. This was part of his philosophy that although we start out in one event we may of course end up in another.

Other anecdotes stand out. Cameron and I used to sing in the showers at Grangemouth and this started something of duel between the women in the next changing room who could hear us and the rest of the male squad. It became a standard feature of sessions for a while as to which changing room could outdo the other and John would join in although not so good with the falsetto part in The Righteous Brothers ‘You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling’.

Three other incidents stand out.

-

When Cameron and I were about 18 or so, we bought motorbikes to help us get around to training. This made it easier to get to John’s house too. We often went over to his place at Hamilton to help him splice films for his Specto analyser which he used on coaching courses. This allowed us unparalleled access to his knowledge and to quiz him and to see repeated footage of the likes of Eddy Ottoz going over hurdles. This was without question where I started to chart my career path, as I realised I had a thirst for this and indeed, something of an aptitude. John must have been a bit sick of never being able to get away from us but never complained and his then wife Christine (who was a lovely young woman) must have felt we were like contraceptives. In one particular incident however, I remember going to John’s to get picked up to go to Grangemouth early one Sunday morning. It was in the depths of one the coldest winter spells and it was well under zero in temperature and i was on my small 50cc motorbike. By the time I had got to John’s from south side Glasgow to Hamilton I was more than a bit cold. I got off the bike (just) and made it to his back door and then must have collapsed against the door with hypothermia. I remember nothing until coming round laid flat out in front of the fire in the front room with my head on Christine’s lap. While she was concerned, John wasn’t! He got me up as quick as he could, bundled me into his car (a Volvo after his little VW beetle) and with the heaters in his red Volvo going full blast, we made it to Grangemouth where his only concession was to ‘allow me’ to miss the morning track session substituting it for a 10 mile run (to warm me up again) and then into the afternoon track session.

-

John took Cameron and myself down to Cosford to run indoors when we were about 16 or 17. While I can remember one visit entailed staying at the student halls in Loughborough sleeping on the floor of the rooms of the likes of Mike McKean, Mike Varah and co., I also remember one trip undertaken in dense fog either on the way there or back. On the trip with the freezing fog ……. John asked Cammie and me to get all our clothes on; everything we could put on that we had. Perplexed we obeyed. He then put me in the back with Cammie and then he instructed us to open the windows (one of us on each side) and lean out a bit and give him instructions as to when he might either cross the white line or hit the verge so he could drive a bit faster. I remember these trips usually entailed us getting to John’s the night before to sleep over in order to get up at something like 3am to set off. My life with John always seemed to have theme of ‘cold’.

-

On which note – John was proud of a particularly vicious session he used to inflict on us called 20 second runs. Usually reserved for the Grangemouth sessions, it was indiscriminate in its(his) ability to reduce quality athletes to crawling about the track barfing up what was left in their stomachs. I remember Hugh Baillie being left prostrate on more than one occasion as was Bob Lawrie. The one that sticks in my mind was the session he sprung on us on Christmas Eve one year (which happened to fall on a Sunday, hence Grangemeouth). Thinking we would have one of his fun sessions of a continuous relay with all events involved for fun, he sprung the 20 second run session on us. It was also snowing very heavily. I still have memories of crawling on to the infield after ‘hitting my mark’ and seeing a pair of snow covered feet in front of me and hearing him bark ‘make or not?’ When I responded ‘only just’, he simply bawled, ‘go again’ and moved on to the next victim. We never saw him through the snow in that sheepskin trade mark jacket of his, but we heard him. We were wearing vests and shorts!

Cammie had left athletics by the time he was about 20 as by then he was in the Police Force and the shifts were difficult to fit in and he had also met his future wife and got married at 21. I got a bad injury at PE College and stopped competing in 1970 too. However without a doubt John, for all his faults (and he had many – temper, pig headedness, obstinate, argumentative) was a wonderful influence on me and I owe virtually everything in my career to John’s influence. Indeed it was interesting to hear some people remark that I was a mini version of John when I taught and coached. I would not have had the career I did without John’s help and encouragement.

Later on when I left PE teaching in Scotland in 1975 to take up the post of National Technical Officer (National Coach) for the Royal Life Saving Society, I was then the youngest full time National Coach in any sport in Great Britain. I have since been a GB team coach in Wild Water Canoeing (don’t ask) and also back in my own sport of athletics for cross country. At the top in 3 sports and much of it down to John and his grounding in confidence, learning, knowledge and hard work.

My final ‘memory’ was of the only time John paid me a real complement (this from a man who once described my start from the gun as ‘like watching milk turn’ in terms of ‘response’!) and in true Anderson fashion it came when it mattered; in front of my peers. I was heavily involved in the British Association of National Coaches in the middle part of my career and was one of the ones charged with considering moving the Association forward from its rather elite membership of past and present National Coaches to meet the demands of widening audience of coaches who needed a ‘Coaches Association’ to get their voices heard (we are still waiting!). We invited John as a speaker to our annual conference one year. At this point John and I had not been in contact for some time. We briefly chatted before his session before he went on to talk to the assembled National Coaches from all sports. The talk was about the ‘coach athlete relationship’ or something along those lines. There were just over 100 in the room.

He started his session by saying ‘There is someone in this room who epitomises what a hard working, committed athlete is. Without such athletes, coaches such as yourselves cannot achieve the highest levels of success since talent alone seldom, in my view, is enough without the ability to work hard. That person is Hamish Telfer.’ I can remember it almost verbatim and was quite overwhelmed as I knew it was not in his nature to say things like this. In typical John fashion he had his punch line however. He continued by saying (I suspect in order to lighten the moment) something like … ‘Without a doubt he was the hardest working athlete I have ever coached but unfortunately for Hamish he possessed not a grain of natural talent.’ I still felt quite chuffed but do remember when the laughter died down saying ‘and it’s taken you 20 years to tell me I was crap then Anderson?’

Despite the flaws he inspires fierce loyalty and when I talked to Cameron that is what he remembers too. “

***

Finally, Eric Simpson from Fife paid a wonderful tribute to John and I simply quote it in its entirety.

John Anderson

Everybody in Scotland knows John Anderson, everybody in Britain and many further afield know John Anderson – or knows something about him. John Anderson, along with such as Wilf Paish, Frank Dick and Harry Wilson, is one of the really great British coaches of the twentieth century and probably of all time. Everyone knows about him – coach of athletes who have competed in Commonwealth, European and Olympic Games as well as World championships indoor and out, coach on several GB Olympic teams, fitness trainer and referee on the Gladiators TV programme, coach to famous athletes such as Dave Moorcroft, Judy Livermore, Sheila Carey, John Graham, Liz McColgan, Lynne McDougall and so on. Impossible not to know he is a Scot and a Glaswegian, he is immensely practical, down to earth, immensely knowledgeable and always prepared to share the knowledge with those willing to listen. It was interesting talking to him, reading what I could find and listening to interviews about his career. A brief summary of his career appears in Wikipedia and reads:

Everybody in Scotland knows John Anderson, everybody in Britain and many further afield know John Anderson – or knows something about him. John Anderson, along with such as Wilf Paish, Frank Dick and Harry Wilson, is one of the really great British coaches of the twentieth century and probably of all time. Everyone knows about him – coach of athletes who have competed in Commonwealth, European and Olympic Games as well as World championships indoor and out, coach on several GB Olympic teams, fitness trainer and referee on the Gladiators TV programme, coach to famous athletes such as Dave Moorcroft, Judy Livermore, Sheila Carey, John Graham, Liz McColgan, Lynne McDougall and so on. Impossible not to know he is a Scot and a Glaswegian, he is immensely practical, down to earth, immensely knowledgeable and always prepared to share the knowledge with those willing to listen. It was interesting talking to him, reading what I could find and listening to interviews about his career. A brief summary of his career appears in Wikipedia and reads:

“John Anderson (born 28 November 1932 or 1933) is a former British television personality best known as referee and official trainer on the UK TV show, Gladiators. He has previously worked as a teacher and as a coach for Commonwealth Games and Olympic Games athletes, including Commonwealth Games champion and former World Record Holder David Moorcroft. John was National Coach for the Amateur Athletics Association of England and subsequently the first full time National Coach in Scotland. He was coach to an Olympian at every Olympics from 1964 to 2000 and has coached 5 world record holders and 170 GB Internationals in every event.

In 2008, John briefly resumed his role as referee on the newly revived Gladiators before being replaced by John Coyle after just one series. Anderson went on to become mentor and coach for a number of recent international athletes, including Great British athlete William Sharman, who he helped transform from a decathlete to a world class sprint hurdler, and continues to coach at a local and regional level.”

A very brief entry and, important as Gladiators was, in the context of his athletics coaching, it is not the high point. He tells me he was born in 1931. His fascinating career deserves to be looked at in some detail, from his start in athletics to date. (NB: John only did one series after 2008 because he turned down the renewal because he felt it was changing in a way that he did not approve of.)

*

As a young man, John wanted to teach and was passionate about all kinds of sport. He represented Scotland as a schoolboy footballer. This was in the 1950’s when there was no formal coach education structure available in the country. The only way in to sport as a career was to train as a physical education teacher and there were only two options available to him on that front – Jordanhill College in Scotland or Loughborough in England. Jordanhill College is now of course part of Strathclyde University in Glasgow. John went to Jordanhill and subsequently did a degree at the Open University and went into teaching in Junior Secondary School the east end of Glasgow. Progress as a coach was then down to self study and self motivation – he read voraciously, mainly in the Mitchell Library in Glasgow. He was interested in all sports and went on the FA football coaching course at Loughborough. He did so well that he became the first home Scot to gain the prestigious Full FA Coaching Certificate. It should be noted that at that time only 4 were awarded every year and none had ever been awarded to a ‘home Scot.’ When he came back home with the qualification, football clubs didn’t want to know. There was no desire to use his qualification from those in the sport in Scotland where the clubs all seemed content to do what they had always been doing. He went on teaching and covered such sports as gymnastics and swimming as well as football. He reckons that these helped his future coaching of athletes – all experiences are useful and teach the interested coach, it raised his awareness of the coaching process and taught him how to motivate all kinds of people in different sports, and much more.

He had been a pupil at Queen’s Park Secondary School at the same time as Ally MacLeod. They became firm friends and played together for the Scotland Schools team then when John was National Coach, Ally was manager of the Scottish football team. At a personal level, John was best man when Ally was married.

John only came into athletics by purest chance. He was a member of Victoria Park in the West of Glasgow where he trained for the sprints, but says he really wasn’t much of a runner. Nor was there very much coaching going on at the club – like other clubs at the time there was no proper coach but older and senior members advised the others on what they knew about. Then at school one afternoon the principal PE teacher asked him to take the senior girls for relay practice. There were annual sports for the Junior Secondaries in the area (he taught in Calder Street, St Mark’s JS and Dennistoun JS) and their school was always invited into the meeting. (At that time secondary education in Scotland was divided into Junior and Senior Secondary Schools, with the pupils being segregated at the age of 12) To teach relays, he needed a track and he made a rough track on the ash football field for this team of 14/15 year olds. Came the sports, they won the relay and several other medals: they enjoyed it and he did too but he still thought of himself as a football coach. The girls then asked him if they could carry on with athletics when they left school. He looked around and the only option was Maryhill Harriers Athletic Club and he took them there – the only transport being his own small car. After a few weeks, Tom Williamson at the club asked him to help – after all he was a PE teacher! Then Tom and May Williamson set up their own club, Glasgow Western LAC and John was left with the rump of a club, only half a dozen girls who wanted to keep going. And so Maryhill Ladies AC was set up – you can read about the club and its progress at

http://scottishdistancerunninghistory.co.uk/Maryhill%20Ladies%20AC.htm

Many in Scottish athletics have stories about John at this time – for instance Helen Donald tells of the time she was running in the WAAA’s championships at Crystal Palace and, coming off the last bend in third place was encouraged by John, who was there with his Maryhill athletes, roaring her on and wearing his kilt! Anyway, Maryhill Ladies AC took off and his initial goal of ‘best club in Scotland in three years’ was achieved – use the link and see how well they did.

Never a man to stand still and let inertia govern his conduct as so many do, he contacted his colleagues in other schools and asked them to send along any talented girls that they had and, while they were at it, to send along their parents as well! They were all used and the parents who were helping with the coaching and training of the girls, used to attend classes that he held at his Mum’s house on Sundays He always wanted to know more, and attended a summer school at Loughborough College. In an attempt to test himself, he decided to take all the Senior Coach awards that were available. This was a mammoth undertaking and I cannot imagine any coach doing it today: in fact I have only ever heard of John and Wilf attempting it. He did this – as did Wilf Paish – and then when he heard that new post had been created, that of a peripatetic national coach in England and Wales, he applied. He was given the job and travelled the length and breadth of England and Wales coaching and working with coaches. He even collected some athletes who had no access to coaching or who needed help. This was when there was no national TV, no emails, no mobile phones and communication sometimes took a long time. There was in many clubs no scientific basis for what they were doing – they were doing what their predecessors had done for donkey’s years. He didn’t like that idea. So he started reading again – back to the Mitchell Library, and he wrote to people and sometimes there was a long time for a reply because he was dependent on the postal service.

Then he discovered Geoff Dyson’s book, “The Mechanics Of Athletics” with its scientific approach to the body, information that wouldn’t change , that was scientifically and mathematically based. As he says, his coaching went from being hopeful to being scientific. Later he found Tim Noakes and his work was also assimilated into the training process. Already a voracious reader, he continued to be so despite the increasing levels of success that his athletes had. If he was going to coach somebody then he had to have a scientific basis for what he was going to do or he would not do it. That has not changed – all training has to have a scientific underpinning.

It was at this point that he was asked to do some coaching with the Glasgow High Kelvinside RFC by a rugby friend who was also into athletics. John did some work with them but it was mainly sprints and speed development. The sessions are still remembered by some of those who took part – one chap recalls doing pre-season training on the big pitch at Old Anniesland. Rumour hath it that they disagreed over what constituted a warm-up! The sessions were hard work as Kenny Hamilton, now director of rugby at Glasgow Hawks recalls “3!… 2!…. 1! – I remember him well. A fair amount of resistance-running – possibly the first I experienced which used tyres. I seem to remember a conversation about stretching He was very enthusiastic about stretching muscles – a comparatively foreign concept in rugby circles in those days. He was delivering a talk some place and was asked about how long each stretch should be held for ……. “8 seconds he replied” This then became a bit of a standard but he quietly admitted that there was absolutely no science behind it! However, I can confirm that we were all bloody fit that year, except Cammy!” Cammy Little who was a very good rugby player (he was one of Glasgow’s first contracted players and also played for the Barbarians) says he missed the sessions as it was summer and he played cricket: an old tactic that worked a treat!! John says he was not really a rugby man but it’s funny how these things go around: he is now living near Leicester and since the Chief Exec is a friend he goes along to see the Tigers play and in 2012 even went to Twickenhan to see the Scottish match. He also admits that he has done some work with the Leicester Academy boys and focused on sprinting.

Hugh Barrow and Duncan Middleton training with Cameron McNeish in the foreground

The only thing that he reckons might be queried is whether his interpretation of what their (Dyson and company’s) work had been, was fair. In response to that he can only look at the results of his work with various athletes. With 5 world record holders and 170 GB internationals then there can be a fair assumption that his interpretations have been appropriate. He always measures every coach on the basis of their output. Not if they have only ever had one outstanding athlete – anybody might have an outstanding talent simply by chance – but have there been improvements in all of the athletes that they have coached. John always had talented athletes who came to him who were improved further by his insights and methods. Among those in Scotland to benefit from his coaching were Leslie Watson, Moira Kerr, Duncan Middleton, Graeme Grant, Hugh Barrow, Hamish Telfer (a notable coach in his own right), Craig Douglas, Lindy Carruthers, and the sisters Alix and Jinty Jamieson. The set-up in Glasgow at the time was interesting in that coaches co-operated with each other and Tom Williamson and John worked together on some of the same athletes.

Of the five commonly agreed parameters used to measure an athlete, he feels that Speed is the key. Not who is fastest over 100 metres or whatever, but who has most speed in their event. A marathon runner needs stamina but once he has that then he needs speed for his race distance. This informed everything that he did with his athletes thereafter – if you are in doubt, have a look at some of the sessions noted here and found at the links. If you want to see an example of what John did with John Graham, sub 2:10 marathon man, then look at the profile at http://scottishdistancerunninghistory.co.uk/John%20Graham.htm . Here was a man, John Graham, who had all the stamina required, the move was then to develop the speed necessary to be at the very top of his chosen event. There are also comments on his training methods in the Lynne MacDougall profile at

http://www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.co.uk/Lynne%20McDougall.htm

Graeme Grant

John’s first big national post was as noted above the National Coach in England and then came the post of National Coach in Scotland which he held from 1965 until 1970. Very active, he covered every aspect of the sport in every part of the country. He was the only National Coach that I knew of who even worked with Scottish Schools squad days (the Scottish Schools tend to have their own event coaches for squad days) and was also the man responsible for organising the Annual National Coaching Convention. This was a superb innovation and brought world class coaches from all over the athletics world to speak and talk with Scottish, and indeed British, coaches on their own turf. Every aspect of the sport was covered – technical aspects, fitness and conditioning, physiological testing – and star athletes were often present too. At the end of the conference, all the papers presented were issued to those in attendance in spiral bound booklet form for further study and for dissemination within the clubs across the land. Wherever he was, he was approachable. The coaches were all on side. He also spoke to other conferences and at one he met the Rangers FC manager Jock Wallace. Many years later when Jock was manager at Leicester City FC and John was in Nuneaton, he asked John to come and work with him as a fitness coach. He was also approached for advice by a young player called Gary Lineker. He turned the job offer down but it is one of these intriguing questions – “But what if he hadn’t/”

Then he had the sessions with athletes. For instance the lunchtime sessions at Glasgow University’s ground at Westerlands were legendary with many of the very best in the country training there. The half milers Mike McLean, Graeme Grant and Dick Hodelet were there as was Hugh Barrow from Victoria Park; distance men such as Lachie Stewart were also attendees at the lunchtime training. Runners really went out of their way to attend. The routine, as described by Hugh Barrow, was:

The Mussabini Medal celebrated “the contribution of coaches of UK performers who have achieved outstanding success on the world stage.” Along with the Mussabini Medal, there also existed The Dyson Award, for “individuals who have made a sustained and significant contribution to the development and management of coaching and individual coaches in the UK”. This award was named after Geoff Dyson, the first chief national athletics coach, who died in 1981.

The Mussabini Medal was introduced in conjunction with the launch of the Coaching Hall of Fame. The medal and associated awards were launched to raise the profile of coaches, and increase the financial backing to enhance the profession, still seen at the time as a largely amateur vocation in spite of Mussabini’s pioneering example. Speaking at the inaugural presentation the patron of the Foundation the Princess Royal stated that “Coaching and the work of individual coaches lies at the heart of sport, Yet all too often the role and contribution of the coach remains unrecognised and unacknowledged.”

Quite an honour.

And the script read: ‘One of the Gladiators 6″ Action Figures to collect from the hit show on Sky1. This pack contains John Anderson 6″ action figure with Whistle and Stopwatch. “Contender READY”, “Gladiator READY” are words that can only be uttered by one man. John Anderson is the man behind the whistle, in charge of keeping the Gladiators and contenders in check as well as preparing them for the challenges they face!’

Manufactured by Character Options

What might a Flying Coach visit involve?While it is expected that the focus of the majority of Flying Coach visits will be the technical development of coaches, clubs are encouraged to address other areas of coach development using the Flying Coach scheme, such as:

- Strength & Conditioning

- Fundamental Movement Skills

- Planning and Periodisation

- Communication Skills

- Sport Psychology

Flying Coach Programme: Disability

Wheelchair Racing: An introduction to basic push technique, chair set up and training programmes.

Seated throws: Advice and guidance on seated throws, including throwing frames, tie downs and fixings.

Coaching blind or visually impaired athletes: Advice and guidance on supporting blind or visually impaired athletes, to include guide running and competition pathways.

Coaching deaf or hearing impaired athletes: Advice and guidance on coaching deaf and hearing impaired athletes. To include information on effective communication, technology, Deaf UK Athletics and competition pathways.

Coaching athletes with a learning disability: Advice and guidance on coaching athletes with a learning disability. To include information on Mencap, Special Olympics and competition pathways.

Other impairment specific visits: Advice and guidance on coaching athletes with a specific impairment (Cerebral Palsy, amputees etc). To include information on National Disability Sports Organisations and competition pathways.

So it is not an easy option to follow for the coach – the last section is interesting with our prior knowledge of his work with blind athletes.

John in Cornwall, 2011

In August 2011 for instance he travelled to Cornwall with Tom McNab and Alan Launder to work with the local Cornwall AC for what seems to have been really successful event. There are links at the Cornwall site to two of John’s PowerPoint presentations. The first is called “Most can run, many can race, few win!” and the second is entitled “Preparation/Rehearsal for Sprints”. While they are incomplete without John’s presentation, the headings are enough to make most people think a bit. You can get them at

http://www.cornwallac.org.uk/content/NewsDetails.asp?ID=551

– the links are just below the first picture of the three coaches!

As we said above he is still coaching a small number of top class athletes but he is not yet easing himself into retirement as a coach.

Success at the level he has enjoyed didn’t alter the fact that he was a coach who worked with athletes of all abilities. With his personality and ability he would have been a success in any walk of life: we are fortunate that he chose athletics.

Tributes to John are many but I have some on a separate page which you can reach from this link. Below is the latest photograph we have of John – received in May 2018

There is an excellent article on John on the Playing Pasts website at

Robert Anderson

When it comes to hard working clubmen, Cambuslang’s Robert Anderson has few equals. The living embodiment of the “You do what your club needs you to do” philosophy, he has served as athlete, official, administrator, recruiting sergeant and anything else that required some action. I was told once when I asked where a new club member had come from that Big Robert had signed him up when he was on holiday in the Highlands, and the information was quickly followed by “Don’t laugh, we’ve got three members in Barra from the time he went there!” As a runner he was very good but as Percy Cerutty once said of one of his stars, “He might run faster, but he doesn’t run harder than me.” Robert always ran hard, none of the stars who ran for the club ever ran harder. And yet despite all the stories, he remains friendly and affable – the only time he ever ignores anyone is when Cambuslang is racing and he has a man to shout on. He was profiled in a magazine in the 1980’s but I didn’t recognise the picture painted. The following profile is a tribute to an excellent club man and a lot of help was receibed from Dave Cooney, Cambuslang Harriers team manager for over two decades (and counting!).

Born on 12th February, 1947, Robert joined the club in 1963 at the age of fifteen and has had 50 years in the club. Given what has been said above it might be best to look at his involvement in the various areas in which he has functioned.

AS A RUNNER

It should be noted that Robert worked for many years delivering coal for the family business, even on a Saturday morning before competing later in the day – hardly the ideal preparation. It did however make him stronger than almost all of the opposition. His first individual medal was in 1965 when he was second in the Midland District Youths Cross-Country Championship. The first six were Eddie Knox of Springburn, Robert, Colin Martin of Dumbarton, R Colvin of Springburn, Alistair Johnstone of Victoria Park and Martin Mahon of Shettleston. He was in very good company indeed! He went on in the same season to be ninth in the Youths National. Eddie Knox won that one too with John Fairgrieve (EAC) second and Colin Martin third. Finishing in the top ten was nevertheless a noteworthy achievement with several good runners left behind – eg Alistair Johnston was twelfth n this one. Probably needless to say but he won the Cambuslang Youth championship that year and also won the Junior title. In fact his run of club senior titles took in Senior victories in 1968, ’70, ‘ 71, ’72 and ’73. He continued running in the National – and County and District Championships until the 1990’s and then went on to run in the veterans championships. The 60’s were a good decade for Robert and he also competed on the hills well enough to win the tough Ben Lomond Race 1967 and 1968. On the track he ran 6 Miles in 31:43.0 to be ranked 25th Scot in 1968.

Of course the biggest event for endurance runners in winter, other than the national, was the Edinburgh to Glasgow eight man relay. Robert ran in this for the first time in 1970 when the club ran an incomplete team, turning out on the hard sixth stage. The club missed out in ’71 but were back in ’72 when their twelfth place was good enough to win them the medals for the Most Meritorious unplaced performance. Robert ran on the sixth stage again. He ran on the eighth stage in ’73 pulling the team up one place. Back on the long stage again in ’74, he kept the club in 17th position with another solid run. ’75 saw him again on the sixth stage but in ’76 Robert was on the third stage where he picked up one place. The talk that day was all of John Robson who, when running the third stage stopped altogether and reportedly threw away the baton. No fear of that with Robert who would always do his very best for the club. In ’77 he was again on the final stage for the team which finished eleventh. In ’78 the team finished sixth and Robert was on the seventh leg for a team which was getting stronger all the time with Rod Stone, Colin Donnelly and the Rimmer brothers wearing the colours. ’79 saw the team further strengthened by the addition of Eddie Stewart and improvement to fifth – it was Robert on the seventh stage who picked up from sixth to fifth. Missing ’80, when the team was second, and ’81, he was back on E-G duty in ’82 when the team, minus the Rimmers and Rod Stone but with Eddie Stewart and new man Alex Gilmour formed the backbone, Robert ran the final stage to bring the club home in tenth. That was to be his final run for the club in the Edinburgh to Glasgow but it had a noble stint on behalf of the club.

On the country in the 70’s he was a member of the first Cambuslang team to win a District team medal when they were third in 1976 behind Shettleston and Victoria Park and two years later he won the Lanarkshire County 10 Mile Road Running Championship.

So he was adept at cross-country and road running, then there was track running where in the 1980’s he returned to the Scottish ranking lists for the first time since that 6 miles in 1968. This time it was in the steeplechase where h recorded times of 9:59.1 in 1980, 9:54.1 in ’81 and 9:53.1 in 1982. The ’80’s were in general another good decade for Robert. In 1981 he was a member of the team that took bronze in the Scottish 4 man cross-country championship running first in a team with Lynch, Stone and Stewart. Incidentally the Young Athletes team of Sam Wallace, Pat Morris and David McShane won their race. Becoming a vet in February 1987, he was a member of the Cambuslang team that was second in the Scottish vets cross-country championships in 1988 and again in 1989. Unfortunately from 1990 he suffered increasingly from niggles and injuries that curtailed what running and training he could do. They were beginning to take their toll and although he kept on running an turning out for the club, his last notable race was when he was National M65 cross-country championships in 2013. It was a long career as a runner an he is probably not finished with the vets scene even yet … the latest open race result I have seen is for the Cairnpapple Hill Race in 2012 when he was first M65 and 35th overall.

Robert, third from the left, unusually for him, in the background

Robert, third from the left, unusually for him, in the background

AS A COACH

It used to be a common thing to go to any club on a training night and see older runners standing with a group of younger athletes getting practical advice from his experience. It’s not such a common sight any more and the sport is the poorer for it. Robert was an excellent role model for youngsters – he had run on the road, over the country, up and down the hills and on the track, all with some success. How does he rate as a coach? Well, first and foremost he is dependable. It does not matter if an athlete misses a session, or even two, over the winter. If a coach misses one it is a cardinal sin. Robert would be an ever present. Mike Johnston of course is currently top man and there is a great deal of assistance from Owen Reid and Jim Orr.

His approach is said by a clubmate to be a demanding one but he leads by example. His two maxims are “There is no such thing as pain” and “You can always find time to train if you want to.” The first is maybe a bit overstated but there is no doubt about the truth of the second. Has he been successful? Over the years he has helped to coach and mentor many Scottish individual and team medallists and has contributed greatly to the national success which Cambuslang has enjoyed since 1979 when the Under 13 team won bronze medals in the Scottish Cross-Country Championships. Let’s just list them:

U13 Boys Scottish Cross Country Champions 1992 -96 (runner up by 1 point in 97), 98 – 2000, 2006 and 2013 when his grandson Drew Pollock was a counting member.

U15 Boys Scottish Cross Country Champions 1979, 1992 – 96, 2002, 2005 and 2008.

U17 Boys Scottish Cross Country Champions 1982-85, 1991 -93, 1995 and 96, 2003 and 09.

U20 Boys Scottish Cross Country Champions 1983-85, 1987, 2000, 2002 and 03 and 2013

Senior Men Cross Country Champions 1998 -1995, 1997-2000, 2003 and 2004, 2006 and 2008.

AT Mays Trophy for the Best Male Club at the Scottish Cross Country Championships

Inaugural winners in 1989, 1991- 97, 1999-2006, 2012 and 2013.

Cambuslang has won the trophy on 18 out of 25 occasions.

That is quite a formidable list of medals. Although others did their share of the work, Robert is almost certainly the main driving force.

AS A RECRUITING OFFICER

Robert is famous as a recruiting sergeant for his club. Always on the lookout for new members, he will often just stop runners in the street and ask them if they are interested in joining Cambuslang. Over the years he has been responsible for attracting many new athletes to the club – names such as David Cooney (team manager now for well over a decade), the best known duo in the club of Alex Gilmour and Eddie Stewart, Scottish internationalist Jim Orr who was better than he himself thought he was, hill runner Colin Donnelly, the brothers Joe and Kevin Kealy and Mark McBeth. Involved in the local primary and secondary schools, he was quick to latch on to the new phenomenon of parkruns and now gives out club leaflets at these events held in Glasgow every Saturday morning.

AS A COMMITTEE MEMBER

Inevitably a clubman such as Robert has done more than his share at Committee level and in organising social events, away weekend training expeditions, club relays, Christmas handicaps. He even has a role that not many know about as a GROUNDSMAN, mapping out and maintaining two grass tracks in the summer nights on the rugby pitches at the club since there are no local track facilities available.

Robert on the left at a team mate’s wedding

It was mentioned above that in May 1988 “Scotland’s Runner” published a club profile of Cambuslang Harriers and included in it was a pen portrait of Robert Anderson. This extract says a lot about him.

“He lives, eats, breathes and drinks the sport. As a promising youngster in the club in the 1960’s he would spend a hard morning carrying coal sacks up closes on a Saturday morning, finishing work well after one o’clock, before rushing off to a race at a time when Cambuslang had little hopes of any real success. Like many traditional harriers, he is now suffering the injurious effects of more than 25 years in the sport – many of them spent pounding the pavements in inadequate footwear, something that many youngsters tend to forget in these days of hi-tech footwear.

‘I still manage about 35 miles a week. More than that and I seem to get injured. Who knows, maybe next year … ?’ he says wistfully. But despite the seemingly constant injuries, he has managed a run every day this year.