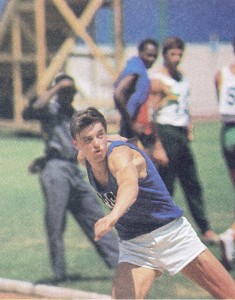

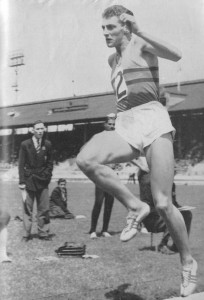

Many coaches, but by no means all, have been competing athletes in their day but even fewer have been national champions or set national records. Tom McNab has been national champion for triple jump five times and also set a national record for the event. He has worked with many top class international athletes and his career has expanded far beyond the usual. A lot of the information has come from his own website, from athletics publications or from people who have worked with him.

Born on 16th December 1933, he was educated at Whitehill Secondary School and then trained as a PE teacher at Jordanhill College in Glasgow. After National Service in the RAF where he reached the rank of Flying Officer he became a Physical Education teacher. He taught from 1958 to 1962 before becoming National Athletics Coach in England. By the age of 18 he had represented Glasgow at football and led the Scottish Senior triple jump rankings and it is as a triple jumper that he was first known in Scotland. He won the SAAA Junior (Under 20) title in 1952, the first year in which it was held, with a distance of 14.01 metres. By SAAA Centenary year of 1982 it had only been surpassed twice – in 1957 when JR Waters cleared 14.07m and in 1976 when I Tomlinson leapt 14.67m. The story behind that success was told by John Keddie in “Scottish Athletics” – the official centenary history of the SAAA. “So slow was British officialdom to promote this event that there was no triple jump in the programme of events of the AAA Junior Championship (instituted in 1931) until 1950, nor in the SAAA Junior championships until two years later. In fact the inaugural SAAA triple jump saw the emergence of an excellent jumper in Thomas McNab. A member of Shettleston Harriers, McNab won the event with forty five feet eleven and three quarters inches, then considered an outstanding performance for a junior athlete. This distance proved to be a foot further than that achieved by the winner of the senior championships held five weeks earlier”.

After that victory, he was awarded the FJ Glegg Memorial Trophy which is awarded annually ‘to the competitor who is adjudged by the General Committee to have accomplished the best performance or performances in the Scottish Junior Championships’ jointly with CM Campbell. In the AAA’s Junior championship at the end of July, he was unlucky to foul his last three jumps and finish fourth – only to see the victor jump the same distance as he himself had cleared at Meadowbank.

Keddie described the triple jump battle between McNab and his clubmate R McG Stephen at the SAAA Championships:

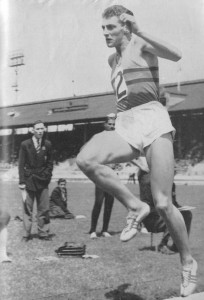

“At the Senior Championships the young Shettleston Harrier had placed third behind a team-mate, Robert McGhie Stephen who had himself been a good Junior having placed second in the AAA Junior triple jump in 1951. He and McNab had a bit of a ding-dong running battle in the SAAA event, Stephen winning in 1953 and 1955, and McNab in 1954 and 1956 (and also winning in 1958 and 1962). Both were in superb form at the 1954 meeting with McNab just out-distancing his colleague 47’7 1/2″ to 47′ 4″. A too strong following wind nullified these performances for record purposes.”

His winning performances were 14.51m in 1954, albeit with the following wind mentioned above, 13.90m in 1956, 14.30m in 1958 and 14.48 metres in 1962.

McNab also had a decathlon points total of 4156 in 1960 which placed him eighth in Scotland, a long jump best of 6.56m and a best discus throw of 36.45 in 1962. He also set a Scottish record in the triple jump of 47’10” (14.58m) in Glasgow in 1958 which was reported in the ‘Glasgow Herald’.

SCOTTISH RECORD AT SCOTSTOUN

Hop, Step and Jump

A new Scottish Hop, Step and Jump record was made in the Victoria Park AAC v Glasgow University athletics match at Scotstoun. Tom McNab (Victoria Park) with a hop, step and jump of 47 feet 10 inches beat by eight inches the record made nine years ago by AS Lindsay.

There was one wee hiccup for him on the way – he was photographed at an unpermitted meeting at Nethybridge in 1956 (he won £5) and barred until late 1957 but it was only a hiccup and nothing more serious. It says more about the SAAA at that time than it says about Tom.

He was probably unlucky not to be selected for any Empire Games – Scotland only sent one triple jumper to the Games in 1954 and in 1958 and none at all in 1950. He would not have been outclassed and his 47’10” in ’58 would have seen him in the top half of the field. He did make the Commonwealth Games in a great year for Scottish Athletics – 1970 – but as a team coach for England.

Tom competed regularly in championships and open meetings and his record in the West District Championships was just as good as in the Nationals with three in four years in 1959, 1960 and 1962 with the one in 1961 being won by John Addo who was Ghanaian. When he won in 1959, the ‘Glasgow Herald report read: “T McNab (Shettleston Harriers) cleared the splendid distance of 48′ 11″ in the hop, step and jump – 1 ft 1 in further than the record he set up at the same meeting a year ago.” But there was no mention of Tom in the 1958 event result as published! At this period too, he was assisting Simon Pearson with the publishing of the Annual Ranking lists – it’s one way of ensuring that your best marks are included, I suppose – but it’s a lot of work and it was pioneering work in the country at the time.

Good as he was as a competitor, McNab is better known as an outstanding coach and writer of technical books. Eric Simpson who came under his spell as a coach says,

“Tom Mc Nab is one of the forgotten heroes of Scottish and British athletics. Like his partner in crime John Anderson he built up an education and coaching expertise that was the envy of the world. Then the professionalism of the sport began and people like Tom were sidelined basically because they were too knowledgeable and they did not suffer fools gladly.

I have great pleasure in seeing Tom every year at the A.A.A.s U20/ u23 Championships and it is always a worthwhile experience. A man of principles and immense knowledge he always gives of his time and expertise and we always have “fun”. A great sense of humour and a biting satire if he needs to. He is one of the dying breed of “great” coaches who inspire and give so much of their time and knowledge to the sport. So much so that the phrase of ” a prophet in his own land is not honoured” jumps to mind – probably the same for John. ”

Maybe Eric’s ‘forgotten’ is exaggerating things a bit but his name is less well known in athletic circles north of the border than it should be. There are some more comments about Tom at the end of this profile by another friend and colleague, Hamish Telfer, another top class coach working south of the border.

He began coaching with Norrie Foster at Shettleston while he was still competing in 1956. Tom had become a PE teacher and says “Even when I was an athlete, I always wanted to find out how I could help other athletes. I remember convincing my club to have pole vault equipment. Once the pole vault equipment was installed the athletics club wanted to know where the pole vaulters were. I tried to explain that just because they had the equipment didn’t mean that they would automatically have pole vaulters. There was a tall skinny child at the club called Norman Foster (below) and I got him to vault. He was a friend and just an ordinary guy who I got into pole vaulting. I coached and trained him. I didn’t know what I was doing it was a bit like the blind leading the blind, however he ended up representing Scotland in the Commonwealth games in Jamaica in 1966.”

Norman was indeed a really topclass talent. His pole vault career is summed up in Keddie’s book. “Norman Foster (23rd July, 1944) eventually developed into one of Britain’s best decathletes, but in 1963 had won the AAA Junior poole vault title with 13’0″ (3.96m). Foster joined the select band of Scottish vaulters to clear 14’6″ (4.42m) when he cleared exactly that height in 1967.” Foster was seventh in the Jamaica Commonwealth Games in 1966 with 13’6″. Keddie also covers Norman’s decathlon career, saying Among the first of a new generation to take up the event was Norman Foster who as a schoolboy at Uddingston Grammar School had his first taste of decathlon in 1961. As an outstanding pole vaulter, he had the physique and mobility to tackle the decathlon. In 1963 he placed third in the SAAA event but the following year won the title with a total (5633) which was recognised as a national record. The same season he was an excellent fourth in the AAA Championship (5752) but it was in 1965 that Foster made a real breakthrough. “

A real class act, Foster totalled 6763 in the SAAA Decathlon (new points table) and in a nail biting AAA’s championship he won with 6840 – a UK record. Injury seriously affected his competition although he was third in the AAA’s twice and won the SAAA event three times.

Coaching was difficult after Tom moved south but the link was maintained for a period although the friendship has lasted for over half a century – Norrie and his wife went to the Pitlochry Theatre to see him when his wife, Jenny Lee, was acting in ‘The Steamie’ at the end of 2013.

Coaching progress thereafter was rapid. Hugh Barrow won the AAA Junior Mile title in 1963 and was also awarded the trophy for the best athlete in the meeting. The trophy was presented to him by Tom McNab who had been invited up from England to lecture to coaches at Strathclyde University. Tom had by this time in 1963 become National Athletics Coach for England: a post he was to hold for almost 15 years. Almost immediately he had a high degree of success with the English Triple Jumper Fred Alsop who was fourth in the 1964 Olympic Games. Alsop cleared 16.46 metres and his fourth place was eight higher than his performance in the 1960 Games. Alsop was of course only the first of many. Another who had great success in an event that Tom himself had taken part in was Peter Gabbet. A good athlete from the start, the notable decathlete worked with Tom after he took up the event and the entry in Wikipedia says

In a 1971 interview with Dave Cocksedge, asked when he first got hooked on the decathlon, Gabbet said, “It was training under Tom McNab and getting inspired by him that helped the most. I began to see the possibilities for myself; realised I had a good top class decathlon in me if I worked hard enough for it.” Four decathlons in 1967 confirmed Gabbett’s work ethic and enthusiasm. In May he competed twice in two weeks showing some improvement in the technical events if not the total score. In July he won the AAA Championship at Hurlingham (11.1 6.63 11.75 1.80 50.2 16.3 36.64 3.00 44.92 4:40.4) with a new personal best score of 6,533 points, and in September he went to Liege in Belgium for his first international meet where he further improved his best in finishing fourth (11.0 7.10 9.27 1.83 49.7 16.2 34.14 3.00 48.62 4:36.2) with 6,562 points.

1968 was an Olympic year, so the target for Gabbett and McNab as they headed into winter training is the Olympic qualifying mark of 7,200 points, the race for which turned into something of an adventure. Indoor marks of 7.1s for 60 metres and 8.6s for 60 metre hurdles are hardly sparkling by the standard of specialist sprinters, but were a new direction for UK decathletes. The outdoor season kicked off with an encouraging 7.20m long jump at Oxford in March, after which Gabbett suffered a stress-fracture in his foot. Then in July he went to Crystal Palace for his first decathlon of the season. A 10.8s 100m and a fine 7.35m long jump set up the first day nicely, and after a “fiery” 48.7s 400m in which he “demolished” 400 metre specialist John Hemery, Gabbett ended day one on 3,901 points, easily the best by a British athlete. Below par for the first two events on the next day, both Jim Smith and Dave Travis the javelin specialist closed in on Gabbett, but a determined personal best 3.40m in the pole vault put him not just back in the lead but back on schedule. A “pathetic” javelin throw of 42.91m ended hopes of achieving the Olympic qualifying mark, but all three leaders had hopes of achieving 7,000 points as they lined up for the final event. Travis tried gallantly but could not stay with the nimbler athlete and Gabbett’s 5.7s lead at the tape was sufficient for his first National Record (10.8 7.35 11.78 1.83 48.7 15.7 35.91 3.40 42.91 4:25.2) of 7,082 points. Travis also passed 7,000 points and third placed Jim Smith was only 22 points shy of the mark. With two decathletes over 7,000 points, respected athletics journalist Mel Watman said that British decathlon had, “come of age”.

For the rest of the article go to the Wiki entry for Peter Gabbet at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Gabbett .

Like all good men in any walk of life, Tom was never still. While working as hard as any National Coach he still found time to write and organise. His fertile imagination came up with two schemes almost immediately after he went south. In 1966 he created a National Junior Decathlon Programme, one of the products of which was Daley Thomson. He also created the Five Star Awards as an incentive scheme for children in schools and clubs. It was a wonderful scheme – Frank Dick subsequently created a similar scheme in Scotland known as the Thistle Awards. Those taking part were required to do both track and field events with certificates and badges in various colours to indicate the level of achievement. Participants could win multiple awards and it was usual to see track suits smothered with the badges at championship meetings. It was a pity when the scheme was discontinued some decades later – but it was so highly thought of that several clubs continue to use the scoring tables with only slight modification for club awards. Later in his career he devised the Ten Step Award, sponsored in Scotland by IBM, for Under 12’s.

He also did a lot of writing in 1966 – his excellent book ‘Modern Schools Athletics’ became a standard text for coaches at school and at club level. It was very good and I had just bought a copy when I travelled to Gourock Highland Games and it was nicked from the dressing-room while I was competing! He also had two coaching manuals for the AAA series of instructional booklets on Triple Jump and Decathlon. He went on to write many, many books on training technique such as ‘Roots of Training Technique’. By 1968 he had written with his friend Peter Lovesey the first ever British athletics bibliography with over 1000 books included therein. One year later he won a Churchill Scholarship to go to the USA to study American athletics literature. It was in 1968 too that he and Tony Ward travelled to Poland to see how their athletic league worked before the British National Athletic League was formed.

There were many, many articles for Athletics Weekly and other athletics and coaching magazines over the years as well as lecturing, talking to groups large and small and he was one of the best ever, hands-on, British coaches. This was recognised in 2001 when he received the Dyson Award. This is awarded to “individuals who have made a sustained and significant contribution to the development and management of coaching and individual coaches in the UK”. This award was named after Geoff Dyson, the first chief national athletics coach, who died in 1981. He is one of only three GB coaches to have gained this award, the others being Maeve Kyle and Frank Dick. This sat nicely with the Winston Churchill Fellowship award that he had received in 1967.

A prolific writer, the www.goodreads.com website lists many of his books – Field Events by Tom McNab; Modern Schools Athletics by Tom McNab; Speed by Tom McNab; The Complete Book of Track & Field by Tom McNab; Blooms of Dublin by Tom McNab; The Complete Book of Athletics by Tom McNab; An Athletics Compendium by Tom McNab; Combined Events by David Lease and Tom McNab; The Guide to British Track and Field Literature by Peter Lovesey and Tom McNab + the fiction noted below.

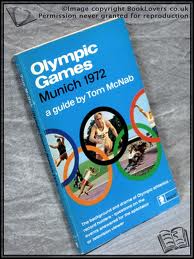

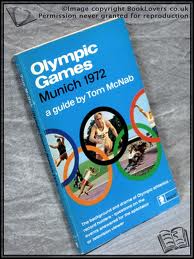

Although listed on the Dyson Awards as ‘Tom McNab, Athletics’ he is not a one sport man. If we just look at his career this is clearly the case. The National Athletics Coach post lasted from 1963 to 1977. He was of course an Olympic Coach between 1972 and 1976. As early as 1970, he was working with the Chelsea FC team that won the FA Cup. There was a year in Dubai in 1977 before being approached by the British Bobsleigh Association to prepare the 1980 Lake Placid Olympic team. The aim was to improve the team’s starting-times and Tom transformed training-methods and brought athletes into the squad. This resulted in Great Britain becoming 5th fastest starters in Lake Placid, a massive improvement. What was next? Director of Sport at TV-AM is what was next. In 1983-4 he worked with Peter Jay, Michael Parkinson and David Frost to bring into being ‘TV-am’, Britain’s first commercial breakfast television station. He then became Fitness Advisor to the Rugby Football Union between 1987 and 1992 which included working with the English rugby team that was second in the 1992 Rugby World Cup. He was co-author with Rex Hazeldine of ‘The RFU Guide to Fitness for Rugby’ in 1998. In 1997, he was appointed Performance Director to the British Bobsleigh Association.

This all suggests that he was finished with athletics – far from it. In 1990 he moved back into athletics and formed a three hundred member athletics club in his home town, St. Albans. For more information on this one have a look at http://www.stalbans-athletics.org.uk/history.html In 1992, and 1994, he was a British Coach of the Year. In 1993 he returned to competitive athletics in hammer at the age of sixty, winning medals at national level. Came the millennium and Tom was back into athletics coaching with a vengeance, and from 2005 working for a while with Greg Rutherford whom he helped become the best Junior Long Jumper in the world. He was at the same time a World Class adviser for UK Sport and in 2004 wrote the McNab Report on English amateur boxing. This was implemented and helped lead to British boxing’s most successful Olympics ever in 2008. In 2011, together with Alan Launder and John Anderson, he took part in a ‘Coaching Legends’ weekend in Cornwall which was a great success. He is currently listed on the Power of 10 website as coaching a group of six young London athletes – John Otugade of Shaftesbury Barnet (U20 sprinter), Teepee Princewill of Harrow (U15 TJ), and four from Enfield & Haringey – Lawrence Davis (U20 TJ), Ibitoye Ibikunle (U20 TJ), Bradley Pike (U23) and Efe Uwaifo (U20 TJ). All are highly ranked but you can look them up on www.powerof10.info .

Hamish Telfer, yet another Scot who worked as a national coach in England, met and worked with Tom. Like Eric, Norrie and others the friendship still maintains. He has this to say.

“Although I knew about Tom I didn’t meet him until I became a National Coach in 1976 (I worked as the National Officer for the Royal Life Saving Society for 3 years). He introduced himself to me at a the annual conference of BANC (British Association of National Coaches) of which I was a member. He discovered I had been coached by John and as a very young National Coach he took me under his wing a bit (I was the youngest National Coach in any sport at that time). We chatted on and off, but lost touch a bit until UK Sport through its ‘education’ arm Sportscoach UK decided in the wake of BANC opening its doors to all coaches and then merging its interests with Sportscoach UK (SCUK), to open its doors more widely to be a voice of all coaches. Tom and myself were voted on to the main committee by our peers to speak on ‘things coaching’ and in effect to get a professional association for coaches off the ground. Anderson was voted in as chair. This was a pretty high level group involving many good quality coaches from across a range of sports (eg. John Shedden from skiing, Hugh Mantle for canoe slalom, John Lyle etc etc.); a broad church but all with mutual respect for each other.

It was a disaster from the start. It was clear that SCUK had an agenda. To cut a long story short, the coaches association crashed and burned and although Tom like the rest of us did his best, there is now no organisation in the UK that speaks for coaches. I can’t recall when Tom left British Athletics, but he went on to advise the British Bobsled team for a winter Olympics (or two) and also had a hand in conditioning some of the better rugby union teams of the day.

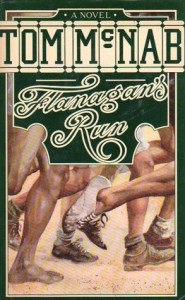

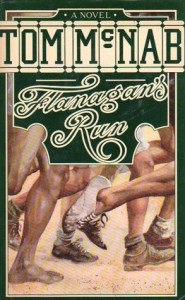

Parallel to all this was Tom’s then embryonic interest in writing. He published a series of novels as I’m sure you know including ‘Flanigan’s Run’ (for which he sold the film rights). He was probably better known for his work on the film ‘Chariots of Fire’ based on his (almost) encyclopaedic knowledge of the history of track and field athletics especially the old Peds., their trainers and training methods. Some of this was filmed at Bebbington Oval on the Wirral and some of my athletes were extras, including one poor sod who had to fall in a race (cinder track) so was greased up so the cinders didn’t graze him too much. Sadly, there was more than one take of the scene and he came out of it with yards of skin missing from his arms and legs. Not a good look!

Latterly Tom has taken to writing for radio and for theatre both of which he has enjoyed some success. Not all of his work in these mediums have been to do with sport, but I went down to see his theatre production of Jesse Owens and the Berlin Games in London in 2012 and we met up over a coffee. It was a bit disconcerting sitting next to Goebels however.

Apart from that we phone each other intermittently when we don’t bump into each other in Sauchiehall Street (when he roundly abused me for cycling Lands End to John o’ Groats). “

Tom is also very well known for his career away from the sports arena – as technical director for the film ‘Chariots of Fire’ and for the three top class books – ‘Flanagan’s Run’, 1982,about the trans-continental footrace, ‘Rings of Sand’, 1984, ‘The Fast Men’, 1986, described as the first sports-western novel. The film was excellent and as technical director he was responsible for making the visual aspects of the athletics training and racing as realistic as possible – teaching actors to look like runners, showing sprint drills and races to best effect and generally add to the film rather than these sections being the boring bits of the movie as could so easily have been the case. ‘Flanagan’s Run’ was my own favourite, probably because I had been given a couple of Arthur Newton’s books and had read about the races across America beforehand. I don’t think I was alone because it was translated into at least 16 languages and Tom won the Scottish Novelist of the Year Award. There were also several radio plays including ‘The Great Bunion Derby’ and ‘Winning’ which featured Brian Cox.

He was still involved in athletics of course – in 1976 he had become an official IOC historian and contributed to Lord Killanin’s book called ‘The Olympic Games’ and in 2002, in collaboration with Andrew Huxtable and Peter Lovesey, he produced for the British Library The Compendium Of Athletics Literature, a scholarly work covering over 1300 books on athletics. As a freelance journalist his work has appeared in The Independent, the Times, the Observer and the Telegraph.

Tom takes a full part in activities in St Alban’s where he now lives – an article in his local paper said:

“Impressively active at 77, Tom limits his coaching to young players nowadays. But he won national hammer titles at 60 and was still playing rugby for Old Albanians veterans at 66. Today hes a regular visitor to the Nuffield Health gym in Highfield Park Drive and plays twice a week at Townsend Tennis Club in the Oldies section run by Alison Asplin, another of those dedicated volunteers.” (Tom had only taken up tennis at the age of 46, and says “It’s not about the age, it’s about levels of energy. I was a late developer in most ways – when you are older you have a background of effective thought. There is no point in having past experiences whilst you are here if they don’t have an impact on the way you act. You stop growing when you stop thinking.” )

Having seen his last play – “1936″ – about the Berlin Olympics fill theatres in the West End in 2012 Tom is already working on his next project.

After a competitive career that would have filled any reasonable athlete with some pride, Tom went on to become an award winning coach in several sports, had a successful career as coach and writer of technical manuals, as a novelist and playwright and currently working on a novel of his play ‘1936′ and on a campaign to bring back Village Sports to the nation.

I would suggest looking up some of his articles online – maybe start with the one quoted above about his start in coaching at http://phenomenalhealthstyle.tv/2012/09/30/conscious-coaching-olympic-coach-and-playwright-tom-mcnab-share-his-olympic-life-lessons-from-sports/#.UvOXqvl_vxQ

Or one on stretching from AW republished by the West of Scotland Sprint Squad at

https://sites.google.com/site/vpcogsprint/news/lessismorebytommcnab

or maybe the thought provoking one which he wrote for Peak Performance which can be found at

http://www.pponline.co.uk/encyc/sports-coaching-coaches-should-rely-more-on-sport-science-than-sports-trends-40813

or better still look at this one from 2012

http://www.pponline.co.uk/encyc/olympics-legacy-london-2012-1093

There are lots of examples of his writing on the internet including some remarks on bee pollen from the 1970’s, comments on the training of Captain Barclay as well as many technical and non-technical ones on all aspects of the sport. Look them up, read what the man has to say!