Author: Admin

Paddy Cannon

Paddy Cannon

The article below is a fascinating account of the life and sporting career of Paddy Cannon, written by Alex Wilson who donated it to us and published in the Track Stats magazine. Alex has taken a lot of trouble to research the subject and he is the only one from that particular period on this website. It not only tells us a lot about the man himself but also illustrates and describes an athletics scene that is different from our own but which at its heart is basically the same.

The Career of Paddy Cannon, farm worker, record breaking professional runner, successful football trainer.

By Alex Wilson

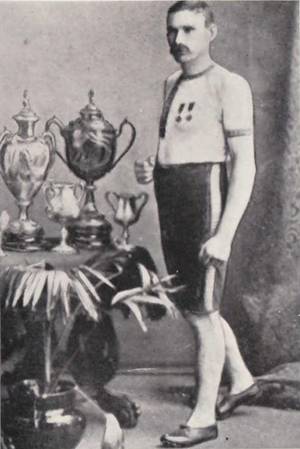

The name of Paddy Cannon, alias Peter Cannon, will not be familiar to many today, but in his time he was a very popular figure in his native Scotland and even further afield. During the 89 years of his life, he created what you might call an enduring legacy by leaving his indelible imprint in the history books, both as a distance runners and as a football coach. Cannon was of medium build, stood 5’8″ (173cm) and never weighed more than 147lbs (67kg) during his competitive days. But behind the moustache and unassuming demeanour lurked a ferocious competitor with a burning desire to win – whatever the sport. In addition to setting two professional world records on the running track, he coached Edinburgh side Hibernian to their last win in the Scottish Cup.

Paddy Cannon first saw the light of day at Raploch, near Stirling, on 14th January 1857, the son of Irish immigrants Peter and Bridget Cannon. His father was an agricultural labourer who worked on King’s Park Farm. In those days the farm occupied a sprawling piece of land beneath the craggy outcrop on which Stirling Castle stands. Today, it’s a golf course. From an early age he learned to pull his weight on the farm. Just like any other youth, he played football and enjoyed sports, but never did he imagine that he would make history on the running track and set two world records. In fact, he was 20 years of age before he realised that he had any talent for running. It was by mere chance that Paddy Cannon became a runner.

The story has it that in 1877 a Glasgow shoemaker who had settled in Stirling noticed a group of young men in King’s Park. The shoemaker had been an athletics trainer and, seeking to carve out a new niche for himself in Stirling, persuaded the men to show their paces. One of these was Paddy Cannon, who, despite being dressed in heavy workboots and corduroys, romped home an easy winner. The shoemaker was so impressed with what he saw that he arranged for another trial a short time later. On this occasion he brought along a pair of running shoes for Cannon who, now properly attired, showed his true ability. Excited by his discovery, the shoemaker became Cannon’s sponsor and two weeks after the second tryout persuaded Cannon to enter the Strathallan Games at Bridge of Allan. He ran in the open mile off the 100 yards mark. there was a huge field but Cannon held his own and but for inexperience would have won. He was only beaten by a foot and a half into third place behind David Livingstone of Tranent, himself on the cusp of a successful career. On May 31st 1881, Livingstone would finish second in 53:53.5 to William Cummings in the prestigious “Ten Miles Race for Sir John Astley’s Champion Belt” at Lillie Bridge Grounds, West Brompton. Cannon’s rookie performance created quite a stir among the local pedestrians. A week later at Falkirk, he avenged his Strathallan defeat by winning the confined mile for Stirlingshire men, the open mile and the two and three mile handicaps! This was an extraordinary performance for a novice. Paddy Cannon would not have been a runner had it not been for the Scottish Highland Games, a millennium old tradition which had enjoyed something of a revival in Scotland with the advent of half-day working on Saturdays and statutory bank holidays. By the late 1870’s they were a common and highly popular Saturday afternoon pastime. He was practically invincible in two and three mile races at Highland meetings where he would concede all manner of starts to his opponents and still come out on top Unfortunately, promoters were rarely particular about track measurement or timekeeping. All that essentially mattered was finishing order, as this dictated the distribution of prize monies. many of Cannon’s performances no doubt some very good ones, are therefore unknown. Not much is known about Cannon’s early career, save that he is said to have run the great William Cummings of Paisley, then world record holder for the mile, to within a yard in the Bute Highland Games in the early 1880’s.

In 1883, Cannon renewed his rivalry with David Livingston in the Five Miles Championship of Scotland at Arbroath on 15th September. In a close-run race he finished a yard behind the Tranent runner who was credited with a time of 24L31.0. It would have been a world record had the track withstood scrutiny.

Back on the Farm and hard Work to keep Fit

After his early successes, Cannon went back to working on the farm with occasional spells at the saw-mills during the winter, and when the summer came round, he would free himself for the Highland Games season. However the farm work, as Cannon knew, was hard graft without labour saving mechanisation. Stacking hay, to mention but one example, was an intensely physical chore before the advent of hay baling machines. This was one reason why Cannon was extremely fit despite doing little in the way of specific training. In fact he was a great believer in the benefits of walking and hard work. By his own admission he was a hard taskmaster, as demanding of himself as of others, a sentiment echoed by John James Miller in “Scottish Sports and How to Excel in them: a Handbook for Beginners”: “Punishment”, vowed Paddy Cannon to me on one occasion, “that’s the keynote for distance running efficiency. That is the mill I had to go through and there’s absolutely no other way.” Unusually fro the time, Cannon neither drunk nor smoked. His physical fitness and healthy lifestyle no doubt enabled him to withstand the rigours of weekly competition during the summer Highland Games season. He usually ran in two events, and sometimes in three, at meetings, racking up the racing miles. He clearly showed a preference for meetings which promoted both one and two mile events where he could make double money. In 1885, having been practically unbeatable in Scotland over two miles, Cannon turned his attention further afield. Pedestrianism was flourishing in Lancashire and Cannon’s sponsors entered him for what was a famous four-mile handicap promoted by Albert Fletcher at the Moorfield Recreation Grounds in Failsworth, near Manchester. The “All England Sweepstakes” were held on 19th September 1885 and featured a quality field including Arthur Norris of Brentwood and William Cummings, lately of Preston. Cannon was comparatively unknown in these parts and Cummings was handicapped by 200 yards. Cannon’s backers couldn’t believe their luck and betted heavily on their man at odds of 4 – 1 against. The outcome was almost a foregone conclusion: Cannon overhauled the last of the runners to whom he had conceded starts at the halfway mark. Taking the lead before the three mile mark (c14:40), he ran out an easy winner in 19:28.0 (equivalent to a shade over 20 minutes for the full four miles.) The backmarkers didn’t stand a chance, and Cummings pulled out early in the race after failing to make any inroads on Cannon’s lead. Needless to say, Cannon’s jubilant backers went home with a sackful of money. However, in his defence, Cummings was likely saving himself for an upcoming race at Lillie Bridge that would decide a high-stakes three-race match against Walter George, the ex-amateur champion from Worcester. If so, the strategy certainly paid off, Cummings easily defeating George by 420 yards in a world record time of 51:06.6 amid claims that George had been poisoned.

Cummings and Cannon seem to have struck up a working relationship after crossing paths at the Failsworth meeting. A little over a week after Failsworth, Cannon accompanied Cummings to Lillie Bridge for his race against Walter George. On 3rd October both men appeared in the Mile Handicap at the Edinburgh Royal Gymnasium. The reporting newspaper noted that Cannon had been “training along with the Scottish champion Cummings.” The working partnership continued in 1886 when Cannon trained Cummings at Preston in preparation for another series of matches against Walter George over a mile, four miles and ten miles for £200 each. The first match in the series, a Mile race at Lillie Bridge on 1st August culminated in a victory for George in a phenomenal 4:12 and three quarters – over three seconds below the previous world record held by Cummings, who collapsed (gave up) 100 yards from home. Cummings levelled the scores by winning, albeit with suspicious ease, the second race over four miles at Preston Pleasure Gardens in 20:12.6 on 11th September, thereby forcing a lucrative decider at Aston Lower Ground, Birmingham, on 2nd October. This time George had his revenge, setting a hot pave with the avowed intention of running his opponent off his legs. Indeed he succeeded in breaking Cummings in the third mile, which can be explained by the fact that the first three miles were accomplished in a near-world-record 14:40.2. Cummings fell increasingly further behind and eventually retired in the sixth mile, having been lapped. George reached six miles in 30:26.8 but without any opposition to spur him on, slowed thereafter to outside world record pace and was eventually allowed to stop in the ninth mile. That concluded Cannon’s working partnership with Cummings, even if the consensus was that Walter George was unbeatable. Cannon had by all accounts done a good job of nursing Cummings through injury and back to peak fitness. In his mile race against George, Cummings after all had led at the three quarter mile mark in a near-record 3:07 and three quarters, and would probably have beaten his own best time had he finished.

With the matches out of the way, Paddy Cannon and William Cummings went back to being adversaries. Apart from coaching Cummings, 1886 was a relatively quiet year for Cannon. He did, however, seize the opportunity to visit his ancestral homeland turning out in the half mile and mile handicaps at the Caledonian Games at the Ball’s Bridge Ground, Dublin, on 13th June. He was npt in his best form however, and lost both events, coming in third in the half mile in 2:09.5 and second in the mile in 4:41.3. On to the 1887 season which Cannon began with a bang, winning the two mile handicap at the Broxburn Annual Athletic Games on July 14th, in 9:21.0 – a Scottish professional record and one of the fastest times to date. Nine days later, he showed a good turn of speed in the mile handicap at the Edinburgh Royal Gymnasium finishing third off 50 yards in an estimated 4:21.0. On 8th September 1887, Cannon dispelled any doubts that there might have been over his performance in the

two miles at Broxburn by winning the two mile handicap at the Manchester Royal Jubilee Exhibition Sports, held to commemorate 50 years of Queen Victoria’s reign. After rushing through the first mile in 4:33.0, the Stirling runner came home in 9:21.5, defeating fellow Scot Joe Newton of Dundee by 150 yards. Also in September, 1887, and probably in connection with his appearance at the Manchester Exhibition, Cannon competed in the ix Miles Handicap at Failsworth – the scene of his four miles coup two years before. The field included Will Snook, of Shrewsbury, the former Birchfield Harrier who, as an amateur, was a two-time AAA 10 Miles Champion and two mile world record holder. In 1886 Snook had been suspended by the Amateur Athletic Association on allegations of roping (not trying to win) un the National Cross Country Championships and banished to the professional ranks. Snook had recently won a mile race at Leicester in 4:27.8 and so was still a force to be reckoned with . Details are sparse, save that Cannon was placed at the 110 yards mark and won in 30:46.2 (worth 25:54.7 for five miles), beating Snook by 400 yards.

Three months later Cannon returned to Failsworth Ground to race Arthur Norris of Brentwood in a mile race for a £50 cup and £50. Norris, a 4:36 miler, had unexpectedly defeated Cummings the previous year and needed only to win to make the cup his absolute property. He received 40 yards start, thus presenting Cannon with a stiff task. A crowd of fully 1000 persons watched anxiously as cannon went off at a great pace and caught his man at half way, but he couldn’t break Norris and in the home straight the Brentwood man drew right away to win by eight yards in 4:31.5. In Cannon’s defence, the Failsworth race came only three weeks after marrying a 22 year old weaver called Annie Mackin at St Mary’s Chapel in Stirling.

Cannon set about preparing for the 1888 season with a new found zeal and strength of purpose his self-professed ambition to set up a professional record for the two miles or any other distance. Having broken with his previous summer/winter cycle by running at Failsworth in late 1887, Cannon entered the Professional Mile Championship at the recently opened Victoria Park Grounds, Govan, on 21st January 1888. There were three competitors: himself, William Cummings of Preston and Arthur Norris of Brentwood. The match was for a sweepstakes of £25-a-side and a challenge cup. The 50 guinea solid silver cup had been presented by Mr Lewis, a London patron of pedestrianism, and had to be held against all-comers for 18 months.

Defeat by William Cummings for the Mile Championship

Despite the unfavourable weather and a heavy track due to rainfall on the morning of the race, some 3000 persons assembled to witness the event. Cummings was the favourite at 6 to 4, while odds of 3 to 1 were being offered against Norris and 4 to 1 against Cannon. Norris received 40 yards start, Cummings and Cannon starting from scratch. Cannon reeled off the first quarter in 62 seconds with Cummings, playing his usual waiting game, on his shoulder. At the end of the first lap, Norris still had his handicap having set off at an equally hot pace. In the second lap, the scratch men pegged back 20 yards on Norris and the half mile was reached in 2:09.5. Cummings went past Cannon in the third lap and was within 10 yards of Norris when the three-quarter mile post was reached in 3:16.0. Cummings rushed past Norris on the last lap and sailed up the straight, looking back the easiest of winners by 10 yards in 428.0. Cannon was second in an estimated 4:30.0, a similar distance in front of Norris. In February 1888, there was talk of a series of races against William Cummings at two miles, four miles and six miles, each race worth £25 a side. However, the proposed match fell through, as these kinds of tentative arrangements so often did. On 14th May 1888, Cannon entered into a three mile match with Robert Hunter of Govan at the Victoria Park Grounds, Govan, conceding Hunter a start of 350 yards. Nine days earlier, Hunter had run a dead-heat with Cannon in another three mile handicap at teh Vale of Clyde AC sports having received 350 yards start there too. A close race was again expected though Cannon was still the bookies’ favourite at 6 – 4 on. The Stirling man went away at such a fast pace that everyone expected him to crack. However he was in fine fettle and the track was in good condition. Hunter was overhauled three quarters a mile from home and retired with a lap to go. Never slackening his pace, Cannon plugged away and broke the tape amid thunderous applause, to find that he had written his name into the record books. His time of 14:19.5 was fully 16 seconds inside Jack White’s record. From now on, Peter Cannon would be named in the same breath as Walter George and William Cummings. Cannon now turned his attention to the two miles record.

The opportunity arose out of a three-way two-mile sweepstake involving himself, Walter George and William Cummings. Cummings however was forced to withdraw at the eleventh hour owing to a leg injury. On Saturday, July 28th, 1888, in heavy rain, Cannon finally crossed swords with the great Walter George at the Victoria Park Grounds in Govan. A close race was anticipated, and given the constellation, a world record was definitely in the air. Of the two men, George had the faster time, having run 9:17.4 at Stamford Bridge in 1884, but Cannon was the man in form. Despite the weather, some 3000 spectators turned out to witness the race. The track was rough and heavy, and a record looked impossible, but the Stirling man was undeterred. The toss fell to George and he took the inside lane, but shortly after the start, Cannon went to the front and soon left his illustrious opponent far behind. He was 150 yards ahead at the end of the first mile in 4:33.4, his powerful stride eating up the ground. Maintaining an electrifying pace, Cannon won easily by 300 yards and brought the house down with a comprehensive victory. The official timekeeper, Mr Bonar registered 9:12.5 on his watch. Cannon had therefore missed Bill “Crowcatcher” Lang’s long-standing record by a mere second. But for a better surface and someone to push him, as James Sanderson had done Bill Lang at Manchester 25 years earlier, the record would have been his. In return for his efforts, Cannon carried off a mammoth money prize of £300, which surely would have made up for any disappointment he felt at missing the record. That year, Cannon made another attempt to break the two miles record at the Glasgow Exhibition enclosure on September 8th. His race was the highlight of an excellent afternoon of sports at the “Highland Gathering” and witnessed by a bumper crowd of upwards of 25,000 spectators. With a number of runners starting ahead of him, Cannon made his usual fast start, passing the mile post in a blistering 4:32:0 However this effort was too much to sustain; he faded in the closing stages and was left licking his wounds in second place. Ferguson of Greenock took full advantage of 140 yards start to win a “punishing” race by a good 10 yards in 9:22.4 to Cannon’s estimated 9:25.0.

An attempt on the four mile record and a crowd of 10000 to spur him on

Cannon returned to the Glasgow Exhibition and made his next record attempt in a Four Miles Handicap on Saturday November 3rd 1888. The world’s best was 19:36.0, accomplished by Jack White, the legendary “Gateshead Clipper” at Hackney Wick on 11th May, 1863. The weather was raw and uninviting, and not conducive to record breaking but nevertheless a large crowd turned out to watch the professional sports and, in particular, to see Paddy Cannon run. Eight started, the Stirling man the back marker off scratch and conceding big starts to veterans William “Cutty” Smith of Paisley, and Bob Hunter of Govan. The task looked impossible for when the men stood on their marks, Smith and Hunter were only 40 yards behind Paddy, with practically a lap in hand. Nonetheless, Cannon immediately set about pegging back their lead, passing the mile post in 4:48.2, 2 miles in 9:44.0 and 3 miles in 14:45.0. Entering the last half mile he was only 50 yards down on the leaders, Hunter and Smith and closing rapidly. In the last lap he finally took the lead but despite a spirited sprint down the straight to win by 12 yards, he missed breaking the world record by 4.2 seconds. Nonetheless his time of 19:40.2 was a Scottish professional record. So great was the disappointment among followers of pedestrianism that the Executive of the Glasgow International Exhibition staged a special four mile race against time and arranged to give a valuable prize if he broke the record. The trial finally came off on the evening of Thursday, November 8th, 1888. The track, according to “The Scotsman”, “was officially measured and certified … [as] a guarantee to those who look upon Scottish performances as open to question.” Three well-known runners were entrusted with the task of pacing Cannon – Bob Hunter of Govan, J Ferguson of Greenock and A Arrol of Glasgow – each taking it in turns to draw Cannon out. the track was specially lit up for the occasion, and at eight o’clock in the presence of 10000 vociferous spectators the race got under way. there was a high, biting wind blowing throughout the race and having to run alone did not make Cannon’s task any easier. All he had to guide him as to his progress was the timekeeper’s call every half mile. Cannon set off at a quicker pace than five days earlier, passing the mile in 4:22.0 and two miles in 9:37.8. After the call at two and a half miles (12:06.2), he knew that he had the record within his grasp. Having covered three miles in 14:34.4, a time only he himself had bettered, Cannon went through three and a quarter miles in 15:47.0 and three and a half miles in 17:002.2 to reach the bell in 8:15.4. The crowd sensing a new record was imminent, the noise inside the enclosure grew to a deafening pitch as the excitement mounted. Straining every sinew, Cannon finished with a sprint to stop the clock in 19:25.4. Finally the record was his! Not only that, he had neaten the existing mark by fully 10.6 seconds! His intermediate quarter times from three to four miles were world records too.

Cannon was still hungry for success and, therefore, two world records were not enough. He would not rest until he had claimed the two, five and six miles figures as well! Another winter of hard training lay ahead. On 4th January 1889, Cannon began his quest with an assault on Jack White’s figures for five and six miles at Hampden Park, Glasgow. He had with him three pace makers – Robert Hunter of Govan, H McDermott of East Calder and Tom Graham of Lanark. the conditions were not ideal – a cold wind was blowing and the track was soft owing to a recent frost. When the race got under way at 2:35 pm a large crowd was present to cheer the Stirling man on, with the pace makers organised to draw him out mile by mile. He shrugged off the adverse conditions and gave it his best, passing the mile in4:45.6, two miles in 9:46.4, three miles in 14:52.0 and four miles in 19:59.4. However the record was never truly within his grasp that afternoon, and despite efforts by Graham and Hunter to shield him from the wind, Cannon slowed to reach five miles in 25:13.4 – a fine time but well short of the requisite 24:40.0. Ultimately it was too tall an order, even for a man of his ability. However a strong closing mile brought him to within 27 seconds of the record, and he breasted the tape in 30:17.0. Cannon at least had the consolation of setting a new Scottish professional record, eclipsing the previous figures of 30:18.4 set by his great rival, William Cummings during his record-breaking ten miles at Lillie Bridge on 29th September 1885.

From One Highland Games to Another: two in One Day

Following a successful summer campaign, with recent wins at the Strathallan Meeting and in the Great Three Mile Handicap at the Bute Highland Games, Cannon launched yet another attack on the two miles record. The undertaking took place on the ground of St Mirren FC at Westmarch, Paisley, on the morning of Friday 16th August 1889. Cannon ran strongly throughout, sprinting the last 200 yards, but again the record eluded him. the official timekeeper’s watch registered 9:13.0 – 1.5 seconds outside Bill Lang’s mark. Cannon was said to have remarked on finishing that he could have broken the record had he been pushed. Most runners would have been satisfied with a good day’s work, but not Paddy Cannon! Later that afternoon he put in an appearance at the Luss Highland Gathering in the picturesque village of Luss, on the shores of Loch Lomond. However after his hard work at Paisley, coupled with the fact that he had been over-handicapped, he had to be content with second place in the two mile handicap. Two weeks later, on 31st August, Cannon competed in the Two Miles Flat Race at the inaugural Highland Games and Sports in Belfast, Northern Ireland, where there was a large Scottish colony, thus ensuring a good attendance. Cannon was a little off colour, probably because of the long journey over from Scotland, but caught and passed every opponent but one. Compatriot Tom Graham took full advantage of 145 yards start to win by 30 yards in 9:42.2 to Cannon’s estimated 9:30.0. For Cannon the nig race of 1889 was only a month away: the One Mile Championship for a sweepstake of £1100 and Mr Lewis’s Silver Championship Cup. It took place at Victoria Ground, Govan, on Saturday 28th September 1889, The four competitors who joined in the sweepstakes were William Cummings, Preston, and Peter Cannon, Stirling, both off scratch; George Powell, Wales, 30 yards start and Fred Goodwin, London, 66 yards. Each man had laid a £25 stake. Cummings was the holder having won the first race at the same venue twenty months earlier. An immense crowd of spectators filled the enclosure and the stands, with most interest centring on the mile championship. In the days preceding the event, the Glasgow Herald had dampened any expectations of a phenomenal time by commenting that the ground “was not a good one” . Indeed the 352 yard track was heavy and on the day of the race a gusty wind was blowing. Cannon, reportedly “in capital condition”, was attended on by JM Campbell of Alexandria. Cumming was the bookies’ favourite on 7-4 on, while odds of 6-4 were being offered against Cannon. When the race got under way, Powell set off quickly and overhauled Goodwin in the second lap but then retired, suffering from cramp. Cannon and Cummings ran side by side, and the Stirling man tried earnestly to shake off his opponent, albeit without success. The first four laps took: 48 and a quarter, 1:41 and three quarters, 2:36.0 and 3:35 respectively, and after Goodwin was passed the race took on an air of inevitably for Cummings was a 52 second quarter miler. Sure enough when they entered the home straight Cummings pulled out and, amid thunderous cheering, romped home the easiest of winners by six yards, smiling and looking back. The times were as good as could be expected: 4:28 and three quarters for Cummings and an estimated time of 4:29.9 for Cannon. Being from nearby Paisley, Cummings was a popular winner. By retaining the Mile Championship, he not only won the sweepstakes but after the race, Cummings announced his retirement from racing after having already announced his intention to do so.

The Clans Gather in Paris, and the “Great Champions” race at One Mile

In the autumn, Cannon crossed the English Channel to represent his country in the Gathering of the Clans in Paris as part of the Exhibition. This unique sporting event saw the greatest number of Scots descend on the French capital since the days when the Scots furnished a fighting contingent for the Kings of France in the 16th and 17th centuries. However, instead of men-at-arms, this particular Scots contingent – some 300 strong – consisted of bagpipers, wrestlers, caber tossers and, of course, athletes. There were ten entries for the ‘Great Champion One Mile Race’ on Thursday, October 17th, 1889. They included Will Snook and Joe Hind of Carlisle, but neither man had shown good form that year, and Cannon was the favourite. The race was not so much fast as controversial, for Cannon was badly fouled by both Snook and Hind in the closing stages and he could only finish third. However, the stewards ruled in his favour and awarded him the win, much to the displeasure of the English supporters who in turn cried “foul”. Snook who had been first past the post was relegated to second, and Hind to third. the ruling made a great difference to Cannon’s pocket, for the first prize was 50 guineas, a gold vase and the medaillion d’honneur de Paris (Paris Medal of Honour). In the four mile champion race the next day, Cannon with a point to prove, set off quickly and ultimately ran out an emphatic winner, finishing a quarter of a mile in front of Snook in 20:34 and three quarters. The French spectators were said to have been awestruck by his running. For his efforts, Cannon collected 100 guineas and another gold vase and medaillion d’honneur de Paris, making the trip to France a highly profitable venture.

Just as Cannon was at the pinnacle of his career, a leg injury caused him to break down in training. The injury was so serious that it wrecked the first half of the 1890 season. A proposed three race match against J Courtney of Portsmouth fell through and tentative plans to go to America and compete against their best professionals also had to be shelved. The trip to Paris had evidently whetted Cannon’s appetite for racing abroad. Cannon eventually made a recovery and when he won the two mile handicap at the Glasgow Police Sports in 10th May 1890 he knew he was back on track. Injury or no injury, Cannon evidently had his mind set on racing in America, and in early June 1890, he sailed out of Glasgow on SS Ethiopia, travelling under his alias, Peter Cannon. Upon his arrival in New York, Cannon stopped with a friend in Brooklyn and let it be known that he was ready to accept engagements with “any man in America”. Despite securing the services of MJ Finn of Natick as his manager, Cannon’s search for competition at first proved fruitless. His main would-be adversaries, Peter Priddy of Pittsburgh and James Grant of Boston were playing hard to get, demanding that he put up $1000. After failing to secure a match within several weeks of his arrival, a disappointed Cannon was on the verge of returning to Scotland when the Caledonian Club came to the rescue. Scots accounted for a large share of the immigrant population in North America, and consequently most major cities had their Caledonian Club or a similar organisation, which served to promote the musical, Literary and social heritage of Scottish culture. The premier event in the calendar of any Caledonian Club was the annual Scottish Highland Gathering and Games which naturally were similar to those typically held in the Motherland. And so it was that Cannon participated in the 37th Annual Picnic and Games of the Boston Caledonian Club at Oak Island Grove, Revere Beach on Thursday 28th August 1890. The club had put up $2000 for professional athletes and a good field was thereby secured, upwards of 15000 spectators paid their admission to watch the event. the bustling ground was awash with men in kilts and echoed to the sound of bagpipes.

Cannon was entered for the five mile scratch race. It was the event of the day and had been the principal topic among athletes in the month leading up to the Gathering. The Caledonian Club had allocated some $300 to this race alone. Cannon was up against stiff competition in the shape of James Grant, Boston; Peter Priddy, Pittsburgh; Ed McLellan, Pittsburgh; Dan Burns, Elmira; and Nick Cox, New York. Grant, the local hero, was tipped to win, having set an American five mile professional record of 25:22.3 at Cambridge, Mass, only three days earlier. Cannon must have been mortified by his billing as “Peter Cannon, Champion of England”! Ed McLellan set the pace from the second mile onwards, reaching three miles in 15:49.0, with only Cannon and Priddy for company, and Grant who was suffering from cramp 50 yards in arrears and practically out of the race. Three and a half miles were dispatched in 18:35.0 and four miles in 21:21.0. the order remained unchanged until a quarter of a mile from home, when the Pittsburgh duo set about themselves, much to the detriment of Cannon, who lost contact, McLellan producing the better finish to win by 20 yards in 26:37.5. Priddy was second and Cannon third. A newspaper reported that “Cannon was left by the two Americans as if anchored”, but without detracting from what was a respectable performance under the circumstances. On 1st September, Cannon competed in the five mile race in Philadelphia, PA. It was the feature event of the annual athletic sports promoted by the Philadelphia Caledonian Club at Rising Sun Park. A crowd of 5000 “canny Scots” witnessed a close race between Pennsylvania’s own Peter Priddy and Cannon, the former winning in an astounding time of 24:30 which suggested that the track was considerably short. Only three days later, Cannon was back in action at the 34th Annual Games of the New York Caledonian Club at Jones Wood and Washington Park, New York. He was entered for the three and five mile scratch races both of which were open to all-comers. In his first event, the three miles, victory went to Peter Priddy in 15:40, Cannon comin in second before an audience of 10000 ebullient spectators. The subsequent five mile race provided the most thrilling finish of the day. British ex-patriot Nick Cox of New York took the lead from the start and set a stiff pace which only Cannon and Priddy were able to match. Cannon moved to the front half a mile from home and began a long drive but Priddy went right after him and took the lead, both men dropping Cox. Thus it remained until the finishing straight when Priddy and Cannon engaged in a mad scramble for the line, Priddy winning by inches as both men clocked 26:59.0. After a week of frenetic activity Cannon concluded his racing tour of America, packed his belongings and bade farewell to the Land of Opportunity. The 1890 season had been one of mixed fortunes. Apart from his racing tour of America, the year had marked the birth of Cannon’s first child, John. Over the next decade, the family would grow to include another four boys and a girl.

Paddy Cannon did not so much retire from professional running as to fade away. Age was beginning to creep up on him and after the injury-plagued 1890 season his performances began to slip. Cannon was now at the crossroads. with the responsibilities to think about, his first priority as a parent was to feed and clothe the family. The money from pedestrianism was a supplement, no more, no less. His regular income came from working on a farm where he prided himself on being a threshing machine operator although this was generally considered a hazardous job. Threshing engines were designed for the removal of husks from grain to make flour. They had various moving mechanical parts and their operators literally risked life and limb. A contemporary newspaper tells of a woman threshing machine operator who “had her clothing caught in the machinery and one of her legs drawn and dreadfully mangled”. Another tells of a foreman who “put his hand too far into the beaters while feeding the machine and the beater tore a finger from his hand.” From 1890 onwards, Cannon confined his competitive outings mainly to weekends and public holidays. He continued to compete at Highland Meetings for several more seasons and, for a time at least, continued to pull crowds thanks to his undiminished popularity. He held on to his scratch man status for a while, albeit conceding ever decreasing starts as his biological clocked ticked onwards. At the Blackford Highland Games on August 10th, 1891, he won the two miles off scratch but had to settle for second to John Taylor of Kirkcaldy in the mile handicap after finding himself unable to make up the handicap of 25 yards on the latter. On August 27th 1896, Cannon, now in his 40th year, was third in the two mile handicap at the Abernethy Games where, remarkably, he was still the backmarker!

By now however he was generally receiving rather than giving starts and, therefore still enjoying a modicum of success at meetings. At the Jedburgh Games on July 11th 1896, he competed in three events, winning the ‘Basket and Stone’ race (winning £1), finishing third in the ‘Go as you Please competition’ and winning the two mile handicap (winning £1 10 shillings).

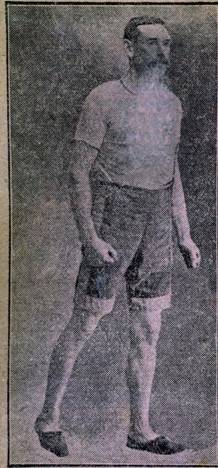

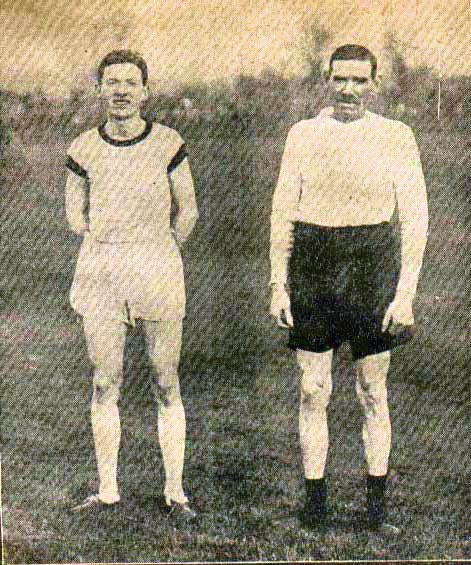

An older looking Paddy Cannon dressed in running kit

Two weeks later, at the Kelso Gathering, he had another payday when he finished third in the half mile handicap off 65 yards, third in the two mile race and second in the mile handicap off 75 yards. The following year Cannon competed at the Strathallan Games in the two mile handicap, which featured Anglo cracks Harry Watkins and Fred Bacon. He started from the 75 yard mark alongside T Conchie of Shap who provided a turn-up for the books by winning in 9:33.2. A newspaper described it as a “very punishing race”, adding gallingly that “veteran P Cannon [brought] up the rear.”

One Sporting Career Finishes, Another Opens.

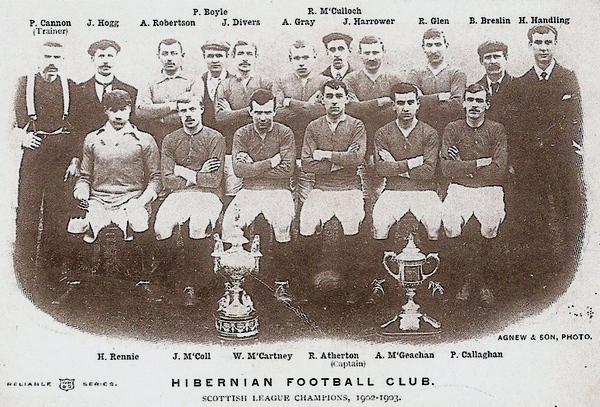

However, little did Paddy Cannon realise that as the curtains were coming down on one great career, another exciting career was about to take off! In 1896, Cannon took on a job as the groundsman of Hibernian Football Club (Hibs) in Edinburgh. He enjoyed outdoor work and coming from a Catholic-Irish household, was a loyal Hibs supporter. It was something of a dream job for Cannon, and would be the beginning of an association that would last for almost half a century. The family moved to Edinburgh and into a tenement at 9 Lyne Street in the aptly named Canongate district which then had a large Irish population. Hibs were founded by Irish born football enthusiasts in 1875 and named after the Roman word for Ireland. Hibs early years were turbulent. In 1887 they won the Scottish Cup, but the following year they almost went out of business when a number of their best players defected to the newly formed Glasgow Celtic Football Club. The game wasn’t professional in those days so no money changed hands directly. However Celtic lured away the Hibs players by offering them businesses such as pubs and shops. Consequently Hibs struggled to field teams during the following seasons. Things went from bad to worse when their treasurer emigrated to Canada with a large portion of the club’s funds. The upshot was that the club went defunct in 1891. A reformed club called Hibernian Football Club was established in 1892 and acquired a lease on a site at Easter Road which is still their home to this day. Hibs fortunes took a turn for the better when their committee promoted Paddy Cannon to the post of trainer-groundsman in 1897 thereby enabling the club to draw on Cannon’s experience and knowledge of conditioning for athletic performance.

Cannon put his charges, many of whom were young players, through a new training regimen destined to reap benefits in the longer term. His training methods were considered innovative and modern in that era and he was highly respected by the Hibs players of the day. The young Hibs players blossomed under his tutelage, and with club secretary Dan McMichael holding the reins, Hibs reached the final of the Scottish Cup in 1902. The week before the final, Cannon primed his charges for the big challenge with long walks to Portobello, dominoes at night and a “diet of thick potted-head sandwiches washed down with cups of milky cocoa.” It was his unique way of fostering good team spirits. The plan worked perfectly: the Hibs team gelled together to beat Celtic 1-0 in the final, which bizarrely was contested at Celtic’s home ground of Parkhead Stadium. The following year Hibs won the Scottish League title for the first time in impressive style, amassing 37 points in 22 games to finish six points clear of Dundee FC. Arguably the period between 1901 and 1903 was the finest in Hibs history when they were concurrent holders of the Scottish Cup and the Scottish League Championship Trophy. Hibs have won the Scottish League Championship three times since then but have never repeated their Scottish Cup victory of 1902.

Of course other clubs were quick to follow the example set by Hibs. “Levelling the playing field” so to speak. Hibs would never again reach those lofty heights during the remainder of Cannon’s tenure as their trainer but they performed by and large consistently during this period, save for a bad patch during the First World War and were never once relegated.

Like Father, Like Son: Another Cannon on the Track

Cannon’s son Tom was cast from the same mould as his father and shared his father’s passion for running and football. Not surprisingly, he also followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a professional runner and later a football trainer at Hibs. It was probably his son Tom’s running aspirations which induced Paddy to make a sensational comeback on the pedestrian scene in 1918 at the ripe old age of 61. A nostalgic match over half a mile was arranged between himself and his old adversary William Cummings at Ibrox Park, Glasgow, on August 17th 1918. Even in old age, Cummings (60) was still the faster of the two men over the short middle distance, winning by 30 yards in 2:49. Sadly this was to be Cummings last appearance on the running track. he died the following year in a Glasgow hospital. At the same Ibrox meeting, Banknock coal miner George McCrae eclipsed William Cummings’ ancient 10 miles record with a time of 50:55.0. Earlier in the year McCrae had also erased Cannon’s three miles mark of 14:19.5 from the record books with a time of 14:18.6. George McCrae was, as it were, the “spiritual successor” to Paddy Cannon. In fact, McCrae was the first Scottish runner since Paddy Cannon’s heyday to be truly worthy of such an epithet.

The following year, Cannon entered the Powderhall Marathon alongside his son Tom. remarkably, the distance, ten miles, was the farthest he had ever raced! Of course given his age, he was the limit man with a start of nine laps. the veteran Hibs trainer tenaciously defended his lead for fully half of the distance but then had to yield to his younger rivals. He eventually finished fifth, just outside the prize list having covered seven miles in about 52 minutes. For a man approaching 62 and on a heavy track and in cold conditions, it was a creditable performance. The new ten miles track record holder McCrae finished eleventh in the handicap but did enough to win the £25 and the challenge cup for the fastest time (53:32.0). What an occasion it must have been witnessing those two greats of Scottish distance running, Paddy Cannon and George McCrae running in the same race.

As heart warming as it was to see the old champion back in action after all these years, Paddy Cannon never intended to make more than a brief comeback for the sake of the family album, as it were. From then on he left all the running to his son Tom who developed into a 4:30 miler and flew the Cannon family flag for several years, winning various Powderhall handicaps over the mile and two miles. In the early 1920’s, Paddy Cannon retired from active trainer duties and handed over the reins to his son and fellow pedestrian “Di” Christopher of Currie. However, he remained loyal to Hibs and worked as their groundsman until old age compelled him to give that up too. He was blessed with a long and healthy life and remained a loyal football and athletics enthusiast until his death in his ninetieth year at City Hospital, Edinburgh, on August 23rd, 1946. His wife Annie died three weeks after him. In the late 1920’s a journalist writing in praise of Paddy Cannon created what is actually a fitting epitaph to the man:

“He was a great athlete and a sound trainer, and the pity is that Scotland cannot raise more of Cannon’s kind.”

Paddy Cannon’s Personal Best Performances

| Distance | Time | Venue | Date |

| 880 yards | 2:09.5e | Dublin | 13 June 1886 |

| 1500m | 4:10.5e | Edinburgh | 23 July 1887 |

| Mile | 4:29.9e | Govan | 28 Sept 1889 |

| 2 Miles | 9:12.5 | Govan | 28 July 1888 |

| 3 Miles | 14:19.5 | Govan | 14 May 1888 |

| 5000m | 15:05.2 | Glasgow | 8 Nov 1888 |

| 3.25 Miles | 15:47.0 | Glasgow | 8 Nov 1888 |

| 4 Miles | 19:25.2 | Glasgow | 8 Nov 1888 |

| 5 Miles | 25:13.4 | Glasgow | 4 Jan 1889 |

| 6 Miles | 30:17.0 | Glasgow | 4 Jan 1889 |

I hope and think that you will agree that the above comprehensive account of the life and times of a wonderful athlete sheds some well-deserved light on an athletics scene similar to our own but of which too little is known by the present generation.

Brian Scobie

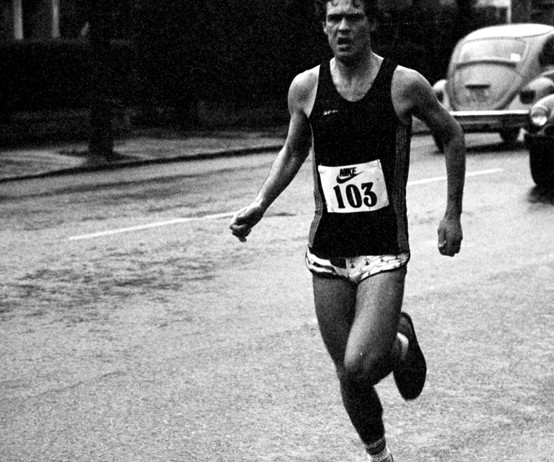

Brian Scobie winning at Westerlands, Glasgow, in early 60’s

Brian Scobie (born on 16th May 1944) was a very good runner who represented Maryhill Harriers and then ran for Glasgow University AC in the 1960’s, before becoming a very highly regarded and much respected coach in the 1980’s, 90’s and into the 21st century. Brian ran while at school and his father was also interested in athletics. Living in Milngavie, he was eligible for the Dunbartonshire team in the Inter-Counties Youth Sports which was an annual athletics contest between the young athletes from local government authorities and was not a school or club based competition – athletes from schools, clubs, youth clubs, youth organisations, and whatever else were eligible so long as they had demonstrated ability. Brian was only eleven months younger than Lachie Stewart from the Vale of Leven (also eligible for Dunbartonshire) and their paths crossed frequently in these sports. With age groups in two year bands, they were in direct opposition every second year. They competed together several times in that context. Like many another, Brian describes himself as a ‘would-be footballer’ who ran a bit in the summer but did no formal training. He did have a paper round however on six days a week with a circuit of about 6 miles. Sometimes he cycled the route, sometimes he ran but from second to sixth years at secondary he was covering, one way or another, 30 miles in total.

In summer 1961-62 – the year before he went up to University – he was training with Queen’s Park FC Youth team at Hampden where they were not allowed even a sight of a ball until they had done 12 laps of the old cinder track. Then there was a series of sprint sets – eg from one corner flag to the other, then from the tunnel to the corner flag, then from the edge of the eighteen yard box to the corner flag. This, together with the school PE teacher he had, meant he won the County 440 yards and then finish second in the Scottish Schools 880 yards. At that point he joined Maryhill Harriers and started training with Tom Williamson’s group. He gained a reputation as a good competitor who could frequently win tactical races. Jim McLatchie the very good miler and middle distance runner from Ayrshire, moved to Milngavie and immediately the two started doing a lot of their training together, regularly training with the girls of Glasgow Western LAC under Tom Williamson’s guidance in the west of Glasgow. If we take a look at his time with GUAC it is quite impressive. He did not make the schools international mainly because, despite a good racing record, his times were not as fast as some others. He had run in many highland games meetings and became a good tactical runner but tactical success doesn’t always mean fast times. The performances of others such as Kenny Oliver and Davie Hendry in Dublin also rightly counted with the selectors of course. He ran in a floodlit international; at Ibrox in September with such as Hugh Barrow in the Scottish team in a race won by England’s Morris Jefferson.

Brian first ran for Glasgow University in winter 1962-63. Previously a summer runner, he had no experience of cross-country before joining the Hares & Hounds. His initiation to the arts of cross-country running came when he ran the team trial, then went with the club to Belfast the following week where he was a very good third on the Saturday (27th) and then they went on to Dublin on Monday 30th where he was second to team-mate Cameron Shepherd, beaten by 12 seconds but four seconds ahead of Shillington of Trinity College. The first real domestic race with them was the Edinburgh to Glasgow relay in November 1962. He ran on the eighth stage and held third place – holding off Chic Forbes (VPAAC) and Les Meneely (Shettleston Harriers) to win a bronze medal. His next run in a winter classic was in the Nigel Barge Road Race on 5th January, 1963, when he finished 36th and third counter in a GU team that finished fourth and just out of the medals. A week later in a match against Edinburgh University at Garscadden in Glasgow, he was fifth and third counter in a Glasgow team that won 26 – 52. On 19th January he was sixth counter for the university in the Midlands District championship when he was 29th for the second placed Glasgow squad. In action for the fourth consecutive week, he was in the winning team in a match in Glasgow against Aberdeen AAC, Aberdeen University, University, St Andrews and Dundee Hawkhill finishing eighth and fourth scoring runner for the University. In a race featuring Calum Laing, Alastair Wood, Steve Taylor and Allan Faulds, eighth was not a bad run and the official history of GU AC comments that it was a confirmation of his return to form. These races were the lead-in to the Scottish University championships on 2nd February when he was tenth, third counter in the team which finished second to Edinburgh. In the National cross-country championships for Glasgow University on 23rd February, 1963, he finished twenty second for the team that won the bronze medals with 119 points behind Edinburgh University (49 pts) and Edinburgh Southern Harriers (91 Pts).

Brian ran over the summer and on 20th April finished first in the 880 yards in a match with Edinburgh University finishing in 1:59.5, assisting the Glasgow team to an 88 – 45 victory. Although he undoubtedly raced al that summer, he was too young and too inexperienced to take on the many ‘big beasts’ competing in the country’s middle distance events – an area where Scotland was particularly strong at that time with runners like Lachie Stewart, Ian McCafferty, Graeme Grant, Dick Hodelet, Duncan Middleton, Fergus Murray and many more.

Season 1963 – 64 was a better one for him. Running for the Hares & Hounds over the following winter, Scobie ran in the team trials on 19th October, 1963, and finished fifth behind such strong runners as Allan Faulds, Dick Hartley, Calum Laing and Jim Bogan with Dick Hodelet sixth. A cutting from a University paper said that “the reprobate Scobie finished fifth as expected in 41:05.” Not a regular in the first team, he ran in the Edinburgh to Glasgow in November 1963 on the short third stage and pulled the team from seventh to sixth. Followed by Dick Hodelet who picked up another two places, the University scribes felt that they had both run very well. On 23rd November at Kings Buildings, Edinburgh, in a match against Aberdeen University, Edinburgh University, St Andrews University and Edinburgh Southern Harriers, Scobie finished eighth – second Glasgow Scoring runner for the team which finished second to Edinburgh University. On 7th December, he was second in a match against St Andrews to be second counter in 37:20 for the winning University team. Into the New Year and Scobie was third in 38:08 to be second scorer in the winning team against Edinburgh U H&H over a six and three quarter mile trail. A week later on 18th January in the Midland District Championships he was twelfth and second scorer for the fifth placed team. On 25th January it was back to Aberdeen to meet Aberdeen University, Aberdeen AAC, St Andrews University and Dundee Hawkhill over 6 miles of road and country where Brian finished third individual and second Glasgow man in the winning team. On 1st February in the Scottish Universities Championships Glasgow won the team race with Brian Scobie in sixth place after seven miles of road and country. Later in February he ran in the Junior National and finished twenty third in the Glasgow squad that was eighth. At the club AGM on 27th April, 1964, Cameron Shepherd the club captain made his report in which he commented on the fine running of Calum Laing, Allan Faulds, Brian Scobie and Terry Kerwin and followed this up by saying that Brian Scobie had had an exceptional season and the Club was very disappointed that he had not been awarded the Blue for which he had been nominated. It was however awarded the following year.

There are of course team contests on the track in the form of relays and Brian, a good team player, was in the winning teams for the 4 x 440 yards championship in 1963 (3:19.3) and 1964 (3:19.1) and ran the half mile leg of the winning team in the Mile Medley Relay in 1964 (3:36.6).

As the winter work would have led him to a high level of fitness, Brian began the summer season on 2nd May in a match between Glasgow University, St Andrews University and Queen’s University, Belfast, at Westerlands. Running in the Mile he was second to Glasgow team mate J Wilson who won in 4:24.8. A week later in the University’s confined championships he was third in the Mile, won by Dick Hodelet in 4:33.8 with Ray Baillie second, and second in the Three Miles, won by Calum Laing in 15:34.7. As in 1963, the very high standard of competition in his favoured distances was so high that he did not appear in any of the other championships that year – not District, British Universities nor SAAA. Nevertheless by the end of the season he was ranked 14th in Scotland over 880y with a best time of 1:55.6.

The first winter classic is the Edinburgh to Glasgow relay and in season 1964-65 Brian Scobie ran on the first stage and finished seventh. The rest of team failed to hold this place and the team was fifteenth. In the District Championships, Scobie finished twenty second and the University team was fifth, and again the official history comments on the individual performances of Scobie and Shepherd. Both were selected to run in the race against the UAU , and Scobie along with Barclay Kennedy and Ray Baillie was selected to run for Scottish Universities against a Scottish Cross-Country team. He was, with four others, awarded First Team Colours and the report goes on to say “The outstanding member of the Hares and Hounds over the season had undoubtedly been Brian Scobie; this was recognised by his winning of the Esslemont and McCulloch Trophies and the award of a Blue.” He had been captain that winter and in his report he commented on the drop in standard of team performances following the graduation of several first team members. Citing Barclay Kennedy as an example he said “that no-one could claim that Barclay was built as a cross country runner, and yet he had reached the standard of a Scottish Universities’ Select.” He stepped down as captain at that meeting at the end of the winter season.

After this excellent winter, he started the next summer concentrating on what many felt was his best distance, the half mile. On 24th April, 1965 Brian Scobie was part of a Glasgow team that defeated Aberdeen University in Glasgow. He won the 880 yards to get the season off to a good start and the ‘Glasgow Herald’ reported: “Bill Ewing of Aberdeen was well contained in the 880 yards by BWM Scobie (Glasgow University) who gives every indication of being an even better runner than he was last year. Scobie had the race in control from the start and led Ewing over the finishing line by about five yards.” On 1st May in Belfast against Queen’s, Belfast, and St Andrew’s, Scobie was again out in the half mile. It was a windy day, witness this on the 880 yards, “After allowing lesser mortals in the 880 yards to act as hares, BWM Scobie (Glasgow) broke away with half a lap to go and won in 2:01.2, a time that on any other day but Saturday he would readily have scorned.” Only one week later was the Glasgow University AC club championship and it was again a day of strong winds, so strong that the officials allowed the 100m competitors to run with the wind rather than against it. Pity there wasn’t the same opportunity for the half milers – but Brian Scobie won the title anyway in 1:58.9 and the Mile in 4:38.1. On the last Saturday in May, Scobie was third in the West District 880 yards behind Graeme Grant and Mike McLean – not a disgrace to be behind these two fine runners. By the end of the season he had a best of 1:54.6 which ranked him sixteenth in Scotland.

I have spoken to several of his contemporaries at University who have all – without exception – said that he did not achieve anything like his potential as an athlete before graduating.

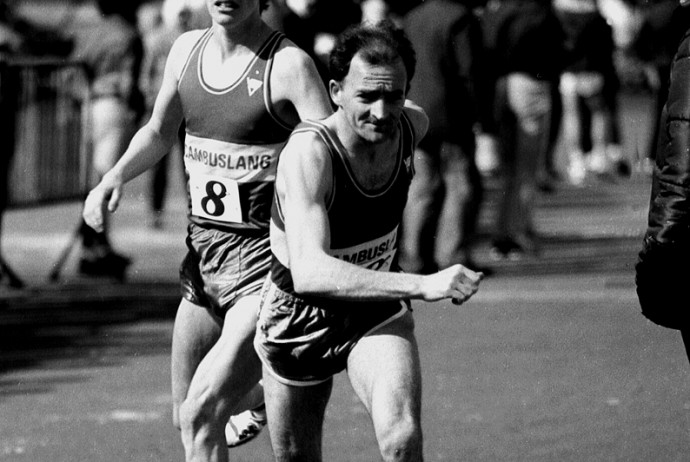

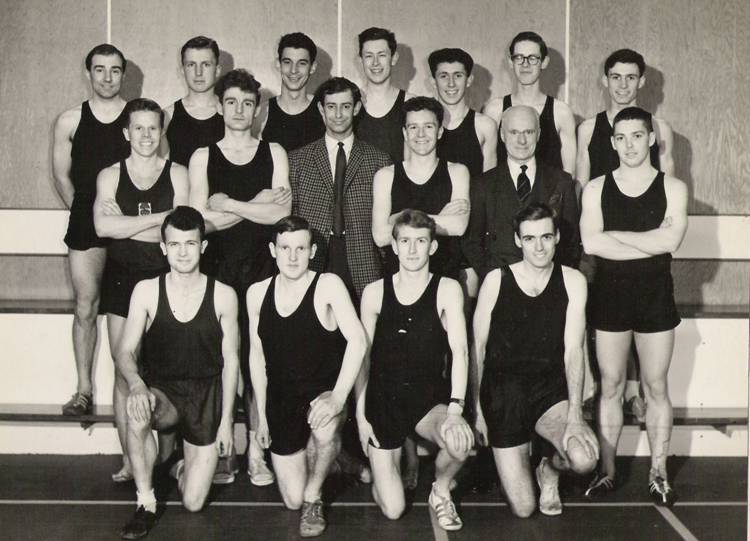

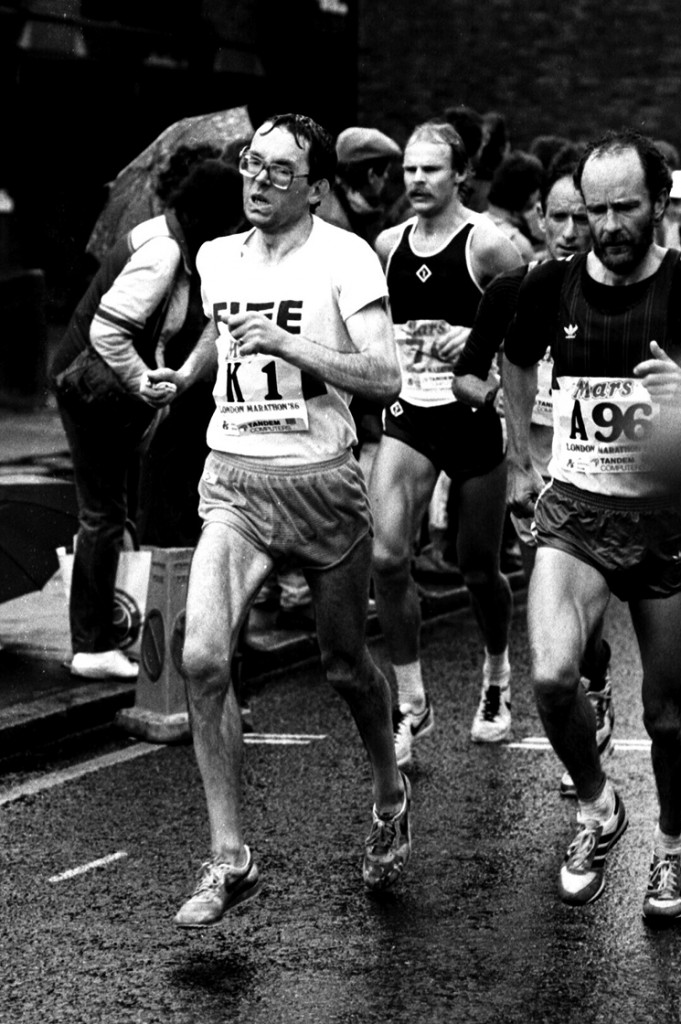

London Marathon, 1986: Brian Scobie A96

Brian moved to Leeds as an assistant lecturer in English in Leeds University in 1969 and stayed there until 2001 – a period of 32 years. It was over this period that he developed his coaching skills and worked with many athletes of genuine quality – notably in the 1980’s when his squad of endurance athletes, particularly marathon runners, was arguably the best in Britain. Athletes in the squad included

* Veronique Marot, who was twice British record-holder, winner London Marathon, 2nd New York Marathon, three times winner of Houston Marathon (’86, ’89 and ’91)

* Angie Pain Hulley, two Commonwealth Games for England (6th and 3rd), A European Championship competitor, a World Championships runner and an Olympian

* Sheila Catford, Scottish Internationalist, winner of the Glasgow Marathon and Commonwealth Games competitor.

* Sarah Rowell, World Student Games marathon winner, second in London Marathon, third in the Columbus Marathon in Ohio and 14th in the Olympic marathon in Los Angeles

* Jill Clarke, world student marathon winner and 2:39:42 was fastest GB marathon debut until Paula Radford in 2002.

Julie Holland, currently number 24 on the UK all-time list for 10000m with 32:47:48

* Sandra Arthurton, an outstanding cross-country runner, multi international appearances.

* Peter Whitehead who finished fourth in the World Marathon Championship (interesting article at www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/sport/other-sport/athletics/merseysides-100-olympians-no-60-3345933 )

* John Sherban – Commonwealth Games athlete

There are many more and those cited have all done much, much more that can be noted in this profile of their coach, Brian Scobie. At this point he himself made a come-back to competitive athletics but at a much further distance than in his GUAC days – marathon running no less. His first run at the distance was in the inaugural London Marathon in 1981 with some of his club mates in a time just outside 2:36. He ran marathons very well indeed. He ran London in 2:24 and 2:23 with his very best being 2:21:50 in London in 1984. In 1986 the Scottish ranking lists had him at the age of 42 with marks of 30:52.8 for 10000m, and 2:24:14 for the marathon. But at a time when the ‘marathon boom’ was in full swing and times were all, Brian was still a competitive runner and had two notable marathon victories under his belt. Both were in the Horsforth Marathon. The first victory was ion the second race in the series in 1982 in 2:29:09 from a field of 488 starters. Two years later he won in 2:27:06. The time in ’82 was a record by 3 seconds but the 1984 victory took more than two minutes from his own record. That record still stands. The 80’s was a good decade for him and after the two Horsforth victories he won the Commonwealth Games vets 25 K in 1986, the Scottish veterans cross-country in both ’86 and ’87 and then later in ’87 won the masters category in Houston in 2:30:59. No small achievement – the Houston Marathon started in 1972 and by 1987 there were thousands running every year with the winner in ’87 being South Africa’s Derrick May in 2:11:51.

It is of interest to note that at this point in his career he was back working with his old Glasgow University athletics team mate Craig Sharp. Of this relationship Brian says: “Craig Sharp was President when I was running for Glasgow University. In 1965 I won the trophy that he had presented a year earlier. My subsequent re-connection with him was when he was heading the newly-created British Olympic Medical Centre, in Uxbridge. In the late 1980s we had a number of professional contacts in relation to my efforts to prepare Veronique for the Worlds and Olympics 1990-1992. Craig was very knowledgeable and very accessible and helpful at every point, friendly and assiduous. Through him I had a mobile lab-van trackside in Leeds at one point, doing lactate field-tests. (Try that nowadays!) So Craig was a big and positive influence for me from the 1960s to the 1990s.”

Brian Scobie, the coach.

Into the twenty first century and Brian Scobie is still working as hard as ever – that his work is successful is seen by some of the positions held:

From March 2003 to 2009 he was a Senior Performance Coach for UK Athletics before taking a post as Sprints Coach at Leeds Met University, a post which he held for a year. He then became an Area Coach Mentor, Endurance, for England Athletics in May 2011, a position which he still holds. What does it entail? “Mentor to Endurance Coaches in Yorkshire and Humber on behalf of the Athletics governing body in England; he has taken the post on a part-time consultancy basis. He is required to manage the England Athletics Area Endurance Coach Development Centre which is based at Leeds Metropolitan University. It involves organising and structuring all forms of coach education and speaking at venues across this huge part of the north of England. If we look at Linked In, his talents include Blind Sport Development, Paralympic athletics, Sprint Speed Coach, Marathon Coach, Endurance Coach. He has written on all aspects of coaching, several available on the web – eg www.sportscoachuk.org/sites/default/files/CE-Does-Disability-Make-Difference.pdf on the coaching of athletes with a disability.

In the context of working with athletes with a disability he works with Tanni-Grey Thomson and has been described as ‘her boss’ in her new job of identifying talent among those with a disability. He has also worked as Head Coach of the UK Athletics Paralympic Team. The involvement with Blind and paralympic sport should maybe be looked at and I asked Brian about it:

“As a result of getting fully engaged in the British Blind Sport project that John Anderson had invited me to be involved in from about 1982, I took a team to the 1984 paralympic event. I was co-managing with John Bailey who was unfortunately stretchered off the plane in New York with a suspected heart attack. So I had to manage and coach that very strong team at the event in Long Island. The event management was poor in many ways and I found myself battling heavily n technical meetings, etc, and having to raise issues for non-English speakers. As a result, I made friends but also some enemies. In the end it led to my involvement in the development and growth of blind sports in general within the governing body, IBSA. By the Atlanta Games I was the Technical Director, responsible for about 16 sports across five continents. In the early years of this involvement I also managed and coached Visually Impaired athletics but relinquished much of that role due to conflicts of interest. I was offered a post within UKA to establish the British team for the 2000 paralympics but was reluctant to quit my University post.”

And it didn’t stop there. Brian worked for a time as a sports development consultant. Many of the contracts he was involved with were funded by the Spanish organisation for the blind which traded under the acronym of ONCE, which translates as Spanish Blind Association. He undertook a number of projects with them and their partners in promoting disability sports. This not only took him to Africa and countries in Eastern Europe but led to his designing a programme for the UK to which he was later appointed as head. He was also involved with the IAAF and delivered a programme for developing countries at the World Championships in Lille.

Brian is still coaching club athletes, and he coaches athletes from a wide variety of clubs. The Power of 10 website credits him with 15 athletes from 9 clubs, covering distances from 100m to marathon, both men and women and ranging in age from Under 20 to M40 veterans. Let no one think he is now coaching at a lower level than heretofore: he always coached athletes of all abilities, bringing many through the ranks to international standard, and in 2013 one of his athletes, David Devine who runs the 800m, 1500m and 5000m in the T12 category, was included on UK athletics world class performance funding programme for 2013. If you are interested in how he trains his athletes and in the advice he gives to coaches, you can access a slide presentation at

www.slideplayer.com/slide/1679711/

It starts with the picture of the student Scobie winning a race at Westerland shown above and ends with a slide of him running in a marathon pack with Veronique Marot in the mid-80s, but it’s the content that matters.

His is a story of a lifetime’s involvement in the sport going from his days as a schoolboy in Milngavie, just outside Glasgow right up to the present day: and a commitment all the way through to excellence, encouraging the athletes he works with – able bodied and disabled, club standard and international class – to’ be all they can be.’