The Clydesdale Harriers’ Handbook for the season 1893-94 lists among its members a certain William Robertson, living at 2 Apsley Place in Glasgow District No. 4, the Gorbals.

It also enumerates the prizes each member won during the previous season. Robertson had 24: 15 firsts, 6 seconds and 3 thirds.

The story of Willie Robertson marks a watershed in the early history of Scottish amateur athletics. Late in 1898, only months after winning a clutch of S.A.A.A. titles, he was banished from the amateur ranks for life. This is the tale of an avid distance runner who aspired to become a star only to be sucked into a black hole. But, fear not, it has a redemptive ending.

Robertson was born to Janet and William Robertson, a draper, in Greenock, Renfrewshire, in 1871.

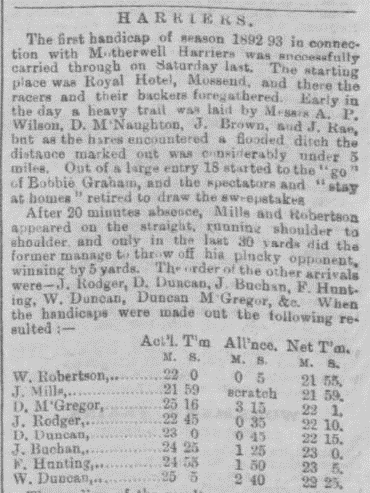

His sporting career began in Motherwell, where the family were living at the time. People tended to move around quite a bit depending on work prospects. Robertson was an apprentice pattern maker. He made his first public appearance in the colours of Motherwell Harriers in 1891.

On 6 February 1892, only a few months after joining Motherwell Harriers, he gave early proof of his precocity by finishing 16th in the Scottish Junior Cross-Country Championship at Paisley.

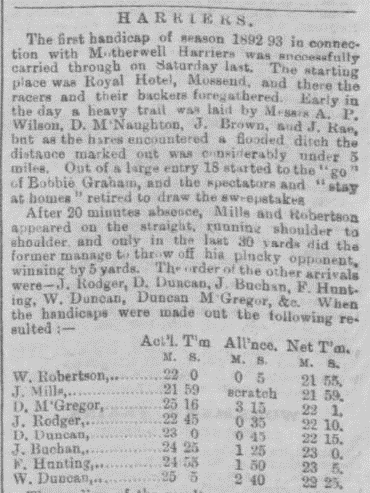

By the start of the 1892/93 winter season he was showing all and sundry at Motherwell a clean pair of heels.

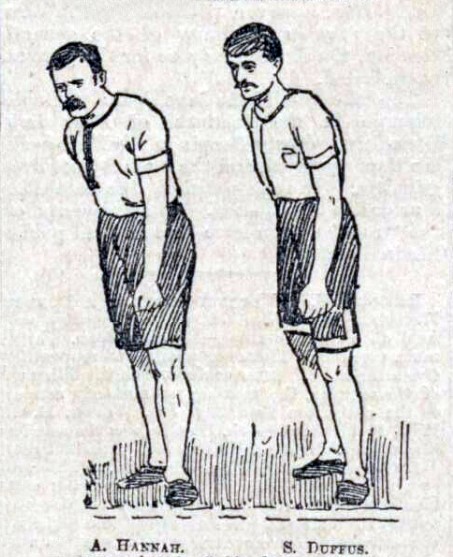

On 4 February 1893 Robertson took a second swing at the Scottish Junior Cross-Country Championship over a gruelling six-mile course across heavy plough and turf at Musselburgh. This time he showed what he was really made of by taking second place in of a field of 120 behind another outstanding young talent, Stewart Duffus from Arbroath.

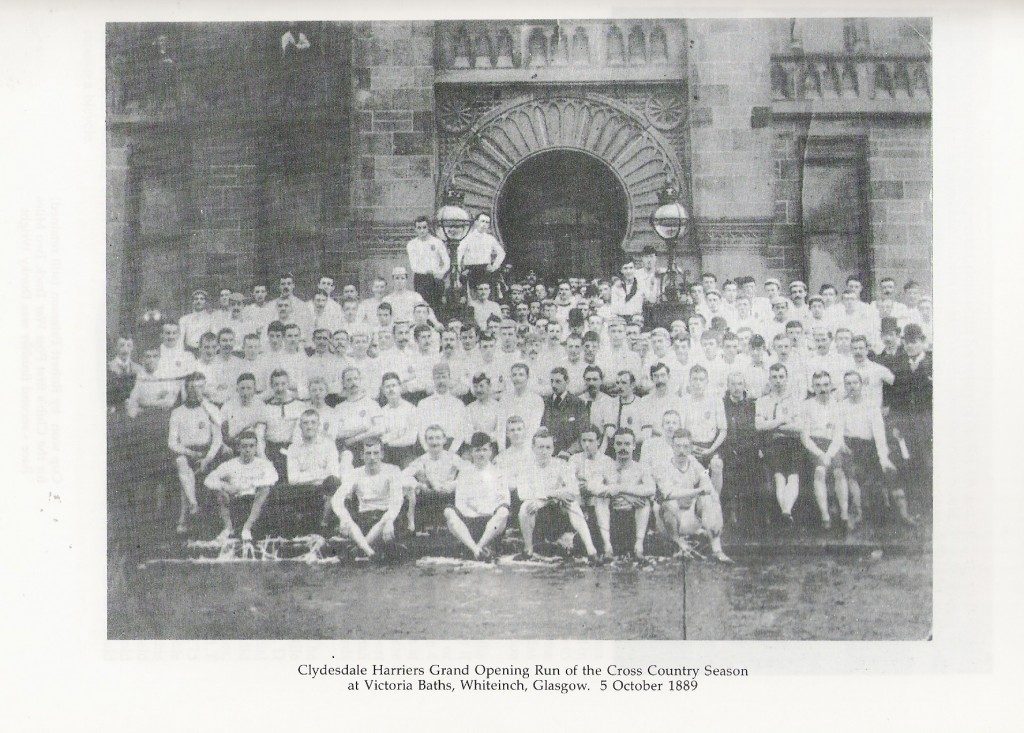

The overlords of the Western Districts must have seen Robertson as a potential reinforcement for their team fronted by multiple Scottish champion Andrew Hannah. The Clydesdale Harriers had developed talent recruitment to a fine art. With their unrivalled training facilities and a well-organised network spanning the entire Glasgow area, it would have been hard for an aspiring young athlete to turn down their solicitations.

After a few minor races to build up his form, Robertson scored a half / mile double at the Maryhill Harriers’ Sports on 27 May. “He is a cleanly built fellow, with a nice lift and taking style”, wrote Scottish Referee, adding prophetically that “Robertson … will yet be heard of.”

Two weeks later, in a two-mile handicap in Hampden Park, Robertson fulfilled this prophecy by demolishing a first-class field from 45 yards in 9:49.8. The race report in Scottish Referee was titled “ROBERTSON CAUGHT THE EYE”. It read, “The Motherwell man strode out from among the crowd with a stride like Triton, made mincemeat of the field, and paralysed everybody – handicapper included. There was no catching of him, and in disgust Hannah gave up a lap from home, but Duffus persevered, and got second place.”

The author also lamented that Robertson had not entered for the national championships. He need not have worried. Robertson, emboldened by his success at Hampden Park, submitted a late entry for the four-mile event, where he faced, among others, none other than Andrew Hannah. The Scottish Referee was in no doubt. “Robertson, Motherwell, is a cracker. He will stick the best men in Scotland at present”, it wrote.

The author did not omit to mention, however, that Robertson’s armoury lacked one vital tool – finishing speed. A chink in his armour. A vulnerability.

In the S.A.A.A. championships at Hampden Park on 12 June Robertson, as had been expected, gave Hannah a good run for his money. After having already run, and won, the mile earlier in the afternoon, Hannah was no doubt keen to conserve his energy for he settled on a tactical race where he was the predator and Robertson his prey. Despite his best efforts, Robertson could not do a thing, and on the last lap Hannah sprinted away and won by 20 yards in 21:36.4, with Robertson taking silver in 21:40.0.

Having represented Motherwell Harriers at the Scottish championships, Robertson transferred to the Clydesdale Harriers. His younger brother Thomas, a fairly good half-miler, also joined the Clydesdale.

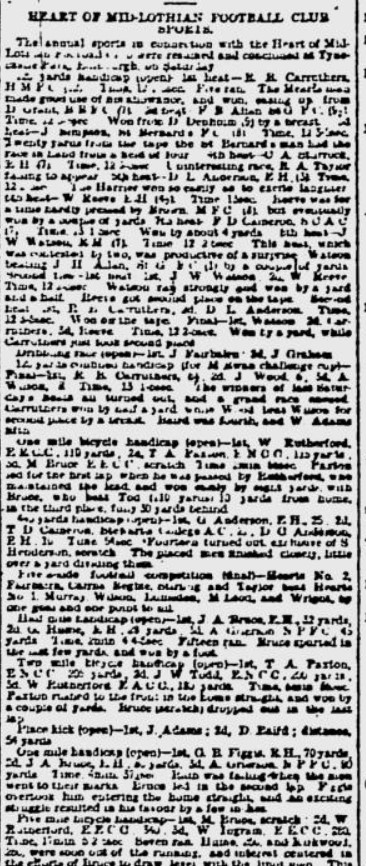

The rest of his season was less spectacular – the genie was out of the bottle – but at least it yielded a few more personal bests and benchmarks for future comparison. Robertson wore the Clydesdale colours for the first time in a three-mile team race at Tynecastle Park on 24 June but could only finish fourth in 15:36.1. On 22 July he covered the mile from scratch at Larkhall in 4:45.0, and then did 2:02.2 in the half mile off 30 yards. Finally, on 29 July he finished his track season by running second to Hannah in an inter-club three-mile race at Gateshead in an estimated 15:40.0.

It was around this time that the Robertson family moved from Motherwell to the Gorbals. The Apsley Place of the 1890s was a side street which cut a swathe between rows of tenements a short distance from the south bank of the Clyde.

Having been elected Vice-Captain under Hannah, Robertson kicked off 1894 by winning the first of the season’s classic events, the Scottish Junior Cross-Country Championship, at Hamilton Park Racecourse on 3 February.

A month later, he finished a creditable seventh in the Scottish Senior Cross-country Championship at Musselburgh, where his clubmate Hannah extended his dominance over the plough by winning the title for the fourth time in five years.

Robertson performed consistently, if not spectacularly, throughout the 1894 track season. At the Glasgow Merchants’ Sports at Celtic Park on May 19, he finished second behind Stewart Duffus in the four-mile handicap off 60 yards. Here he covered 4 miles less 90 yards in 20:41.4, which equates to about 21 minutes for the full distance. On 2 June he ran 15:33.2 in a three-mile inter-club match at Tynecastle, where he was outsprinted in the straight by the young Watsonian Hugh Welsh. In another three-mile handicap at the West of Scotland Harriers’ Meeting in Hampden Park on 11 June, he finished third and improved to 15:07.0 for 4 miles less 50 yards, or the equivalent of about 15:17 for the full 3 miles. He missed the 1894 S.A.A.A. track championships at Powderhall where Hannah won the 4 miles from Duffus, in 20:48.8. Twice he competed against the English champion Fred Bacon and on each occasion he was on the receiving end of a hefty defeat despite a sizable start. In a three-mile race at Powderhall on 21 July, Bacon set a new Scottish record of 14:27.4, while Robertson finished third off 270 yards. The same happened at Celtic F.C. Sports on August 11th, where Bacon covered the mile in 4:21.6, while Robertson finished second off 90 yards. Robertson ran his best mile that year on 18 August in Arbroath, where he won the mile handicap from 15 yards in 4:35.0.

Despite missing the S.A.A.A. championships, his overall haul for the year earned him the Clydesdale Harriers’ gold medal for the greatest number of prizes won during the athletic season – 27 in total.

Robertson opened the 1895 season by finishing fifth in the Scottish Cross-country Championship at Hampden Park, where 19-year-old Robert Hay of Edinburgh Harriers was a surprise winner, 100 yards ahead of Stewart Duffus.

The following month Robertson showed a marked improvement in the Scottish 10-mile championship at Hampden Park. Running with an easy, graceful action, he led at 3 miles in 15:31.6 and was able to stay with reigning champion Andrew Hannah through 4 miles in 20:47.8 before having to let go of his clubmate, who went on to shatter the Scottish record with a time of 53:26.0. Robertson held his form well and finished second in 54:07.0, just missing the old record.

In the run-up to the Scottish championships Robertson continued to show impressive form, winning a two-mile handicap off 30 yards at Paisley on 18 May in 9:43.0 and a mile handicap off scratch at Ibrox Park on 5 June in 4:33.6.

But something important had happened in the meantime. At the Vale of Leven Sports in Alexandria on 1 June, some eyebrows were raised when Robertson finished a close second in the half-mile handicap to Robert Langlands, Scotland’s #1 half miler at the time. His time of 2:00.0 for 880 yards less 24 yards is the equivalent of about 2:03 for the full distance, which was great running for a long-distance specialist. Three weeks later, Langlands would become the first Scottish amateur to break the two-minute barrier for the half. Not done yet, Robertson then lined up against Andrew Hannah in the mile handicap, both on scratch, and held his clubmate to a yard in 4:35.2. Athletic News reported that Robertson had been “cultivating a sprint” and that “at all events, there is more fire in his finish than was the case a year ago”.

The 1895 national athletics championships had been preceded by discord over whether professional cycle racing should still be allowed in conjunction with amateur athletics meetings. With revenue foremost in the minds of some, there were strong positions in favour and against the motion. The ensuing deadlock over this contentious issue resulted in several western district clubs in favour of allowing professional cyclists to compete at their meetings – notably Clydesdale Harriers – seceding from the S.A.A.A. and forming the Scottish Amateur Athletics Union (S.A.A.U.). This meant that athletes competing in events run under S.A.A.U. rules were automatically debarred from competing in meetings held under S.A.A.A. rules, and vice versa. The consequence of this impasse was that the national championships of 1895 and 1896 were held under the auspices of two separate bodies – much like in Ireland. Of course, it was to the detriment of the sport, for it also meant that Duffus, Hannah, Langlands, Robertson & co. would not get the chance to represent their country in the Scoto-Irish International instituted in 1895 under the auspices of the S.A.A.A. The depleted Scottish team only narrowly lost the first match but would probably have won it if they had been at full strength.

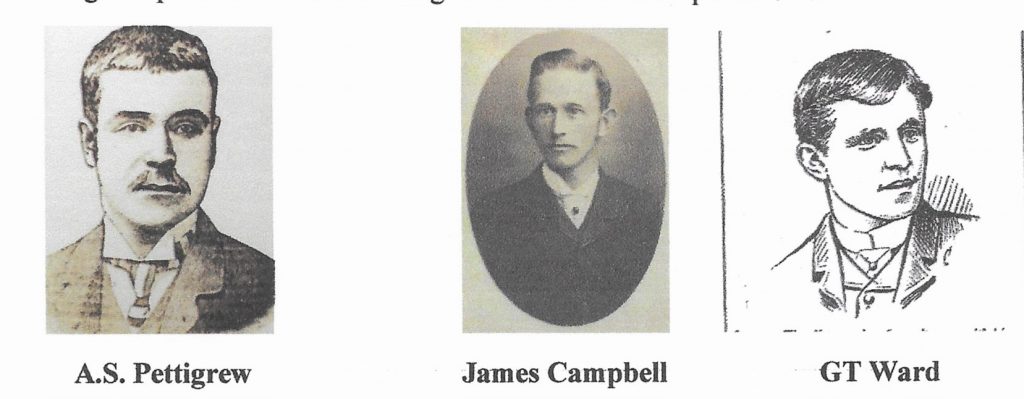

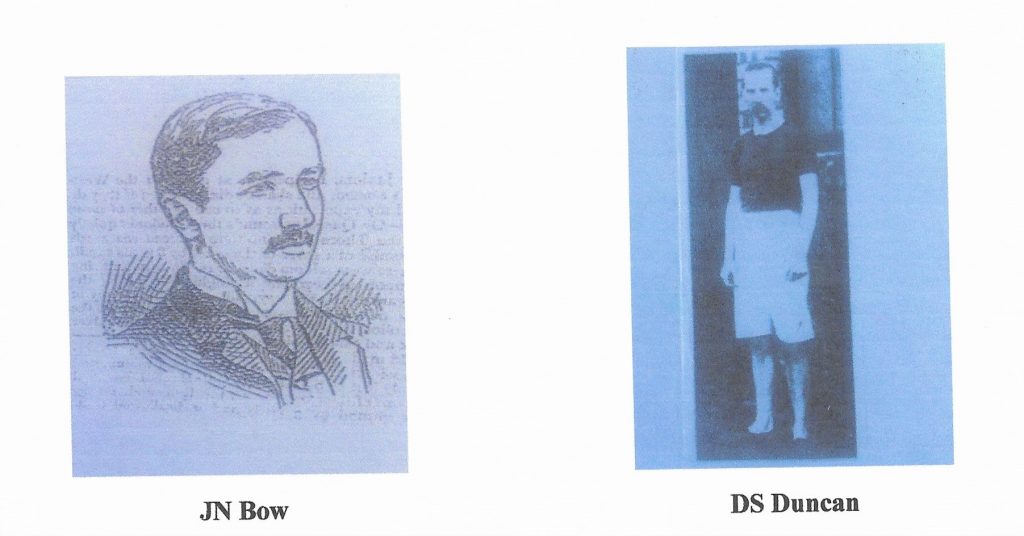

Despite the absence of competition due to the above-mentioned split, Robertson still faced a tough battle at the S.A.A.U. Championships at Hampden Park on 22 June. His opposition in the mile included John Milroy (West of Scotland Harriers), James Rodger (Carrick Harriers), Stewart Duffus (Arbroath Harriers) and Robert Langlands. Although a close race had been expected, Robertson left his opponents floundering in his wake and won by a full 70 yards from Langlands in 4:28.4. Without anyone pushing him, he missed the Scottish record set by David Scott Duncan in 1888 by only four tenths of a second. As to this, the Glasgow Herald commented: “If any man in Scotland is capable of this it is W. Robertson, whose consistent running has been one of the features of the season”.

Robertson continued his good run of form throughout the summer, even if he suffered two narrow defeats over two miles at the hands of Stewart Duffus, losing by a foot at Ibrox on 29 Jun in 9:58.1 and by inches at Dundee on 13 July in 9:57.5. On 17 July he won the mile handicap at Kirkcaldy in 4:28.0 off scratch. It equalled the Scottish record, but since the time was achieved on a grass track, it was not eligible for record purposes. Only three days later he produced another superb performance in the mile at the Falkirk F.C. Sports where he won easily off scratch in 4:29.2. At the Rangers FC Sports at Ibrox Park on 3 August, he again came agonisingly close to the mile record, winning in 4:28.4 from scratch. The Glasgow Herald attested Robertson a “magnificent race” and suggested that the record would have been broken without the “indiscreet pacing of his companions” Stewart Duffus and James Rodger running alongside him.

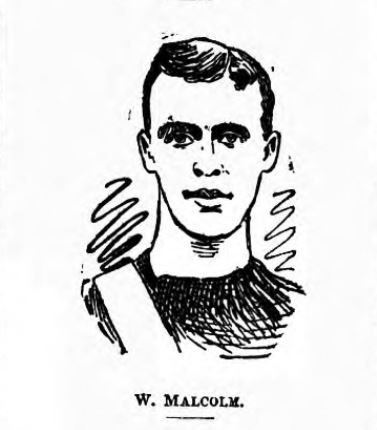

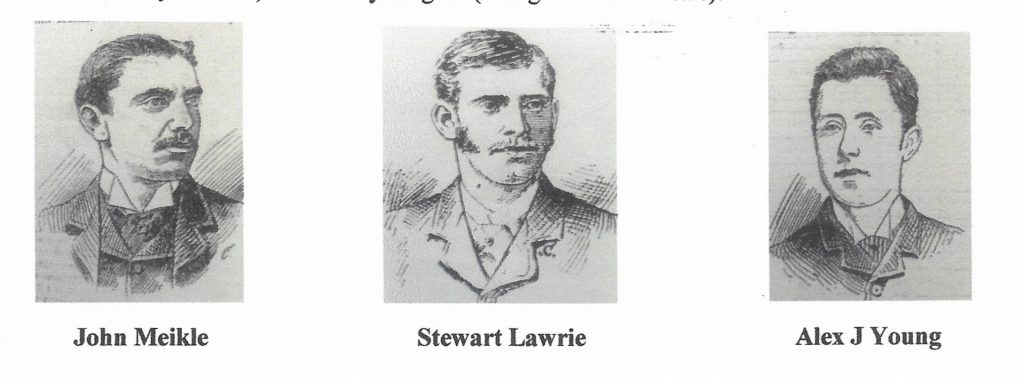

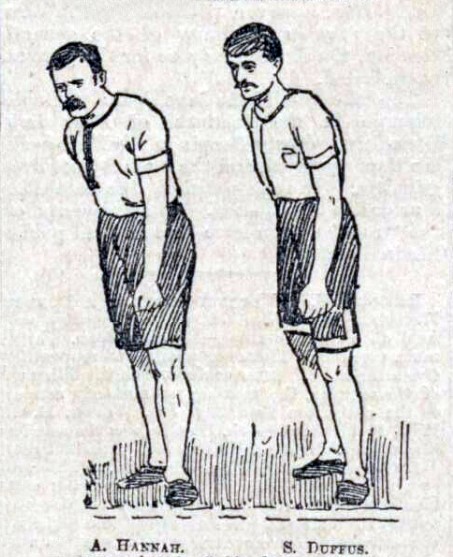

Andrew Hannah and Stewart Duffus were among William Robertson’s toughest opponents

To sum up, the 1895 season had marked Robertson’s entry into the vanguard of Scottish long-distance running. His versatility that year had been particularly impressive. Not even the great Andrew Hannah could boast such a range from the half mile to ten miles. He had also won his first S.A.A.U. championship with a performance which had left no doubt as to his supremacy in Scotland over the mile. Finally, he had come tantalisingly close to breaking the native mile record, which, it had to be assumed, was living on borrowed time.

After suffering a heavy defeat by Andrew Hannah in the Clydesdale Harriers’ seven-mile open handicap on 1 February 1896 Robertson was not among the hot favourites for the 11th running of the Ten Miles Cross-Country Championship of Scotland at Inverleith Park, Edinburgh, on 14 March. The week before the championship, Scottish Referee predicted he would only come seventh. In fact, he finished third behind Andrew Hannah, who won for the fifth time, and Stewart Duffus, who had moved to Glasgow with his brother and switched allegiance from Arbroath to Clydesdale. Disappointingly, there were only 24 participants and Clydesdale was the only club to finish a team.

The inaugural S.A.A.U. 10-Mile Championship at Hampden Park on 10 April looked to be following the script of the previous year’s event when it developed into a two-way battle between Hannah and Robertson. This time, however, the outcome was up in the air until the last mile, when Hannah broke away from Robertson and won by 15 seconds in 54:56.8. For Hannah, it was title #7, which we know in hindsight was a record that would never be surpassed. A new native record had been hoped for, but the weather gods had other plans. The runners had to battle not just with each other but also with the wind. The first mile was done in 5:03.6, the second in 10:20.6, third in 15:41.4, fourth 21:04.2, fifth 26:33.0, sixth 32:10.4, seventh 37:47.6, eighth 43:26.4 and ninth 49:16.2. The rival S.A.A.A. Championship, which was decided in Powderhall on 4 April, was won by Robert Hay (Edinburgh Harriers) in a slower time of 55:56.6, but Hay put in a very fast finish leaving a question mark over his true ability. A national championship ought ideally to provide a measure of transparency, but the divide within Scottish athletics had only muddied the waters and needed to be urgently addressed.

Robertson renewed his rivalry with Hannah and Duffus in the St. Mirren sports at Paisley on 25 April and finally turned the tables on his rivals by winning the three-mile handicap off scratch in 15:20.0. On 9 May, he faced his principal rivals again at Tynecastle. After winning the mile handicap off scratch in 4:34.6, he stripped again for the four-mile handicap. In a thrilling race which ended in a near blanket finish, Duffus (20:52.0) won from Hannah (20:52.3) and Robertson (20:52.4).

Robertson produced a string of good performances in the run-up to the season highlight. After winning a mile steeplechase at Celtic Park on 25 May in a fast 4:58.0, he also took the mile handicap at Hampden Park on 30 May in 4:35.4. In a three-mile inter-club race at Tynecastle on 6 June, he came home a close third behind Duffus and Hannah in 15:25. A 4:31.0 mile at Ibrox on 13 June showed that he was peaking just in time for the S.A.A.U. Championships at Hampden Park on 27 June.

Despite being the firm favourite, Robertson had great difficulty defending his title in the mile from Charlie McCracken. The young Carrick Harrier, winner of the Scottish Junior Cross-Country Championship, ran the race of his life and pushed Robertson to a new native record of 4:27.2. McCracken (4:27.6) was also inside the old figures that had stood to D.S. Duncan for eight long years.

His absence was not as noticeable at that year’s international match against Ireland in Dublin as it was in the previous year. In 1896, despite wins in the half mile and mile by the outstanding Hugh Welsh, as well as wins by Robert Hay (4 miles) Hugh Barr (long jump), the Scottish team was no match for the Irish in the sprints and technical events, and lost 7-4.

Not being able to represent his country, Robertson entered the Kirkcaldy F.C. Sports on 15 July and despite being heavily handicapped, won the mile from scratch in 4:34.0.

Even as the summer drew to a close, Robertson showed that he had husbanded his resources well, for he was not showing any of the typical signs of staleness one would expect of an athlete towards the end of the competitive season. On 10 August he lined up against the Irish champion Jack Mullen on the scratch mark in a two-mile handicap at the Celtic F.C. Sports. Keeping well together throughout, they overhauled the lesser runners in the field and made a race of it on home straight. Here, according to the Glasgow Herald, Mullen “shot to the front, and won amidst great enthusiasm by about five yards” in 9:44.6. Despite failing to win, Robertson had the satisfaction of improving his personal best to 9:45.5. Among the Scottish amateurs only Andrew Hannah (9:41.0) and Stewart Duffus (9:41.2) had ever gone faster over 2 miles at the time.

This was, incidentally, to be Mullen’s last race as an amateur. He was immediately suspended by the I.A.A.A. for competing at a meeting held under S.A.A.U. rules. Within a week he had accepted an offer from Celtic F.C. to train their players, while continuing to compete as a pro for a few more years.

Robertson concluded his track season on Monday 18 August by winning two-mile handicap at Hampden Park in 9:54.0. The gathering was for the benefit of Robert Hindle, the old pedestrian and latterly starter at most athletic meetings in the West of Scotland. In his heyday Hindle won Scottish and English championship at distances up to a mile. The great William Cummings, holder of professional world records at a mile and ten miles, was his protégé. Hindle, who was the groundsman and trainer to St. Mirren Football Club, died from bronchitis a few months later at his Paisley home at the age of 50.

1896 had again been another successful year for Robertson. He had achieved a third place in the S.C.C.U. Championship, a second place in the S.A.A.U. 10-Mile Championship and he had defended his one-mile title at the S.A.A.U. Championships. He had once again set several personal bests. After many heroic attempts, he had finally claimed the native mile record in the mile. What did the future hold for him? In 1897 he would be up against the prodigious young Watsonians Hugh Welsh and Jack Paterson; as well as Stewart Duffus, now the holder of the Scottish 4-mile record (20:10.8). On the other hand, Andrew Hannah had hung up his spikes for good. He was no longer an obstacle on the road to success, which was arguably more open than ever.

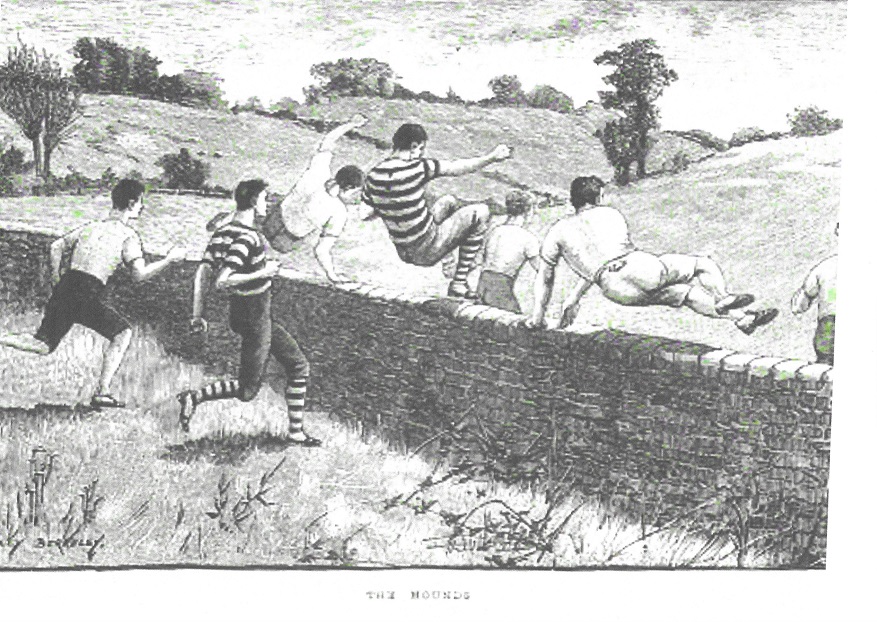

Robertson got his 1896/97 cross-country season off to a good start by winning the Clydesdale Harriers’ Open 7 Mile Scratch Handicap at Maryhill Barracks on 5 December 1896. This was the second running of the event, which incidentally was the first ever open cross-country race to be held in Scotland. Four months of twice weekly club runs later, and Robertson was being touted one of the favourites for the 1897 Senior Cross-Country Championship Underwood Park on 11 March. In fact, he finished second. In a gruelling battle of attrition over heavy terrain, Stewart Duffus was the first past the post in 1 hour 12 minutes, half a minute ahead of Robertson. However, the storyline behind the result is that Robertson had torn his “knickers” while crossing a barbed wire fence, forcing him to stop to change them and losing valuable time. In more fortunate circumstances the outcome may have been different.

The rift which had divided Scottish athletics for two seasons had been resolved during the winter, with the result that, once again, the Scottish amateur athletics clubs were unified under the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association.

The first track championship of the season was the 10 Miles Championship of Scotland for the £25 challenge cup at Hampden Park on 9 April. Both Robertson and Stewart Duffus were back in action with points to prove: Robertson keen to avenge his defeat in the cross-country championship, Duffus determined to validate his position. Robert Hay, the holder, was a notable absentee. The lack of entries suggested, according to Scottish Referee, “a paucity of long-distance men in Scotland”. The race practically resolved itself into a match between Duffus and Robertson, who alternated the lead at a moderate pace just inside standard time (57 min). On the last lap, Robertson showed his superior speed and pulled away from Duffus, who, seeing he had no chance, gave up with 220 yards to go. Robertson finished alone in 56:19.0 and celebrated his first national 10-mile title at third attempt. The splits were: 1 mile – 5:20.2; 2 miles – 10:53.2; 3 miles – 16:28.2; 4 miles – 22:15.6; 5 miles – 27:51.6; 6 miles – 33:39.6; 7 miles – 39:18.6; 8 miles – 44:56.0; 9 miles – 50:44.6.

A couple of low-key races set Robertson up nicely for an attack on the three-mile record in the Abercorn F.C. Sports at Underwood Park, Paisley, on 15 May. Starting at scratch alongside Stewart Duffus, Robertson romped home first in a native record of 14:57.2 and became the first Scottish amateur to run 3 miles in under 15 minutes. His arch-rival Duffus had not only fallen and retired but also lost both his official and unofficial records. In 1896 Duffus had run a 15:06.4 at the Rangers F.C. Sports on 1 August and an unratified 15:04.8 at Airdrie on 15 August.

On 12 June Robertson met the Watsonian Jack Paterson, one of the rising stars in Scottish athletics, for the first time in a 3-mile inter-club race at the Edinburgh Harriers Sports and won by 4 yards in 15:15.4 after outsprinting Paterson. Having previously been known as a staid front runner, he had somehow metamorphosed into a fast finisher.

Jack Paterson

A 2:01.6 p.b. off scratch in the half mile win at Parkhead on 22 June confirmed that Robertson was ready take on the dual champion Hugh Welsh in the S.A.A.A. mile championship at Celtic Park on 26 June. It was a tall order. The young Watsonian was a firm favourite after making an impressive debut at Cockermouth on 6 June, where he won the half mile in 1:58.0 off 10 yards and the mile in 4:24.0 off 15 yards. Scottish Referee reported that “W. Robertson is to do special training for championships, and may be seen in auld Ayr shortly.” Robertson knew he would need to do something special to beat Welsh. This, according to the Scotsman, is how the race went: “The S.A.A.U. champion went off at a brisk pace and for most of the way led Welsh by a few yards. At the bell, however, the Watsonian reduced the gap, and soon got ahead of his opponent. Entering the back straight he was in front, and gradually increasing the distance between himself and his only rival, he had the issue beyond all doubt coming into the straight for home. Robertson did not relax his efforts, but success was beyond his powers, and he was thoroughly beaten.” Welsh won by a clear 10 yards in a new Scottish record of 4:24.2 and Robertson also bettered the old figures with 4:26.0. The track had reportedly been showing signs of “lifting”, and it was reckoned that Welsh’s time was worth two seconds faster in perfect conditions. Having completely run himself out in the mile, Robertson was forced to make an early exit from the 4-mile event won by Jack Paterson in 21:10.0.

The brilliant Hugh Welsh, seen here winning the 1899 A.A.A. Mile Championship, was the finest miler Scotland had ever produced and the nemesis not only of Willie Robertson.

After defeating both Duffus and Paterson in a three-mile team race at Ibrox Park on 3 July, Robertson was selected to run the mile and four-mile events in the upcoming international match against Ireland at Powderhall on 17 July.

On his first international assignment he finished second in the mile behind Ireland’s James Finnegan in 4:34.0 but dropped out of the 4 miles after leading for the first 2 ½ miles. Without Hugh Welsh to carry the half mile and the mile, the Scottish team lost by 7 events to 4.

Despite losing his national mile title and record to Hugh Welsh in 1897, Robertson was still able to look back on his best season yet. Highlights included: second place in the Scottish Cross-Country Championship, first place in the S.A.A.A. 10 Mile Championship, second place over the mile in the match against Ireland and a Scottish three-mile record, as well as personal bests over the half mile and the mile.

Robertson began the 1898 season by taking another tilt at the national cross-country championship, which was held that year on 5 March at Musselburgh. It was his fifth try. He had improved from year to year – from seventh in 1894, fifth in 1895 and third in 1896 to second in 1897 – and was eager to win it. Taking the lead early on, he delivered another courageous performance, but once again had to settle for being runner-up, this time to Jack Paterson, who won by 60 yards. Thanks to good packing by, among others, the Duffus brothers, Jim and Stewart, and David Mill, the Clydesdale had no trouble retaining the team championship.

The months of winter training for the cross-country season naturally also stood him in good stead for the S.A.A.A. 10-Mile Championship at Powderhall on 15 April. Making light work of a wet and heavy track, Robertson turned his title defence into a procession and lapped the entire field, finishing in 55:10.8. One observer was of the opinion that he had never run better. His mile splits were: 5:02, 10:21.8, 15:53, 21:15.2, 26:49.4, 32:24, 38:02, 43:45.6 and 49:49.2, his last mile taking 5:21.6.

In the run-up to the national championships Robertson tested himself over various distances. In a meeting in Celtic Park on 16 May, he managed to get through no fewer than 42 runners to win the half mile handicap off scratch in 2:02.6.

Then he went over the mile in the Queen’s Park Sports at Hampden Park on 4 June. Scottish Referee reported, “The one mile flat invitation handicap brought out 17 competitors, including W. Robertson, Hamilton Yuille, les Freres Duffus, and J.C. McDonald. Robertson, off 20 yards, was actual scratch man, and, starting with his well-known stride, he gradually overcame the men in front of him, and long before the finish the race was his. His time was 4 min 25 3-5 sec, which, considering that he latterly had no one to pace him or shield him from the breeze, was excellent. Pity it was that Hugh Welsh could not accept the invite. He would have started off scratch, and the finish between him and Robertson would probably have been a rousing one.”

On 11 June he crossed swords with Jack Paterson in a two-mile scratch invitation race at Powderhall, but lost narrowly to the fast-finishing Watsonian in 9:50.4.

Despite his feat against Paterson, Robertson went into S.A.A.A. Championships at Hampden Park on 26 June full of confidence. He had entered the half mile, the mile and the four miles! Could he seriously have been considering the fabled, never-before-seen “triple”? It looked plausible at least. The biggest stumbling block, Hugh Welsh, was absent readying himself for the A.A.A. championships the following weekend. The biggest hurdle was the ever-dangerous Paterson in the four miles, the last event. After winning the half mile (2:02.0) and the mile (4:38.8) without much trouble, he toed the line again for the four miles. However, it was not to be, a sore foot forcing him to retire and relinquish the title once again to Paterson.

On 9 July Robertson competed again over the half mile in Kilmarnock. Starting from scratch, he won a close race from W.C. Gudgeon, Ayr, who pushed him to an outstanding time of 1:59.8, just two tenths of a second outside the native record held by Robert Langlands. He was only the second Scottish amateur ever to have broken the two minute barrier for the half mile. It wasn’t the only sub-two half mile in Scotland that day, though. The Englishman Alf Tysoe also achieved the feat in Edinburgh, where he lowered the Scottish record to 1:57.8.

In the International match against Ireland in Dublin on 16 July, Robertson, despite his sub-two credentials, had to settle for third in the 800 yards behind Hugh Welsh and Ireland’s Cyril Dickinson in 2:05.0. In the mile he allowed himself to be lapped by Welsh and paced the latter to a new Irish record of 4:21.6. It was a generous, if not dubious, gesture on Robertson’s part as Ireland’s Faussett was still in the race, albeit at least 50 yards behind.

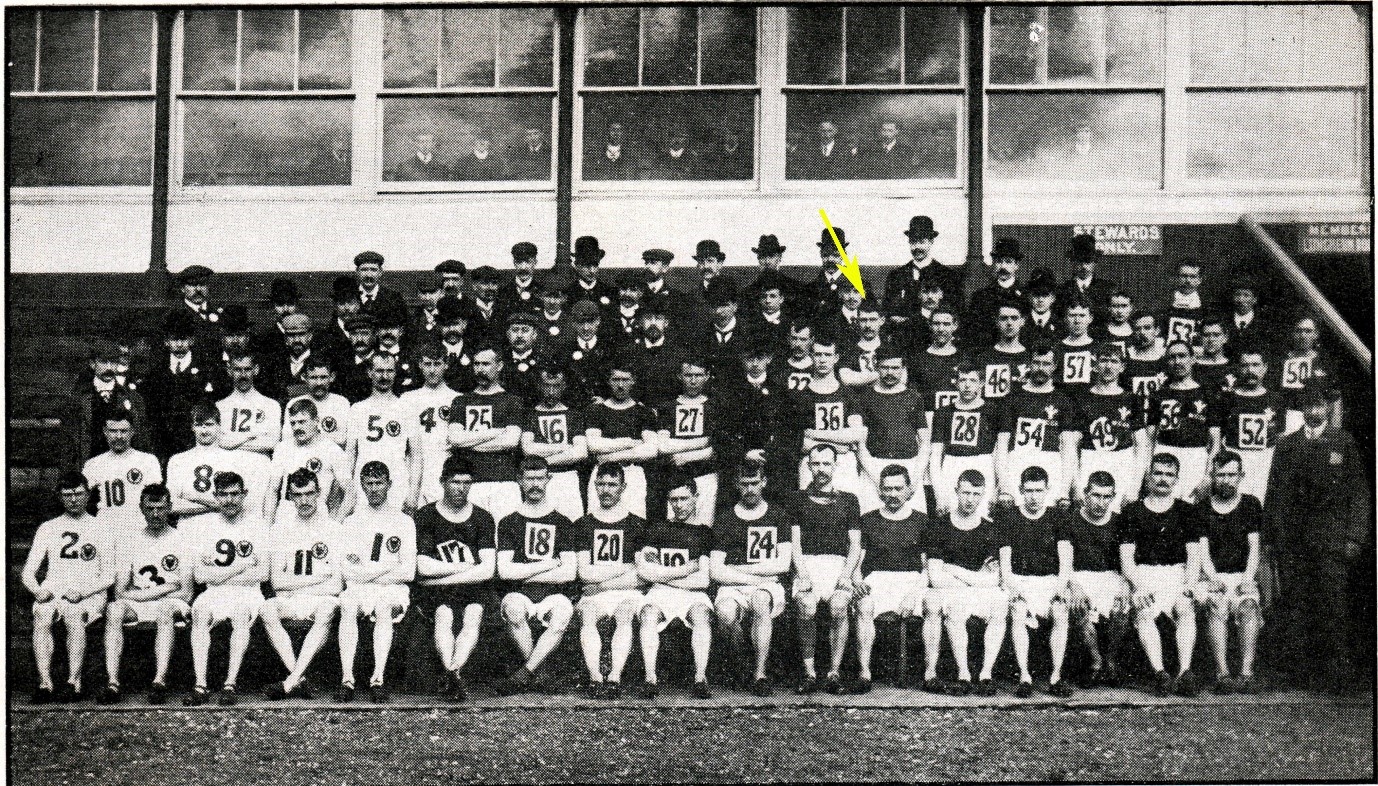

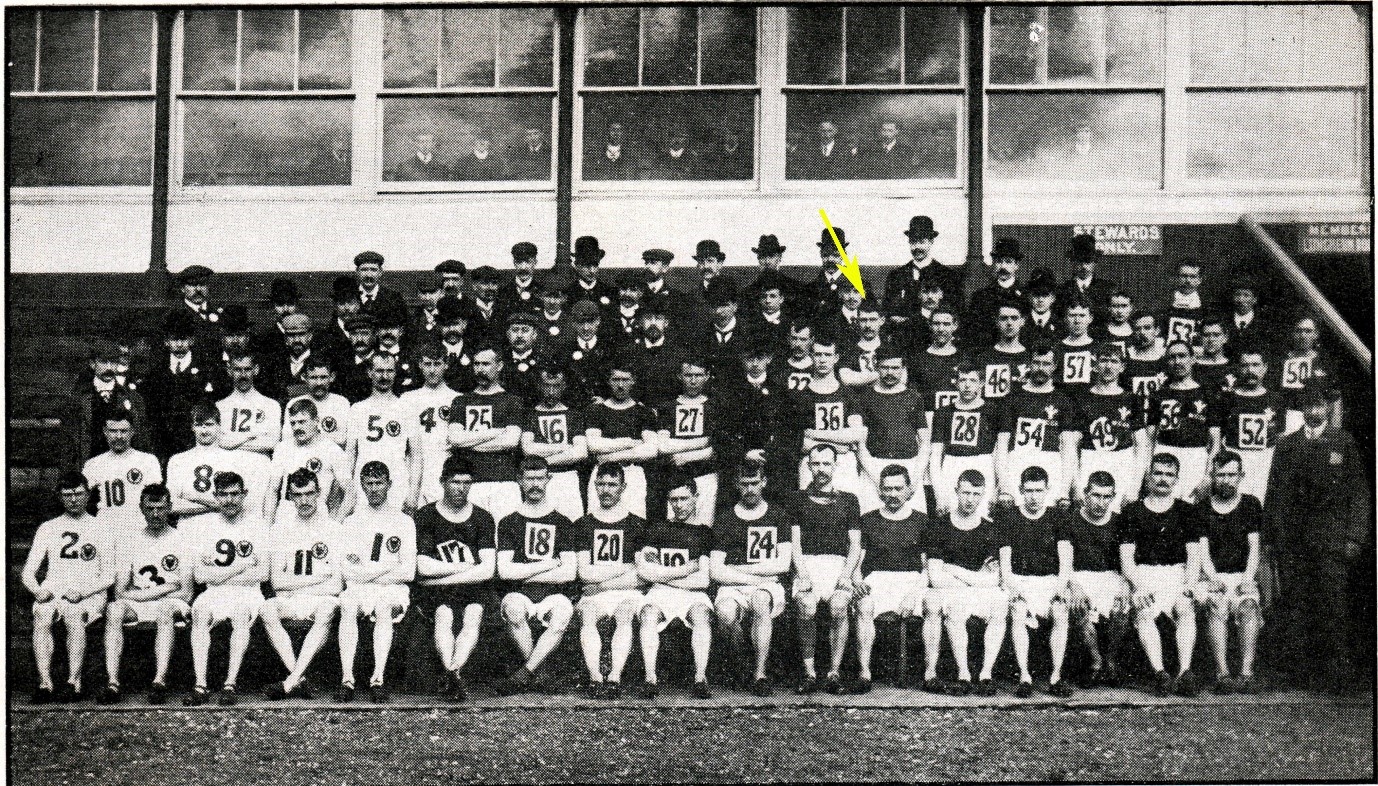

This group photo was taken during the 1898 Scotland v. Ireland match at the Ball’s Bridge Ground in Dublin. William Robertson is possibly the figure on the far left of the second seated row.

After winning a three-mile inter-club race at Berwick by a yard from the Duffus brothers in 15:12.4, Robertson finished his season with a string of indifferent performances suggesting staleness had set it. His last race of the year was at the Cliftonville Sports in Belfast on 13 August where he was unplaced in the mile handicap. However, this was to be a meeting that would come back to haunt him.

Shortly after the start of the winter cross-country season it transpired that the S.A.A.A. had set up a special subcommittee to investigate alleged professional activities by several well-known athletes. Following deliberations, it was announced on 28 December 1898 that Robertson as well as John and Stewart Duffus were to be suspended permanently for being implicated in the, quote, “personation of two amateurs by professionals at Belfast, and for betting”. Several other famous Scottish athletes, including the five-time S.A.A.A. half-mile champion Robert Mitchell (Clydesdale H.) and the 1894 S.A.A.A. mile champion James Rodger (Carrick H.), were likewise suspended for betting in conjunction with the meeting at Belfast.

The suspensions sent shockwaves through Scottish athletics. Particularly hard hit were the Clydesdale Harriers, who lost a number of high-calibre runners in one fell swoop. “Pace”, the athletics columnist for the Scottish Referee, wrote the following almost apologetic eulogy: “No matter what the Brothers Duffus and Willie Robertson have done on the track, and for which they have now suffered, they were shining lights in the world of cross-country running, and the determination shown by either of the trio has nerved young ‘uns to deeds over field and fen. Robertson was one of the best C.C. pedestrians I have known, and the manner in which he got over the ground in his awkward style was indeed marvellous. I should like to have seen Willie matched against Sid Robinson over a distance of ten miles, either over country or on the track.”

It was a harsh penalty for what many would have considered a minor infraction of the rules. Betting was, after all, a national sport. Scottish officialdom, however, saw otherwise.

Appeals were lodged and heard in May 1899 at a special meeting of the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association in Glasgow. It was reported that, “Mr. D. S. Duncan, secretary, read a report of the subcommittee giving the evidence which the appellants were suspended. The brothers Duffus and Robertson were called, and all admitted having taken part in the Cliftonville sports, where James McDermott (alias “Darwen”), of East Calder, a professional, who personated a Glasgow amateur named Stewart, was also a competitor. J.S. Duffus further admitted having congratulated Darwen on winning one of the events. The sports were held under amateur rules, but the appellants stated that betting was permitted to take place on the quiet.”

In the meantime, several papers had reported the arrest of McDermott for his role in the affair. “It is alleged,” the report read, “that McDermott did, on the 2nd August, 1898, at the sports of the Cliftonville Club, pretend that he was amateur, and did thereby obtain a gold watch and umbrella offered prizes by the club to bona-fide amateurs.”

Given such incriminating evidence, it goes without saying that all appeals were dismissed and the suspensions upheld. The banned athletes could not hold any office and could not coach or have any involvement in the sport thereafter. A permanent suspension was the death knell for an amateur sporting career. The Duffus brothers turned professional and spent the next years “making hay” at Highland gatherings. In 1912 Stewart Duffus emigrated to the USA to begin a new life. Robertson did not take the professional route like the Duffus brothers, although this would no doubt have been the easiest and most tempting one. As persona non grata in amateur circles, he could not be associated in any way whatsoever with the Clydesdale Harriers. There was, however, a loophole allowing him to lay the paper trail for the club’s pack runs during the winter months. Again and again he lodged appeals with the S.A.A.A.: again and again they were dismissed. Then, in early 1903, after four years in sporting oblivion, he was reinstated.

On 21 March 1903 the Scottish Referee reported: “Willie Robertson, the ex-distance champion of Scotland, who was suspended a few years ago, along with the Brothers Duffus, has been reinstated, and will represent his country in the forthcoming international. During the time he was suspended Robertson never took part in any professional races. The brothers Duffus did, and it is hardly likely they would be reinstated if wished.”

Robertson’s re-instatement came too late for him to run in the “national”. It was, therefore, something of a surprise when he was included in the Scottish team for the inaugural International Cross-Country Championship at Hamilton Park Racecourse on 28 March 1903. The Scottish Referee attempted to shed some light on this matter: “THE INCLUSION OF WILLIAM ROBERTSON will surprise not a few. He passed his re-instatement, however at the last committee meeting of the S.A.A.A., and has been in regular and well-worked training for some time past, and is said to be quite up to, if not, indeed, better, than his old form.”

What spoke for Robertson was certainly his successful track record in cross-country. However, his selection may also have had to do with the decision of the Scottish Cross-Country Champion Peter McCafferty to represent his home country Ireland, with the result that Scottish team was even more lacking in quality and depth than it already was. In the twilight of his career Robertson would once again have the chance to shine. Unfortunately, it was not to be. The strength-sapping eight-mile race was dominated by the English team led home by the indomitable Alf Shrubb. The home team only managed to finish third out of the four teams competing. James Crosbie was the first Scot home in 10th, followed by John Ranken 14th, James Ure 17th, Tom Hughes 21st, James Reston 22nd and Tom Mulrine 23rd. The Scottish champion McCafferty wound up 20th and was only the sixth counter for the Irish team. After four years in the wilderness and having been called up at short notice, it was perhaps no surprise that Robertson was a non-finisher.

The group photo was taken 15 minutes before the start of the inaugural I.C.C.U. championship at Hamilton Park Racecourse. The winner, Alf Shrubb, is seated at the front wearing #9. Most of the Scottish team is seated on the front right. Only three Scots are wearing race numbers. The yellow arrow indicates Willie Robertson, wearing #38.

The S.A.A.A. 10-mile championship was held just six days later at Ibrox Park. Of the 5 competitors, including Robertson, only Peter McCafferty made it to the finish. His winning time of 57:07.2 was one of the slowest since the inception of the championship in 1886 and not even enough for a standard medal. Another week of recuperation would certainly not have been a bad thing.

The remainder of the track season did not go particularly well for Robertson either, despite the fact that he was receiving starts. His best run of the season was probably his third-place finish in the mile handicap at Celtic Park on 13 June, where he posted a 4:25.0 for a mile less 76 yards. The scratch man in that race, Alf Shrubb, gave up but returned two days later to set a Scottish 4-mile record of 19:32.2. Robertson also figured prominently in the early stages of the S.A.A.A. 4-mile championship at Ibrox Park on 20 June but broke down and finished unplaced. New stars were in the ascendency now, most notably John McGough of the Bellahouston Harriers, who achieved the half mile, mile and 4 miles “triple” that had eluded Robertson five years earlier.

In the 1904 the Scottish Cross-Country Championship over the Glasgow Agricultural Showgrounds at Whiteinch, Robertson showed signs of a return to form by finishing 10th in a race won by the Watsonian John Ranken. This performance saw him nominated for the second running of the International Cross-Country Championship at Trent Bridge Ground, Nottingham, on 30 April. Again, the English team led by Alf Shrubb dominated the proceedings with all six counters finishing inside the first nine. The Scottish team led by John Ranken in 11th again had to settle for third place with Robertson outside the scoring six in 39th place.

Owing to his diminishing returns on the track, cross-country was where Robertson’s attention necessarily lay at this late stage in his career. In 1905 however he could only muster a 38th place in the Scottish Championships at the Scotstoun Show Grounds in Glasgow and was not nominated for the I.C.C.U. Championship in Dublin. Here the Scottish team took the second place thanks to good packing behind a sixth-place finish by Sam Stevenson.

A new generation of Scottish long-distance runners was now emerging as the old growth thinned out. The baton would be carried forth by John McGough, Tom Jack, John Ranken and Sam Stevenson et al.

The 1906 Scottish Cross-Country Championships at Scotstoun were to be Robertson’s last. The Clydesdale Harriers, led home by Sam Stevenson in first place, won the team championship for the first time in four years. In a fitting finale to a chequered career, Robertson finished 23rd and closed in the winning team.

That brings to a close the story of Willie Robertson, one of the prime movers in Scottish distance running during the 1890s. One could also call it the rise, fall and redemption of Willie Robertson. At the time of his retirement he one of only two men to have won national track titles at distances from the half mile to 10 miles. To this can be added two runner-up finishes and a third-place finish in the Scottish Cross-Country Championship. With six S.A.A.A. titles and two Scottish records to his name, he stands alongside Jack Paterson, Stewart Duffus and Hugh Welsh and Andrew Hannah as one of the pivotal figures of his day. The only blemish on his career, albeit a big one, was his permanent suspension for betting on a dodgy race in Belfast. Fortunately for his persistence he was able to make a comeback in 1903 and represent his country in the historic inaugural running of what is today known as the World Athletics Cross Country Championships.

Main accomplishments:

Scottish Junior Cross Country Champion, 1894.

Scottish mile record holder, 1896-1897.

Scottish three-mile record holder, 1897-1904.

Half-mile Champion of Scotland, 1898.

One-mile Champion of Scotland, 1895, 1896 (S.A.A.U.) & 1898.

Ten-mile Champion of Scotland, 1897 & 1898.

6x the bridesmaid!

Robertson was also 2nd in the Scottish Senior Cross Country Championship in 1897 and 1898, and 3rd in 1896. He also finished 2nd in the S.A.A.A. 1-mile championship in 1897, 2nd in the S.A.A.A. 4-mile championship in 1893, and 2nd in the S.A.A.A. 10-mile championship in 1895 and 1896.

Personal bests

| Half mile |

1:59.8 |

Kilmarnock 09.07.1898 |

| Mile |

4:26.01) |

Celtic Park, Glasgow, 26.06.1897 |

| 2 miles |

9:45.51) |

Celtic Park, Glasgow, 10.08.1896 |

| 3 miles |

14:57.2 |

Underwood Park, Paisley, 15.05.1897 |

| 4 miles |

20:47.81) |

Hampden Park, Glasgow, 12.04.1895 |

| 10 miles |

54:07.0 |

Hampden Park, Glasgow, 12.04.1895 |

Thanks to Kevin Kelly and Hamish Thompson