William Mabson Gabriel

Edinburgh Harriers

William Gabriel had a short but impressive athletic career. Born in what is now Cumbria, he was a medical student at the University of Edinburgh in the very early 1880s. He ran for both Edinburgh University (his first choice on track) and Edinburgh Harriers and in addition to setting a Scottish record for 3 miles, he was also a ‘counter’ in both the Edinburgh Harriers Teams of 1886 and 1887 that won the Scottish Cross-Country Championships narrowly missing out on an individual medal by placing 4th in both races. He served as both Captain of the Club and as Club President.

William was born in Cumbria to Edward and Mary Gabriel in early January 1861 (birth registered in January). His father, originally from Bristol, was a ‘Perpetual Curate of the Church of England’ at St George’s Church, Kendal although living at Rockcliffe near Carlisle. There is some indication that his mother may have had a sight impairment from the census of 1881. He had a sister Fanny aged 3 in 1861 and a brother Ernest aged 2 in the same census year, while William is listed as 4 months (thus very early January 1861 as a birth month). They employed one nurse and two servants. Later in the 1881 census there is no longer a record of Ernest but there is a sister Ruth aged 17 in 1881 and William is listed as a Medical Student aged 20. This is in line with other records where he is listed as a doctor. There is, as yet, no record of when he matriculated at the University of Edinburgh, but the indication is that it is likely that he was in and around Edinburgh 1880 and 1881. There has been no research as yet within the university archives as to when he enrolled and when he graduated but there are records of him competing until 1887. There are no records of where he went to school. The first of his athletics experiences are recorded in 1881 aged 21 running in the One mile flat handicap and winning at the Ulster Cricket Club Athletic Sports. He also ran in the 2 miles against the legendary Snook. This would indicate some experience of athletics while still at school and also indicate a life style that allowed him to travel for meetings. 1881 would probably have been at the end of his first year as an undergraduate. His athletic career is summarised at the end of this piece. He appeared to return home at the end of July each year and played cricket.

WMG had his most productive period athletically from 1885 to 1887 as a founding member of Edinburgh Harriers in 1885, 1st captain of the club and running as part of the winning EH team at the first Scottish Cross-Country Championships in 1886. During the next cross-country season, he was again a counting member of the winning team at the second cross-country championships in 1887 and also set a Scottish 3 mile record on the track in May, 1887 at the Edinburgh Harriers Sports. He was President of the club in 1886-1887 and remained on the committee for season 1887-1888 despite not appearing to take any further practical interest in the club.

His only and perhaps peculiar contribution politically (apart from his presence on the Cross-country Championship Organising Committee for 1887) was his intervention as President of EH at what can only be described as stereotypically bad behaviour of the medical students of the club, when they disrupted a theatre performance at the Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh in a fit of pique:

After leaving Edinburgh around 1887/1888, William took up residence near Carlisle where he married Mary Collinson Tully from Kirkandrews-on-Eden (only a few miles from Rockcliffe) aged 30 in July, 1889. Mary’s father was a Sea Captain so was brought up mainly by her mother.

William and his wife appear in the census of 1891 as living in Keighley aged 40 with one servant and described as a Physician and Surgeon. Mary dies in 1902 and William remarries in 1903 and then all record of him is lost until the death of a WM Gabriel, is reported in Kent in January, 1940 aged 79. It may well be that he emigrated for a period of time, but it is also clear that there is no further record of him connected to the sport after 1888. In the same way that he suddenly appears as an athlete at 21 without seemingly any athletic record, he steps away just as abruptly at 28. It appears that he had no children by either wife.

Athletics career summary

William Mabson Gabriel and the Formation of Edinburgh Harriers and Cross-Country Season 1885-1886

David Scott Duncan called a meeting n the 29th of September, 1885 to form a harrier club for Edinburgh. However, St Georges’s FC had also called a meeting for the 30th at the Richmond Hotel, Edinburgh so at the meeting of the 29th it was decided to attend the meeting of the 30th. Attendance at the meeting of the 29th was essentially between University men and other interested parties while the one on the 30th was from the football club plus those of the 29th. Both parties came together on the 30th with a decision to form the Edinburgh Harriers. William M Gabriel was one of those present. At a further meeting on Monday 5th October, office bearers were appointed and WM Gabriel was appointed the first Captain of the club. Some 100 plus names had been enrolled.

The first run was on the 17th October from the Harp Hotel, Corstorphine with WMG acting as ‘pace’ over 6miles with a half mile run in with WMG coming 2nd in the run in to DSD. Their second run was from the Morningside Volunteer Arms over 8mls (72mins) with WMG in the pack. The 3rd run was diverted from Musselburgh to Mrs Crosbie’s Inn, Levenhall, soon to be a favourite, with 13 runners and WMG in the ‘fast pack’ (Fowside Castle, Tranent to Haddington), 7.5mls. The following week (4th run) was from The Sheep head at Duddingston with 33 runners and WMG as one of the hares. An account records that one of the hares had ‘fallen lame’ and was caught half a mile from home ‘but the other just saved his skin by half a minute’. The 5th run was from Justinlees Inn at Eskbank with 14 members over 8mls and was through the grounds of the Marquis of Lothian’s Estate.

By now the club felt confident enough to have a ‘competition’ and on 21st November there was a 2 mile handicap at the Royal Gymnasium. There is no record of Gabriel in the first three so if he was present it is likely he was ‘handicapped out of it’.

The first inter-club run between two Scottish Harriers clubs was on Saturday 28th November at Corstorphine, 8 from Clydesdale Harriers and 22 from Edinburgh over 10 miles. It was on a ‘hares and hounds’ basis with ‘jumps’ but the trail was lost. A further run on 12th December from the Railway Inn at Colinton was followed by the club cross-country handicap at Musselburgh on 19th with HH Almond of Loretto as judge. WMG along with DSD were off scratch so effectively handicapped out. The final run on 26th December was poorly attended with a note that ‘the bulk of the members are out of town’.

1886 started with a ‘smoker’ at ‘headquarters’ at which 60 were present and a run from Mrs Clark’s Inn, Coltbridge on the 9th of January, but no mention of WMG. Although entered for the Club’s 5 miles cross-country handicap and given 30 secs, only 17 out of the 24 entrants turned out and no mention of WMG although he may have run if entered as a captain’s duty. WMG turned out for the run from Mrs Crosbie’s at Levenhall on the 23rd of January.

It is also likely that he ran in the return inter-club at Ibrox with Clydesdale Harriers from the Northern Cricket Club Pavillion, Ibrox but again, no mention. 14 runners from Clydesdale and 13 from Edinburgh ran plus 5 from Lanarkshire Bicycle Club Harriers over 7.5mls. There is no further mention of WMG at the run from the Sheep Head, Duddingston on 6th February or of any run on the 13th February. However, the club 10 mile championship was run on 20th February at Musselburgh. On the day, 8 competitors out of just over 20 lost the course so the race was declared void and while WMG ran, he seemed to have been handicapped out again. The team for the Scottish Championships was announced and WMG was part of that team. In the re-run on 27th February, WMG placed 6th after the handicap was applied in 1hr, 1min and 43secs.

The Scottish Cross-Country Championships were held at Lanark on 27th March after a postponement due to weather (snow) from the 13th. WMG came in 4th and was third counter behind Duncan and Jack in the Edinburgh winning team. He was almost 3 minutes behind Finlay the winner and 1minute, 30 secs behind Jack in 3rd place.

Gabriel turned out for some 13-15 runs over the cross-country season of 1885- 1886 for Edinburgh Harriers, placed 4th in the National championship and was a counter in the winning team.

Cross-Country Season 1886-1887

Edinburgh Harriers has some 21 cross-country fixtures for the season commencing on Saturday 23rd October, 1886. It is unclear whether WMG took part in either the first one at Coltbridge or the second run mid-week at Corstorphine on Thursday 28th. He was not named in any further calendar run until 26th February, 1887 when he was listed as having a 2min handicap for the club’s 10 mile cross country championship but WMG was unplaced. Prior to this however WMG was asked to serve on the Committee of Management regarding the cross-country championships for 1887. This committee was elected at a meeting immediately following the inter club with CH on December 11th at a meal at the Bridge Street Railway Hotel following the run. It is unclear whether WMG was present or had allowed his name to go forward. This was the meeting that decided on 3 qualifying runs by members in order to be selected for the championships (controversially CH would later visit Ayr with one member and declare it a CH run in order to be able to select Ayr runners).

Following his appearance at the club 10 mile cross-country champs in February 1887, WMG again appeared in a club run from Granton on 12th March while being named in the EH team for the Scottish Championships which took place on Saturday, 19th March at Hampden Park. His runs immediately prior to the championships seemingly an attempt to get his 3 counting runs in order to be eligible for selection. WMG came in 4th in the championships and was second counter for the EH team that retained the team championship. It would appear from his absence during the cross-country season that he had either graduated and was working elsewhere or that he had incurred an injury and couldn’t run, but if the latter was the case then his run in the Scottish Championships was extraordinary. He had also given up the Captaincy of the club to take on the Presidency for season 1886/1887, a role which would indicate less onerous attendance. Out of all the runs of the season he managed about 3-4 appearances but had clearly maintained a degree of fitness. At the club AGM in October, 1887, he stepped down from the Presidency of the club and allowed his name to be put forward for the committee for 1887-1888 but there are no further reports of him.

Athletics career summary – Track

1881

Ulster Cricket Club Athletic Sports, 18th April, 1881: One mile flat h’cap, 1st winning a gilt oxidised jug. Also competed against Snook in the 2 miles off 180yds.

West of Scotland Sports Hamilton Crescent, 16th April, 1881: 880 yds collided with a competitor when ‘going well’.

Queens College Athletic Sports, 14th May, 1881: 880yds flat open h’cap – unplaced off 15yds

Edinburgh Royal High School Sports, 21st May, 1881: 880 h’cap for recognised clubs, 2nd off 15yds EUAC.

Arthurlie Sports at Barrhead, 25th June, 1881: One mile – going well but mistook the number of laps.

Edinburgh University Athletic Club Sports at Corstorphine, 2nd July, 1881: Two miles Open h’cap – 1st off 110yds. 11mins

Edinburgh Football Association Sports at Tynecastle, 11th July, 1881: 1st – 880 yds and 1st – One mile.

Buccleuch Cricket Club Sports at Granton, 16th July, 1881: 1st One mile h’cap beating David Scott Duncan.

Played cricket mid-August, 1881, Burgh v Silloth

1882

Heart of Midlothian Sports, Edinburgh, 6th May, 1882: 880 yds Open. 1st

Watsonians Sports at Myreside, 13th May, 1882: 880yds h’cap – not placed off 7yds. ‘Not in good form’.

Edinburgh Institute Games at Warriston Park, 17th June, 1882: Open 880 yds WMG off 12yds – not placed.

Edinburgh University Bicycle Club Sports at Powderhall, 24th June, 1882: 880yds h’cap Open. 2nd off 20yds

Edinburgh University Athletic Club Sports, at Corstorphine 1st July, 1882: One Mile flat, 2nd beating David Scott Duncan into 3rd and 2 mile, Flat, h’cap, Open – 3rd (thronged with young ladies!)

1883

Glasgow Academicals Sports at Kelvinside, 5th May, 1883: 2nd Steeplechase, Open

Scottish Amateur Athletic Association Champs. at Powderhall, 23rd June, 1883: One Mile, 2nd to DS Duncan

Edinburgh University Athletic Club Sports at Powderhall, 7th July, 1883: One Mile Flat, 2nd to DS Duncan. Time $mins 30 4/5.

1884

St Andrews University Sports at St Andrews, 29th March, 1884: 2nd – 880yds (Universities).

Scottish Amateur Athletic Association Champs. at Powderhall, 28th June, 1884: Unplaced in both 880yds and One mile (dropped out).

Edinburgh University Cycling Club Sports at University Cricket club, 5th July, 1884: 2nd One Mile h’cap off 15yds

Edinburgh University Athletic Club Sports at Powderhall, 12th July, 1884: 2nd off scratch, 2mls h’cap, Open. WMG time for 1st mile was 4. 58. He threw up at the finish!

1885

Scottish Amateur Athletic Association Champs. at St Mirren FC, Paisley, 27th June, 1885: Entered mile but didn’t run. 5,000 spectators

No further indication of him on the track under EUAC and didn’t compete in the EUAC Sports – left University?

1886

Edinburgh Harriers/Liverpool Harriers Inter-club Track Meeting at Powderhall, 1st May, 1886: 2nd in the One mile, started 4mls but dropped out

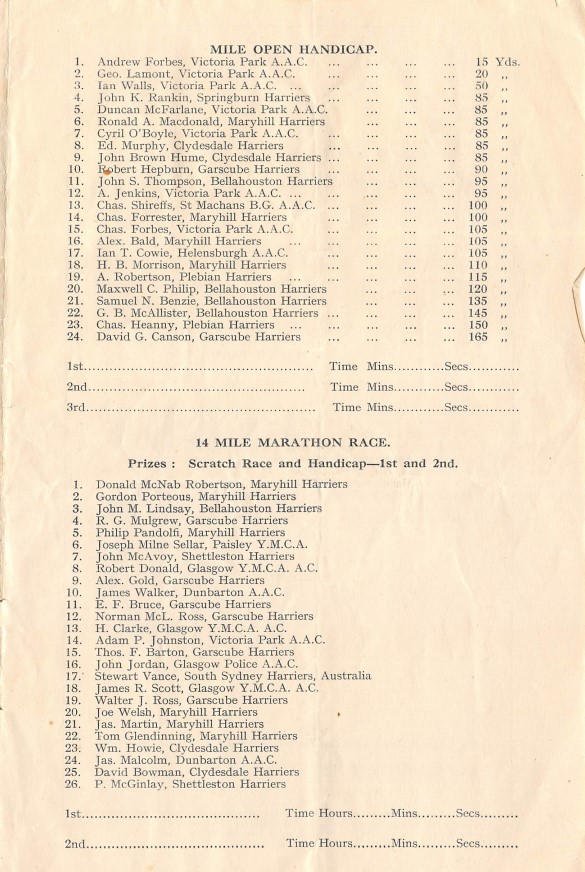

Vale of Leven Sports at Alexandria, 8th May, 1886: 880yds Open h’cap – 2nd off scratch; One mile Open h’cap – 1st off scratch

Trial Races for International Cycle Tournament at Powderhall, 12th May 1886: 2nd – 880yds off 18yds (one foot race on programme)

Edinburgh Northern Bicycle Club Annual Sports at Powderhall, 15th May, 1886: 2nd – One Mile h’cap off scratch to WM Jack off 75yds.

Edinburgh Institution Games at Warriston, 21st May, 1886: 1st – 880yds Open h’cap off 16yds. Time of 2mins 8secs

1st Edinburgh Harriers Annual Sports at Powderhall, 29th May, 1886: One Mile – scratched, 1st 4mls Invitation race & winner of the McKay, Cunningham & Co Cup. 5min first lap, 10min 28secs, 16mins 2 secs and 21mins 16 3/5ths. Cup worth 15 guineas. Beat AP Finlay. Cup a tankard with figures in relief, oxidised and gilt. WMG described as ‘dead beat when finished’.

Dunfermline Cricket & Football Club Sports at Lady’s Mill Park, 5th June, 1886: 1st – 880 yds off scratch in 2mins 10secs; 2nd – One mile h’cap off scratch to winner off 60yds

Hull Athletic Club Sports at Botanic Gardens, 14th June, 1886: 880yds DNF off scratch; 3rd – One mile h’cap off scratch

Scottish Amateur Athletic Association Championships at Powderhall, 26th & 28th June, 1886: 2nd One mile (only2 entrants) and dropped out of 10 miles after 4.5 mls.

WMG seemed to return home in July and August as he is reported as playing cricket. He turned out for a select XI (Mr Blakes Team XI) against Scotby and was bowled for 5.

1887

The Ulster Cricket Club Sports, 8th April, 1887: 1st in the 2 miles h’cap off 220 yards.

Edinburgh Northern Cycle Club Sports at Powderhall, 14th May, 1887: 5th One mile open h’cap off 30yds

Edinburgh Harriers 2nd Annual Sports at Powderhall, 28th May, 1887: 1st – Invitation 3mile flat race. 1st – 15mins. 37 2/5th secs. 6 runners. Scottish 3 mile Record (ratified in February, 1888)

Scottish Amateur Athletic Association Championships at Hampden Park, 25th June, 1887: 3rd in 4mls, unplaced/did not run in 10 miles

St George’s FC Sports at Powderhall, 30th June, 1887: One mile h’cap off 65 yds

St Bernard’s FC Athletic Sports, 16th July, 1887: 1st One mile flat h’cap – no record of him running (off 45yds)

Templepatrick Amateur Athletic Meeting, Ireland, 23rd July, 1887: 880yds Open flat race h’cap unplaced off 20yds; One mile open flat race h’cap – unplaced off 50yds

Edinburgh Harriers Prize list for 1887: Gabriel: 1st – 3; 2nd – 1 and 3rd – 2.

1888.

There is no further record of WMG either in athletics or in cricket

HMcDT9/2/2021