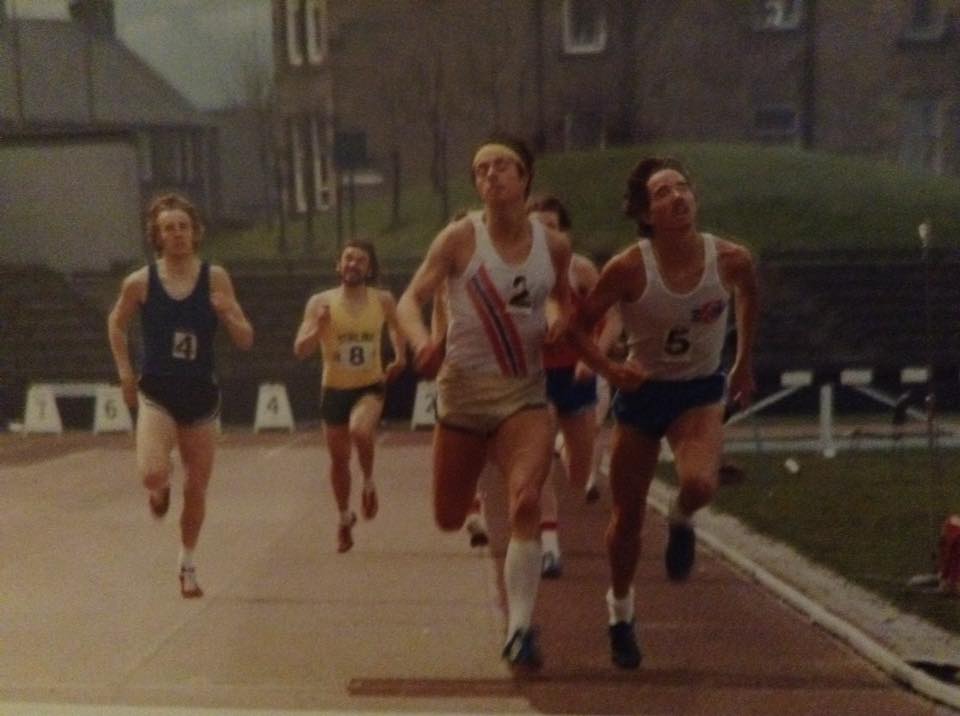

Peter Hoffmann leading Paul Forbes in a Training Session at Meadowbank.

Wish upon a star

‘…Questions unanswered

Questions not asked

Some are worth knowing

Some left in the past

Go in with eyes open

Your life will be grand

Just give it your damndest

And go lead the band…’

Roger Turner

Forty years ago I ran a half mile in 1 minute 46 seconds, still a respectable performance today. At one time I even had an ambition to have raced Coe and Ovett down the home straight in the race of the century at the 1980 Olympic Games 800 metres final in Moscow.

Most runners look back on their careers feeling they never quite fulfilled their potential. As the old saw goes if is the saddest word in the English language. If only I had…Like many of you out there, from a distance of forty years I discern many good patterns of what we did well, but also some key mistakes too, which of course tear at the soul. And talking of souls, Father Gianni in the recent BBC series set in Tuscanny, Second Chance Summer, expressed it rather beautifully when he said: ‘…the problem is you only learn with age and experience, so by the time you realise you have learnt a lot of things unfortunately a lot of time has passed and many chances have been lost.’

But for others-today’s and tomorrow’s young athletes it is not too late. Ben Jones, M.D. said ‘The saddest thing about dying is that all the stuff you’ve learned goes in to the ground with you. Make sure you pass it on before you croak.’ Following Ben’s advice, here’s my starter for ten.

But first, a health warning. I’m neither a coach; nor a sports scientist; nor an academic, but instead someone who has run for almost 60 years – a reflective practitioner. This is not an academic nor a scientific treatise which works back from the demands of the event, relating them to your strengths and weaknesses and accordingly tailors a training programme, based on lactate tolerance or VO2 levels etc. Instead, it offers some practical, simple, common-sense tips garnered from a lifetime’s running experience from beginner, to international, to fun runner. I’m advocating a simple approach, but one which I sincerely believe will help any half miler run a best performance. I’m targeting it at international class athletes, but it’s equally applicable to aspiring youngsters wishing to run a great half mile or any master’s athlete out there too-just apply the principles and alter the times.

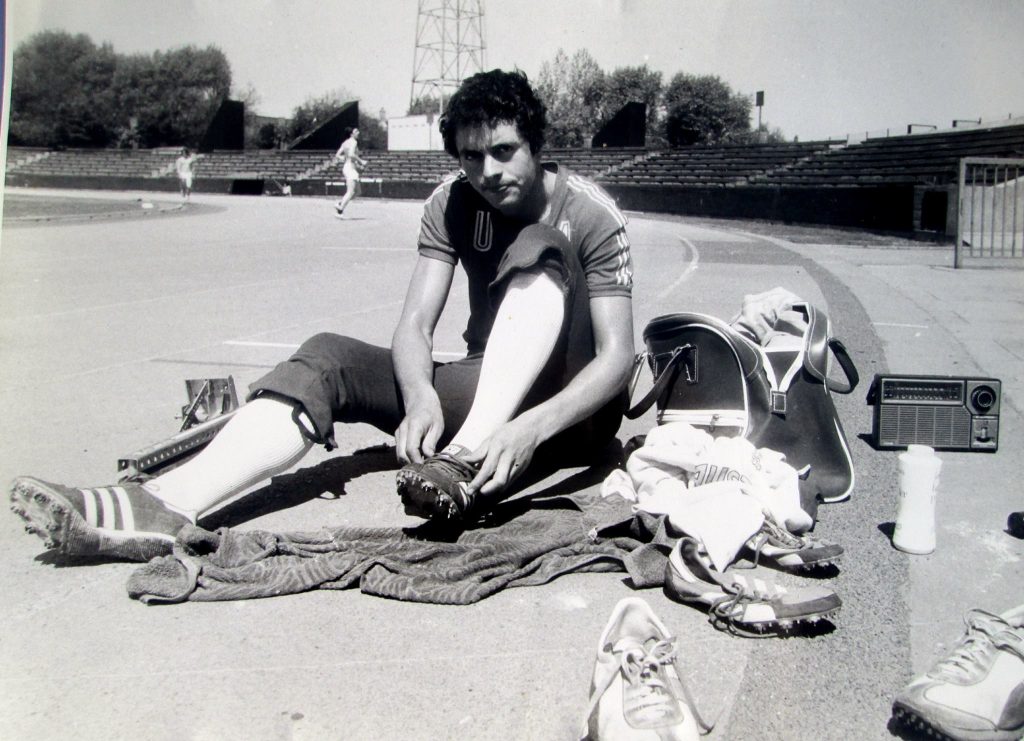

Peter preparing for a Track Session

- Dream Baby, Dream

In the 1920s, the writer and mythologist, Joseph Campbell (who also happened to be one of America’s finest half milers) wrote of following your bliss:

If you do follow your bliss, you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while waiting for you, and the life you ought to be living is the one you are living. When you can see that, you begin to meet people who are in the field of your bliss, and they open the doors to you. I say, follow your bliss and don’t be afraid, and doors will open where you didn’t know they were going to be. If you follow your bliss, doors will open for you that wouldn’t have opened for anyone else.

You need to have a dream to sustain you over the years; find out what motivates you to get out there season in, season out, to train in all weathers. Find your dream, then follow it; and remember Festina lente – Make haste, slowly.

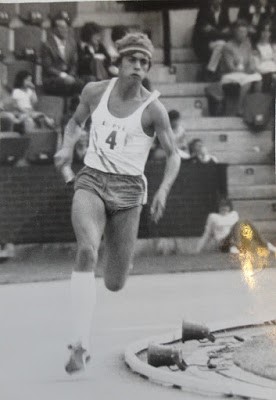

Peter in a 200m race: note the GB vest

- Control Your Weight

Ensure your weight is at its ideal level. If it’s not, you won’t fulfil your potential. Simple fact. But that doesn’t mean being as light as possible. Too often I see good international runners who are actually too light. Don’t sacrifice lightness for strength. Instead, what you’re really after is the optimum power to weight ratio. So it’s better to be two or three pounds heavier with good power than to be too light with little power. The best athletes glide effortlessly over the track. Think Ovett at his peak over 1500 metres at the 1977 World Cup.

Control and monitor your weight; if you need to lose anything, do so, but very slowly. Be patient. If you’ve gained weight you will have done so over a period of time. To lose it, do so similarly. A pound a week is aplenty and you will hardly notice the effort; yet over 6 months that would add up to almost two stones! Eat regular, balanced, healthy tiffins every few hours. Drink plenty of water. Most people know what they should be doing. At the end of the day, retire to bed in the evening knowing that when you awake the following morning you will be very, very slightly lighter.

Peter and Paul Forbes

- Practice Running FAST!

By running fast, I mean sprinting flat out several times each week. Be honest with yourself-when did you last sprint as fast as you could, putting the pedal flat to the floor? For most athletes it will be months-probably years! Unless you’re a 60 metres indoors specialist or a 100 metres sprinter, 99% of runners never practice running flat out, so how can you expect to suddenly turn on the turbo-jets come a race, especially if it’s a year on from the previous summer? So, incorporate sessions over 30-50 metres several times each week e.g. 2 x 4 x 30 metres with a good recovery. And that’s just to maintain your speed. By the time you get into your early 20s your performance will deteriorate. Incorporating pure sprints into your training programme will help make the key middle distance sessions easier andswifter too.

- Strength and Power

But better still, rather than just maintaining speed, let’s improve it by improving your power. Get in to the gym twice a week. Do plyometrics; weights; gym work and bounding. In the off season run fast 20 seconds hill repetitions up a slight incline wearing a weights jacket. Do a Togher body weight circuit or get along to a Metafit session which is also a valuable cardio workout too. Work your glutes. Do squats. Do step-ups. If time is scarce run a few sprints followed by your strength work; it makes for good sense. Develop a strong core-everything comes from there. Buy a pair of 1lb barbells and practice fast arm action in front of the mirror for 2 minutes each evening.

But, on top of that here’s something different. Many athletes’ performances tail off toward the end of the season. Commentators say this is due to tiredness or getting stale and lacking motivation. I believe it’s more to do with the fact that after the spring most athletes neglect strength-work through the summer months. A radical proposal-keep the strength-work going throughout the track season. In 1984 Coe was still in the gym a week before the Los Angeles Olympics. Similarly, Salazar likes to see Farah et al keep that snap going throughout the racing season. You won’t need to do so many repetitions-just do enough to maintain your power to weight ratio; and perhaps ease off altogether ten days before your main competition of the season.

- Cardiovascular System

To run a good half mile you need a reasonable aerobic base; equally importantly, you need to be fit enough to undertake the key middle distance track sessions. I recommend doing a steady run every third day. But you will end up supplementing this when you warm up and warm down for your track and gym sessions on other days adding another half hour of daily aerobic running. Every couple of weeks incorporate into your schedule a long, steady run of between 60 and 90 minutes. If a 5k Parkrun happens to fall on such a day, give it a go-it will give you a useful base line as well as motivating you to run fast and hard on occasion. But quality and speed and tiredness should never be sacrificed at the altar of high mileage. There’s a trade-off and that needs to be in favour of track work and gym. If high mileage was the key to running fast half miles then all those millions of runners churning out 70 mpw would be running them. Generally, they don’t. And when they do, it’s the exception that proves the rule.

6. Box Clever

There are lots of little maxims out there; some of them are wise. Amongst them, less is more, is excellent advice. The Greeks had a word for it-practice the golden mean-nothing in excess, everything in moderation. Train only once a day and rest up for 24 hours before your next session. It will prevent injuries in the long term; help you recover from the previous day; and equally importantly you’ll have a zest for the next session. Similarly, it’s better to under-train than to over train.

Try to always run with the wind-practice running quickly and with good technique. And talking technique, if you don’t have it, identify with someone who does and copy them. El Guerrouj was the most beautiful runner; as is Bernard Lagat.

It’s still useful to have heroes; adopt a phenomenological approach; identify with someone you admire and respect and when those key moments of choice come along, ask yourself how they might behave or react in this situation. What would they do?

Closer to home, find a good mentor. When my good friend Paul Forbes (a 1 minute 45 seconds half miler) and I were teenagers we trained regularly with Adrian Weatherhead, a sub 4 minute miler. He was a decade older and taught us much, mainly informally, often when we were warming up or warming down after a session.

Get into a good training environment and squad. Training should be hard, but fun. Try to run sessions where sometimes you’re the top dog-it’s good to be confident and to reinforce this attribute; on other occasions run with peers to introduce a little bit of competition and edge; and occasionally train with people who are better than you at some sessions-but not too often, as you want to be a very positive athlete and racer. But such sessions will help push you and take you out of your comfort zone. At weekends we had the best training squad in the world featuring World number 1 David Jenkins; World Student Games silver medallist, Roger Jenkins; 8 Nations gold medallist, Paul Forbes; GB international, Norman Gregor; sub 4 minute miler, Adrian Weatherhead; as well as myself, an Olympian and European Junior silver medallist. It meant that if we were running 6 x 500 metres, each athlete would take one run from the front, with Adrian on the last rep. It meant for a much higher quality session than we could have managed alone. But, it was important to get away from that elite squad at other times to prevent burning ourselves out.

Listen to your body. What is it telling you? Athletes tread a fine line-it’s like being a tightrope walker, making continuous fine adjustments to achieve that elusive balance between two polarities-being honest with yourself and staying disciplined-getting out there and just doing it, but also being sensible and taking the occasional day off too when you’re feeling exhausted or coming down with a cold.; as mentioned above, it’s always better to under train than to over train.

And as in all important areas of life, prioritise. You only have so much energy and those aspects of training that are most important should never be at the mercy of those areas which are less so. Distribute your energy as if it’s gold and allocate it wisely. Be at your freshest and at your very best for the key middle distance track sessions of the week. Make sure you’re turning up for these sessions with an eagerness-with an appetite-you’re excited and slightly nervous and apprehensive and not knackered, tired or unenthusiastic, where you end up just going through the motions. In other words don’t sacrifice quality for quantity. And talking of quality here’s some radical advice-simulate half mile racing-regularly.

7. Simulate 800 metres running-regularly

That begs the question what do I mean by quality. Similar to athletes ignoring sprinting flat out, most half milers only ever run occasional flat out 600s throughout the year; perhaps on fewer occasions than on the fingers of one hand, usually in the late spring. And yet this is what they’re expecting their bodies to do in a race! It’s crazy. Get your body used to doing what it’s expected to do come race time. Surely, it’s common-sense to practise this key aspect much, much more regularly so that you not only do you get used to running like this, but so that you become better too?

Each new season you hope to improve on what you’ve run the season before, yet you’ve spent up to a year avoiding doing so! So, here’s a radical proposal-if you really want to run a fast half mile in 1.44 or better, start running very fast 600 metres or similar every ten days throughout the year. Ideally you should be aiming to run them in 75 seconds or better. Otherwise, how can you expect to turn up for an international meet 800 metres and run relaxed through 600 metres in 78 seconds and maintain that pace if you haven’t been practicing it throughout the year; get your body accustomed to how it feels allowing it to make the key physiological adaptations. So, use pacers and aim to run two or three in training at around 75 seconds; come race day you’re more likely to be able to flow through the 600 metres mark in 78 seconds with a speed reserve for the last quarter of the race. An alternative good session which we used to do was a 600 metres (78 seconds); 500 metres (63 secs); 400 metres (48 secs); 300 metres (34 secs); and a 200 metres (22 secs) with a good recovery. Don’t shy away from these sessions. By incorporating this regime into your training programme you will steal a march on your rivals.

- Bread ‘n Butter Half Mile Sessions

To run a great half mile you also need to run bread ‘n butter half mile sessions; run 5 x 300 metres with a rolling start with a one minute walk 100 metres recovery, kicking off with 36 seconds. Or, 8 x 300 metres with a 3 minutes recovery starting with 37 seconds and try to hold the pace for as long as possible. 5 x 500 metres in 65 seconds with a 5 minute recovery is good as is 2 x 4 x 200 metres (30 seconds recovery) kicking off at 24 seconds. Clocks are excellent for gradually bringing on a jaded tiredness as you try to maintain speed endurance and quality-100-150-100 and 150-200-150 clocks (up and down in 10 metres) with a jog back 90 seconds recovery are excellent-they’re niggly little sessions. There’s no harm in occasionally joining the milers pack for one of the more traditional middle distance sessions-8 x 400s (1 minute recovery) or 4 x 600s (4 minutes rest) but they should be just that-occasional.

- Quarter Miling

To run a fast half mile you need to be able to run a great quarter too. Sometimes I ask good half-milers what they can run for 400 metres; they will reply vaguely, Oh! I’ve run sub 48 seconds-but when you ask what they can run right here, right now, there’s a world of difference. So don’t kid yourself. To run fast over a quarter you need to incorporate regular quarter-mile sessions e.g. 3 x 300 metres flat out in around 34 seconds. Or, 8 x 100 metres rolling with an easy 5 minutes’ walk around the track recovery.

- Resilience and Racing

Training and competition requires resilience. A few people have this quality in spades-a rod of steel running through them. I’ve trained with former world 5000 metres record-holder, David Moorcroft, and regularly with Adrian Weatherhead; with them it’s something inherent. I’ve seen it too with many of the distance runners-the iron men of the iron ground, who churn up the laps in cross country running. But the rest of us aren’t quite so hardy. However, you can help to overcome this with clever stratagems. Remember that dream. Use it to motivate yourself. Ask yourself what your success would mean to others who help you-your family, your friends? Develop mantras for when the going gets hard-First to the tape, First to the tape or Never give in, Never give in.

As usual, Kipling is good:

If

‘…If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son…

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on!’

If you’re doing a hard reps session don’t think too far ahead; leave the next run until towards the end of the recovery period-often people throw in the towel far too early. Take one run at a time. And when it becomes painful either embrace the pain-associate with it or alternatively disassociate from it by deploying some distraction techniques.

Some of you will recall the great BBC athletics commentator for forty years, David Coleman, and how he brought to life David Hemery’s stunning Olympic run in Mexico, 1968 or Ian Stewart’s magnificent 5000 metres win at the 1970 Commonwealth Games. On occasion,when I struggled through a tough training session wanting to give up, come these last few repetitions, in my imagination I could hear Coleman’s voice in my mind’s-eye ‘…and it’s Hemery (Hoffmann) gambling on everything…he’s really flying down the back straight…Hemery (Hoffmann) leads…it’s Hemery (Hoffmann) Great Britain…it’s Hemery (Hoffmann) Great Britain…and Hemery (Hoffmann) takes the gold…he killed the rest…he paralysed them…Hemery (Hoffmann) won that from start to finish…’ And before I knew it, the session was over and I’d run as best as I could and got through another tough work-out. I guess it’s called motivation-self-motivation. Find it where you can.

Ecclesiastes 9:11 says ‘…I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all…’ so grab the opportunity in any race-be brave-show some chutzpah-seize the day; sometimes a smarter, more confident athlete can beat a better one-Matt Centrowitz ran a great race at the Rio Olympics in the 1500 metres. Races are nerve wracking so get used to handling them well by racing often-race under distance events such as 400 metres where there is slightly less pressure.

Rest up before you race, making sure you taper your training. The people who knew best how to bring athletes to their peak were the old Pro schools in Scotland training athletes for the famous century old Powderhall Sprint. Money talks. And some of those schools stood to make significant monies from the bookies. Come the race, if you can and have the confidence to do so, aim to distribute your energy wisely in half-mile races. Run the shortest distance and run even pace.

My final thought on racing is ensure you’re thoroughly warmed up having blown the carbon out of the engine! Too many athletes don’t warm up sufficiently; and when the race kicks off it comes as quite a shock to the system and naturally, negatively impacts mentally on their confidence too. How often have you found in training that it’s the second or third repetition that’s the easiest? The first few runs feel hard because of the systemic shock; the latter runs are hard because you’re beginning to tire. Whereas, on the intermediate repetitions you glide along, often effortlessly, because your body is completely warmed up; make sure you go to the line having struck the optimal balance so that you’re ready to race from the bang of the gun.

Whether, you’re an international athlete, an aspiring one, or a master runner, adopt the above and you’ll fly a half mile. Good luck with your adventures and seize the day.

A Hypothetical 800 metres Training ‘Week’

Day 1 3 x 600 metres flat out (15- 20 minutes recovery)

Day 2 60-90 minutes steady run

Day 3 5 x 300 metres (walk 100 metres recovery)

Day 4 2 x 4 x 30 metres (3 minutes recovery; 15 minutes between sets) followed by strength-work

Day 5 8 x 100 metres fast (walk 300 metres recovery)

Day 6 Parkrun 5k

Day 7 8 x 300 metres (3 minutes recovery)

Day 8 6 x 50 metres flat out (4 minutes recovery) followed by strength-work

*Peter Hoffmann partnered Steve Ovett and Sebastian Coe as one of Great Britain’s three 800 metres athletes at the 1978 European Championships and was also part of the 1976 Olympic 4 x 400 metres squad at Montreal. He is the author of several books including A Life In A Day In A Year-A Postcard From Meadowbank which follows a ‘year’ in the life of an athlete. He is available for athletics advice on 400 and 800 metres running.*