..

One of only four British Soldiers, and the only Scot, buried in Nijmegen Cemetery. Harold Servant is commemorated with the stone on the right of those above.

Harold Servant was a young man who had been a Clydesdale Harriers for only a few years when he enlisted. He had nevertheless been elected to the club committee where he rubbed shoulders with such as Willie Maley of the Celtic FC and dealt with the day to day running of the club as Assistant Secretary with Thomas Barrie Erskine. He had been elected in 1912/13 to the post of Joint Secretary and that year was also District Convener. The club had for organisational purposes divided itself into several Districts and each District had its own Committee and structure. To be District Convener was to hold a responsible post. The following year he was again Joint Secretary with Tom Erskine but had been moved to be Convener of the Handicapping Committee. A promotion from the District Convener since almost all races other than Championships were handicaps that were organised according to strict rules. He seems to have been a man groomed for future senior administrative office.

What little we have of his running ability would seem to indicate that it was not his real strength. In the club 880 yards handicap in August 1914 he had a handicap of 120 yards and was still unplaced. It should be remembered of course that the club was very strong at that time with several Scottish international runners, and that he was only 19 when the war broke out.

The story of his Army career is encapsulated in the following paragraph:

“Mr William Gardiner, president of Clydesdale Harriers has been apprised of the death at the British Red Cross Hospital, Nymegen, Holland on January 3rd, 1919 on his way home after 20 months as a prisoner of war at Langensalza, Germany and 4½ years service of Pte Harold D Servant, Royal Marine Light Infantry. This is a very serious blow to Clydesdale Harriers which has given so many of its members to our country’s cause. Harold Servant was, along with the late Capt T Barrie Erskine, MC, hon joint secretary of the club and was a keen and enthusiastic supporter of everything that was for the betterment of athletics. The club also mourn the loss of their hon assistant treasurer Lieut J Marshall working on the Salonika front and now presumed killed.”

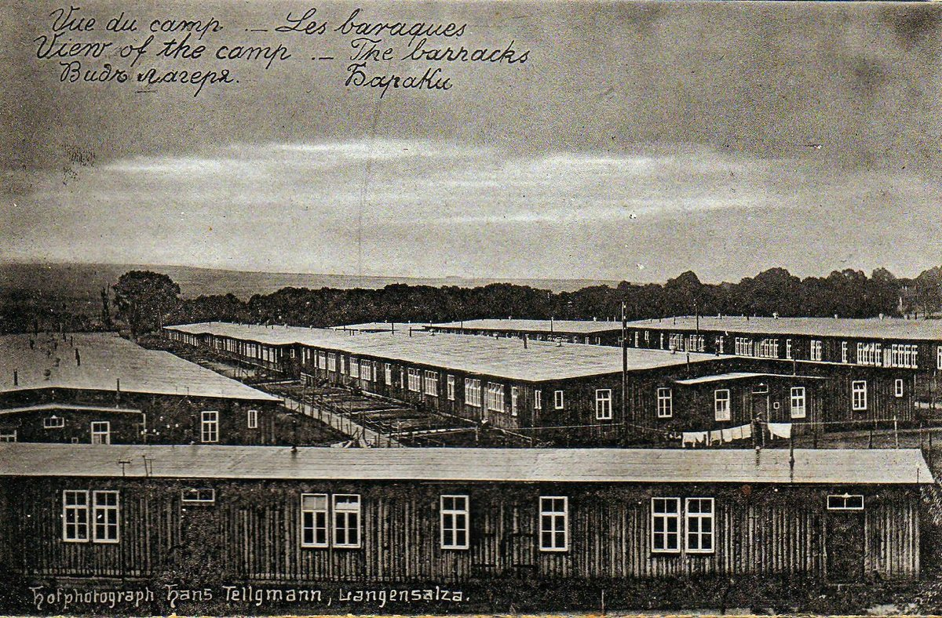

Langensalza Camp had a fairly large population of prisoners of all nationalities. British prisoners were in the middle hut which is described here.

There were confined in this building 575 prisoners of war, Russian and British and French, of whom 61 are British, of the 61 British 3 were Sergeants, 27 Corporals and 30 Privates.

The beds were of the bunk type, arranged transversely across the tent division. The British were lodged in the central tent division and a few on the side division. The bunks were built in, of wood, the lower tier a short distance above the floor, the upper tier 4 feet above this. The bedding was of the straw-mattress type. The arrangement is faulty in the sense that the central barrack lacks both light and good ventilation.

The latrines for this division were of the iron receptacle semi-tubular type, open, and flushed into an underground drainage system. The surroundings, floors, etc. were poorly cared for and could. be cleaner than they were at the time of our inspection.

That’s a description of the actual camp and accommodation but more importantly, what were the conditions there that Harold had to endure for 20 months?

*

We have reports and descriptions of life there from other prisoners who survived. One such account is below the photograph.

Langensalza Camp

“Feldwebel Rost was especially hard and brutal in his treatment of prisoners. In July 1918 I witnessed the following incident.

The prisoners were on parade, and many of them, being cripples, had difficulty in moving out of the huts. Rost rushed into the barrack, and, without giving the maimed men the time to get out, he caught hold of a private who was very badly wounded in the abdomen, and had to walk with a slick, by the back of the neck and threw him violently down the steps. This is only one of the many instances of his bullying; he was also responsible for sending many men to the salt mines who were quite unfit to go there. The full name of this man is Feldwebel Rost, 6th Company; he lived at Jena, and his occupation is students’ servant.

On 27 November, at 1 p.m. we had just finished our dinner in the British Help Committee hut, and we heard an unusual bugle-call. Three of us went out. The hut was situated about 15 yards from the sentry box at the gate, which led to the tailors’ and bootmakers’ shops, and was about 30 yards from the theatre. The theatre contained dressing rooms, which had been put up by the prisoners, one for each nationality. At this time these dressing-rooms were being pulled down and prisoners used the woodwork for fuel. When I came out from the Help Committee hut I saw that the theatre was surrounded by a group of about 20 or 30 of different nationalities. There was no disturbance or riot of any kind, and the prisoners were only going in and out of the theatre carrying pieces of wood from their respective dressing rooms.

After the bugle call about 30 soldiers, with an under-officer in charge, named Krause, came out of the Landsturm barrack, which was situated some 40 yards from the Help Committee hut and about 40 yards from the theatre. The soldiers surrounded the British Help Committee hut and the theatre in extended order. I was standing near the gate, about 6 yards away from the under-officer. He said to me in broken English, “What are you making trouble for?” I replied “There is no trouble at all.” And I asked him why the soldiers were surrounding the theatre and our hut, but he made no answer. I remained where I was between the committee hut and the gate, and after an interval of three minutes I heard him give the order to fire. I am quite certain that he gave the order to fire, for I had often heard it given before when at the front. There must have been 15 to 20 prisoners standing outside the hut, and I should say about 30 others round the theatre. When the order to fire was given, I tried to get into the committee hut, but the door was so crowded by others endeavouring to do the same that I could not get in. At least 15 shots were fired in the direction of the committee hut, with the result that Private Tucker, Worcester Regiment, who was standing 8 or 9 yards from me, was killed instantly, receiving three bullets; Private Morey, East Yorks, standing 10 yards from the hut, was also killed, being shot in the head. Corporal Elrod, 6th Northumberland Fusiliers, must have been 60 yards away from the theatre, near the football ground; he was hit by a bullet in the spine, from the effects of which he died eight hours afterwards.

Two of the men who were trying to get through the door of the hut were wounded – Private F. Johnson, 4th Bedfordshire Regiment, and Private Haig, West Yorks – and there were three bullet marks in the committee hut door. Private Johnson told me that when the firing commenced he threw himself flat on the ground, and that when he tried to crawl into the hut he was fired at again by the soldiers.

When the firing was over, the under-officer (Krause) Approached Private Haig, who was lying on the ground, and said to him, “Why did you not get out of the way when I told you to go?” Haig said, in reply, that Krause had never told him to do so.

Shortly afterwards Company Sergeant-major Thomas, Somerset Light Infantry, Sergeant. Major R. S. Finch, Northumberland Fusiliers, and I, went to the kommandantur, where we found Captain von Marschall. We asked him if he was responsible for the firing which had taken place. He said no, because he was away from the camp at the time. He was asked from whom the prisoners could obtain satisfaction, and he referred us to the officer of justice, Feldwebel Lieutenant. This officer typed down my evidence, which was interpreted by Dolmetscher Weither. Some days later I gave the same evidence to a judge, a civilian, who examined me, and again a few days after a major from the War Office took my evidence. I asked this officer to forward it to England, and he said that the evidence would go there through one of the ambassadors. The under-officer Krause gave his evidence at the same time, and he denied that he had ever given the order to fire, but I am quite certain that I heard him give this order. About a week after the occurrence I saw Krause in Langensalza Camp at liberty and in civilian clothes. I heard that he had obtained his discharge and was living in lodgings in Langensalza.”

*

Harold was one of only five British soldiers buried at Nijmegen Cemetery where his date of death is given as 3rd January, 1919 and his regiment as the Royal Marine Light Infantry (Number Ch/485/S)

From the Commonwealth War Graves website:

Private SERVANT, HAROLD DAWSON

Service Number CH/458/S

Died 03/01/1919

Aged 25

1st R.M. Bn. R.N. Div.

Royal Marine Light Infantry Son of William and Agnes Servant, of 549, Crow Rd., Jordanhill, Glasgow.